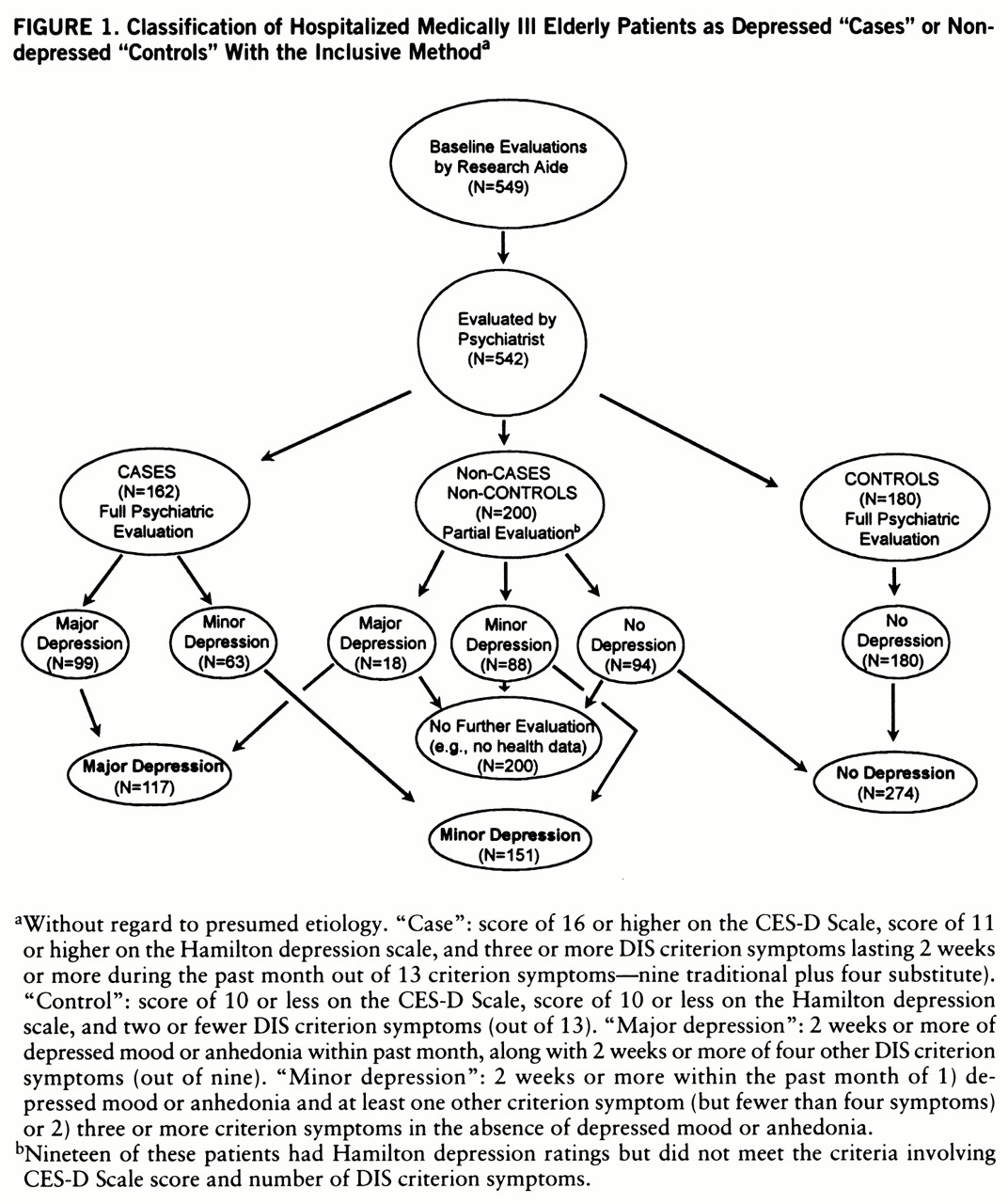

The research assistant completed baseline evaluations of 549 patients; of these, 542 patients (79.4% of the 683 eligible patients) were evaluated within 24 hours by the psychiatrist. The reasons for nonparticipation were failure to complete the psychiatric evaluation (N=7), refusal (N=26), prevention of interview by family, nurse, or house staff (N=74), and miscellaneous reasons (N=34). There was no significant difference between the participants (N=542) and nonparticipants (N=141) in terms of race, sex, insurance status, admitting service, or admitting medical diagnosis. The nonparticipants were older (mean age, 72.9 versus 70.2 years) and seen later in the hospital stay (mean, day 5.1 versus day 4.5) than were the participants. We compared the demographic characteristics of the 542 patients in our study group with those of the general population, on the basis of data collected from a random sample of 4,000 adults aged 65 or over living in central North Carolina (

22). The percentages of women in our study group and in the general population were 51.8% and 62.6%, respectively; the percentages of black persons were 32.5% and 35.5%; and the percentages with at least 12 years of education were 42.6% and 29.0%.

