Depression is common among cocaine-dependent patients

(1, 2). Poor adherence with outpatient treatment among cocaine-dependent patients is well documented, and the majority drop out within 1 month of treatment

(3). Cocaine-dependent patients treated on an inpatient psychiatric unit for depression who drop out of outpatient treatment before completion of month 1 are at significant risk of rehospitalization (our unpublished data). There is a need for strategies to improve these patients’ motivation to adhere with outpatient treatment. Although motivational interventions have been employed for alcohol use disorders

(4), there is a paucity of empirical data on motivational strategies for depressed cocaine-dependent patients.

This pilot study aimed to investigate whether individual and group motivational therapy sessions would improve adherence to and completion of the initial 30 days of outpatient treatment among depressed cocaine-dependent patients. We hypothesized that motivational therapy would have better treatment adherence and completion rates than treatment-as-usual.

METHOD

The study included 23 patients discharged from a university psychiatric hospital’s dual diagnosis unit. Patients were evaluated by a primary nurse or psychiatric resident and a faculty psychiatrist. Diagnoses were made through use of the DSM-IV multiaxial format. To be eligible for inclusion, patients had to have a depressive disorder requiring antidepressant therapy and a cocaine dependence disorder and had to attend an initial outpatient treatment session following hospital discharge.

Study patients were similar in method of cocaine administration used, number of substances abused, and types of medications used for the treatment of depression. All motivational therapy patients met DSM-IV criteria for cocaine (crack) dependence; 91% met criteria for alcohol dependence (mean=2.27 substance use disorders, SD=0.47); 82% met criteria for major depression; and 18% met criteria for depressive disorder, not otherwise specified. All treatment-as-usual patients met criteria for cocaine (crack) dependence; 91% met criteria for alcohol dependence (mean=2.17 substance use disorders, SD=0.39); 42% met criteria for major depression; and 58% met criteria for depressive disorder, not otherwise specified. All patients were taking antidepressants at the time of treatment entry; all but one were taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. The mean number of medications taken was 1.64 (SD=0.67) for motivational therapy patients and 1.50 (SD=0.67) for treatment-as-usual patients.

The mean age of all patients was 33.6 years. Sixty-one percent were male, 74% African American, 74% single, and 91% unemployed. The mean education was 12.4 years. Sixty-two percent had recurrent major depression, and 38% had depressive disorder, not otherwise specified.

The two groups were similar in age, marital status, education, and employment status. Furthermore, the two treatment groups did not differ in terms of prior psychiatric hospitalizations. The motivational therapy group had more Caucasians (45%) than the treatment-as-usual group (8%). Recurrent major depression was more common among motivational therapy patients (85%) than among treatment-as-usual patients (42%). After a description of the study was provided, written informed consent was obtained.

The motivational therapy group included 11 subjects consecutively admitted to outpatient care following inpatient treatment. Motivational therapy integrates dual disorders recovery counseling

(4) with motivational therapy

(5). This is an integrated treatment approach addressing substance use and psychiatric issues and aims to help patients anticipate and cope with external situations or internal problems that contribute to poor adherence. Motivational therapy is based on the motivational interviewing approach of Miller and colleagues and is designed to mobilize the patient’s own internal change resources

(5). Motivational therapy is summarized by the acronym FRAMES and involves providing

Feedback to the patient on substance use and mood problems, emphasizing personal

Responsibility for change, providing

Advice on how to change, providing a

Menu of change options, being

Empathic toward the patient, and facilitating the patient’s

Self-efficacy or optimism regarding positive change

(5). All patients were eligible to attend five individual and four group sessions during month 1. The comparison group included the previous 12 patients consecutively admitted to outpatient care, who received treatment-as-usual. Treatment-as-usual, which combined pharmacotherapy with supportive therapy, provided psychoeducation on dual disorders and focused on encouraging patients to attend Narcotics Anonymous and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings in the community.

