Subjects

The total study group comprised 582 adult subjects in a study of genetic and environmental factors in vulnerability to alcoholism in three large and interrelated multigenerational pedigrees. We used the genealogical information to address the extent to which this family-derived study group is genetically representative of the tribe. The links between the three large pedigrees were identified, and the fraction of genes shared by common descent was calculated for all 169,071 pairs of the 582 participants. A randomly drawn pair of individuals shared only 1.2% of their genes by descent, equivalent to a degree of relationship that is between second cousins once removed and third cousins. This indicates that most pairs of individuals have a low degree of relationship. The average degree of relationship for the whole tribe has not been measured, but the average sharing by descent of 1.2% is compatible with the tribal population's size and history.

All subjects were required to be 21 years of age or older and to be eligible for enrollment in the Southwestern tribe (≥¼ tribal ancestry); all 582 subjects were enrolled tribal members. Because of the high prevalence of alcoholism in this population, there was no need to ascertain subjects through alcoholic probands. Therefore, the subjects were selected on the basis of pedigree structure and accessibility only and without knowledge of or reference to their clinical histories or the clinical histories of relatives. Detailed genetic, demographic, and social data were collected, allowing systematic description of the representativeness of the study group and comparisons to the larger population of the tribe, best estimates for which were derived by using U.S. census data. A more detailed description of the study population and the Southwestern tribe is provided elsewhere (

12).

Data on sociodemographic characteristics and psychiatric disorders were collected from all 582 subjects over a 4-year period (1991–1995). Although the research was designed initially as a genetics study, the investigators recognized that environmental factors could also influence outcomes. Therefore, the PTSD section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (

13) and the Traumatic Events Booklet (

14) were introduced midway through the study and applied consecutively to the final 247 participating subjects (117 men and 130 women). No additional inclusion or exclusion criteria or other selection bias were applied to this subgroup. All 582 participants were recruited in accordance with the study protocol.

Community support was instrumental in attaining a level of completeness that would have otherwise been unlikely. The study participants were recruited by local interviewers who were themselves members of the Southwestern tribe. Focus groups consisting of tribal staff and community members also assisted in the review of testing instruments, participant recruitment, and data collection. Considerable emphasis was placed on developing rapport with potential subjects. The participation rate was 93.7% of the eligible persons contacted. After complete description of the study, all subjects gave written informed consent under a human research protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the tribal council. Each subject received a stipend of $40 for participation.

Clinical Measures

DSM-III-R diagnoses were made by using a modified version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L), following operationally defined criteria, and using the instructions of Spitzer, Endicott, and Robins (

15,

16). The validity of the SADS-L has been well established in population and clinical studies (

17), and the SADS-L has been found to be reliable when administered by clinicians experienced in psychiatric assessment of American Indians (

18–

20). The diagnosis of PTSD was based on the PTSD component of the SCID (

13).

Both the SADS-L interview and SCID PTSD component were administered by a psychologist (R.W.R.) with extensive experience in working with American Indian people. The written SADS-L semistructured clinical interview was blindly rated for DSM-III-R lifetime and current diagnoses for all disorders except PTSD, yielding acceptable rates of agreement between two independent blind raters—a clinical psychologist (B.C.) and a clinical social worker (kappa coefficients ranged from 0.63 to 0.96). The SCID PTSD component was also blindly rated, resulting in a kappa coefficient for PTSD of 1.00, attributed largely to the highly structured composition of the SCID, from which PTSD was diagnosed. Only after the psychiatric interviews were evaluated blindly by independent raters was a consensus conference held to resolve diagnostic differences among the interviewer and blind raters and to assign final diagnoses.

Provisions were made to limit diagnostic errors due to culture-specific phenomena. For example, depression is overdiagnosed in some American Indian societies in which it is normative to mourn for the death of secondary relatives for more than 3 months (

21,

22). Schizophrenia can also be overdiagnosed in American Indian populations (

23) when culture-specific hallucinatory experiences during religious ceremonies or mourning are perceived as psychosis (

24,

25). In addition, high base rates of unemployment and lack of transportation can lead to overdiagnosis of antisocial personality and other disorders. Thus, the participants were questioned in detail about the specific circumstances that may have contributed to their unemployment.

Psychiatric disorders were evaluated typologically for lifetime (ever) and point (current) prevalences as defined by Spitzer et al. (

15). To facilitate comparative analysis, DSM-III-R diagnoses were grouped into the following six categories:

Mood disorders: bipolar disorder (296.4x, 296.5x, 296.6x), bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (296.70), major depression (296.2x, 296.3x), dysthymia (300.40), depressive disorder not otherwise specified (311.00).

Alcohol disorders: alcohol dependence (303.90), alcohol abuse (305.00).

Antisocial personality disorder (301.70).

Anxiety disorders: anxiety disorder not otherwise specified (300.00), generalized anxiety disorder (300.02), obsessive-compulsive disorder (300.30), panic disorder without agoraphobia (300.01), phobia (300.22, 300.23, 300.29).

