The diagnostic categories of DSM-IV attempt to reflect “a consensus of current formulations of evolving knowledge in our field” (p. xxvii). Some diagnoses, such as premenstrual dysphoric disorder and binge eating disorder, do not meet DSM-IV standards for consensus and appear only as proposed diagnoses in appendix B (p. 703). But other diagnoses, including dissociative amnesia and dissociative identity disorder, attained official status in DSM-IV despite apparent controversy

(1, 2). The official recognition of these diagnoses in DSM-IV is cited by some

(3) as evidence that they are generally accepted within the field. What is the actual degree of consensus regarding dissociative amnesia and dissociative identity disorder today? To address this question, we surveyed a random national sample of board-certified American psychiatrists.

METHOD

We began by consulting the 1995 edition of

The Official ABMS Directory of Board-Certified Medical Specialists (

4), which contains more than 400 pages listing board-certified general psychiatrists alphabetically by state. We mailed a questionnaire, described later, to one psychiatrist on each page, who was selected by a prescribed formula (omitted here to preserve respondents’ confidentiality). American psychiatrists practicing outside of the 50 states were excluded. Retired psychiatrists and psychiatrists with incomplete biographical information were replaced with the next available name. Individuals who failed to respond were sent second and third requests, the last by certified mail.

If a questionnaire was returned as undeliverable, we sought the individual’s updated address in the 1998 edition of the directory. If the new address was in the same state, we mailed the questionnaire to the new address. If the individual had left the state or lacked a new address, we mailed the questionnaire to the next psychiatrist in that state, who met the previously described criteria, from the corresponding page of the 1998 directory. Some of these letters, in turn, were returned as undeliverable; we replaced these individuals by the same method.

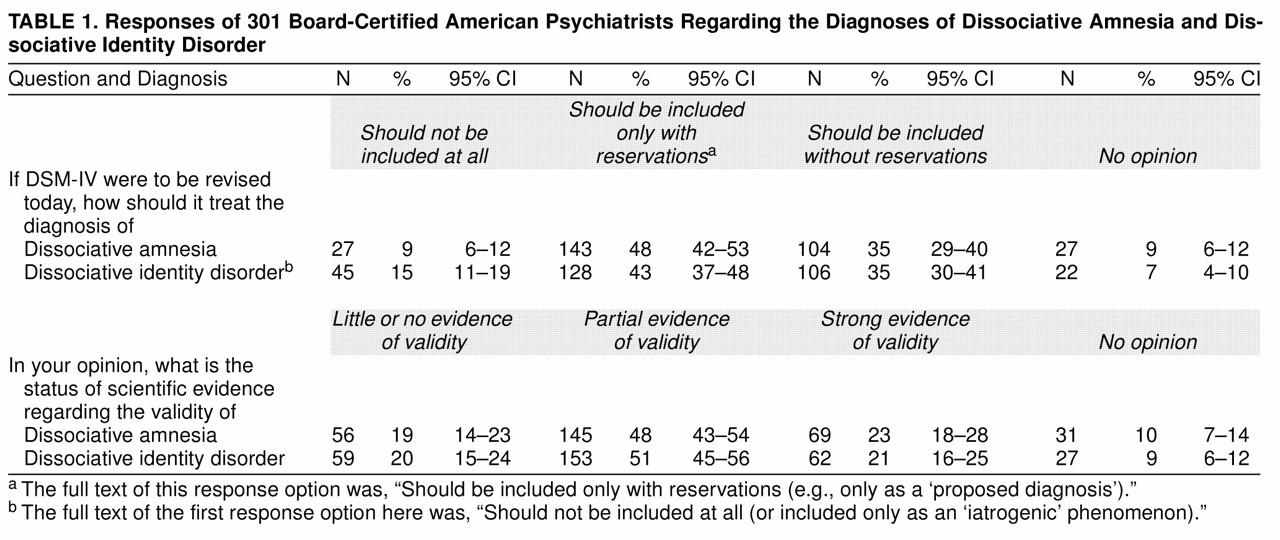

The one-page questionnaire asked the respondent’s principal professional activities, ranked by time spent; theoretical orientation; and authorship on published papers. The remaining four questions, shown in

table 1, asked the respondent’s opinions regarding the diagnostic status and scientific validity of dissociative amnesia and dissociative identity disorder. The accompanying cover letter was signed by only one investigator (A.J.G.) because she had published no papers related to dissociative disorders and was unknown to most respondents. We used the generic letterhead of McLean Hospital, a large institution including psychiatrists with diverse views, to further minimize response bias.

