We recruited 80 subjects into the study over a 7-year period, beginning in March 1991 and concluding in February 1998. Recruitment for this study was difficult and labor-intensive, as we recently detailed in a description of our methods of recruitment (

14). Briefly, most subjects were self-referred in response to print advertisements or letters sent from the investigators to surviving spouses identified in obituaries. Relatively few patients were clinically referred.

To be included in the study, potential subjects were required to meet the criteria of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L) (

15) and the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (

16) for a definite current major depressive episode (nonpsychotic and nonbipolar, with no history of chronic intermittent depression or dysthymia). Forty-eight subjects were diagnosed with the SADS-L and 32 with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (

17), which replaced the SADS-L as our primary diagnostic instrument in 1996. The onset of the episode was required to fall in the period between 6 months before the death of the spouse and 12 months after the death. Episodes could be either single or recurrent. No other diagnoses, with the exception of generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder, were allowed. Diagnostic reliability was ensured through the use of a structured diagnostic assessment together with independent clinical confirmation by a senior psychiatrist (M.D.M., R.E.P.). A bereavement intensity score of 45 or more on the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief (

18) was required as an indication of active grieving. Finally, to be eligible for the study, subjects were required to provide written informed consent. The recruitment, assessment, and treatment protocols were approved by our biomedical institutional review board.

