Sports psychiatry is an emerging focus within general psychiatry, and training within this field can be of benefit in at least two ways. First, it can provide deeper understanding of the context in which an individual or team athlete exists, which can then be harnessed to achieve greater rapport and treatment success. Second, a core takeaway—at least in the opinion of the authors—is that this field reframes the focus of the psychiatric treatment being provided not just on the reduction of symptoms but on enhancing individual patients’ ability to overcome challenges while in pursuit of their dreams.

The founder of sports psychiatry, J.H. Massimino, once declared: “The primary role of the sports psychiatrist must be a clinical one: to prevent, diagnose, and treat the psychiatrically related medical issues confronting the athlete.” On a certain level, this is no different from the role of all psychiatrists, as we must gain an understanding of the preferences and goals of each patient we see and then apply our professional expertise to the task of reducing the negative impact of troublesome mental health symptoms. Understanding the unique environments in which athletes spend considerable time can enhance the ability of a physician to treat that individual, in the same way that an understanding of a patient’s sociocultural background can be crucial to psychiatric care.

It is worthwhile to note that sports psychiatry differs from sports psychology, although the two fields have some overlap. While sport psychologists primarily focus on enhancing an athlete’s performance through mental skills training and psychotherapy interventions, sports psychiatrists focus additionally on reduction of the negative impacts that can arise from primary diagnoses as well as iatrogenic effects of treatments, including those from medications. The goal of a sports psychiatrist is to treat the primary symptoms successfully while minimizing overall side effects from treatment—in particular, side effects that can impact athletic performance. However, collaboration between these disciplines is essential to optimize an athlete’s performance and well-being. Through the growth of this subspecialty, athletes will receive expert care with special attention given to the potential side effects that psychiatric medications can have on performance in sport.

The Impact of Athleticism on Mental Health

A 23-year-old female who plays professional basketball presented with concerns about inattention and difficulty with concentration. She had been told by her athletic trainer that she should be evaluated for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Upon evaluation, she described a long history of difficulty in school, starting in elementary school. She often got in trouble for getting up during class and not turning in her homework on time.

Throughout high school and college, she continued to struggle with concentrating and did not get good grades due to an inability to study for prolonged periods of time. When she started her professional basketball career, she started noticing that she would zone out while the coach was talking to her or addressing the group. At that time, she also struggled to get to practice on time and would forget some of her gear on game day.

Athletics can impact an individual’s mental health in myriad ways, and it is crucial to recognize that not all athletes face the same specific challenges. Swimmers and triathletes, for example, can face different stressors than team athletes, such as football and basketball players. Similarly, in young athletes, anxiety and depression have been found to be more common in those who play individual sports than those who play team sports, possibly because there may be some protective factors in team sports, such as social interactions, promoting fun and stress relief, while athletes in individual sports may experience internal attribution and even isolation after failure (Pluhar, et al., 2019).

Youth athletes can face different obstacles than elite college or professional athletes. It is important, both for developing rapport and for increasing the likelihood of treatment success, to recognize these differences and be able to see the individual under your care in the specific context of their sport. It is equally important to recognize that the sport itself is simply the context; the person in front of you is the unique individual living and performing in that context. There are different data points for different sports, but research suggests that mental health disorders may occur in one out of three elite athletes (Reardon, et al., 2019).

While there are psychological factors that affect mental health in athletes, conversely there are many physiological benefits that exercise has on mental health. Studies have shown that aerobic exercises, such as running, swimming, and cycling, can reduce anxiety and depression symptoms through effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Despite these benefits, exercise must be balanced with appropriate recovery, or overtraining can occur. As with much of life, too much of a good thing can be a bad thing.

The six pillars of lifestyle medicine are physical activity, nutrition, stress management, restorative sleep, social connection, and avoidance of risky substances (American College of Lifestyle Medicine, 2023). While we may assume that athletes are already doing all the lifestyle interventions that we might want to apply to mental health both proactively and reactively, this may not always be the case. An athlete may have a strong physical activity pillar, for example, but that does not necessarily mean they are adequately addressing the other five pillars. An athlete may even try to compensate for other crumbling pillars through increased exercise, which can be problematic. If health becomes overly dependent on one pillar, then the health of that individual is likely to be strained.

Common Psychiatric Diagnoses in Athletes

During the initial assessment, the patient scored high on the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1), indicating a likely diagnosis of ADHD. From subjective and objective data, she was diagnosed with ADHD, predominantly inattentive type.