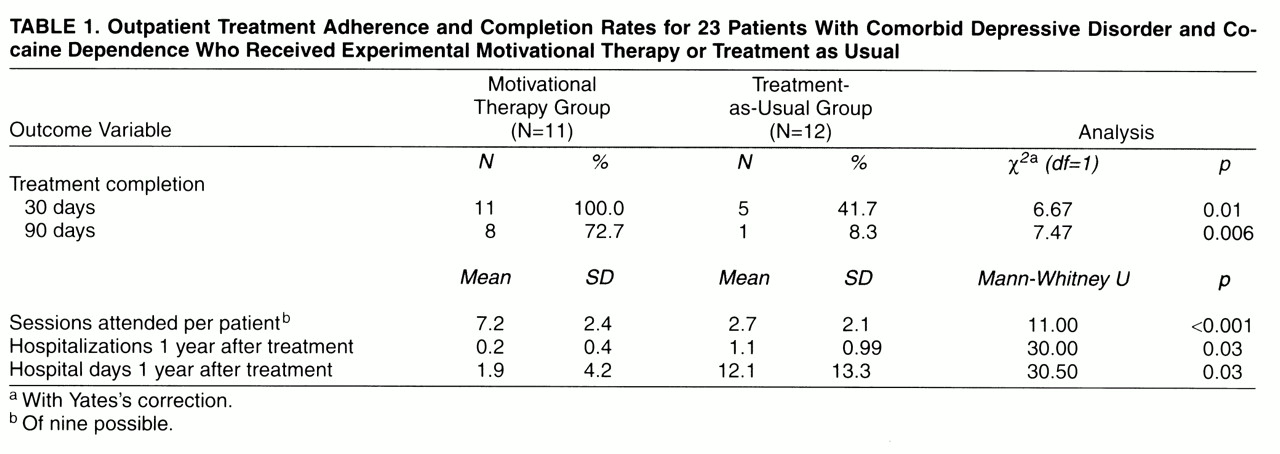

Primary outcome variables were 30-day treatment completion rates and mean number of sessions attended. Secondary outcome measures were 90-day treatment completion rates and psychiatric rehospitalization rates within 1 year of entering outpatient treatment. The Beck Depression Inventory was administered at outpatient visits during month 1.

Given the small group size, motivational therapy and treatment-as-usual groups were compared by using chi-square analysis with Yates’s correction and the Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test; exact significance levels were reported.

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that patients with depression and cocaine dependence can improve adherence and completion rates for the first 30 and 90 days of outpatient care when they are exposed to motivational therapy combining individual and group sessions. These patients improve in sobriety status and mood and are more likely to complete 90 days of treatment than are treatment-as-usual patients. Since length of time in and intensity of treatment are important variables in treatment effectiveness

(6), these are important preliminary findings.

Motivational therapy patients were rehospitalized at a significantly lower rate than treatment-as-usual patients, thus leading to a substantial savings—only two motivational therapy patients were rehospitalized at 1 year after entry into outpatient treatment, while eight of 12 treatment-as-usual patients were rehospitalized a total of 13 times and used 124 more hospital days than motivational therapy patients. Treatment-as-usual patients experienced greater clinical deterioration than motivational therapy patients.

Limitations of our study include the following: 1) the motivational therapy interventions are still being fine-tuned and developed, 2) we did not examine the therapeutic alliance between patient and clinicians, 3) patients were not randomly assigned to the motivational therapy or treatment-as-usual condition because we used two cohorts of consecutively admitted patients, 4) the study group was small, and 5) we used patient self-report measures in gathering information on substance use and did not have laboratory data or collateral reports to verify patients’ reports. Despite these limitations, it appears that motivational therapy can improve outpatient treatment adherence and completion, which in turn reduces the risk of psychiatric rehospitalization. We are now conducting a randomized clinical trial using operationalized motivational therapy and treatment-as-usual protocols that include the use of taped sessions and adherence scales to rate the therapy sessions in order to test our hypotheses on a larger group size.