Clinical epidemiological studies provide a second line of evidence linking treatment with antipsychotic medications to an increased risk of hyperlipidemia

(11,

12) . In one case-control study, olanzapine and clozapine, but not risperidone or combination therapy, were associated with a significantly increased risk of hyperlipidemia

(11) . A second study reported no overall differences in the risk of hyperlipidemia between patients treated with clozapine or first-generation antipsychotic medications, although clozapine was associated with an increased risk of hyperlipidemia in the young adult cohort

(12) .

In relation to the accumulation of evidence linking clozapine and olanzapine to a worsening of the lipid profile, considerably less is known about the metabolic effects of the other second-generation antipsychotic medications. In the current study, we estimated the relative risk of hyperlipidemia after initial treatment with first-generation antipsychotic medications and each of the six currently available second-generation antipsychotic medications in relation to no antipsychotic medication treatment.

Method

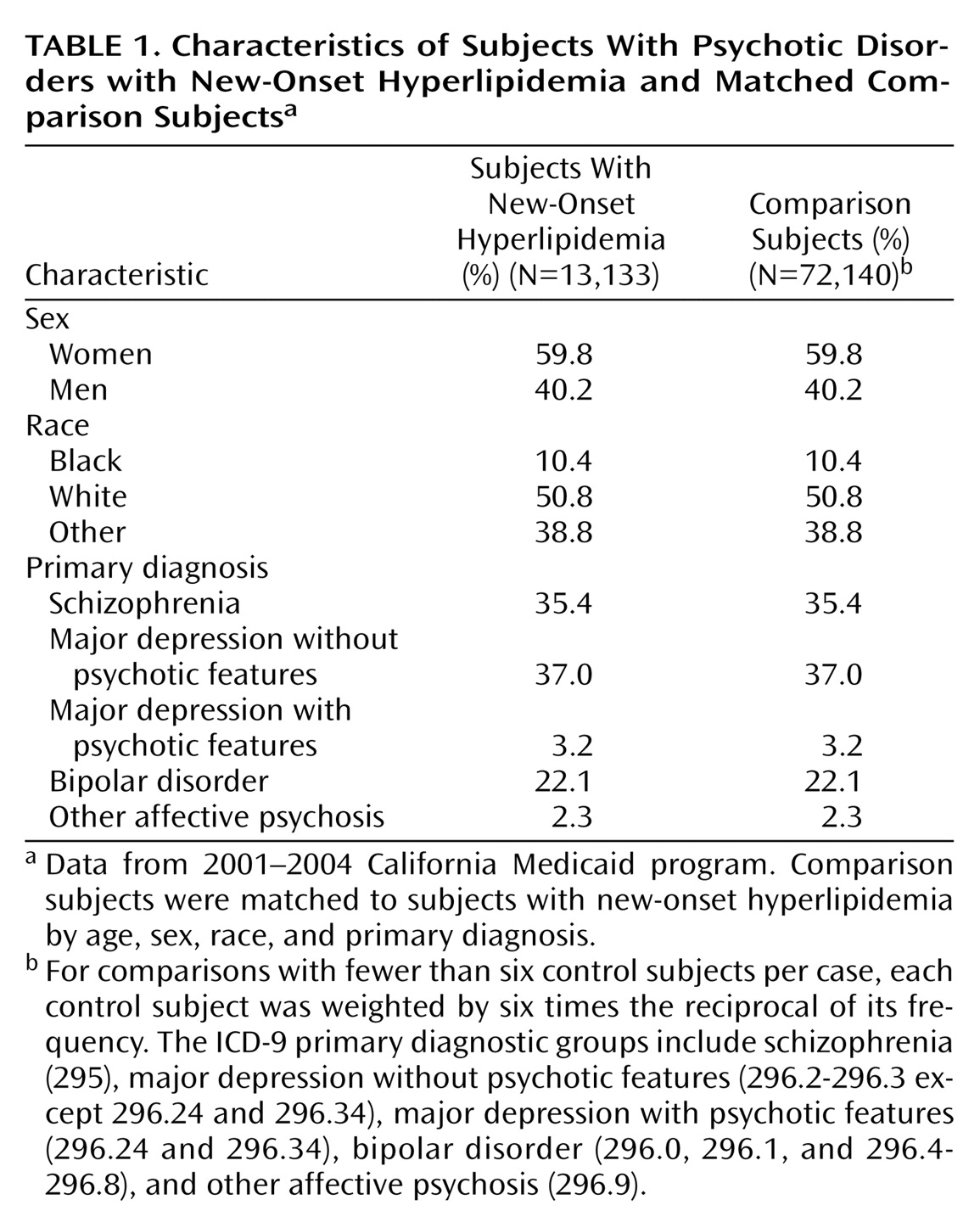

Data were culled from statewide claims of the California Medicaid program (2001–2004). The study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

The study cohort was first limited to patients ages 18 to 64 who received one or more claims for the treatment of schizophrenia (ICD-9:295) or an affective psychosis (ICD 296). Each patient was assigned on the basis of the number of claims to one of five diagnostic groups: 1) schizophrenia, 2) bipolar disorder, 3) major depressive disorder with psychotic features, 4) major depression without psychotic features, or 5) other affective psychosis.

Patients were excluded if they had medical conditions related to hyperlipidemia

(16) or filled prescriptions for medications related to hyperlipidemia

(17) before their index date, as defined. Medical conditions related to hyperlipidemia included hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, cholecystitis, acute intermittent porphyria, anorexia nervosa, type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, malnutrition, Gaucher’s disease, hepatitis, alcohol abuse/dependence, renal failure, sepsis, Cushing’s syndrome, pregnancy, acromegaly, lipodystrophy, multiple myeloma, autoimmune