As with any subspecialty, sports psychiatry has its common diagnoses. Here are conditions that are frequently observed in athletes:

Sleep disruption: Disrupted sleep is a common issue in athletes just as it is in the general population. Specific considerations to keep in mind if an athlete is presenting with sleep issues are the impact of early-morning (or late-evening) practices or competitions, travel for competitions (which may be across multiple times zones, especially at the elite level), anxiety about performance, soreness or injuries resulting from play, or simply the intensive amount of time some athletes put into training, which may limit the hours they have in the day to complete other necessary tasks (work, school, social connection, etc.). It is also important to consider the impact that traveling through different time zones for competition may have on sleep as well. Being an athlete does not provide immunity against sleep disorders, and screening for common disorders such as sleep apnea or insomnia can provide the opportunity to diagnose and treat this area of human health that is so often overlooked but can have a tremendous impact on the mental health, overall health, and performance of an athlete.

The primary treatment for insomnia is cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), which targets one’s cognitions and behaviors that interfere with sleep (Creado & Advani, 2021). Melatonin is the most widely studied supplement that aids in sleep in the general population, yet research is limited in athletes specifically. It may also have additional benefits in athletes through its suggested anti-inflammatory effects, and is likely best used as one tool in a comprehensive approach to combat impact of disrupted sleep when athletes travel across time zones (Creado & Advani, 2021).

Of prescribed medications, trazodone and z-drugs are most commonly used by sports psychiatrists. There is minimal data on the impact of these medications on athletic performance, though one small study of zaleplon suggested performance impairment the morning after use (Reardon & Creado, 2016).

Disordered eating: Eating disorders are more common in athletes than in the general population, although this may vary depending on the type of athlete. Risk factors include sports that emphasize weight or appearance. Related to eating habits, another important concept to understand for the sports psychiatrist is relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S)—a term that is used to describe the disruption caused to various body systems that results from chronic low energy availability in an athlete. In many ways, RED-S is a broader application of the term “female athlete triad,” which was used to describe chronic low energy availability in a female athlete with resultant disruption of menstruation and bone mineral density. RED-S shifts the focus away from just females with these specific disruptions and highlights that chronic low energy availability has a negative impact on the health (and performance) of male and female athletes.

Anxiety: The prevalence of anxiety disorders in athletes is approximately 9% (Reardon, et al., 2024). An athlete can experience normal competition, or performance-induced hyperarousal, or struggle to manage competitive performance anxiety or an anxiety disorder. The source of the anxiety, its duration, and its impact on functioning help to distinguish these symptoms. Posttraumatic stress can stem from the same events that nonathletes experience, but it can be useful to know that emotional trauma may be increased in individuals with a stronger athletic identity. This may be due to the injury impacting their ability to play or compete, which in turns threatens their identity.

For mild to moderate anxiety, psychotherapy is often recommended as the first-line treatment (Reardon, et al., 2024). When symptoms are in a more moderate to severe range, medications should be recommended. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the first-choice medication in athletes, specifically escitalopram, sertraline, and fluoxetine (Reardon, et al., 2024).

ADHD: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is a common brain-developmental disorder that exhibits persistent patterns of age-inappropriate inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity, causing dysfunction in multiple settings and interpersonal relationships starting before age 12. The prevalence of ADHD in student athletes and elite athletes may be 7% to 8% (Han, et al., 2019). The lack of focus and concentration can negatively impact an athlete’s performance. Athletes with ADHD may exhibit signs such as not paying attention while their coach is talking to them, forgetting about practice, losing their gear, or showing up late to competitions. It is important to assess, diagnosis, and treat athletes in a timely manner.

It is important not only to provide psychoeducation with regard to stimulant treatment for athletes, but also to review any prohibited substances as determined by their sport’s governing body, ensuring that the psychiatrist is prescribing in accordance with the body’s requirements. It is also important to point out that physical activity and sports themselves can improve ADHD symptoms by providing a physical outlet for intense emotions and stress.

The treatment of choice remains non-stimulants, such as atomoxetine. Stimulants should be used with caution due to the possible adverse effects. It is important to note that there are potential side effects in adult athletes with ADHD taking stimulants, including lack of creativity, lack of spontaneity, palpitations, sweating, and irritability. Most severely, sudden cardiac death has been observed in some athletes on treatment with stimulants, which has been attributed to a lower threshold for cardiac arrhythmias.

