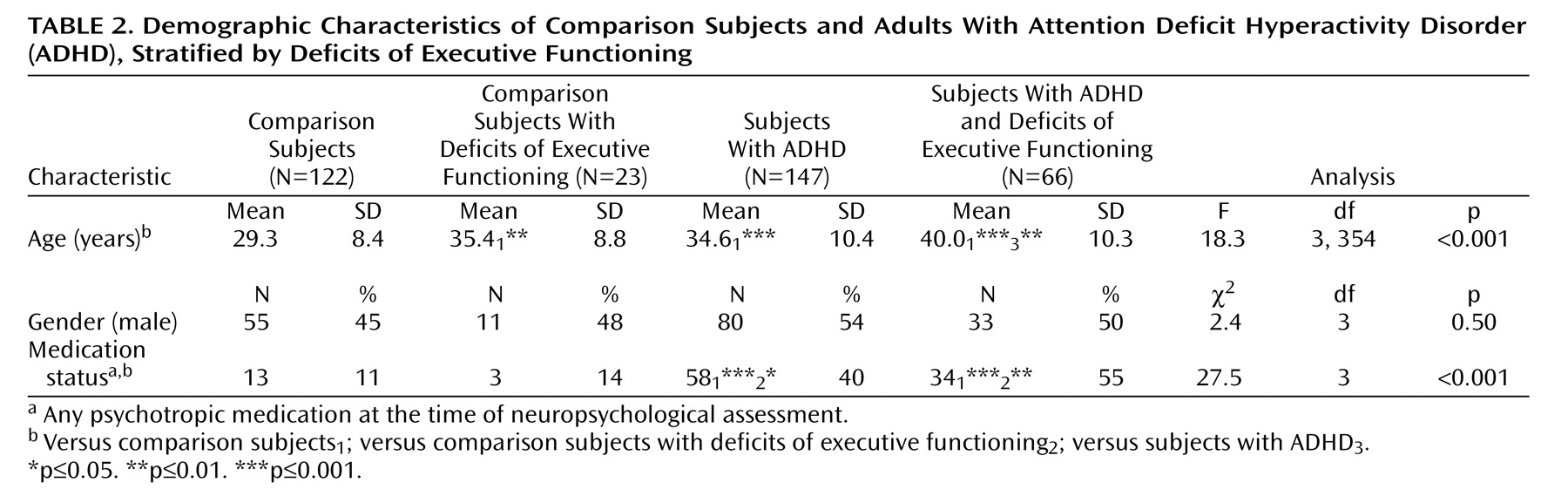

Subjects

Men and women between the ages of 18 and 55 were eligible for this study. We excluded potential subjects if they had major sensorimotor handicaps (e.g., deafness, blindness), psychosis, autism, inadequate command of the English language, or a full-scale IQ less than 80. No ethnic or racial group was excluded.

Subjects with ADHD were ascertained from referrals to a psychiatric clinic at a major university general hospital and media advertisements. We recruited comparison subjects without ADHD through advertisements and e-mail broadcasts to affiliated employees at the same institution.

A three-stage ascertainment procedure was used to select the participants. The first stage was the subject’s referral (for ADHD subjects) or response to media advertisements (for ADHD and comparison subjects). The second stage confirmed (for ADHD subjects) or ruled out (for comparison subjects) the diagnosis of ADHD by using a telephone questionnaire. The questionnaire asked about the symptoms of ADHD and questions regarding study inclusion and exclusion criteria. The third stage confirmed (for ADHD subjects) or ruled out (for comparison subjects) the diagnosis with face-to-face structured interviews with the individuals. Only subjects who received a positive (ADHD subjects) or a negative (comparison subjects) diagnosis at all three stages were accepted. After receiving a complete description of the study, the subjects provided written informed consent, and the institutional review board granted approval for this study.

