Neuropsychological Testing

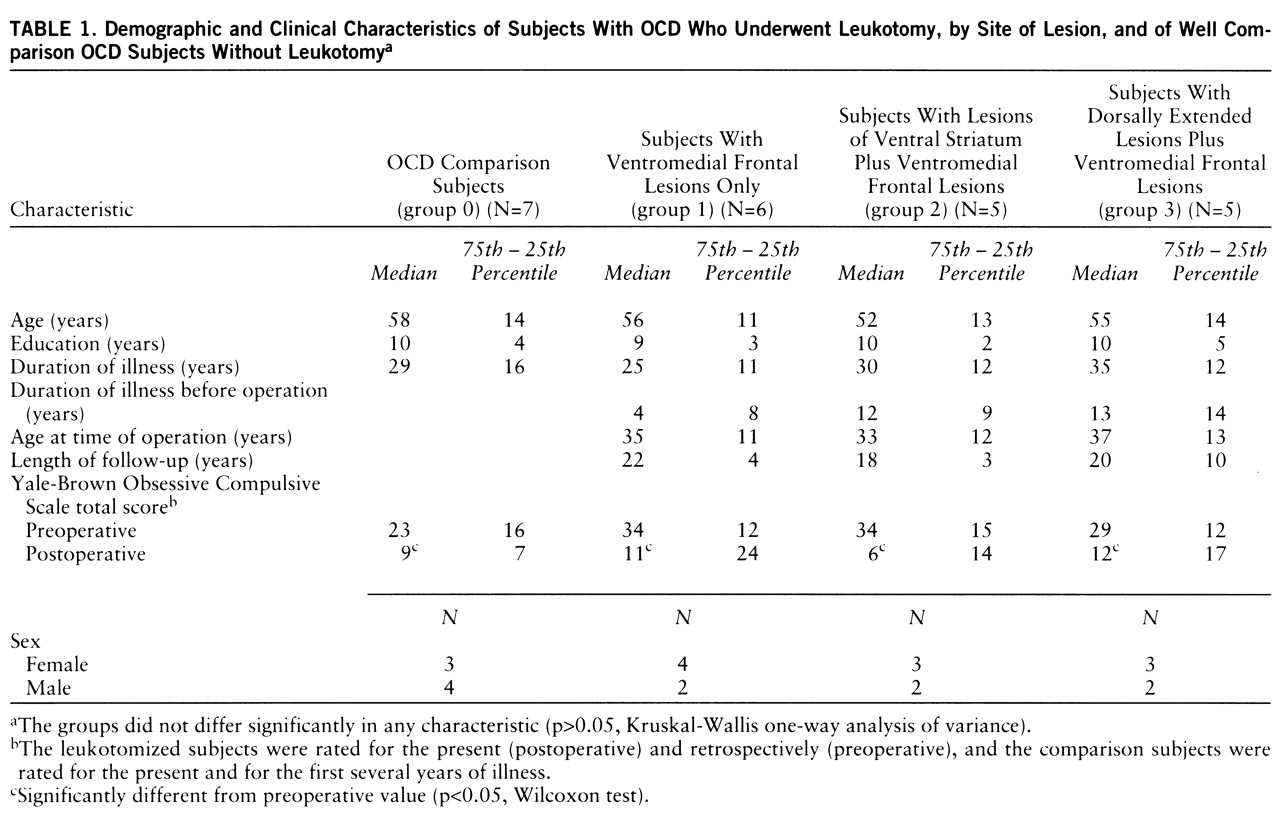

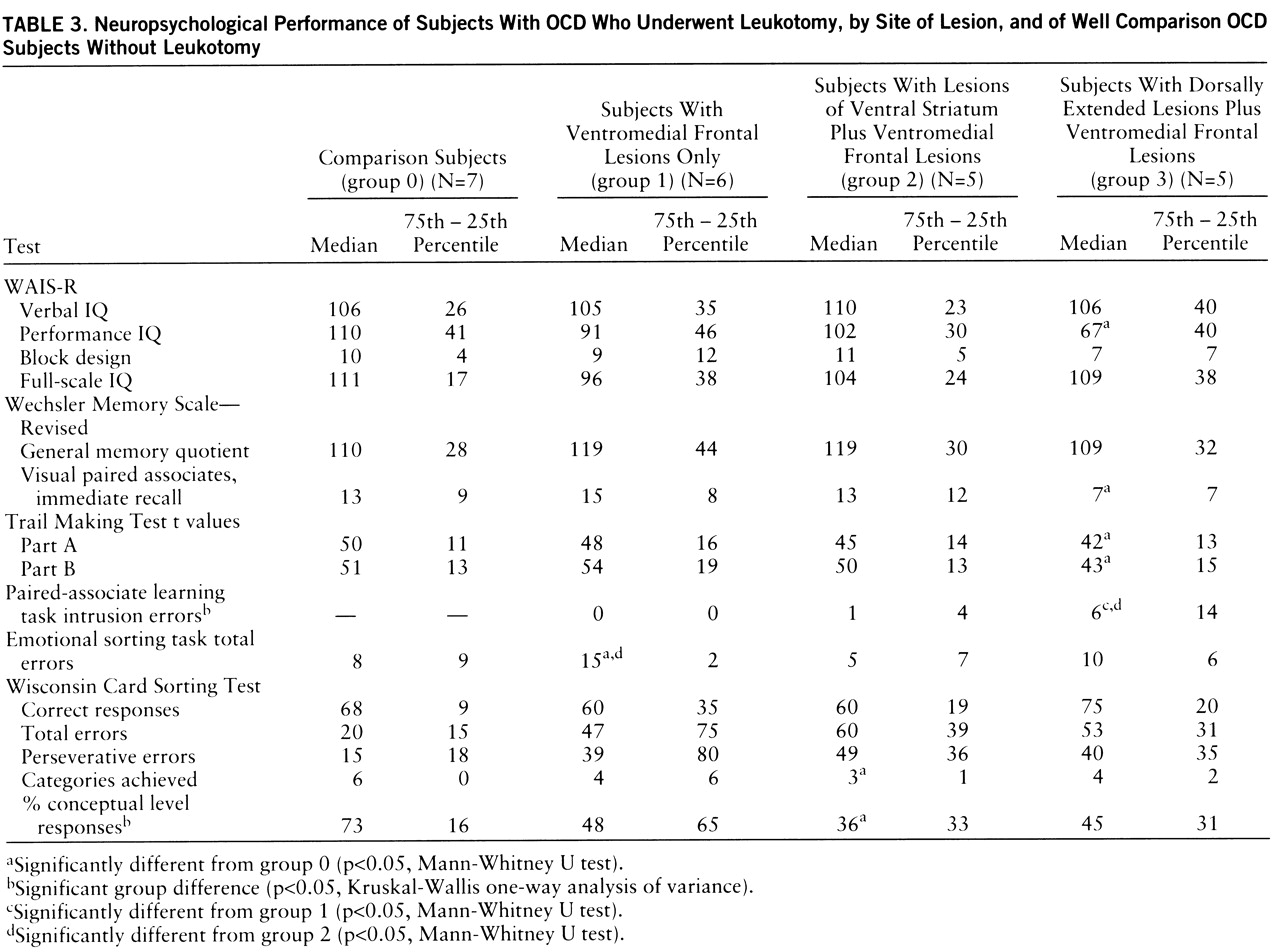

The neuropsychological test results of all groups are summarized in

table 3. No significant group differences were found for verbal or full-scale IQ (WAIS-R) among any of the groups, including the comparison group. However, group 3 (with dorsally extended lesions plus ventromedial frontal lesions) had a significantly lower performance IQ than the comparison group (U=5.0, p<0.05). Three of the five subjects in group 3 performed poorly on performance-related tasks, achieving performance IQ scores of more than two standard deviations below average.

There was no significant group difference for the overall memory quotient yielded by the revised Wechsler Memory Scale, although group 3 scored significantly below the comparison subjects on one subtest of nonverbal memory—visual paired associates, immediate recall (U=5.5, p<0.05). Significant group differences were seen for the number of intrusion errors in the paired-associate learning task (χ2=7.8, df=2, p<0.05). Post hoc analyses revealed that group 3 made significantly more intrusion errors than group 1 (U=1.5, p<0.04) and group 2 (U=0.0, p<0.03). All of the subjects in group 3, one subject in group 2, and none of the subjects in group 1 had scores on this test below the 16th percentile of a normal comparison population.