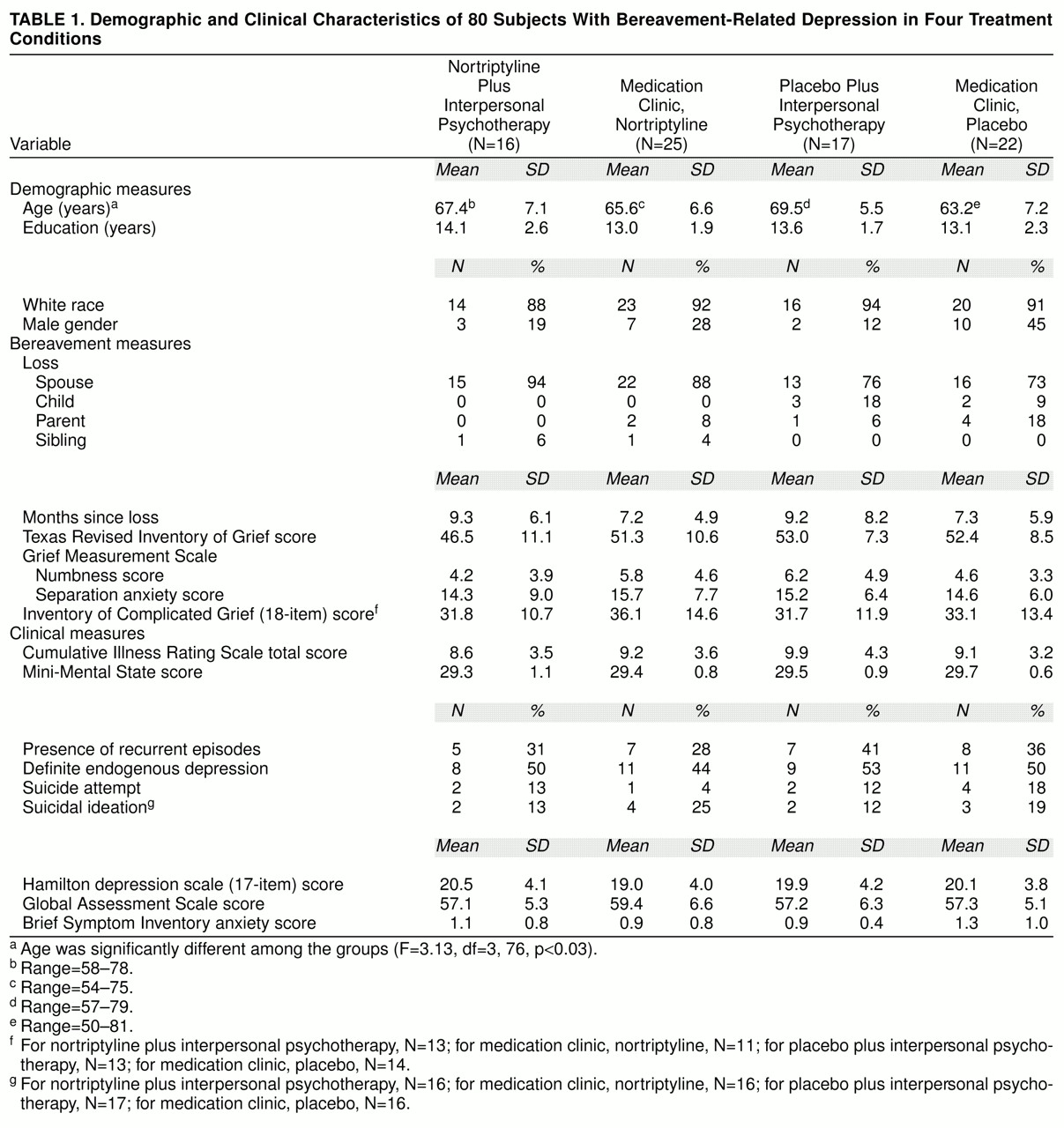

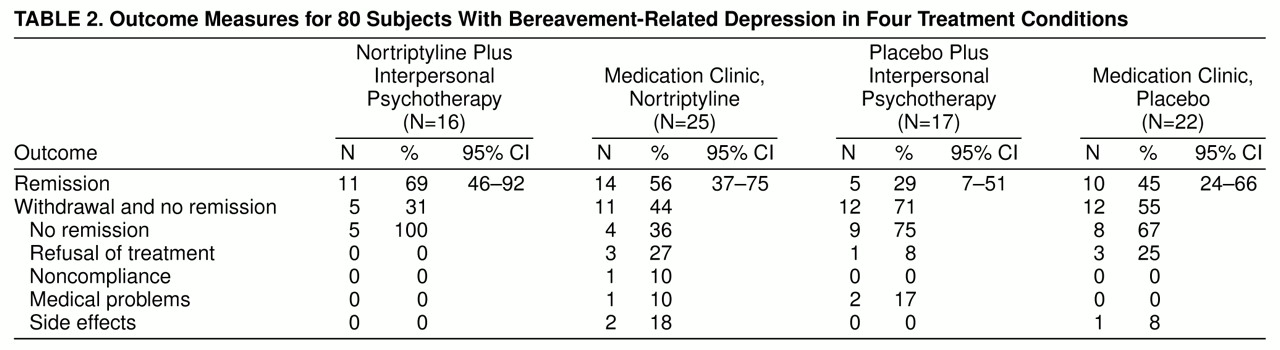

As shown in

table 1, subjects were randomly assigned to one of our treatment groups: 1) nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy, 2) nortriptyline in a medication clinic, 3) placebo and interpersonal psychotherapy, or 4) placebo in a medication clinic. Most subjects were white female outpatients with mild to moderate episodes of major depression and some associated functional impairment. Most were in their 60s; however, the group randomly assigned to medication clinic, placebo, was significantly younger than the other groups. About two-thirds of the total study group reported that they were in their first lifetime episode of major depression, and a substantial minority reported either suicidal ideation (17%) or a history of suicide attempts (11%). About one-half the study group met the RDC or DSM-IV criteria for definitely endogenous or melancholic episodes. Typically, subjects had lost a spouse or significant other 7–9 months earlier (median=32 weeks, with no difference between treatment groups). The treatment groups did not differ significantly on measures of bereavement intensity (Texas Revised Inventory of Grief [

18], Grief Measurement Scale [(

19], [

20], [ and Inventory of Complicated Grief

21]). There was also no significant difference in depression severity (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [

22]), cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental State [

23]), or the Brief Symptom Inventory (

24) measure of anxiety. Because the groups differed in age, as noted above, age was used as a covariate in the major outcome analysis. The distribution of all other demographic, bereavement, and clinical measures was equal among the groups.

