Many people with depression do not fully respond to their first treatment, typically an antidepressant or psychotherapy. Among the options for these patients is to initiate combination therapy—that is, antidepressant plus psychotherapy. A long-standing clinical question has been whether the order of treatments is important. Is starting a patient on an antidepressant and then adding psychotherapy more, or less, effective than the other way around?

A study

published last month in

AJP in Advance suggests that the sequence in which these two types of treatments are applied does not affect the chance of the patient achieving remission.

These findings arise from the second phase of a study known as Predictors of Remission in Depression to Individual and Combined Treatments (PReDICT). The aim of the study is to identify characteristics that might help predict whether a patient is more likely to respond to medication or psychotherapy. (The first results,

published in the

American Journal of Psychiatry in 2017, showed that patients’ preference for a type of therapy did not affect their chance at getting better, but having a preferred treatment improved adherence.)

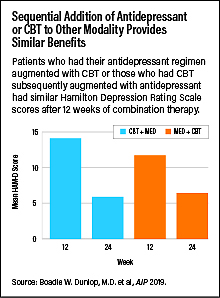

PReDICT enrolled 344 adults who had depression without psychosis or suicidal thoughts to receive 12 weeks of either cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or the antidepressants escitalopram or duloxetine. Patients who did not achieve remission of their depression after 12 weeks (defined as a score of 7 or lower on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale) could enroll in the second phase, which also had a length of 12 weeks. In this phase, the patients receiving CBT began taking adjunctive escitalopram (the CBT-first group), while patients taking escitalopram or duloxetine were given 16 CBT sessions (the medication-first group).

By the end of the second phase, 76 percent of participants in each group showed symptom improvement (28 out of 37 in the CBT-first group and 57 out of 75 in the medication-first group). About 65 percent of the CBT-first participants achieved remission (24/37) as did 60 percent of the medication-first group (45/75).

The odds of achieving remission were higher for patients who had shown at least some improvement in the first phase of the study. In patients who did not respond to CBT or medication alone, 40 percent achieved remission from combination therapy.

After phase 2, the investigators followed up with the participants for an additional 18 months and found that approximately 20 percent had a recurrence of depressive systems, with no significant difference between the two groups.

“The take-home message of this study is that for your typical outpatient, sequential treatment does work, and the order doesn’t matter,” said lead investigator Boadie Dunlop, M.D., director of the Mood and Anxiety Disorder Program at Emory University.

Dunlop added that in addition to alleviating concerns about which treatment should come first, he said he hoped that these results may convince psychiatrists about the value of augmenting existing treatments. “We should all keep an open mind and not default to adding more medicine or more intensive CBT if we don’t see results with the initial treatment.”

Dunlop cautioned that these findings may not apply to everyone; as noted above, depressed individuals with psychosis or suicidal ideation—conditions that may require inpatient hospitalization—were excluded from the study. Also, as is common in clinical trials, all the participants had depression as their primary psychiatric diagnosis.

“In real-world clinics, you do frequently see patients whose depression is secondary to another psychiatric condition like anxiety or trauma, and that may affect how they respond to treatments,” he said.

PReDICT was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Fuqua Family Foundations. Forest Laboratories and Eli Lilly donated the escitalopram and duloxetine used in the study. ■