All three lesion groups showed marked difficulties with the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Significant group differences were seen for the percentage of conceptual level responses (χ2=8.2, df=3, p<0.05). The subjects in group 2 (lesions of the ventral striatum plus ventromedial frontal lesions) were the most impaired, producing significantly fewer categories (U=3.0, p<0.02) and more perseverative and total errors than the comparison subjects. However, on a sorting test for emotional stimuli (pictures from the Ekman series), the performance of the group 2 subjects was similar to that of the comparison subjects (group 0), but group 1 (with ventromedial frontal lesions only) performed significantly worse than group 0 (U=3.0, p<0.02) and group 2 (U=2.0, p<0.02).

All groups, including the comparison group, showed reaction times below the 16th percentile of a normal control population on the computerized tests of attentional performance, except for the go/no-go subtest. The subtest for divided attention yielded the worst results; i.e., 16 of the 22 study subjects (including six out of the seven comparison subjects) showed reaction times below the 16th percentile. The performance on the Trail Making Test was for most subjects within the normal range for a comparison population. However, the group 3 subjects were significantly slower than the comparison subjects (part A: U=5.5, p<0.05; part B: U=5.0, p<0.05). Group 3 also had longer reaction times than group 2 on two of the computerized tests of attentional performance, divided attention (U=2.0, p<0.04) and go/no-go (U=1.5, p<0.02). Reaction time on the go/no-go task was also significantly longer for group 1 than for group 2 (U=1.5, p<0.02).

Clinical Assessment

On the basis of detailed reviews of case notes, the SCID-P, and two independent psychiatric interviews, it could be established that at the time of their operations all of the leukotomized subjects had met the DSM-III-R criteria for severe and chronic OCD and that the OCD had been refractory to extensive trials with nonsurgical psychiatric treatments (e.g., antidepressant medication, various kinds of psychotherapy, electroconvulsive shock, sleep therapy). The clinical records of eight subjects contained reports of at least one suicide attempt. Three subjects (numbers 47 and 81 in group 1 and number 80 in group 3) additionally met the DSM-III-R criteria for obsessive personality disorder. All of the subjects in the comparison group met the criteria for OCD, and none had an additional diagnosis of obsessive personality disorder.

According to Wilcoxon tests, the three lesion groups had significant improvements in their scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale between the (retrospectively rated) presurgical state and the current postsurgical state (group 1: z=–2.2, p<0.03; group 2: z=–2.0, p<0.05; group 3: z=–2.0, p<0.05) (see

