Mental health service use declines when children reach 18 or older. Nationally representative administrative data show that for 16- and 17-year-olds, annual rates of inpatient, outpatient, and residential service use were 34 per 1,000, whereas rates for 18- to 19-year-olds were nearly half: 18 per 1,000 (

1). In a longitudinal study of children with bipolar disorder, Hower and colleagues (

2) noted a gradual decline in service use by persons ages 12–22 that was unrelated to illness severity or functional impairment. The decline in service use may differ according to service type. When controlling for young adult clinical profiles and demographic characteristics, Pottick and colleagues (

3) found a marked decline in receipt of individual office-based therapy for 18- to 21-year-olds compared with 16- to 17-year-olds. However, no differences were found between these age groups in receipt of psychotropic medications (

3). Observed decreases in service use coincide with an increase in the prevalence of mental disorders among adolescents ages 13–18 (

4). Low rates of service use continue for young adults ages 18–26 (

5,

6). Meanwhile, service use increases from childhood to adolescence. For example, Merikangas and colleagues (

7) found that young adolescents (ages 12–15) were more likely to use mental health services than children ages eight to 11, even when analyses controlled for mental health need. During adolescence, schools are a critical point of access for mental health services. Adolescents are more likely to receive mental health services in school than in a specialty mental health setting (

8); however, we have little information about how this use may change across adolescence. Typically, studies combine adolescents into one age group, masking potential age differences in mental health service use across adolescence. The objective of this study was to examine mental health service use by adolescents from ages 12 to 17, by service type (school-based, outpatient therapist or clinic, or overnight hospital stay). We hypothesized that, for all service types, use would decrease linearly from ages 12 to 17.

Methods

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) is an annual survey designed to estimate annual prevalence and correlates of substance use and mental health issues. It is nationally representative of the civilian, noninstitutionalized U.S. population ages 12 and older. The design comprises an independent multistage area probability sample for each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Approximately 68,000 interviews are completed annually; interviews are administered with audio computer-assisted self-interviewing in households. Respondents provide consent for participation after hearing a complete study description and receive $30 on completion. Detailed descriptions of the 2008–2012 NSDUH methods are available on the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Web site (

9). Procedures were approved by the RTI International Institutional Review Board (

9). We analyzed combined 2008–2012 NSDUH data from approximately 113,000 adolescents ages 12 to 17.

Adolescents were asked whether in the past 12 months they had received treatment or counseling services from a variety of providers or locations because of “problems with your behavior or emotions . . . not caused by alcohol or drugs.” Providers and locations reported in this study included those most commonly endorsed by adolescent respondents. Selected service types examined in this study included outpatient therapist or clinic, which included a private therapist, psychologist, psychiatrist, social worker, or counselor or an outpatient mental health clinic; school-based services, including from a school social worker, school psychologist, or school counselor or from a special school or program within a regular school for students with emotional or behavioral problems; or overnight hospital stay, including overnight stay or longer in any type of hospital. Service types reported by well under 1% of adolescent respondents—and therefore not covered in this report—included in-home counseling, therapeutic foster care, mental health treatment received in juvenile detention, and services received from a residential treatment center.

Using polynomial contrasts, we tested linear and quadratic patterns across ages 12–17 for each service type were tested. Rates of service use were averaged across the 2008–2012 NSDUH data at each age (in years). Before averaging age-level rates of service use across 2008–2012 NSDUH survey data, we investigated potential differences between age cohorts in service rates across survey years. Results indicated no consistent age-level patterns in access rate across survey years. In order to control for type I error inflation from multiple testing, a Bonferroni correction was applied (

10). Analyses used PROC Descript in SUDAAN, version 11.0, to account for NSDUH’s complex sample design. Sampling weights were used in order to yield population estimates for the 12–17 age group; because we combined five years of survey data, sampling weights were divided by the total number of survey years of data.

Results

Results (mean±SD) indicated that adolescents were most likely to receive school-based services (12.3%±.2%), followed by outpatient therapist or clinic services (10.1%±.1%). Adolescents were least likely to have reported an overnight hospital stay (1.8%±.1%).

