Considerable information is now available about the clinical features, treatment, and outcome of bipolar illness. However, despite advances in our understanding of the phenomenological aspects of manic depression, there are few biological markers. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides an opportunity to better understand the neuroanatomical substrates underlying this illness. The fact that patients with bipolar disorder who have MRI findings often have a family history of the disorder raises the possibility that such findings may correlate within families and could potentially allow clearer characterization of the genetics of the disorder.

Imaging studies in bipolar disorder allow one to observe deep white matter and subcortical changes, which are seen as focal signal hyperintensities on T

2-weighted MRIs. Dupont et al.

(1) first observed white matter hyperintensities in up to 25% of young patients with bipolar disorder, findings that they reported to be stable over time. Others

(2, 3) have replicated these findings, and a study of never-treated patients with bipolar disorder found a similar trend that did not reach significance

(4). The clinical significance of these MRI findings has yet to be determined.

White matter lesions are commonly found in elderly subjects. Bradley et al.

(5) found that 30% of patients over 60 years old had leukoencephalopathic changes according to MRI. Notably, white matter hyperintensities are not normally seen in younger subjects. George et al.

(6) found no white matter lesions in subjects who were 45 years old or younger. In previous work

(7), we found white matter hyperintensities in 40% of a group of control subjects but in only 1% of the control subjects who were 45 years old or younger. In the current study, we investigate whether the rate of deep white matter hyperintensities and subcortical hyperintensities is greater in families in which there is a strong genetic loading for bipolar illness.

METHOD

A family with a substantial history of bipolar disorder was recruited from the Affective Disorders Program at Duke University Medical Center. Informed written consent was obtained from 23 of the family members. Participants were then interviewed by one of four psychiatrists (E.P.A., D.C.S., F.C., or S.A.V.M.) using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R

(8). A detailed database, adopted from the Duke Depression Evaluation Schedule

(9), was completed. Atherosclerotic risk factors were noted; these included smoking, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and a history of cardiac or cerebrovascular disease. Following the structured interview, a standardized diagnosis was determined by consensus for each subject during a diagnostic conference involving at least three psychiatrists, including the primary interviewer. Diagnostic information on family members not present or deceased was obtained from three reliable family informants, and the diagnostic category was assigned by consensus opinion of three clinicians (E.P.A., D.C.S., and S.A.V.M.).

Twenty-one of 23 family members volunteered for MRI. Brain MRIs were performed with a General Electric 1.5 T Signa system. Five-mm thick T1-weighted (TR=500 msec, TE=20 msec) and T2-weighted (TR=2500 msec, TE=40/80 msec) 1H spin-echo pulse sequences were used to image the subject’s brain in the head coil of the MRI system. MRI scans were then assessed by using the modified Fazekas scale for the number, size, and location of white matter and subcortical gray nuclei lesions by two raters (J.M.P. and K.R.R.K.), who were blind to the patients’ diagnoses. Cohen’s kappa was calculated for the level of interrater agreement. Consensus opinion was then reached for all scans. An unpaired t test was used to compare the mean ages of the family members with positive and negative findings to assess whether there was an age-related effect.