The numbers of subjects in the four treatment conditions differ because we enlarged the scope of the study from a two-cell design initially (nortriptyline versus placebo) to the current four-cell design 2 years after beginning recruitment. Sixteen subjects were recruited into the original two-cell study and 64 into the four-cell study. Pretreatment Hamilton depression ratings averaged 18 among subjects in the two-cell study and 20 among subjects in the four-cell study (nonsignificant difference). We added a psychotherapy condition because our pilot data had suggested that antidepressant medication did not lessen the intensity of bereavement (

25) and because of the clinical need to develop effective interventions for elderly patients who either cannot or will not take antidepressant medication. In this context, we adopted the current 2 × 2 factorial design as a test of both the main effects of the drug and psychotherapy and their hypothesized interaction on the resolution of bereavement-related major depression.

Treatment Design, Rationale, and Integrity

After baseline evaluation, including a 14-day psychotropic-drug-free observation period to ensure stability of symptom severity, patients were randomly assigned to treatment in one of four cells, stratified by the presence of single versus recurrent episodes of major depression: 1) medication clinic, nortriptyline, 2) medication clinic, placebo, 3) interpersonal psychotherapy plus nortriptyline, and 4) interpersonal psychotherapy plus placebo. Both subjects and treating clinicians were kept blind to placebo or nortriptyline assignment. Procedures for the implementation of medication clinic treatment and for interpersonal psychotherapy followed manuals developed by the investigators (available on request from the first author). Nortriptyline and placebo tablets were of identical size (9 mm in diameter), weight (250 mg), and appearance. They were prepared by research pharmacist Dr. Umesh Banakar and certified for content by one of us (J.M.P.) under Food and Drug Administration IND 37603 to J.M.P (sponsor) and to C.F.R. (investigator).

At the time we were developing this study in 1990–1991, we chose nortriptyline for two reasons: 1) our literature review for the Agency on Health Care Policy and Research’s Depression Panel Guideline Report on the treatment of geriatric depression concluded that the then-available database supporting the efficacy of nortriptyline was the best for any antidepressant at that time (

26), and 2) our open pilot work with nortriptyline in bereavement-related depression supported its efficacy and safety (

25) as well as its favorable side effects profile (

27). Similarly, we chose interpersonal psychotherapy because, as originally developed by Klerman et al. (

13), it included a specific focus on bereavement. In addition, in our recently completed study of nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy in the maintenance therapies of late-life depression (

28), we had found that interpersonal psychotherapy could be combined with a tablet (either placebo or nortriptyline), was “user-friendly” for elderly depressed patients (especially in the hands of experienced therapists), and was clinically relevant to the complex task of helping older patients adjust to the loss of a spouse.