Psychiatric Assessments

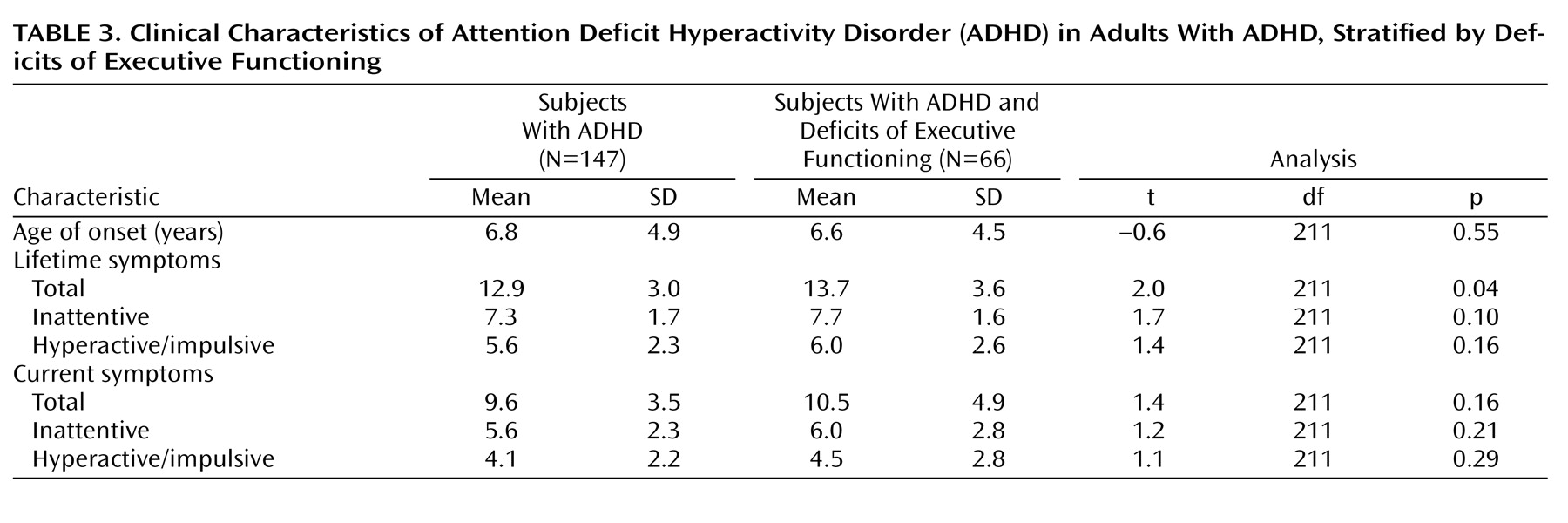

We interviewed all subjects with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)

(14) to assess psychopathology supplemented with modules from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Epidemiologic Version adapted for DSM-IV (K-SADS-E)

(15) to cover ADHD and other disruptive behavior disorders. The structured interview also included questions regarding academic tutoring, repeating grades, and placement in special academic classes.

The interviewers had undergraduate degrees in psychology, and they were trained to high levels of interrater reliability for the assessment of psychiatric diagnosis. We computed kappa coefficients of agreement by having experienced, board-certified child and adult psychiatrists and licensed clinical psychologists diagnose subjects from audiotaped interviews made by the assessment staff. Based on 500 assessments from interviews of children and adults, the median kappa coefficient was 0.98. Kappa coefficients for the diagnosis included the following: ADHD (0.88), conduct disorder (1.00), oppositional defiant disorder (0.90), antisocial personality disorder (0.80), major depression (1.00), mania (0.95), separation anxiety (1.00), agoraphobia (1.00), panic (0.95), obsessive-compulsive disorder (1.00), generalized anxiety disorder (0.95), specific phobia (0.95), posttraumatic stress disorder (1.00), social phobia (1.00), substance use disorder (1.00), and tics/Tourette’s syndrome (0.89). These measures indicated excellent reliability between ratings made by nonclinician raters and experienced clinicians.

A committee of board-certified child and adult psychiatrists and psychologists resolved all diagnostic uncertainties. The committee members were blind to the subjects’ ascertainment group, ascertainment source, and all nondiagnostic data (e.g., neuropsychological tests). Diagnoses were considered positive if, based on the interview results, DSM-IV criteria were unequivocally met to a clinically meaningful degree. We estimated the reliability of the diagnostic review process by computing kappa coefficients of agreement between clinician reviewers. For these clinical diagnoses, the median reliability between individual clinicians and the review committee-assigned diagnoses was 0.87. Kappa coefficients for individual diagnoses included the following: ADHD (1.00), conduct disorder (1.00), oppositional defiant disorder (0.90), antisocial personality disorder (1.00), major depression (1.00), mania (0.78), separation anxiety (0.89), agoraphobia (0.80), panic (0.77), obsessive-compulsive disorder (0.73), generalized anxiety disorder (0.90), specific phobia (0.85), posttraumatic stress disorder (0.80), social phobia (0.90), substance use disorder (1.00), and tic’s/Tourette’s syndrome (0.68).