RESULTS

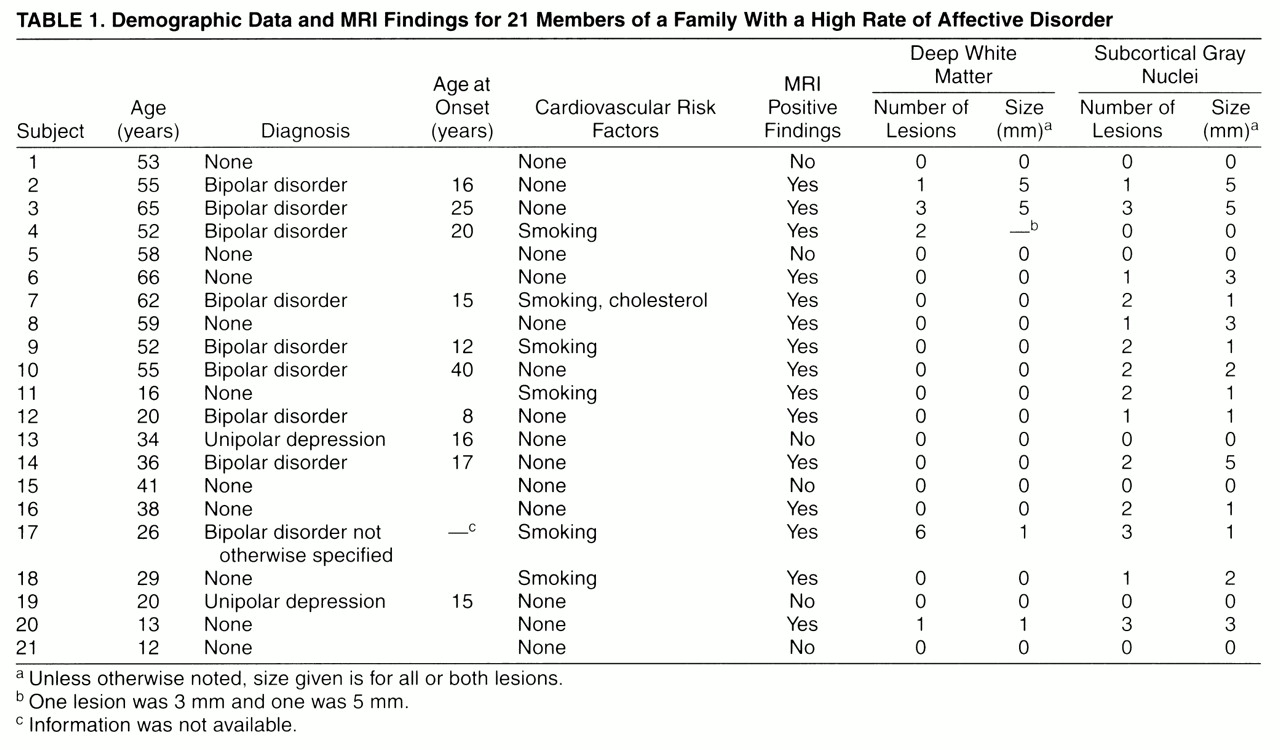

The family pedigree (

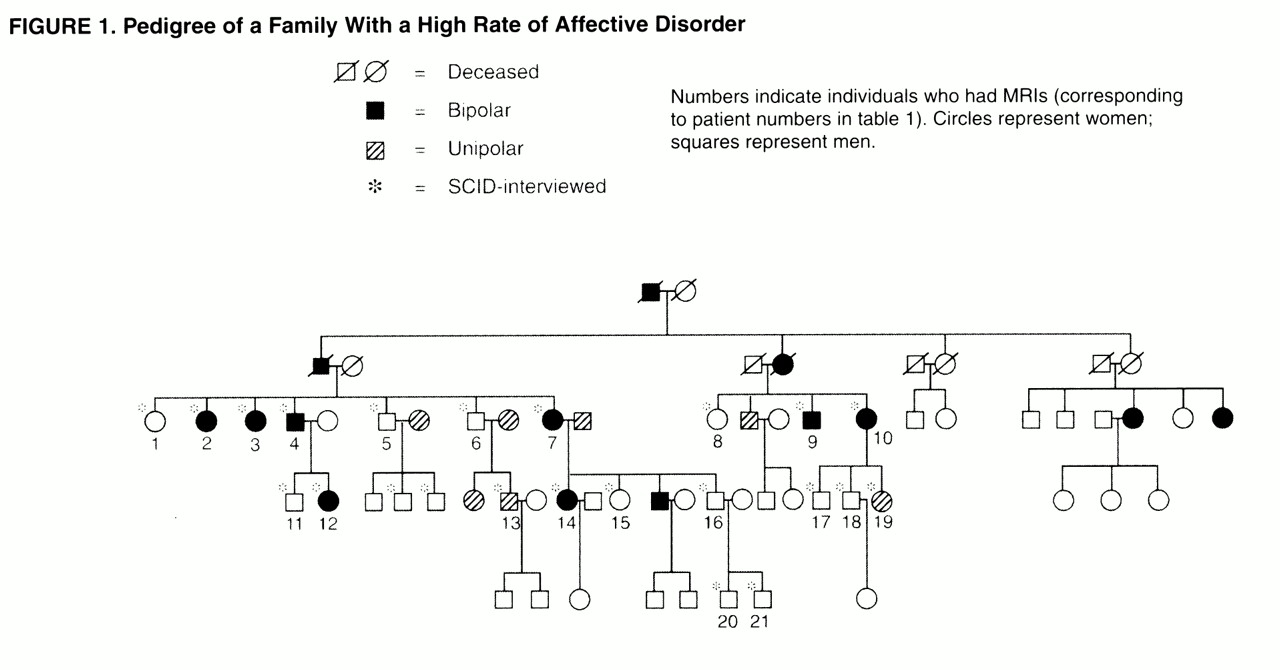

figure 1) demonstrates the rate of bipolar illness. Bipolar disorder was present in 14 (22%) of 65 family members. The rate of unipolar illness was 11% (seven family members). Of the 21 family members who had MRIs, eight had bipolar illness, one had symptoms of bipolar disorder but did not meet full DSM-III-R criteria, and two had unipolar illness. The mean age of the MRI participants was 41 years (range=12–66). The mean age at onset of bipolar illness was 18 years (range=8–40). Atherosclerotic risk factors were not striking (

table 1).

A summary of demographic data and MRI findings is found in

table 1. Interrater reliability for the interpretation of MRI scans was high (Cohen’s kappa=0.58). Points of disagreement were resolved by consensus opinion. Fifteen of the 21 family members had MRI findings, including six unaffected family members and all family members with bipolar disorder. Four of nine family members with bipolar disorder had deep white matter changes and eight had lesions of the subcortical gray nuclei. Neither of the two family members with unipolar illness had MRI findings. Of 10 family members with no affective illness, six had lesions in the subcortical gray nuclei. One of the six also had a white matter lesion. The size of lesions varied in this family from 1 mm to 5 mm. There was no significant correlation between lesion size or type (subcortical gray or white matter) and diagnosis. For lesions of white matter and subcortical gray nuclei, an unpaired t test comparing mean age of groups with and without MRI findings failed to demonstrate any age effect (white matter p=0.77, subcortical gray nuclei, p=0.90).

DISCUSSION

