Limitations of the Review

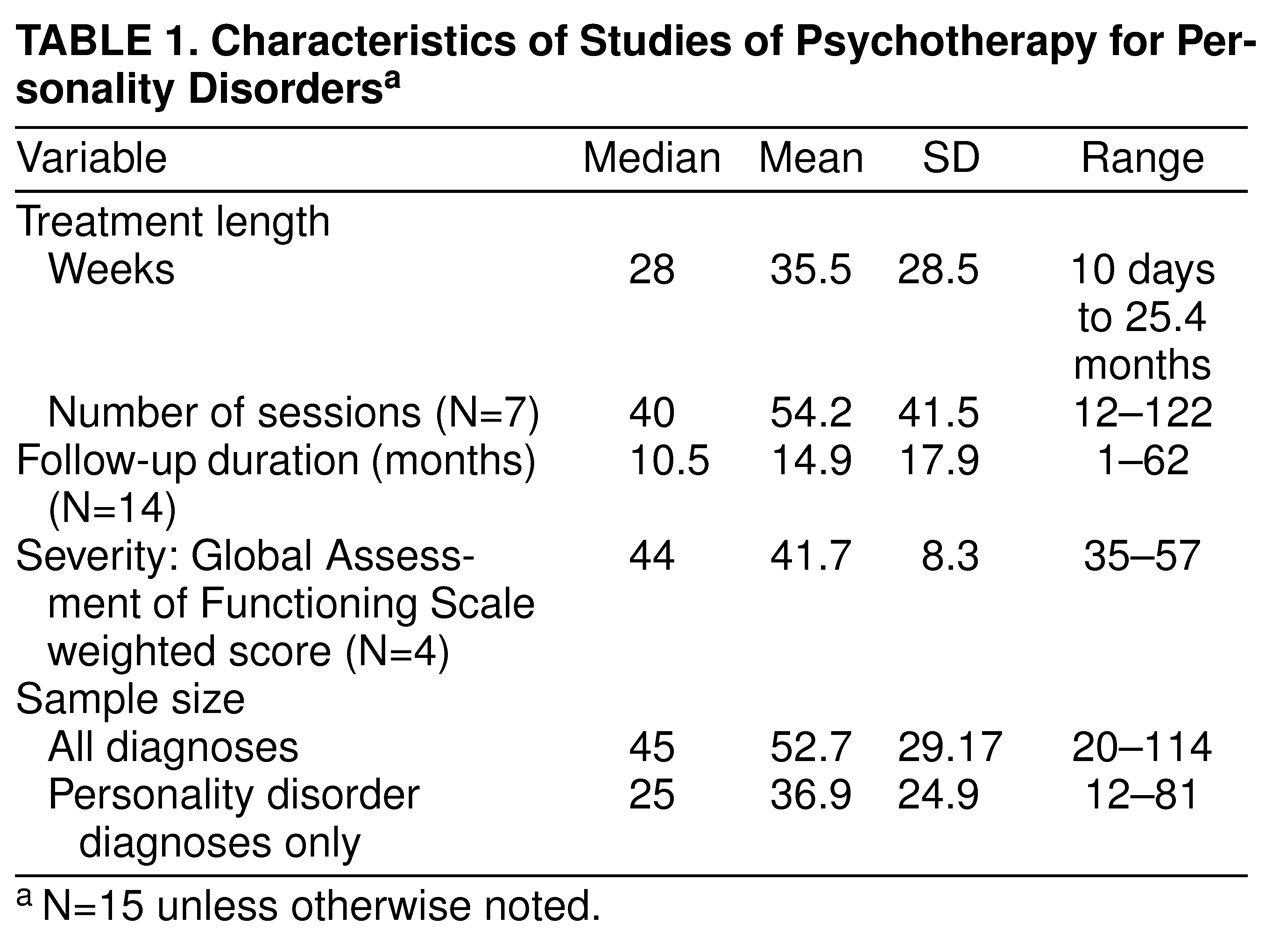

The major limitation of this review is the availability of only 15 studies from which our conclusions are derived. This is especially problematic given differences across studies in diagnoses, severity of illness, design, treatment modality and duration, and assessment methods. However, by using meta-analysis we were able to detect some consistent patterns. Nonetheless, further validation and detection of more specific effects will require substantially more studies. Meta-analysis itself has limitations

(25), such as equating studies within broad categories (e.g., dynamic or cognitive behavior therapy), which may obscure meaningful differences within treatment modalities

(26).