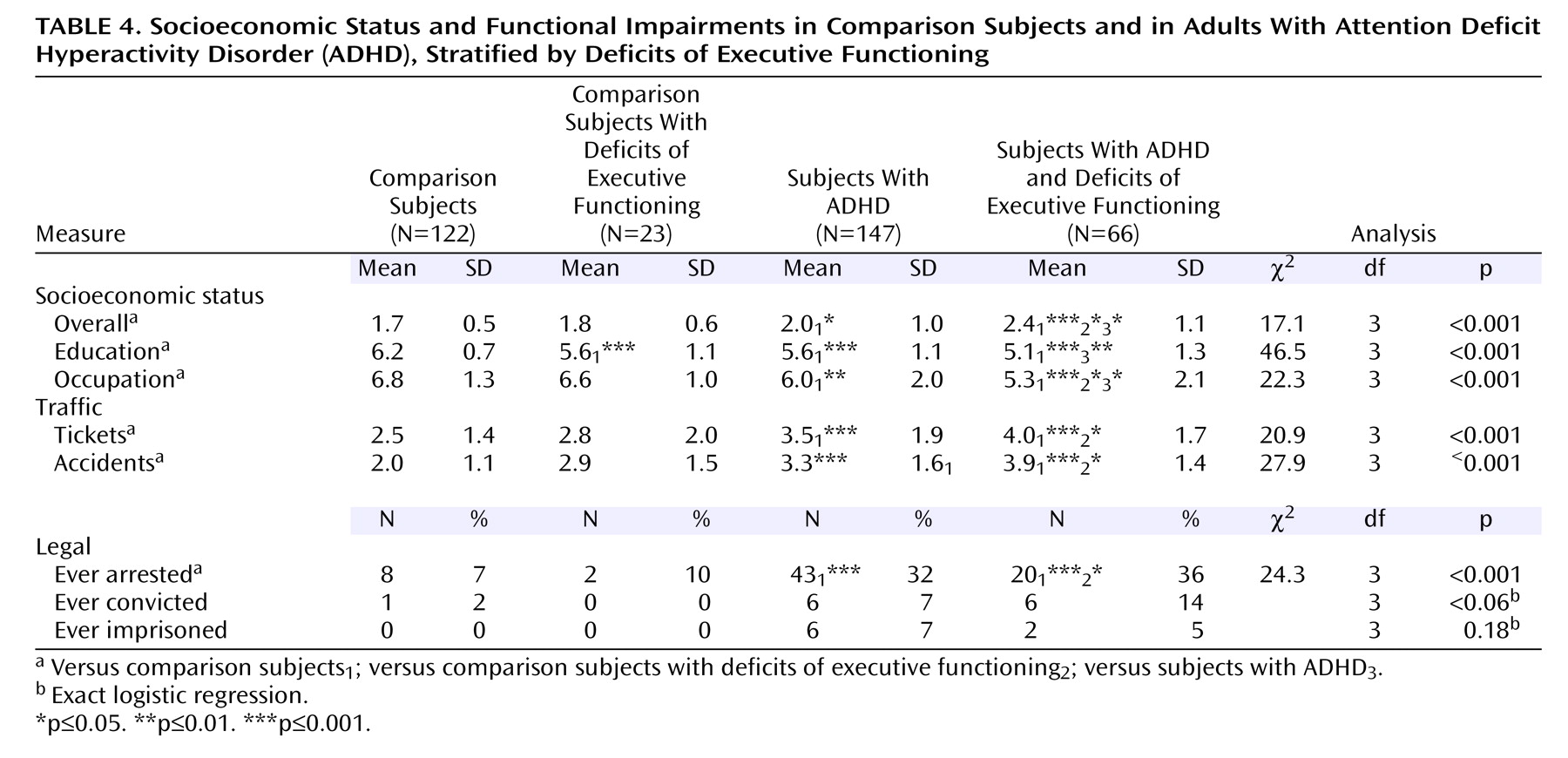

We created the following categories of disorders for this analysis: mood disorder (major depression with severe impairment and bipolar disorder), multiple anxiety disorder (two or more anxiety disorders), speech/language disorder (language disorder or stuttering), disruptive behavior disorders (childhood conduct and oppositional defiant disorder or adult antisocial personality disorder), and psychoactive substance use disorder (drug or alcohol abuse or dependence). Rates reported reflect a lifetime prevalence of disorders.