These preliminary data demonstrate a high prevalence of both white matter and subcortical findings in the family members who had bipolar disorder. White matter findings have been reported in young patients with bipolar disorder. The early data from this study seem to indicate a high prevalence of both white and subcortical findings in this “loaded” pedigree. Further, the prevalence of MRI findings in unaffected family members was high. The rate found is higher than that reported for control subjects in general

(5–7). Of note, one unaffected family member is still a preadolescent and may yet manifest the disease. Age was not a significant factor when the family members with and without positive findings were compared. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a high prevalence of white matter and subcortical findings in family members of patients with bipolar disorder.

The clinical implications of MRI findings in patients with bipolar disorder and in their family members are not known. Only in late-onset bipolar disorder (onset after the age of 50) have organic factors been established as a frequent etiologic mechanism for the development of the illness

(10, 11). Further research is needed to understand the MRI findings described herein and to establish the underlying pathophysiology. The high prevalence of white matter and subcortical findings in both affected and unaffected family members raises the possibility that these changes may serve as a biological marker for the illness. Further, recent genetic research has established a link between familial arteriopathy with subcortical leukoencephalopathy and chromosome 19

(12). Notably, in one study of nine families with this disorder

(13), 22% had mood disorders. The MRI changes reported in bipolar illness may potentially correlate with genetic factors related to this disorder.