Another concern is generalizability to community populations seeking treatment. Patients not referred to a study, refusing to join, or dropping out before follow-up may differ in some significant way from patients admitted to and continuing in treatment. Any bias would limit generalization from these findings. This may be especially problematic when one is considering the results from a few studies, as we have done in comparing recovery from personality disorders. Few studies reported these data. In one exception, Stevenson and Meares

(11), reported that 48 (81%) of 59 eligible patients joined the study, 11 (23%) of the 48 dropped out, and a further seven (15%) were omitted from analyses because they decided to continue treatment beyond the 1-year study period. While intention-to-treat analyses would mitigate the effects of bias due to dropout, patients with personality disorders often drop out from follow-up assessments as well as treatment.

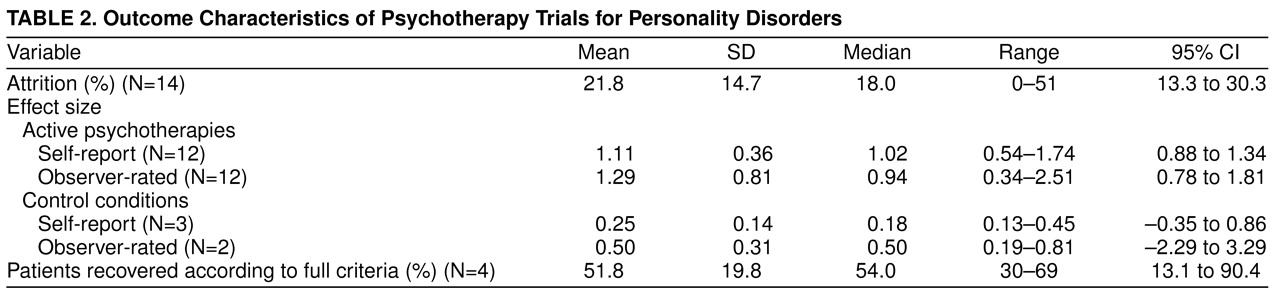

Treatment dropouts represent a special case of the potential for bias. The percentage of dropouts was significantly lower for treatments of shorter duration than for those of longer duration. After control for duration of treatment, the percentage of dropouts did not correlate with other study variables, decreasing the likelihood that dropout was a source of bias in our overall results. The overall mean rate of attrition (21%) compares favorably with that of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program

(27), which had a 31% dropout rate for personality disorders across all treatments, with the largest for clusters B (40%) and A (36%) and the lowest for cluster C (28%). The mean dropout rate of 28% for our longer-duration treatment studies is comparable to the mean dropout rate of 28% for the natural history follow-up studies

(1). This suggests that the present treatment studies were at no higher risk for bias due to dropout than these other studies of personality disorders. However, patient characteristics that predict dropout should be examined.

It is interesting that subjects with borderline personality disorder who agreed to participate in a randomized, controlled treatment trial comparing group therapy with individual therapy

(19) had a high dropout rate even before treatment began, after learning of their random treatment assignment (9% refused individual therapy and 19% group therapy, 28% total), as well as during the course of therapy (39% of those accepting assignment). In both cases the dropout rate was higher for group therapy. Budman et al.

(20) reported that 51% of patients dropped out of group therapy, especially those with borderline personality disorder. These investigators subsequently modified their treatment model to include individual sessions for patients with borderline personality disorder, similar to the model of Linehan et al.

(17). This suggests that acceptability to patients is a problem for group therapy in comparison with individual treatments. Further study is warranted, given the popularity of the group modality as a response to concerns about the cost of treatment. If limitation of treatment choice results in a high proportion of treatment refusal, especially for patients with borderline personality disorder, then clinical settings may ipso facto exclude patients needing treatment.