Cognitive/Neuropsychological Assessments

Using the methods of Sattler

(19), we estimated full-scale IQ from the vocabulary and block design subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scales—III (WAIS-III)

(20) . Our interviewers assessed academic achievement with the arithmetic and reading subtests of the Wide Range Achievement Test—III (WRAT-III)

(21) . As recommended by Reynolds

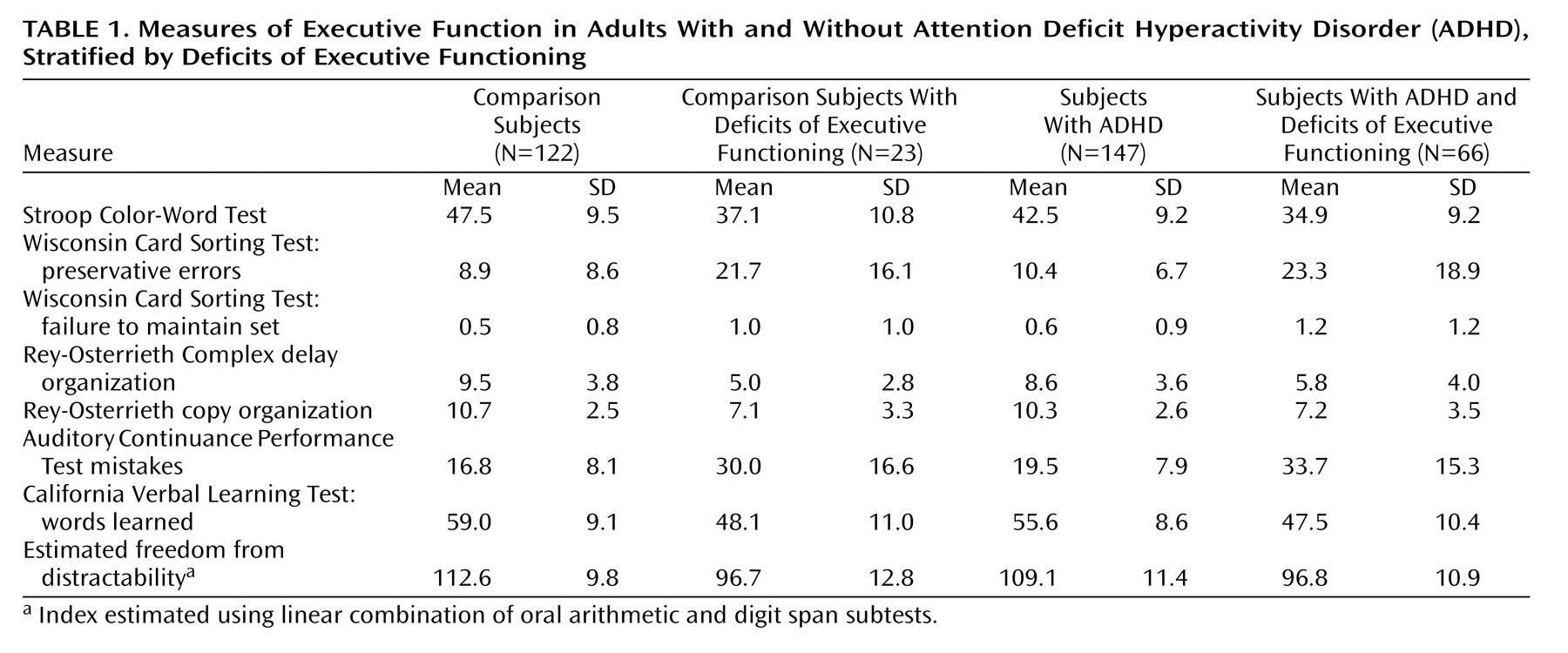

(22), we used a statistically corrected discrepancy between IQ and achievement to define learning disability. Based on our review of the literature and our previous neuropsychological work, we chose to assess certain domains of functioning thought to be important in ADHD and to be indirect indices of frontosubcortical brain systems. These included measures of sustained attention/vigilance, planning and organization, response inhibition, set shifting and categorization, selective attention and visual scanning, verbal and visual learning, and memory. The tests used were the following: 1) the copy organization and delay organization subtests of the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure

(23,

24), (scored with the Waber-Holmes method

[25] ); 2) an auditory continuous performance test developed to assess working memory

(26) ; 3) perseverative errors and loss of set of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

(27) ; 4) the total words learned on the California Verbal Learning Test

(28) ; 5) the color-word raw score of the Stroop test

(29) ; and 6) a score based on an additive combination of the WAIS-III digit span and oral arithmetic subtests

(20) to approximate the Freedom From Distractibility Index of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Third Edition (WISC-III)

(30) used in our previous analysis in a child and adolescent sample.