Drug disorders: drug dependence (304.00–304.60), drug abuse (305.20–305.90).

Posttraumatic stress disorder (309.89).

To test for the specific relationship between episodes of trauma and PTSD, PTSD was analyzed independently from other anxiety-related diagnoses.

The Traumatic Events Booklet (

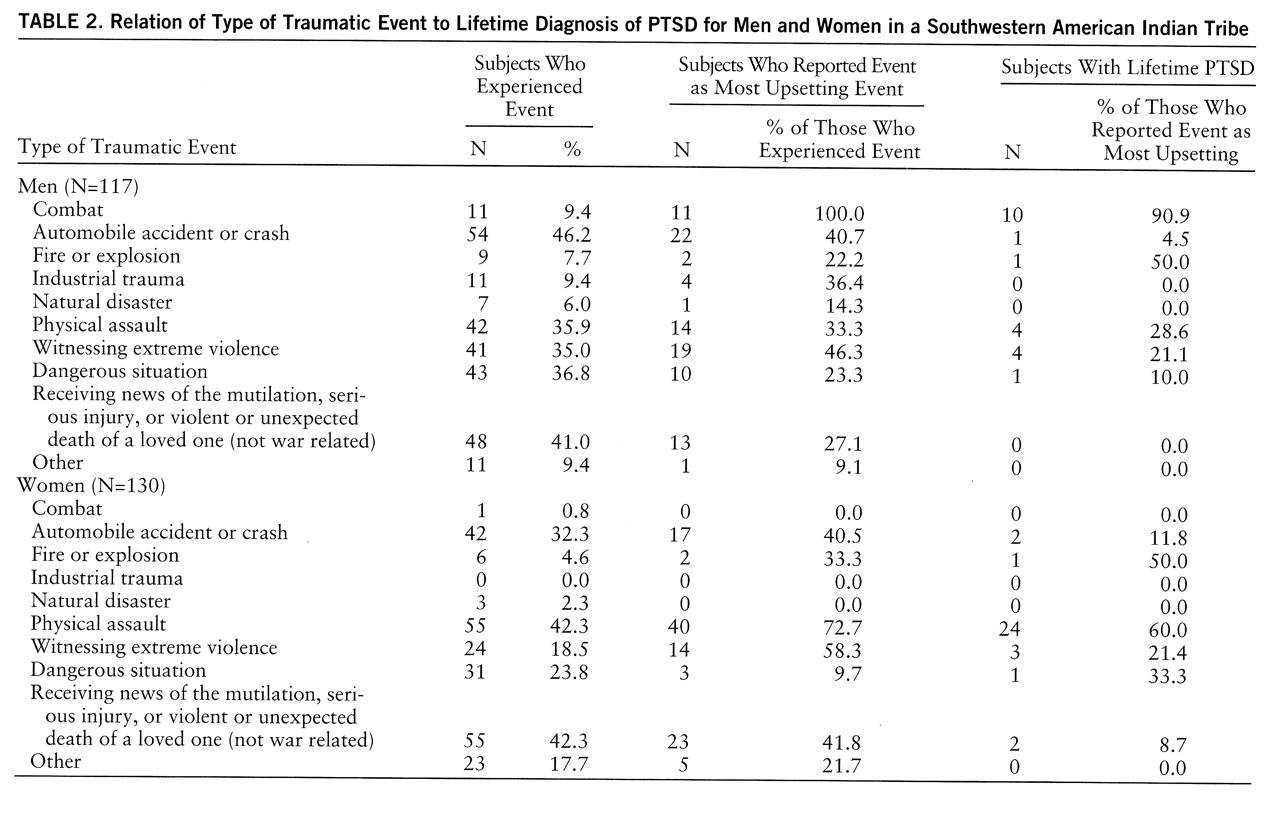

14) was administered consecutively to the last 247 enrolled subjects. This is a simple measure of potential events meeting DSM-III-R criterion A for PTSD and is currently being used in large-scale studies of Southwestern and Plains Indian communities. The booklet presents to the respondent yes-or-no questions about whether he or she has directly experienced or witnessed any of 10 traumatic events during his or her lifetime: combat, accident or crash, fire or explosion, industrial trauma, natural disaster, physical assault, witnessing extreme violence, dangerous situation, receiving news of the mutilation, serious injury, or violent or unexpected death of a loved one (not war related), or other traumatic event. Criterion A traumatic events are described as ones that are unusual, are extremely stressful or disturbing, and do not happen to most people. If several events are recorded, the respondent is asked to cite one event that is perceived as the “most upsetting,” and this event is assessed to determine whether criterion A is met by presenting the first section of the SCID PTSD component. If criterion A is met, the remaining sections of the SCID PTSD component are administered. Combat was treated as a discrete event and was not recorded for other event categories (e.g., dangerous situation, witnessing extreme violence). The temporal occurrence of events was evaluated in the recording of specific incidents of trauma.