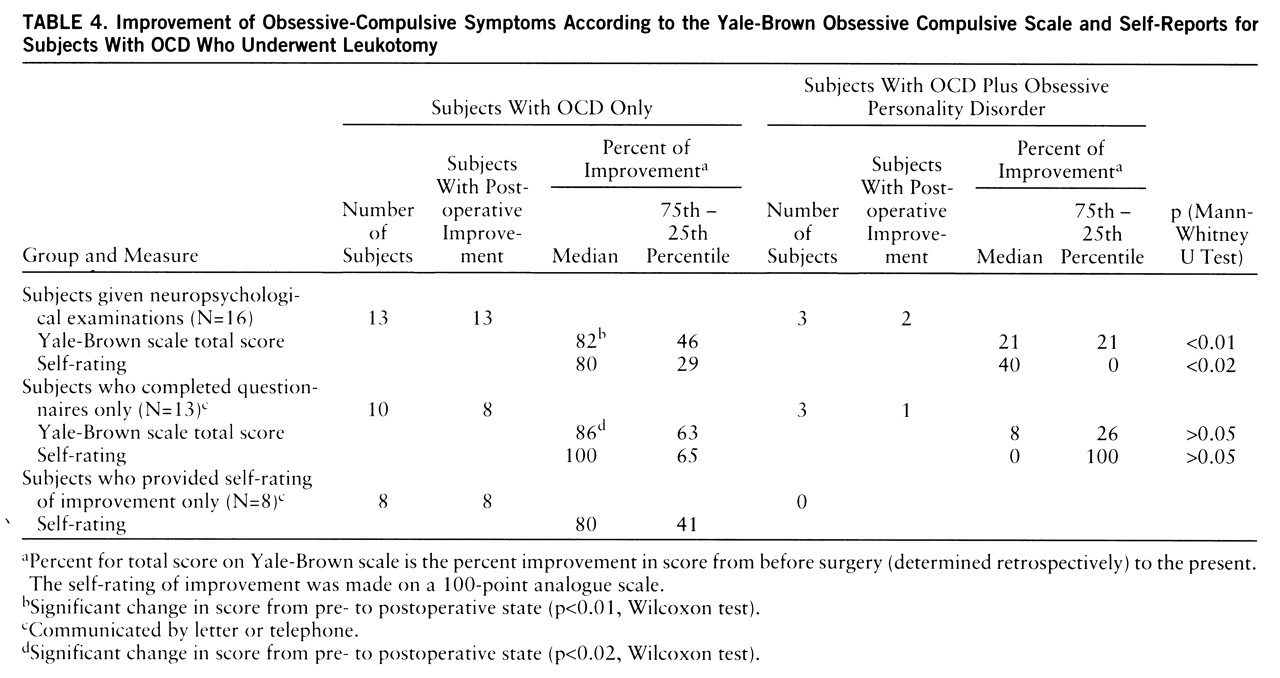

table 1). The subjects in the comparison group significantly improved as well (z=–2.02, p<0.05). Groups 1 and 2 had strong, similar median levels of improvement on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (73% and 75%, respectively), but group 3 improved less (56%). However, these differences did not reach conventional levels of significance. The scores of the subjects with both OCD and obsessive personality disorder (N=3) differed from those of the subjects with OCD only (N=13), and the subjects with both OCD and obsessive personality disorder showed significantly less improvement (U=1.0, p<0.01) (

table 4). Two of the OCD subjects with obsessive personality disorder (subjects 47 and 80) and two subjects with OCD (subjects 66 and 77) were receiving clomipramine at the time of the study. The present scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale of the two OCD subjects (16 and 10, respectively) were well within the range of the scores for the other OCD subjects, lending further support to the idea that the clinical outcomes of the leukotomized subjects were mainly related to the surgery.

Outcome categories were formed on the basis of pre- and postoperative scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, as described by Jenike et al. (

5). Marked improvement (>75%) was shown by 44% of the subjects (N=7), and another 25% (N=4) showed moderate improvement (>50%). Only one subject (6%) experienced less than 25% improvement in obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Eleven (85%) of the 13 subjects with OCD but not obsessive personality disorder were convinced that the surgery was the cause for all or most of their improvement, which appeared in eight subjects 3–12 months after surgery and in three subjects 1–2 years postoperatively. Two of the subjects with both OCD and obsessive personality disorder experienced less intense improvement 3–8 months postoperatively, and one subject with OCD and obsessive personality disorder experienced no operation effect.

Table 4 contains the rates of improvement for the 16 leukotomized study subjects and for the contacted subjects who did not receive neuropsychological examinations. The OCD subjects completing only questionnaires showed strong improvements (86%) (Wilcoxon test: z=–2.4, p<0.02) on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale similar to those of the study subjects (82%) (z=–3.2, p<0.01). The self-ratings of outcome on the visual analogue scale were similar for the study subjects, the subjects completing only questionnaires, and the subjects not available for these kinds of evaluation (

table 4). The improvement reported by self-rating was significantly related to the improvement in Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale scores for the study subjects (r

s=0.68, N=16, p<0.005) and for the subjects completing only questionnaires (r

s=0.68, N=13, p<0.01).