There was much heterogeneity in sample selection, including differences in personality disorder types, severity of illness, comorbidity, and treatment setting. Generally, cluster A disorders were least represented. Cluster B and C disorders were about equally represented, with cluster C disorders generally involving less impairment. However, the single type most often studied was borderline personality disorder. Thus, most of our conclusions are generalizable to a mix of personality disorder types with a high proportion of borderline patients.

The heterogeneity of diagnostic assessments across studies hampers comparison. This is worsened by the demonstrated lack of agreement between most diagnostic instruments when they have been compared

(4,

28,

29). However, whenever a high proportion of studies report similar findings despite such differences, it indicates a robust finding or signal, despite the noise. This is the case here.

The confounding of personality disorder types with treatment types and duration of treatment makes it difficult to conclude that any one type of treatment consistently demonstrates greater effects than no treatment or a comparison treatment. However, in the randomized, controlled treatment trials, all experimental treatments were superior to waiting-list or control treatment conditions.

The studies assessed outcome in a variety of ways, with no single measure used by most studies. While most studies included both self-report and observer-rated measurement perspectives, several used only one. Finally, in many instances it was not clear how clinically significant the results were, or whether the patients improved into a healthy range of scores.

Using pretreatment and posttreatment within-condition effect sizes permitted direct comparison of studies with different personality disorder diagnoses, study designs, outcome measures, and treatments, given that most lacked control/comparison groups. Lack of such a strategy makes meaningful summary even more difficult

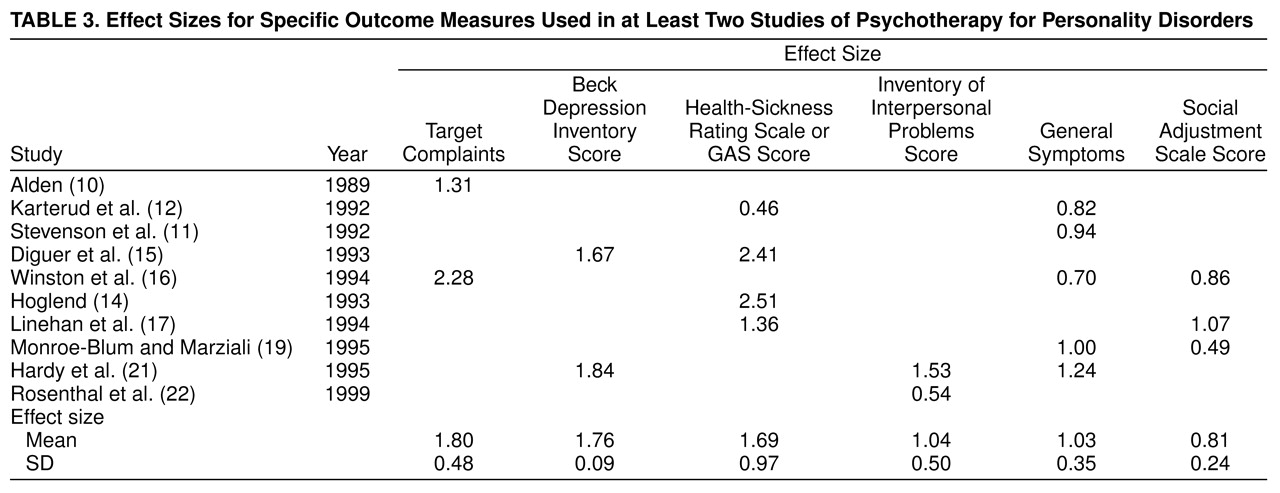

(30). One criticism is that the conclusions about effect size may lack specific meaning. However, the degree of improvement was sizable for all measures in

Table 3, so averaging them was also reasonable.