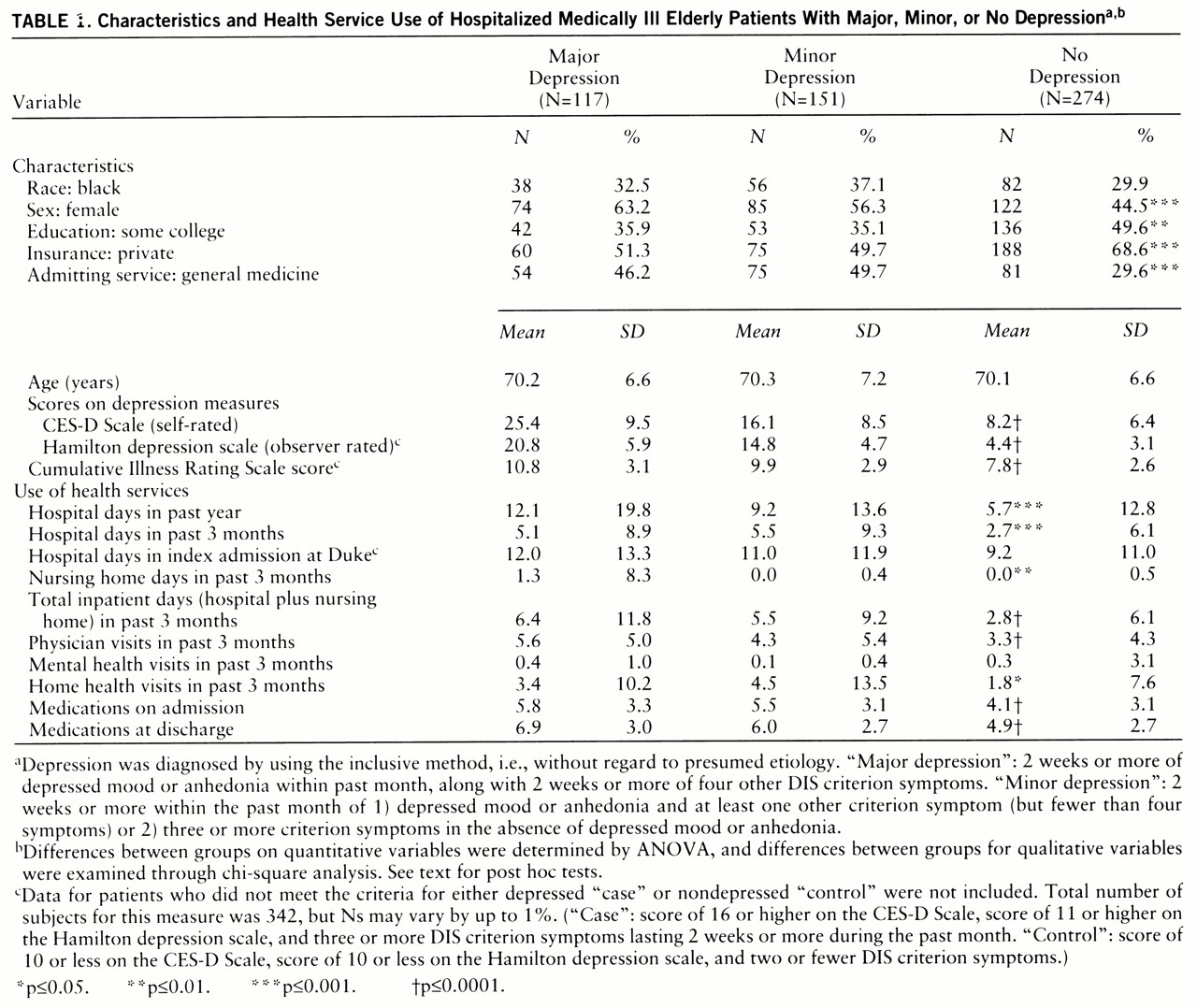

Bivariate Correlational Analyses

Measures of both outpatient and inpatient health service use were significantly correlated with depressive symptoms, whether determined by the self-rated CES-D Scale or by the psychiatrist-rated Hamilton depression scale. The CES-D Scale score was related to days of hospitalization in the past year (r=0.15, N=542, p=0.0003), length of index hospital stay (r=0.10, N=340, p=0.06), and total inpatient days within the past 3 months (r=0.09, N=542, p=0.04). CES-D Scale score was also related to number of physician visits within the past 3 months (r=0.14, N=542, p=0.001) and number of prescription medications taken on admission (r=0.22, N=339, p<0.0001) and at discharge (r=0.26, N=339, p<0.0001). CES-D Scale score was unrelated to short-stay hospital days, nursing home days, home health visits, and visits to mental health providers in the past 3 months.