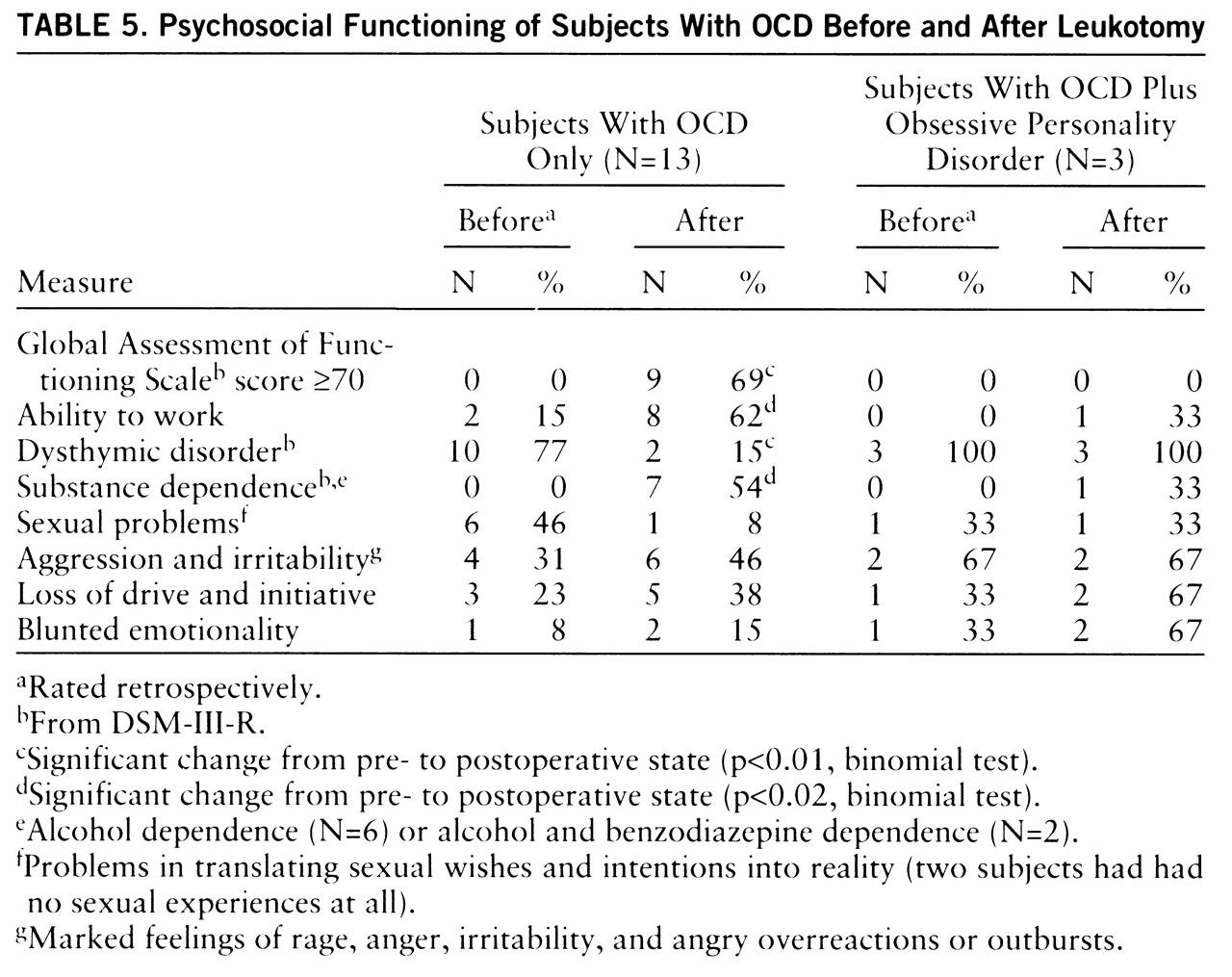

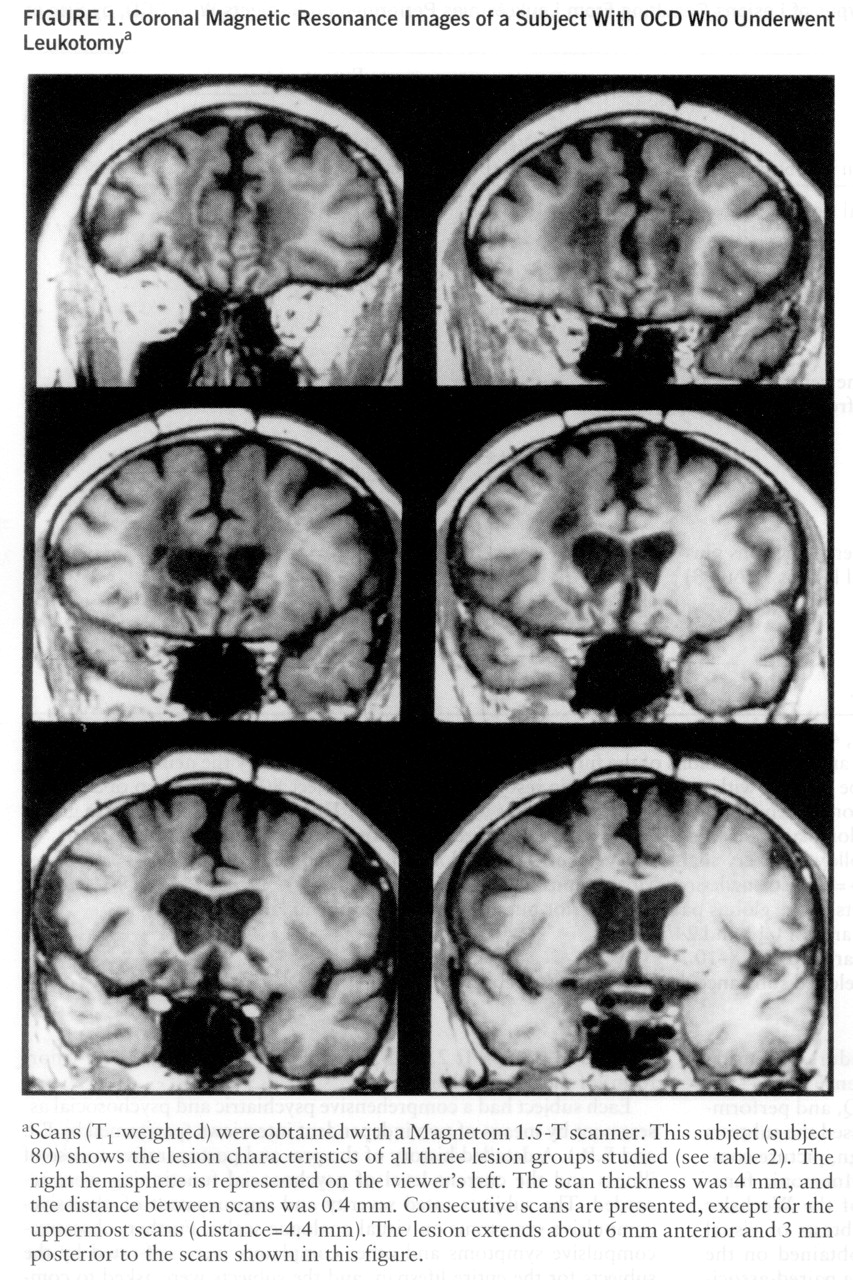

Changes on measures of psychosocial functioning can be seen from

table 5. The postoperative scores of the OCD subjects on the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (axis V of DSM-III-R) were significantly better than the preoperative scores (determined retrospectively). Further, there was a significant increase after surgery in the number of OCD subjects who were able to work. Also, significantly fewer OCD subjects suffered from dysthymic disorder after leukotomy. Sexual problems were reduced postoperatively in five of the seven subjects complaining of them preoperatively. However, for three subjects (numbers 32, 56, and 59) a loss of drive and initiative clearly occurred after surgery. These subjects, as well as those with combined OCD and obsessive personality disorder, also had higher depression scores (t value >70) on the MMPI after surgery.

There was a significant increase in the number of subjects who became addicted to alcohol (N=6) or to alcohol and benzodiazepines (N=2) after psychosurgery, and there was no case of substance dependence before surgery (

table 5). The addicted subjects started to drink between 3 and 9 years postoperatively and in most cases during severe psychosocial stress (e.g., divorce, accident). Five of these subjects experienced remissions of their substance dependence during long-term inpatient psychotherapy. The remaining three subjects (numbers 10, 56, and 59) had extraordinarily severe courses of chronic alcohol disorder, being refractory to numerous and protracted inpatient psychotherapies. Subjects 56 and 77 had family histories of alcoholism and had occasionally showed signs of substance abuse before psychosurgery.

