The early phase of treatment for major depression poses a significant clinical challenge because antidepressive agents typically take 2–4 weeks to provide substantial benefit, during which time the patient continues to suffer, may stop the treatment regimen, and may become even more discouraged, with an attendant risk of suicide. The problem of slow response may be compounded by the necessity for as many as one-third of patients

(1) to change medications in search of one that is both well tolerated and effective.

A number of controlled studies have combined benzodiazepines with tricyclic antidepressive compounds, demonstrating positive results

(2-

5). Several double-blind investigations have also suggested that some benzodiazepines alone may have an antidepressive effect beyond initial anxiety reduction

(3,

(6-

8). The practice of augmenting antidepressive medication with benzodiazepines has especially gained favor recently since selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

(9) have replaced tricyclic antidepressants as the first line of treatment of major depression. Whereas the tricyclic antidepressants often produce sedation early in treatment, the SSRIs more commonly have side effects of stimulation and sleep impairment

(10-

(12). The high-potency benzodiazepines (clonazepam, alprazolam, lorazepam) are frequently used in clinical practice concurrently with SSRIs in treating major depression, but reports of enhanced efficacy tend to be anecdotal, and a search including the electronic MEDLINE and PsycInfo databases for the last 10 years failed to locate any controlled trials of such combined therapy in the published literature.

The purpose of the present double-blind study was to determine whether augmenting fluoxetine with clonazepam is both safe and more efficacious than fluoxetine alone in the early phase of treatment for major depression.

RESULTS

Disposition of Patients

A total of 85 patients completed the psychiatric and medical examinations with findings that met the screening criteria; however, four of these did not continue to meet all of the entry criteria at day 0 (baseline) and were dropped from the study. Eighty patients were originally randomly assigned to treatment and started taking the medication, but one patient dropped out at day 4 and provided safety data but no efficacy data. Another patient who met all of the entry criteria replaced this subject. Therefore, the overall study group was 80 patients for testing efficacy and 81 patients for safety assessment (intent to treat). Of the 80 patients included in the efficacy evaluation, Scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale Over 8 Weeks for Patients Taking Clonazepam Plus Fluoxetine or Placebo Plus Fluoxetine all 40 of the subjects in the augmentation group completed the first 3 weeks and 37 subjects in the placebo group completed this phase of treatment. Sixty-five patients continued treatment for 8 weeks, for an 81% completion rate.

The 15 patients who terminated treatment prematurely were almost equally divided between clonazepam plus fluoxetine (N=8) and placebo plus fluoxetine (N=7), and they showed similar patterns of reasons for discontinuing, with the exception of a statistically nonsignificant trend for the placebo patients to discontinue treatment because of adverse events (five patients versus one). Of the 40 efficacy patients in the clonazepam group, 33 completed the study (83%). One dropped on day 49 because of adverse events, two dropped because of insufficient clinical response, one was lost to follow-up, one left town, one used a proscribed drug for cough, and one missed study drug dosing for more than 3 days. Thirty-two of the patients treated with placebo completed treatment (80%): five dropped out because of adverse events, two were lost to follow-up, and one was dropped after taking prohibited pain medications for an ankle injury.

Subject Characteristics at Baseline

The efficacy group ranged in age from 20 to 73 years and averaged 41.5 years. More than 90% identified themselves as Caucasians, and the study group consisted of almost equal numbers of men and women (52% female). The research subjects had an average of 14 years of education (SD=2). No significant differences were found on any of these demographic variables. At baseline, the two 40-subject treatment groups had identical mean ratings of 4.4 (SD=0.5) (between “moderately ill” and “markedly ill”) on the Clinical Global Impression of Severity

(24) and similar mean scores on the Hamilton depression scale: 21.7 (SD=2.6) for the clonazepam-plus-fluoxetine treatment group and 22.6 (SD=3.1) for the placebo-plus-fluoxetine group.