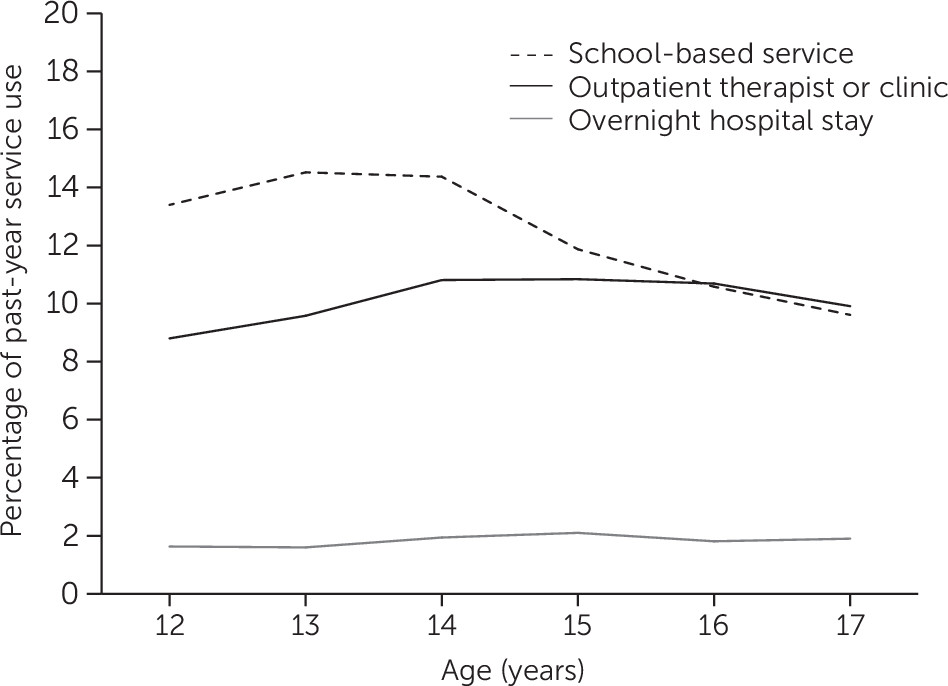

As

Figure 1 shows, the use of school-based (t=−4.7, df=900, p<.01) and outpatient therapist or clinic (t=−5.1, df=900, p<.01) services across ages 12–17 was characterized by a convex quadratic pattern (inverted U). By comparison, overnight hospital stay (t=2.1, df=900, p<.01) services showed a linear pattern (increasing from age 12 to 14 and almost flat from age 15 to 17). For all service types, use increased from age 12 to14 and then either declined (therapist or mental health clinic and school-based services) or remained level (overnight hospital stay) from age 15 to 17. The decline was particularly apparent for school-based services, where service use decreased from 14.5%±.4% at age 13 to 9.6%±.3% at age 17.

Discussion

Previous research has demonstrated a decline in mental health service use in young adulthood (

1) and an increase from childhood to adolescence (

7). This study extended that work by examining age-related patterns of service use across adolescence. Results depict increasing use from age 12 to 14 and then declining or leveling mental health service use beginning in midadolescence (at age 14 or 15). In particular, school-based service use declined markedly for ages 14–17. A relatively smaller, but still significant, decline over a similar age span was seen for services from outpatient therapists and clinics.

Schools have long been noted to be the leading and often de facto provider of children’s mental health services (

4,

8). Schools play a critical role in providing and coordinating children’s mental health care. Available school resources can impact children’s use of school-based mental health services (

11). One recent study found that adolescents are more likely to use school-base mental health services when attending a school with more early identification and referral resources. Between ages 14 and 15, most adolescents transition from middle school to high school. Could a decline in mental health service use in late adolescence be the result of insufficient resources for mental health treatment at the high school level or a function of state budget cuts associated with the economic downturn? These questions cannot be answered with the results of this study but indicate worthwhile avenues for future research designed to understand this decline in school-based mental health service use and its root cause.

One limitation of our study is that service use was not considered in light of mental health need. NSDUH does not include a comprehensive measure of adolescent mental health status. However, several studies have found that the prevalence of mental disorders gradually increases throughout adolescence (

12). Our findings suggest that rates of service use decline as adolescent mental health needs increase. Future research is needed to better understand this decline, factors related to decreased use of mental health services, and strategies to increase service access throughout the adolescent years. A second limitation is that service use was limited to adolescent self-report; adolescents, particularly younger adolescents, may not be accurate reporters. Reporting accuracy differences by age could have biased study results. Fortunately, prior research shows relatively high agreement between adolescent and parent reports of the receipt of any mental health treatment (

4,

8). Finally, this study focused on only four types of treatment and did not examine trends in some less common, but still important, service sectors (including residential treatment, child welfare, and juvenile detention). Non–household-based samples or studies of vulnerable populations would be particularly well suited for examining patterns in service use by age in these less commonly used sectors.