Statistical Analyses

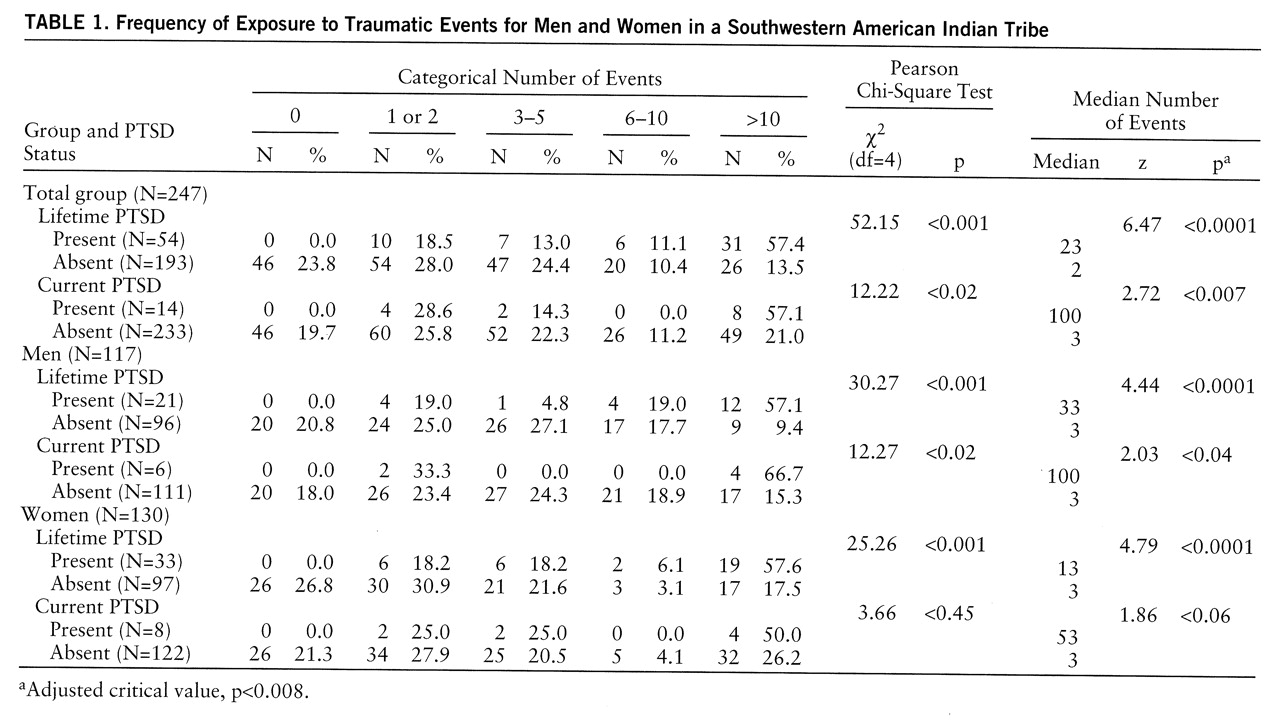

The mean ages at onset of PTSD for men and women were compared by using the t test for unpaired data with unequal variances. The two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to test the equality of the median numbers of traumatic events for individuals with and without a PTSD diagnosis. The numbers of traumatic events experienced were categorized into quintiles of approximately equal size—0, 1 or 2, 3–5, 6–10, and >10—to facilitate further analysis. Pearson chi-square tests were used to determine associations between categorical number of traumatic events and presence or absence of PTSD diagnosis. Odds ratios were calculated for the prevalences of PTSD among men and women and for the occurrence of PTSD and other psychiatric disorders. Corresponding 95% confidence intervals were determined. Critical values were adjusted by using the Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. To evaluate sex, stratum-specific odds ratios were tested by using the Mantel-Haenszel test for heterogeneity. Sex was determined to be an effect modifier for PTSD, and so analyses were performed separately for men and women. Logistic regression was performed by using demographic variables, number of traumatic events, and type of traumatic event. Appropriate models were tested with log likelihoods.

Advantages and Limitations

A potential limitation of the genealogically based sampling strategy for estimating prevalence or collecting subjects with representative typology is that nonrepresentativeness could result from nonexhaustive sampling within families, ascertainment bias, or collection of a sample of families insufficient to describe the target population. The genealogical strategy used here involved comprehensive investigation of a unique population involving large and relatively homogeneous pedigrees. This method resulted in the collection of a large and genetically well-defined study group from a tribal population that is itself well circumscribed genetically, geographically, and culturally. However, our study group was not a randomly selected community-based sample and therefore has inherent limitations and biases. In subsequent analyses, the potential biases enumerated here were kept in mind; for example, data were separately analyzed by sex, and age was covaried. An additional limiting factor is the likelihood that a number of potential subjects were not included in our study population because of early death, including violent death. For this reason, individuals surviving to an older age would reflect an artificially low rate of traumatic events.