Dosing Pattern

By day 10, 24 (60%) of the 40 patients receiving clonazepam had stabilized at two tablets at bedtime (1.0 mg) while 27 (68%) of those in the placebo group had also increased to two tablets. The patients treated with 0.5 mg and those treated with 1.0 mg of clonazepam were similar at baseline on measures of severity; further, the measures of improvement showed no significant differences between these subgroups. Of the 35 patients receiving clonazepam who remained in treatment through day 42, somewhat more than one-half (57%, N=20) were increased to 40 mg/day of fluoxetine (the percentage was essentially the same for both doses of clonazepam). Thirty-two patients treated with fluoxetine alone were still in treatment at day 42, and 59% of them (N=19) had the fluoxetine dose raised to 40 mg.

Efficacy

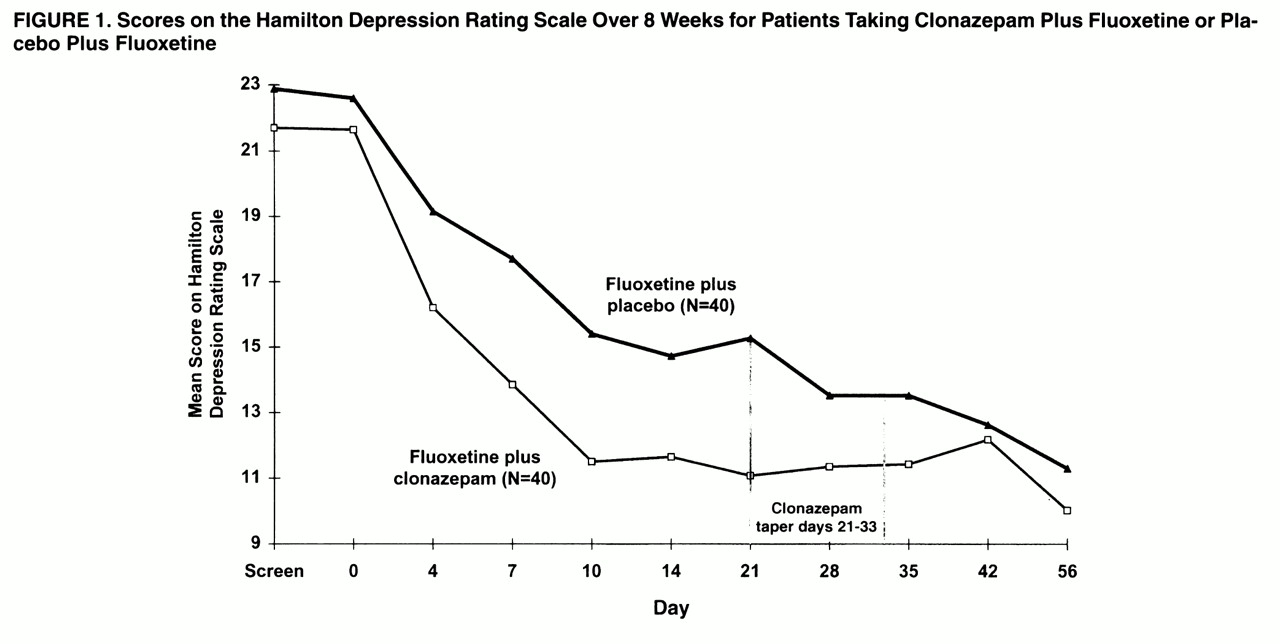

Patients in both treatment groups improved over the course of the study, as reflected by changes in mean scores on the Hamilton depression scale (

figure 1). Two-group repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant treatment-by-time interaction (F=2.55, df=9, 702, p=0.03, with the Greenhouse-Geisser correction). Pairwise comparison of Hamilton depression means scores by Fisher’s least significant difference first showed that the augmentation group had improved significantly more than the group receiving fluoxetine plus placebo at day 7 (p=0.002). The clonazepam patients also had significantly lower Hamilton depression scores at day 10 and again at day 21 (p<0.001). By day 28, 1 week after the clonazepam discontinuation schedule was initiated, there was no significant difference between clonazepam augmentation and placebo. The graphic display reveals that the Hamilton depression scores for the clonazepam group increased slightly during the taper (day 35) and the first week after discontinuation (day 42).

