Subject Recruitment and Data Collection

We conducted first-stage screening for current depression by using a 0.06 cutoff on the previously validated Burnam screener (

4) during telephone interviews in 1992–1993 with randomly selected adults aged 18 years and over in 11,078 (70.5%) of 15,721 randomly selected Arkansas households with listed and unlisted telephone numbers. In order to address the aims of the original study, we used a stratified sampling design to oversample nonmetropolitan counties. Of the 11,078 screened household members, 998 (9.0%) screened positive for current depression. We excluded 286 bereaved, 54 manic, and 14 acutely suicidal subjects and eight individuals who denied all depressive symptoms at the baseline interview, and 470 (73.9%) of the 636 remaining depressed adults agreed to participate in a 3-hour, face-to-face baseline interview, which most subjects completed with~in 1 month after the telephone interview. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. The participants were similar to the nonparticipants in all socio~demographic and clinical characteristics (including depression severity) except age and residence. The participants were significantly younger—the mean ages of the participants and nonparticipants were 46.3 (SD=15.8) and 55.1 (SD=18.7) years (two-tailed t test: t=5.34, df=253, p<0.0001)—and more likely to reside in metropolitan areas (25.7% versus 16.9%) (χ

2=5.39, df=1, p<0.02) than nonparticipants. Of the 470 subjects, 336 (71.5%) met the criteria for lifetime major depression with current symptoms during the baseline interview. We chose to eliminate subjects who screened positive without meeting the criteria for lifetime major depression because too few sought services to make reliable expenditure estimates.

Adapting previously validated questions from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study (

5), we conducted telephone interviews with 318 (94.6%) of the original 336 subjects 6 and 12 months after baseline to identify all hospitals, emergency rooms, outpatient care settings, and pharmacies that had provided professional health services for physical or emotional problems to each subject during the previous 6 months. With the subject's written permission after full explanation of the procedures, we requested complete medical and billing records from these providers. We reviewed these records in conjunction with the subject's insurance records in order to identify additional providers whom the subject had failed to recall. We contacted all providers repeatedly by writing, by telephone, or in person until complete medical and billing records were obtained. Using this method, we obtained complete billing records on 311 (97.8%) of the 318 subjects completing both the 6- and 12-month interviews. Records were determined to be complete when all relevant utilization and billing information was obtained from the subject's insurer and/or provider. Finally, we excluded 13 subjects in managed care health plans, leaving 298 subjects who are included in this analysis.

Operational Definitions of Major Constructs

Using the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) for DSM-III-R (

6) and the Inventory to Diagnose Depression (

7), which were administered during the baseline interview, we categorized eligible subjects as having 1) major depression—defined as being at or above the cutpoint on the depression screen, a lifetime diagnosis of major depression on the DIS, and five or more symptoms in the last 2 weeks according to the Inventory to Diagnose Depression—or 2) subthreshold major depression—defined as being at or above the cutpoint on the depression screen, a lifetime diagnosis of major depression, and four or fewer symptoms in the last 2 weeks.

All expenditure estimates in this study and those reported from previous studies were expressed in 1994 dollars by using the medical care component of the consumer price index (

8).

A hospitalization was defined as an admission to a health care facility that resulted in an overnight stay. A hospitalization was defined as depression treatment if 1) depression was coded as a diagnosis or noted as a symptom in the medical or billing record, 2) the subject received an antidepressant medication during the hospitalization, or 3) the subject noted the hospitalization was for depression.

An outpatient visit was defined as a visit to a medical doctor, osteopath, nurse practitioner, physician's assistant, or mental health professional in an office, clinic, or emergency room that did not result in an overnight stay. Outpatient visits were defined as depression treatment by using criteria parallel to those regarding hospitalization. Because psychotherapy delivered for other mental health diagnoses may potentially benefit co-occurring depression, we excluded a total of $3,384 for psychotherapy services delivered for diagnoses other than depression in this sample. We reasoned that the additional $24 per capita ($3,384/143) that this amount would add to our estimate of depression expenditures for the treated group would not materially change the major findings of this paper, and we elected to use the preceding definition to maintain consistency with previous publications (

9).

The expenditures for outpatient depression treatment were categorized as provider services, prescriptions, or laboratory tests. Provider services included diagnosis, management (pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy), and monitoring. Prescription services included all antidepressant medications listed in recently released guidelines (

10) and concomitantly prescribed minor tranquilizers. Laboratory tests included thyroid panel tests (except in cases where thyroid tests were administered to subjects with established thyroid diagnoses), reflecting the emphasis in published guidelines (

11) on avoiding unnecessary tests to rule out other physical conditions before making the diagnosis of major depression.