Likewise, the score on the Hamilton depression scale was significantly related to number of short-stay hospital days in the past year (r=0.32, N=361, p<0.0001), short-stay hospital days in the past 3 months (r=0.21, N=361, p<0.0001), length of index hospital stay (r=0.12, N=340, p=0.02), number of nursing home days in the past 3 months (r=0.13, N=361, p=0.02), and total inpatient hospital days in the past 3 months (r=0.24, N=361, p<0.0001). Hamilton depression score was also related to number of physician visits (r=0.24, N=361, p<0.0001), home health visits (r=0.15, N=361, p=0.006), and number of prescription medications taken on admission (r=0.29, N=339, p<0.0001) and at discharge (r=0.33, N=339, p<0.0001). Like the CES-D Scale score, the Hamilton depression score was unrelated to number of visits to mental health providers in the past 3 months.

Multiple Regression Analyses

Controlling for age, gender, race, education, and severity of illness, we conducted polynomial regressions to determine the association between health service use and depression variables along with second-order terms of age and severity of medical illness. The polynomial regressions did not show the significance of the second-order terms, and so all of the regressions were carried out without controls for the quadratic effects of these two variables.

Among the case and control subjects (N=341), multiple regression analyses continued to reveal associations between depression and service use after the covariates were controlled. Depressive symptoms (Hamilton depression score) continued to predict number of short-stay hospital days within the past year (t=3.5, df=1, p=0.0005; model R2=0.15, F=9.8, df=6,334) and numbers of short-stay hospital days (t=2.0, df=1, p=0.05; model R2=0.05, F=3.1, df=6,334), nursing home days (t=1.9, df=1, p=0.06; model R2=0.04, F=2.1, df=6,334), and total inpatient days within the past 3 months (t=2.8, df=1, p=0.005; model R2=0.10, F=6.0, df=6,334). Depressive symptoms also continued to predict number of outpatient physician visits (t=2.8, df=1, p=0.007; model R2=0.09, F=5.6, df=6,334). Associations between depressive symptoms and length of index hospital stay, home health visits, nursing home days, and prescription medications all disappeared once severity of medical illness was controlled.

The bivariate analyses described earlier revealed that the patients with major and minor depression were more similar to each other than to patients without depression. Therefore, for the multivariate regression models we combined the patients with major and minor depression (N=161) and compared them to the patients without depression (N=180). Patients thus categorized as depressed by the “inclusive” approach had more total inpatient days (hospital and nursing home) (t=2.2, df=1, p=0.03; model R2=0.09, F=5.4, df=6,334) and more medical outpatient visits (t=3.2, df=1, p=0.002; model R2=0.10, F=6.1, df=6,334) in the past 3 months than did nondepressed patients. There was also a tendency for depressed patients to have more short-stay hospital days in the past year (t=1.8, df=1, p=0.07; model R2=0.13, F=8.1, df=6,334) and in the past 3 months (t=1.9, df=1, p=0.06; model R2=0.05, F=3.0, df=6,334). There was no association, however, between depressive disorder and length of index hospital stay, nursing home days, home health visits, mental health visits, or prescription medications.

When the DSM-IV “etiologic” approach for diagnosing depression was used, the results were largely similar. The depressed patients had more short-stay hospital days in the past year (t=2.0, df=1, p=0.05; model R2=0.13, F=8.2, df=6,334) and more short-stay hospital days (t=2.1, df=1, p=0.04; model R2=0.05, F=3.1, df=6,334), more total inpatient days (t=2.5, df=1, p=0.01; model R2=0.09, F=5.7, df=6,334), and more physician visits (t=1.9, df=1, p=0.06; model R2=0.08, F=4.9, df=6,334) in the past 3 months.

No depressed patients were admitted to psychiatric hospitals during the 3 months before admission. Outpatient visits to mental health professionals (psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers) were also no more common among the depressed than nondepressed patients.