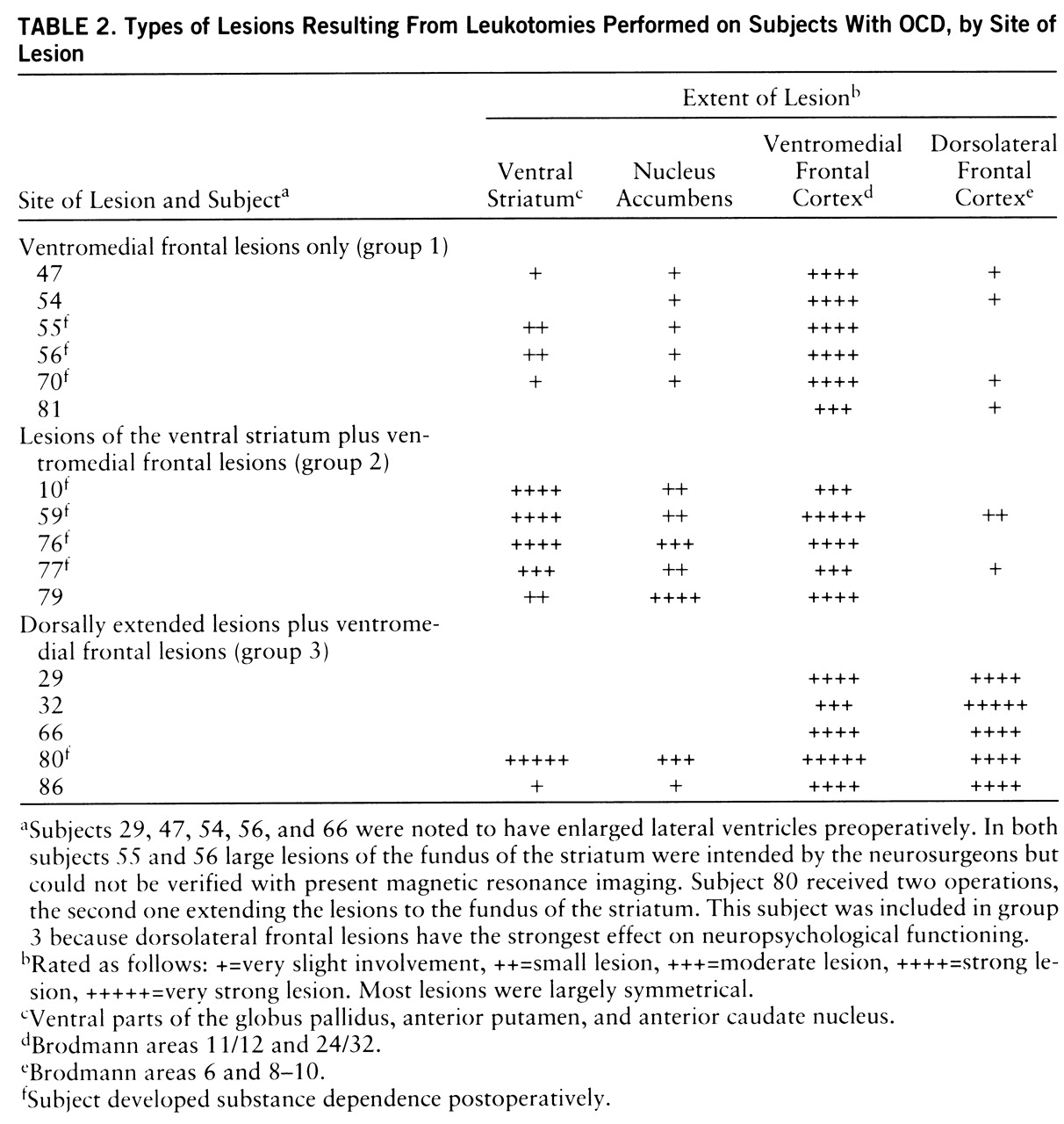

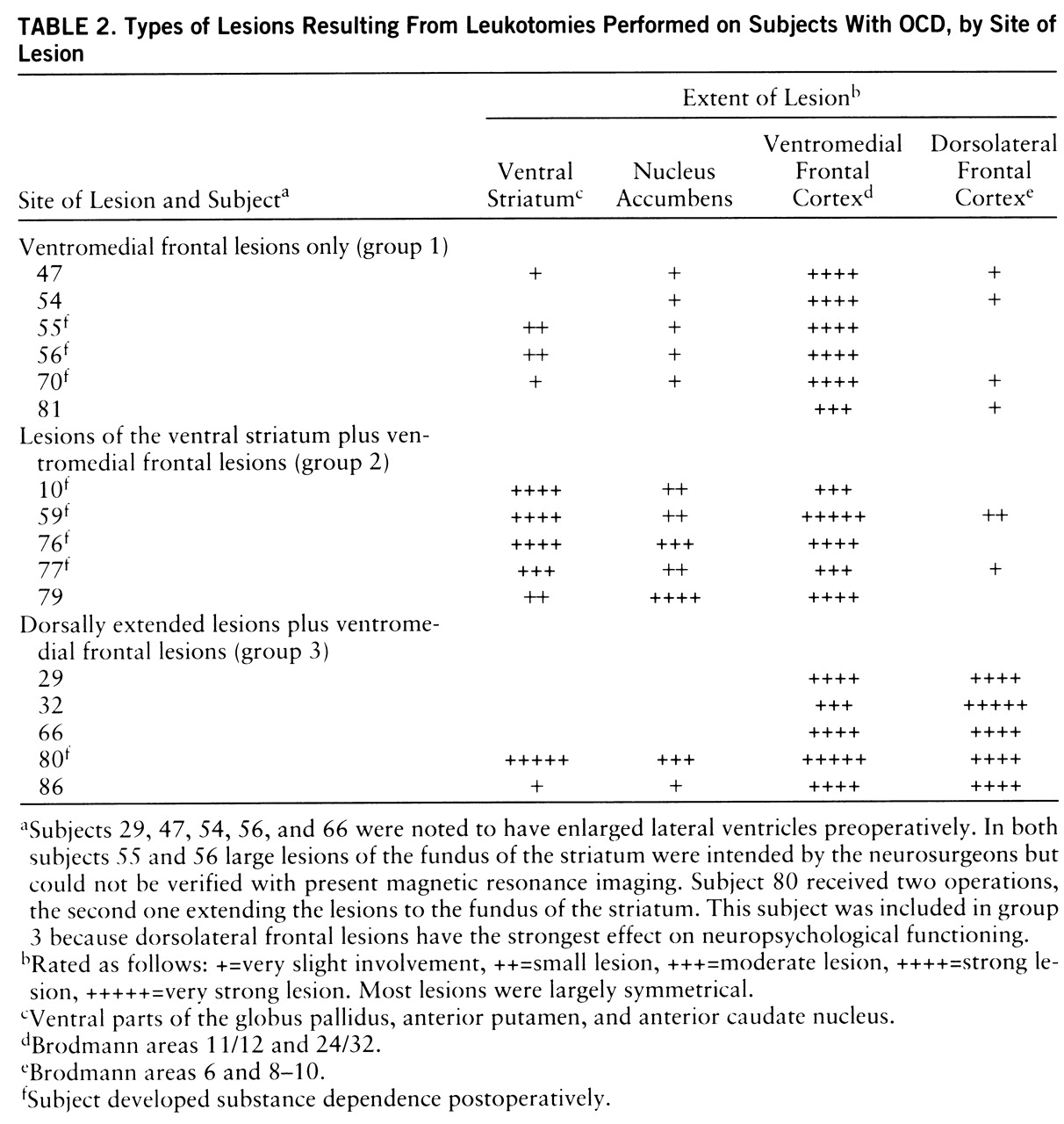

Lesion analysis revealed that all of the addicted subjects had lesions in the ventral striatum. Of the 11 subjects with lesions of the ventral striatum (

table 2), eight developed substance dependence postoperatively (p<0.01, binomial test). There was no case of postoperative addiction in the subjects without striatal lesions. Accordingly, the extent of ventral striatal lesions (as indicated in

table 2) was significantly different for the addicted and nonaddicted subjects (U=3.0, p<0.002).