RESULTS

Of 406 questionnaires initially sent, 36 were returned as undeliverable despite two rounds of replacement. No receipt was received on three other questionnaires sent on the third round by certified mail. Thus, 367 psychiatrists actually received a questionnaire. Of these, 301 responded—a rate of 82%. The 1998 directory showed that 219 (73%) of these were men, 165 (55%) were at least 50 years old, 261 (87%) were members of APA, and 193 (64%) held an academic appointment. Five respondents left the first three questions blank. Of the rest, 248 (84%) listed their principal activity as patient care, nine (3%) as research, seven (2%) as teaching, 28 (10%) as administration, and four (1%) as other. In addition, 119 (40%) rated their theoretical orientation as psychodynamic-psychoanalytic, 123 (41%) as biological, eight (3%) as cognitive-behavioral, and 46 (16%) as other. (On these questions, respondents who gave equal rank to two or more categories were classified as “other.”) Finally, 136 (46%) reported having published no scientific papers, 106 (36%) one to nine papers, and 54 (18%) 10 or more papers.

In response to the questions about dissociative amnesia and dissociative identity disorder (

table 1), only about a third of respondents replied that these diagnoses should be included without reservations in DSM-IV; the modal response was that they should be included only as proposed diagnoses. Respondents also showed little consensus on the scientific validity of dissociative amnesia and dissociative identity disorder.

We performed logistic regression to assess the association (by using the likelihood ratio test) between acceptance of dissociative amnesia or dissociative identity disorder (favoring inclusion of the diagnoses without reservations or claiming strong evidence of validity) and gender, age (45 or younger, 46–54, and 55 or older), APA membership, an academic appointment, principal activity (patient care versus all others), theoretical orientation (psychodynamic versus biological versus other), and publications (none versus any). None of these univariate associations approached statistical significance, except those involving theoretical orientation. Psychodynamic psychiatrists were more likely than biological psychiatrists to reply that dissociative amnesia should be included in DSM-IV without reservations (44% versus 30%) (Wald test χ2=4.23, df=1, p=0.04), that dissociative amnesia was supported by strong evidence (31% versus 20%) (χ2=3.93, df=1, p=0.05), that dissociative identity disorder should be included in DSM-IV without reservations (46% versus 28%) (χ2=6.97, df=1, p=0.008), and that dissociative identity disorder was supported by strong evidence (32% versus 14%) (χ2=9.40, df=1, p=0.002). The responses of the “other” group were primarily intermediate between those of the psychodynamic and biological psychiatrists; there were no significant differences (p>0.05) between the other group and either psychodynamic or biological psychiatrists.

We also used step-up and step-down multivariate procedures to assess which combination of the predictor variables yielded the most parsimonious model. Both procedures kept only theoretical orientation in the final model, suggesting that the results of the univariate analyses presented earlier were not influenced in any important ways by the other predictor variables.

DISCUSSION

We sought to assess current opinion regarding the nosological status and scientific validity of dissociative amnesia and dissociative identity disorder in a national sample of board-certified American psychiatrists. In this group, we found little consensus on these issues. In an analysis of the attributes of respondents, only theoretical orientation appeared significantly associated with acceptance of dissociative disorders; psychodynamic psychiatrists were more likely than biological psychiatrists to endorse dissociative amnesia and dissociative identity disorder.

We should consider several methodological issues. First, serious bias seems unlikely, since our methods would be expected to yield a random sample of board-certified psychiatrists. In addition, given the high response rate of 82%, even possible differences in attitudes among nonresponders would only modestly change the results. Second, the findings are unlikely due to chance, as evidenced by the 95% confidence intervals shown in table 1.

Finally, there is the question of whether board-certified American psychiatrists represent an appropriate source population for judging consensus. On the one hand, it might be suggested that our population is too narrow and should include all psychiatrists or even all mental health professionals. For example, one study

(5) surveyed a range of professionals, from clinical social workers to Ph.D. psychologists (but not psychiatrists), and found a similar divergence of views on dissociative disorders. An earlier study

(6) found that 75% of Veterans Administration psychiatrists and 83% of psychologists “believed in” multiple personality disorder, but the response rate in that survey was only 31%, raising the possibility of selection bias.

Alternatively, it might be suggested that our population is too broad and should include only leading experts, such as those in the DSM-IV Work Group on dissociative disorders. However, the latter definition of consensus seems narrower than envisioned by DSM-IV, which states, “We took a number of precautions to ensure that the Work Group recommendations would reflect the breadth of available evidence and opinion and not just the views of the specific members . . . . members were instructed that they were to participate as consensus scholars” (p. xv).

In any event, our findings suggest that DSM-IV fails to reflect a consensus of board-certified American psychiatrists regarding the diagnostic status and scientific validity of dissociative amnesia and dissociative identity disorder. This finding is perhaps not surprising, given the existing evidence of controversy surrounding these disorders. This evidence includes the growing literature acknowledging this controversy

(1, 2, 7), the recent closure of several major dissociative disorders treatment units, the sharp shifts in the features of these disorders as described in successive editions of DSM, and published arguments that dissociative amnesia and dissociative identity disorder lack the degree of empirical support normally required for most other entities in DSM-IV

(8, 9).