Within-condition effect sizes may overestimate true change, not adjusting for change due to attention alone, time, or regression toward the mean. However, using this approach for the three randomized, controlled treatment trials, we found larger effect sizes for active psychotherapy than for waiting-list or control treatments—differences of moderate to large magnitude, albeit significant only for self-report measures. Our analyses confirmed the original authors’ findings that each active treatment had significantly greater efficacy than the control conditions.

Recommendations

In the examination of these studies, several issues arose repeatedly, which should influence future studies.

1. More studies should examine the differential responses of specific types of personality disorder to specific psychotherapies, since existing data suggest that this is an important phenomenon.

2. In addition to demographic, diagnostic, and severity data, studies should report referral sources and rates of refusal to enter treatment as well as dropout rates. This will help in assessing the generalizability of the findings.

3. Randomized, controlled treatment trials will aid in comparing the effects of specific treatments across types of personality disorder or of treatments for the same type of personality disorder. The use of intent-to-treat analyses, which are used widely in pharmacological trials, should also aid in applying the interpretation of efficacy data to wider considerations of effectiveness.

4. By contrast, the field also needs more naturalistic, observational studies of patients in psychotherapy. As a source of “therapeutic diversity,” these will help us discover effective ingredients not presently in treatment manuals, thereby informing the next generation of treatments.

5. There should be efforts to standardize treatments and/or to describe and measure treatments actually delivered. Randomized, controlled treatment trials usually involve the use of a manual and training seminars followed by group supervision, as well as measurement of therapist competence and adherence to the manual

(38). Whenever studies use a naturalistic, observational approach or a treatment-as-usual comparison condition, investigators should assess what treatments were delivered. This may involve interviewing patients about the treatments or assessing taped sessions with the use of standardized measures.