Figure 1 also shows that the patients receiving placebo continued to improve, so that the mean Hamilton depression scores were similar for the two treatment groups by day 42, and they remained so at day 56, when both groups reached the point of greatest reduction in depression symptoms.

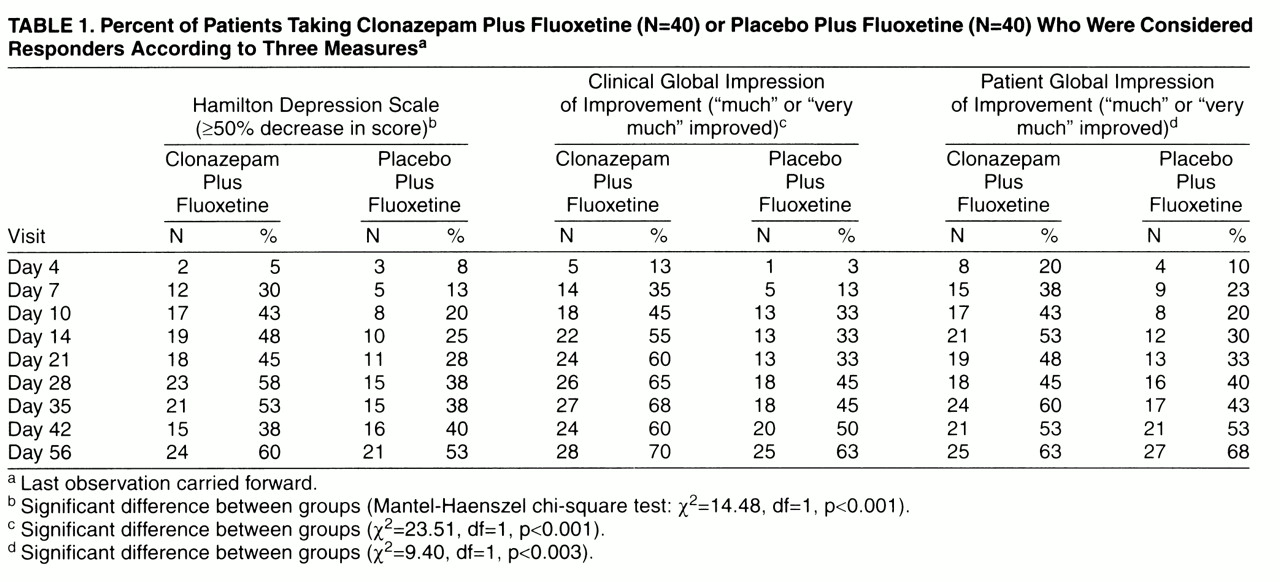

The patients were declared to be “responders” or “nonresponders” to treatment by three different standard measures: the Hamilton depression scale, a clinician’s overall judgment of improvement (Clinical Global Impression of Improvement), and the patient’s own estimate of at least “much improved.” The rates of response from day 4 to day 56 study are shown in

table 1. Significantly more of the patients treated with clonazepam augmentation had an improvement of at least 50% on the Hamilton depression scale, gained ratings of “much” or “very much” improved on the Clinical Global Impression of Improvement, and reported themselves “much” or “very much” improved. The overall difference in frequencies of positive response over the nine data points was significant for each of these measures according to the Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test (χ

2=10.35, df=1, p<0.0001). An exception to the pattern of results was the decrease in the percentage of responders in the augmentation group on all three measures at day 42, 9 days after clonazepam discontinuation, before reaching the highest rates 2 weeks later (day 56). This result confirms the temporary reversal of improvement observed at day 42 in mean scores on the Hamilton depression scale (

figure 1).