For admissions, visits, or procedures involving multiple diagnoses, the psychiatrist raters used a detailed protocol to identify which expenditures were related to depression. This protocol is available from the authors on request.

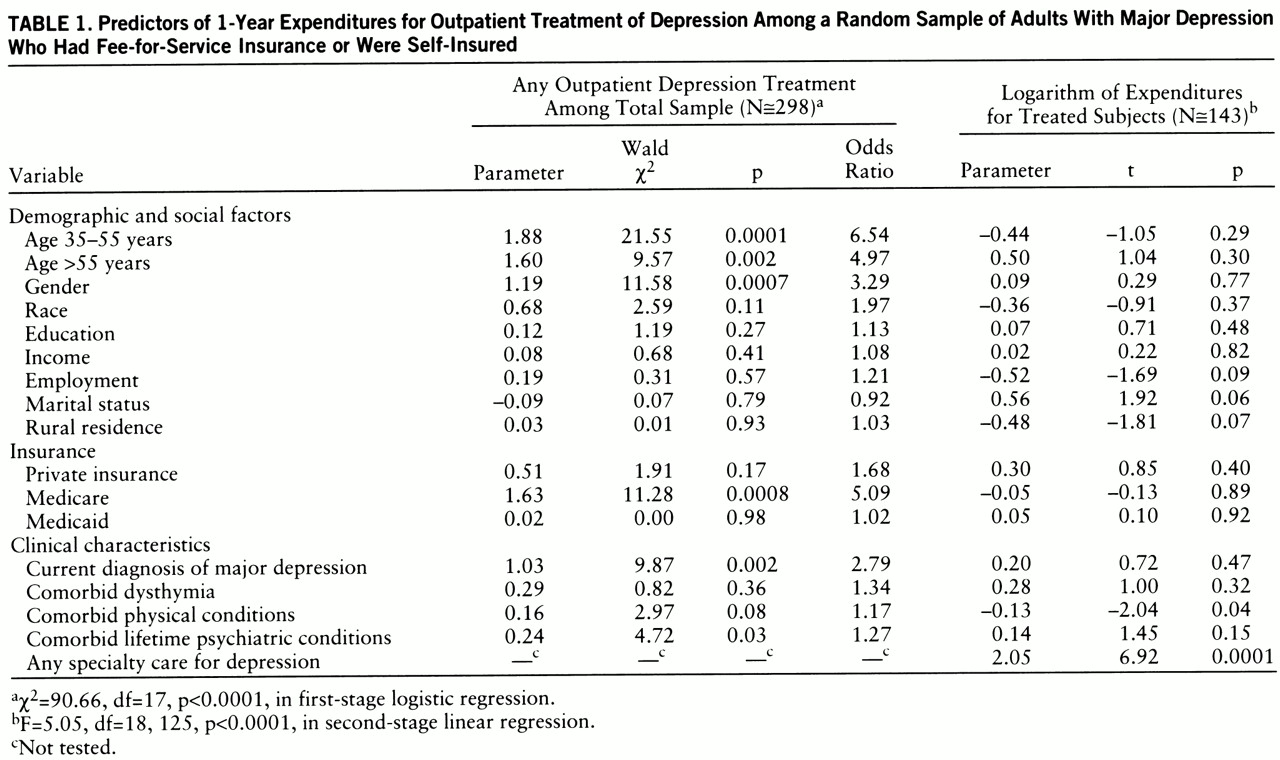

The clinical predictors determined at baseline were major depression diagnosis (major depression, subthreshold major depression), dysthymia, psychiatric comorbidity, physical comorbidity, and previous psychiatric hospitalization. Depressive diagnosis and previous psychiatric hospitalization were determined by using the DIS (

6). Psychiatric comorbidity was defined as the number of eight nonaffective lifetime psychiatric diagnoses present according to the Quick Diagnostic Interview Schedule (

12). Physical comorbidity was the number of 12 chronic physical problems the subject reported. The nonclinical predictors determined at baseline were age, gender, race, education, income (ratio of the household income to the poverty line adjusted for family size), employment, marital status, residence in a nonmetropolitan statistical area, and health insurance (categorized from billing records as private, Medicare, Medicaid, or uninsured).

Outpatient visits were categorized as specialty care if the provider was a psychiatrist, psychologist, psychological examiner, social worker, or counselor. They were classified as general medical care if the provider was other than a mental health professional, such as an internist, family physician, or general practitioner.

Similar to the procedure in the National Medical Expenditure Survey (

13), total health care expenditures were defined as all charges for inpatient hospital and physician services, outpatient physician and nonphysician services, and prescription medications. Optometry and dental charges were estimated in the National Medical Expenditure Survey, but that information was not collected in this study.