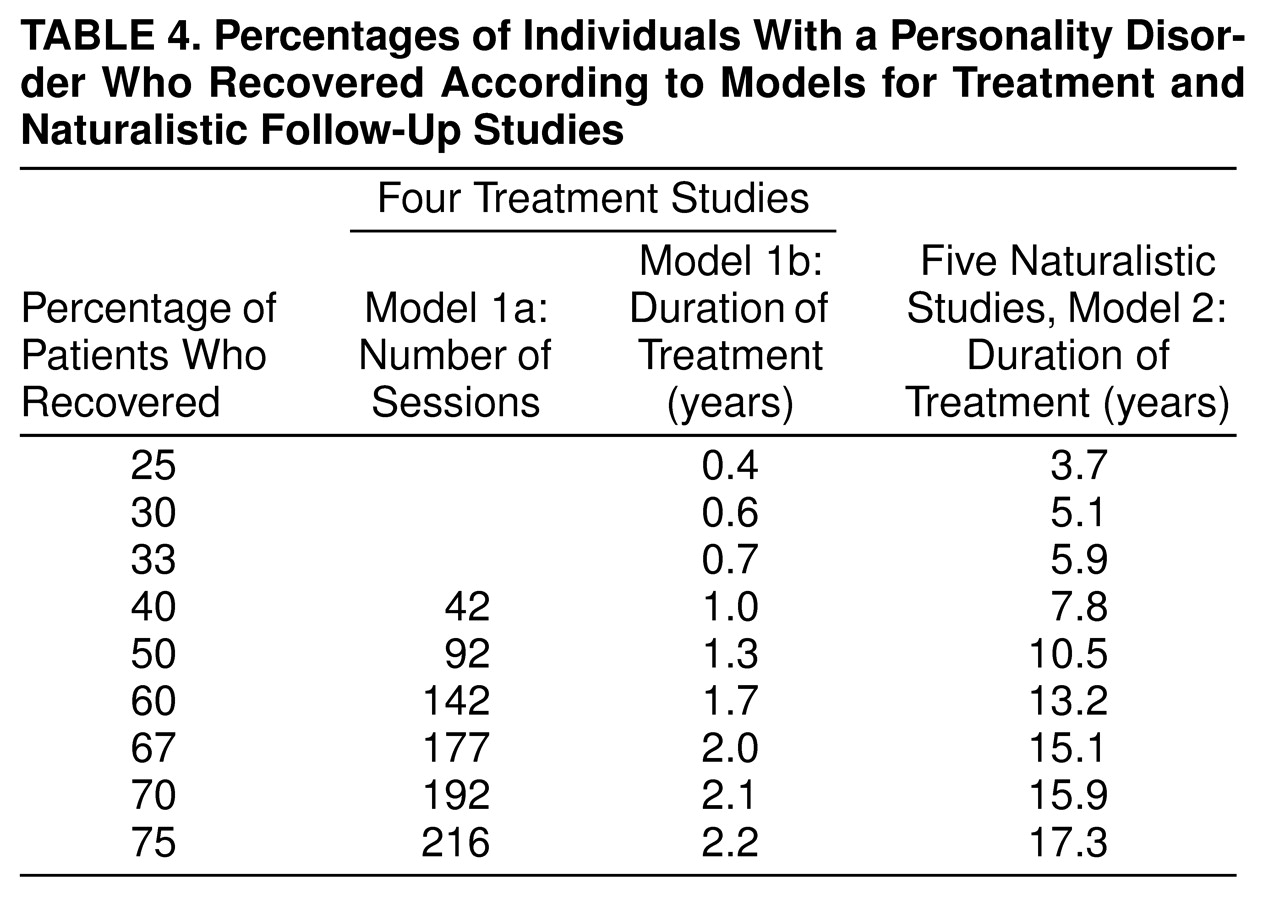

6. Studies should include longer durations of treatment. Most patients with personality disorders do not recover rapidly. Some who do recover rapidly may in fact represent false positive cases. Treatments of less than 1 year’s duration may better be characterized as treating crises, a series of crises, symptoms of distress, or a concurrent axis I disorder rather than core personality disorder psychopathology. Other researchers have drawn similar conclusions. Shea et al.

(27) found that at the end of 16 weeks of treatment, subjects with personality disorders had a lower recovery rate from major depression and were more impaired in social functioning than those without personality disorders, findings similar to those of Diguer et al.

(15). Kopta et al.

(37) demonstrated that characterologic change occurs much later than symptomatic change. Furthermore, characterologic change may actually continue after the end of treatment (delayed effects)

(14,

39). It would be useful, for instance, to determine the effective duration (i.e., “dose”) that produces recovery in 25%, 50%, and 75% of individuals with a given personality disorder type. Durations of treatment sufficient to obtain 50% recovery would facilitate detecting which characteristics of patients with personality disorders are highly responsive to treatment, which are responsive but likely to require longer treatment, and which are treatment-resistant and likely to require treatment modifications.

7. Greater uniformity of outcome measures across studies would improve comparison of findings. These should assess several domains of psychopathology and functioning, include observer-rated measures, not focus solely on distress-related symptoms, and include specific problem areas for each disorder. The data in

Table 3 suggest that measures vary in their effect sizes following treatment, and therefore reliance on more volatile measures (e.g., target complaints) may impede comparison with studies using measures that are more resistant to change (e.g., social functioning). Studies should also report the percentage of subjects no longer meeting the criteria for a personality disorder at follow-up, using similar measures at intake and follow-up to avoid errors due to poorly comparable methods

(4,

28).

8. Studies should include measures of core psychopathology purported to play a causal role in the development and/or maintenance of the disorders

(40). Improvement in putative core factors should predict remaining free of personality disorder traits. This should strengthen the links among diagnosis, mechanism of action, and response to treatment, adding to the convergent validation of both disorder and treatment. From a psychodynamic perspective, studies might include the assessment of defense mechanisms, the core conflictual relationship theme, or another dynamic formulation method

(41). From a cognitive behavior perspective, studies might assess dysfunctional attitudes, specific schemas, or response to a pathological schema-activation paradigm.

9. Finally, in the spirit of Wilhelm Reich’s early attempts to understand character

(42), studies should report data on patients who dropped out or deteriorated with treatment, to discover which treatments are not well tolerated or might adversely affect certain individuals. This involves a certain degree of scientific courage, however, which may require that the researchers be as well analyzed as their treatment findings!