Safety

Discontinuation because of adverse events

No serious adverse events were reported in the experimental or control group. Of the 81 patients who took medicine, six terminated treatment prematurely because of adverse events—one who was treated with clonazepam plus fluoxetine and five who were treated with placebo plus fluoxetine (Fisher’s exact test, p>0.10). The single early termination in the augmentation group, occurring on day 49, was attributed to decreased appetite, nervousness, nausea, poor concentration, sleepiness, fatigue, decreased libido, and headache. The remaining early terminators, all treated with fluoxetine only, stopped treatment during the first 3 weeks of treatment, as follows: one patient at day 4 with headache and agitation; one patient at day 7 with lightheadedness, nausea, and anxiety, which resolved with discontinuation of placebo; and three patients at day 21, one with stomach cramps, diarrhea, diaphoresis, increased anxiety and anxiety attack, jitteriness, shaky voice, restlessness, insomnia, and nightmares, one patient with lightheadedness, headaches, diarrhea/loose stool, and nausea, and one patient with drowsiness/sedation.

Frequency of adverse events

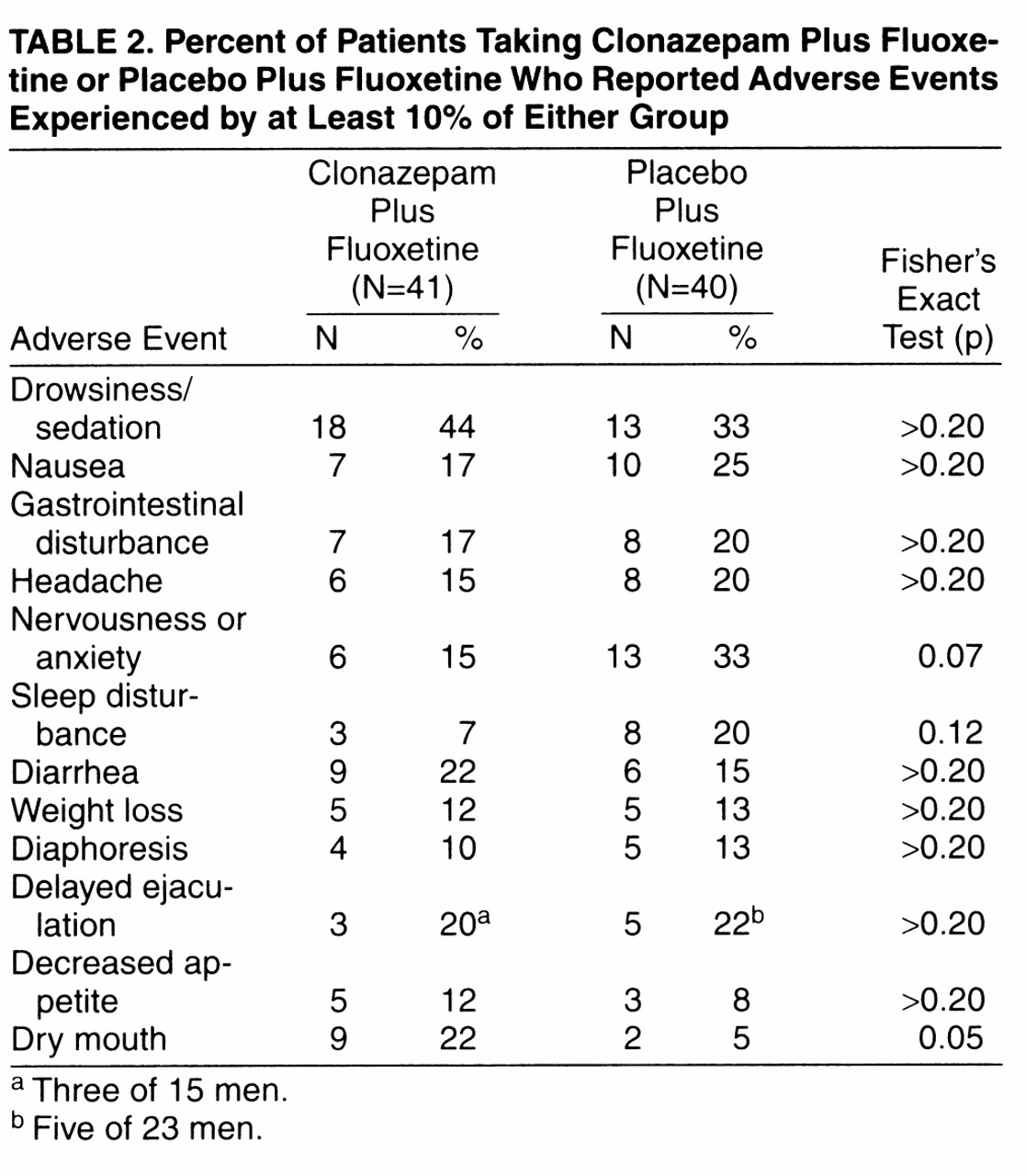

The patients receiving clonazepam experienced less anxiety and sleep disturbance during the 8 weeks of treatment, although the difference was not statistically significant. Not surprisingly, these patients were more likely to experience sedation. The only difference that was statistically significant by Fisher’s exact test was dry mouth (

table 2).

More patients in the placebo group (N=10) complained of new or worsened side effects during the clonazepam/placebo taper and immediately after discontinuation (day 22 to day 42) than did patients in the clonazepam augmentation group (N=4). The majority of these patients in both groups were tapering from two clonazepam/placebo tablets over 2 weeks (seven of the 10 placebo patients, and three of the four clonazepam patients). A total of nine adverse events were reported by the four clonazepam patients complaining of new or worsened side effects during taper: 1) headache, nightmares, insomnia, and diaphoresis (day 30); 2) delayed ejaculation (day 32); 3) restlessness (day 25), weight loss (day 28), and indigestion (day 30); and 4) heartburn (day 23). The 10 patients tapering from placebo reported a total of 15 adverse events: 1) increased dreaming (day 22), constipation (day 22), and tinnitus (day 30); 2) agitation (day 31); 3) restlessness (day 22); 4) sedation (day 30); 5) panicattack (day 30) and delayed ejaculation (day 33); 6) CNS stimulation (day 29); 7) constipation (day 28); 8) weight loss (day 29); 9) nightmares (day 22), heartburn (day 28), and decreased libido (day 32); and 10) dry mouth (day 29). It should be