Through the activation of dopamine and noradrenergic systems, it results in improved attention and concentration. Both child and adult athletes with ADHD experienced better outcomes in attention when compared with athletes treated with non-stimulant medications (Han, et al., 2019). Because stimulants have been placed on the prohibited substance list by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), a therapeutic use exemption (TUE) must be obtained to receive treatment for ADHD with this class of medication. However, if medications are clinically necessary for an elite athlete with ADHD, non-stimulant medications should be considered (Han, et al., 2019).

Depression: Depression broadly impacts athletes at similar rates to the general population, although there may be variation across levels and sports, and it merits the same level of attention that it garners in nonathletes. Prevalence rates of depression in college athletes were found to range from 15.6% to 25.6% (Edwards, 2021). Sport considerations may include which medication is the best starting point to minimize any impact on athletic performance. An important consideration when assessing an athlete with depressive symptoms, however, is their training load, including whether they are allowing adequate time for recovery from that training. While not fully defined, overtraining generally describes a situation in which training exceeds recovery and results in prolonged performance decrease and psychological or neuroendocrinological symptoms, including fatigue, sleep disruption, change in appetite, weight loss, reduced ability to concentrate, and reduced athletic performance (Reardon, et al., 2019). Many of these symptoms overlap with depression, but for an athlete who is experiencing overtraining, the best treatment may be reduction in training to allow for recovery, as opposed to therapy or medications. Missing this may lead to a prolonged recovery course.

There is limited data regarding antidepressants’ efficacy and tolerability in this population; data is available only on two of the SSRIs: fluoxetine and paroxetine. Based on two small placebo-controlled trials, the first-line treatment for depression in athletes is fluoxetine. Paroxetine is not recommended, as preliminary data suggests that it might decrease performance in athletes. For athletes with depression, without comorbid anxiety, bupropion can be considered (Reardon, 2016).

Of note, WADA has placed bupropion on its monitoring list out of concern for potential performance-enhancing effects. Were it to be banned, this would certainly change its use by sports psychiatrists.

When compared with non-athletes, elite athletes exhibit reduced risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and suicide completion (Gill, et al., 2024). The review found that non-white race and male sex were associated with increased rates of suicide behavior within elite athletes. Although the overall risk is decreased in the athletic population, it is essential to focus on prevention of worsening mood disorders, such as depression, as well as adequate screening protocols in order to be able to intervene effectively.

Unique Considerations in the Treatment of Athletes

It was recommended that the patient begin medication with stimulant treatment to address her ADHD symptoms. Due to her participating in a professional sports league, a signed authorization to release information was obtained to discuss the diagnosis and recommendations with the athletic trainer. The athletic trainer then discussed the league’s requirements for therapeutic use exemptions for controlled substances, including stimulant medication for ADHD.

Sports psychiatry is its own subspecialty of psychiatry for the simple reason that it is imperative that special consideration be given when treating athletes. It is also essential to understand the ecosystem of sports, as athletes are surrounded by external pressures in expectations ranging from their agents to family members to teammates, as well as coaches, team owners and general managers. It may be helpful for a sports psychiatrist to explicitly define the different areas of influence on an individual athlete’s mental health; Purcell, et al. (2019) defined one such model. Having a framework such as this may decrease the likelihood that potentially significant factors get overlooked, and may reduce the chance of over-pathologizing the individual athlete.

A psychiatrist working with athletes at any level must give significant thought to potential medication side effects and how they may impact an athlete’s performance and their goals; it is then important to discuss these potential adverse effects, along with other risks and benefits, when discussing starting medication in an athlete. For example, propranolol is often used for managing performance anxiety; however, it can impair physical performance by decreasing heart rate and impacting endurance (conversely, in certain sports such as shooting, it can provide an advantage by reducing tremor, and in such sports may be banned in and potentially even out of competition). Other classes of psychiatric medications that merit scrutiny include antipsychotics, which can cause weight gain, and benzodiazepines, which can cause sedation (Reardon & Factor, 2010). All these medications have the potential to negatively affect an athlete’s performance and therefore impact their adherence to treatment.

Another essential consideration when treating elite athletes are the rules and regulations in their professional sports leagues and governing bodies. Each professional league has different prohibited substance lists and different steps for obtaining a TUE—governed by WADA—which are necessary for athletes who use medications that are otherwise banned in competitive sports. For example, athletes diagnosed with ADHD often require treatment with stimulants, which are a prohibited substance in most sports; in such cases, a TUE becomes essential for the athlete to receive necessary medical treatment.