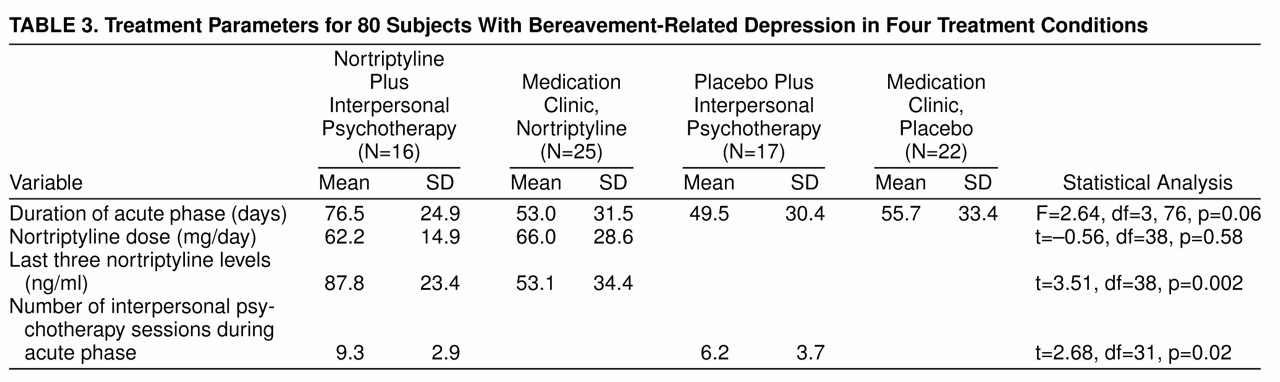

Patients assigned to a medication clinic condition were seen weekly during the acute treatment phase by the same two clinicians, one of whom was a co-investigator psychiatrist (R.E.P.) blind to treatment assignment (nortriptyline or placebo). The same clinicians provided either medication clinic treatment or interpersonal psychotherapy, depending on random assignment. All patients received symptom and side effect evaluations and education about depression as a medical illness. Patients in the medication clinic condition received no specific psychotherapy. The starting dose of nortriptyline was 25 mg h.s. for the first week, increased in 25-mg increments each week thereafter on the basis of clinical and blood level data. Blood samples for ascertaining nortriptyline levels were drawn at each visit, which lasted about 30 minutes weekly. Plasma nortriptyline levels were determined in the laboratory of the psychopharmacologist co-investigator (J.M.P.) with the use of previously published methods of high-performance liquid chromatography (

29). All treatment visits, regardless of medication clinic or psychotherapy assignment, included orthostatic pulse and blood pressure readings, weight determination, and clinical evaluations and ratings (Hamilton depression scale, Beck Depression Inventory, Global Assessment Scale [

30], and Asberg side effect rating scale [

31]). These data were reviewed weekly by a nonblind monitoring committee consisting of the principal investigator (C.F.R.) and a co-investigator (M.D.M.). This committee adjusted the dose of nortriptyline to ensure a steady-state plasma level of at least 50 ng/ml but no more than 120 ng/ml. The measure of grief intensity, the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief, was administered monthly.

For the patients assigned to interpersonal psychotherapy, the treatment was delivered weekly during 50-minute sessions by experienced clinicians (two masters of social work, one master of education, and one doctoral-level clinical psychologist). The psychotherapists were trained to and maintained at research levels of proficiency in interpersonal psychotherapy by two of the co-investigators (E.F. and C.C.). These same clinicians also provided medication clinic treatment to the patients randomly assigned to the medication clinic.

All medication clinic and interpersonal psychotherapy sessions were audiotaped for rating of elements specific to the interpersonal psychotherapy and medication clinic conditions, in order to ensure treatment integrity and compliance with manual-based treatment delivery procedures. In previous analyses of rating scale factor scores (interpersonal psychotherapy or medication clinic), for interpersonal psychotherapy sessions each clinician-therapist demonstrated higher interpersonal psychotherapy factor scores than medication clinic scores. Conversely, for medication clinic sessions, every clinician-therapist demonstrated higher medication clinic factor scores than interpersonal psychotherapy factor scores. In discriminant function analyses using factor scores, we have consistently obtained significant discriminations, with over 80% of interpersonal psychotherapy sessions and medication clinic sessions being accurately classified (

32). These data demonstrate that project clinicians were able to deliver interpersonal psychotherapy to bereaved depressed persons in a way that could be discriminated from medication clinic treatment by blind raters. We monitored compliance with pharmacotherapy both behaviorally (e.g., through education of patients and family members, pharmacy pill counts, and weekly reminders and checks) and pharmacologically (e.g., by examination of nortriptyline blood levels over time).

Subjects who achieved remission of symptoms (a 17-item Hamilton depression scale score of 7 or lower for 3 consecutive weeks) entered into continuation therapy (also double-blind) for an additional 16 weeks, to ensure stability of clinical response. Subjects who did not achieve at least a 50% reduction in Hamilton depression score by week 8 of double-blind treatment were deemed to be nonresponders and were treated openly. After continuation treatment, subjects were gradually withdrawn from treatment over 6 weeks and followed up for 2 years, to assess the stability of their response to treatment. We maintain an interrater reliability of no more than 2 points’ difference in total ratings on the Hamilton depression scale.

We used a generalized logit model to test the difference in remission rates between treatment groups (

33). Maximum likelihood estimates of the main effect parameters of nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy and of their interaction were derived and tested with Wald chi-square statistics (

34). Age was used as a covariate.