recalled, however, that the clonazepam group’s efficacy scores deteriorated temporarily after the taper was completed, especially at day 42, 9 days posttaper. After the day-42 ratings were recorded, the majority in each group increased the fluoxetine dose to two 20-mg capsules each day. Of the nine patients who complained of late-appearing adverse events, starting day 43 through day 49, eight were taking the increased dose of fluoxetine. Adverse events that were first recorded or that worsened after the increase in fluoxetine dose were as follows: diaphoresis (N=3), dry mouth (N=2), decreased libido (N=2), sedation (N=2), anxiety (N=1), initial insomnia (N=1), muscle twitching (N=1), and weight loss (N=1).

There were no clinically significant changes in laboratory test results or ECGs from screen to endpoint with one exception. Patient 4, in the clonazepam group, terminated treatment at day 21 because she used an analgesic for a concomitant illness, and she had high levels of SGOT (154 U/liter), SGPT (167 U/liter), and GOT (142 U/liter). Her case was followed for several weeks until her laboratory values returned to normal, after it was discovered that she had been ingesting significant levels of insecticide in vegetables from a neighbor’s garden.

DISCUSSION

This investigation demonstrated that clonazepam augmentation of fluoxetine was superior to fluoxetine alone in relieving the symptoms of moderate to marked major depression during the first phase of treatment, especially the first 3 weeks. The rapidity of response was most striking: patients receiving clonazepam achieved in 10 days the same improvement on the Hamilton depression scale that fluoxetine alone reached by day 56. Similarly, 43% of the patients receiving clonazepam rated themselves as “much” or “very much” Improved by day 10, a proportion not matched by fluoxetine alone until 5 weeks into treatment. The findings were consistently significant over a variety of outcome measures based on clinician judgments and reports from patients.

These results are apparently the first to confirm, in a controlled trial, the efficacy of augmenting an SSRI with a benzodiazepine. This evidence of the enhanced efficacy of augmentation therapy is compatible with anecdotal reports from clinical practice

(2,

10) and earlier studies of combining benzodiazepines efficaciously with tricyclic antidepressants

(2-

5). Our findings tend to support the typical rationale for augmentation with benzodiazepines, that is, reduction of the anxiety and insomnia components of the illness and suppression of the stimulating side effects of the SSRI

(9,

11,

12). The findings do not specifically support but are consistent with suggestions that high-potency benzodiazepines, such as alprazolam

(3,

6) or adinazolam

(7, (30) may have a direct antidepressive effect

(8).