Sports psychiatrists must consider these restrictions and the necessary steps for their athletes to receive approval for prescribed medications. In certain professional leagues, such approval must be given even before the psychiatrist can send a prescription to the pharmacy. Failure to comply with these policies may result in athletes being disqualified from their sports, which could significantly disrupt the therapeutic alliance.

The Role of a Sports Psychiatrist

After submitting the appropriate paperwork to the league, the player was approved for ADHD treatment, and a prescription was sent in. After starting Concerta 18mg daily, the patient noticed a rapid improvement in her ability to concentrate during practice as well as manage her time and tasks better.

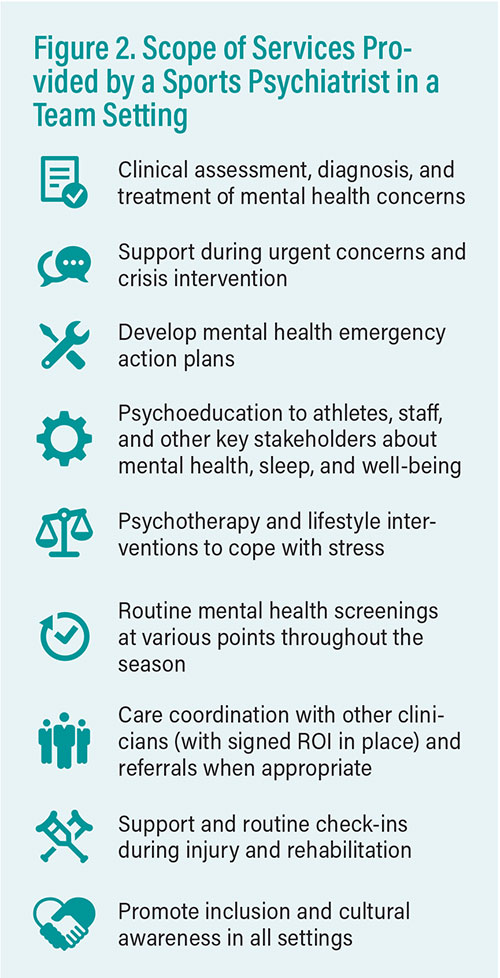

Sports psychiatrists play a crucial role in supporting the mental health and well-being of athletes. They not only provide individual services to athletes but also can also work with sports organizations and teams, providing clinical and educational services. In an individual treatment relationship, the sports psychiatrist is responsible for assessing, diagnosing, and treating the athlete using psychotherapy, medication intervention, or both.

When working with a sports team or organization, a sports psychiatrist often provides several services. First and foremost, the psychiatrist provides education to key stakeholders on their role within the organization, including owners, general managers, athletic directors, and head coaches/managers (McDuff & Garvin, 2016). Services should include psychiatric assessment, diagnosis, and treatment, in addition to providing educational workshops and assisting with writing a mental health emergency action plan for the team. On competition days, the team psychiatrist may be responsible for meeting with players before or after the game to check in or practice different mindfulness skills to help them prepare for peak performance.

In a team environment, it is also the sports psychiatrist’s role to provide education to various departments—including security, media relations, and the front office—to clearly establish the difference between mental health emergencies and urgent concerns. From there, it is then important to develop a referral chart that provides information on how key stakeholders can connect players to the appropriate level of mental health care. Depending on the needs of individual players and the organization, a sports psychiatrist can fill many roles.

Certification and Specialized Training

There have been several recent developments in sports psychiatry that show significant promise for the growth of the field—and its integration with sports medicine—within academic institutions. In 2023, the American Board of Sports and Performance Psychiatry (ABSPP) was founded to advance the field and maintain the highest standard for certification, education, and professional practice; the ABSPP provides three pathways toward certification, which are available to board-certified psychiatrists. Similarly, the International Society for Sports Psychiatry offers a Certificate of Additional Training in Sports Psychiatry, which is available to medical students, psychiatry residents and fellows, and board-certified psychiatrists, while the International Olympic Committee (IOC) offers the IOC Diploma in Mental Health in Elite Sport for physicians and other practitioners who work with athletes.

The field of sports psychiatry is certainly developing at a rapid pace, but more needs to be done to ensure certified and qualified psychiatric physicians are providing care to this subset of individuals. ■