Our study did not replicate the 60% rate of positive response to fluoxetine after 3 weeks that has been reported by some investigators

(12), but our result is consistent with reports that one-third or more of patients may be unresponsive to an adequate trial of SSRIs

(1). Further, almost 60% of both study groups required an increase in fluoxetine dose at week 6, whereas in an earlier study

(31) only 37% of patients required a dose increase after 4 weeks. The difference in these results may in part be related to the timing of the dose adjustment, i.e., 4 versus 6 weeks of treatment. The longer a patient has been treated without a satisfactory response, the more likely a clinician is to increase the dose or change medications. In the present group of depressed outpatients, fluoxetine appeared to produce a slow, steady positive response that was still increasing at the end of 8 weeks.

There was suggestive evidence of a temporary increase in symptoms after clonazepam was discontinued, possibly reflecting a mild rebound, loss of suppression of some SSRI side effects, or both. Discontinuation of augmentation confounds at least three potential factors: 1) elimination of directly additive and/or synergistic treatment effects on the symptoms of depression, 2) removal of possible suppression of fluoxetine side effects, 3) a withdrawal syndrome or lesser physiologic adjustment. This complex mixture of symptom return and emergence of medication side effects requires cautious interpretation (for example, if a patient experienced insomnia during the clonazepam taper period, it would be difficult to determine to what extent the change was due to adjustment to medication withdrawal per se versus reduction in antidepressant effect versus unmasking of fluoxetine side effects). A specific point at issue is the temporary reversal of improvement in the augmentation patients at day 42, 9 days after discontinuation of clonazepam. This regression in response may reflect all of the factors just listed, especially in the context of an increase in new adverse events most characteristic of fluoxetine side effects. At this point, it may be prudent to expect that some patients will temporarily display a reversal of treatment response due to discontinuation of clonazepam augmentation, even from a low dose.

Overall, clonazepam augmentation therapy was shown to be a safe and effective treatment modality for major depression in the low dose range (0.5 mg or 1.0 mg) prescribed in this research protocol. The results included no serious adverse events, and the group receiving clonazepam plus fluoxetine had fewer premature terminations for side effects than fluoxetine alone. The long half-life of clonazepam

(18) probably minimized rebound anxiety

(19,

20) without the use of a long taper period, although there was some evidence of a temporary reduction of benefit during taper. Only one patient treated with clonazepam (0.5 mg) discontinued treatment because of an adverse experience. In this case, the adverse events appeared during the taper schedule. The overall pattern of results suggested that some other patients experienced a plateau in improvement, a mild, transitory worsening of depression symptoms, or an increase in SSRI side effects when clonazepam was discontinued. However, it should be kept in mind that augmentation was associated with fewer adverse events and terminated cases because of side effects, although the difference in rates was not statistically significant.

Generalization of the clonazepam augmentation strategy to other SSRIs might involve different dosing, based on the pattern of inhibition the specific SSRI demonstrates for the cytochrome isoenzyme CYP3A4, which is central in the metabolism of clonazepam

(32-

34).

The results of this study indicate that augmentation of fluoxetine with low-dose clonazepam during the first 3 weeks of treatment is safe and more efficacious than fluoxetine alone for moderate-to-marked depression. Augmentation therapy has the advantage of reducing suffering during the period it takes an antidepressive drug to become effective. The addition of the high-potency benzodiazepine seems to help suppress the anxiety and insomnia often experienced in adjusting to an SSRI and may be associated with a lower rate of adverse events. Clonazepam augmentation has the potential value of increasing compliance, especially if there is a need to change the SSRI in search of one that is better tolerated, and faster relief may reduce the risk of suicide at the start of treatment. The discontinuation of augmentation appeared to be associated with mild, transitory worsening of symptoms.