disorders, monoclonal gammopathy, and orchidectomy. Medications related to hyperlipidemia included thiazide and loop diuretics, retinoids, protease inhibitors, anabolic steroids, androgens, androgen-estrogen combinations, second-generation oral progestogens, growth hormone, immunosuppressive agents, amiodarone, enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants, nonselective beta-blockers, and oral corticosteroids.

Cases were selected for an incident diagnosis of hyperlipidemia (ICD-9 codes 272.0–272.4) or a prescription for atorvastatin, cholestyramine, clofibrate, colesevelam, colestipol, fenofibrate, fluvastatin, gemfibrozil, lovastatin, pravastatin, or simvastatin. Patients with a previous hyperlipidemia diagnosis or antilipemic prescription during the preceding 180 days were excluded from the analysis. The first date of hyperlipidemia diagnosis or dispensed antilipemic medication was defined as the index date. Subjects with hyperlipidemia (cases) and comparison subjects (controls) were limited to patients who, during the 60 days before their index dates, either filled no antipsychotic medication prescriptions or filled two or more prescriptions of only one type of antipsychotic medication.

For each case, up to 6 comparison subjects that did not have a diagnosis or treatment of hyperlipidemia were selected matched by age, sex, race, and diagnostic group. Each comparison subject was weighted by six times the reciprocal of its frequency. Comparison subjects were assigned the same index date as the case to which they were matched.

A total of 13,133 cases were selected from an initial pool of 55,662 potential cases. Potential cases were excluded if they were prescribed a medication or treated with a medical condition related to hyperlipidemia (N=18,774, 33.7%), filled prescriptions for more than one type of antipsychotic medication (N=6,955, 12.5%), filled only a single prescription for an antipsychotic medication during the 60-day period (N=8,959, 16.1%), were eligible for California Medicaid benefits for less than 180 days before their index date (N=24,453, 44.0%), or had been treated for hyperlipidemia during the 180-day period before their index date (N=26,844, 48.2%). These eligibility criteria were not mutually exclusive. The selected 13,133 incident cases of hyperlipidemia were matched to 72,140 comparison subjects.

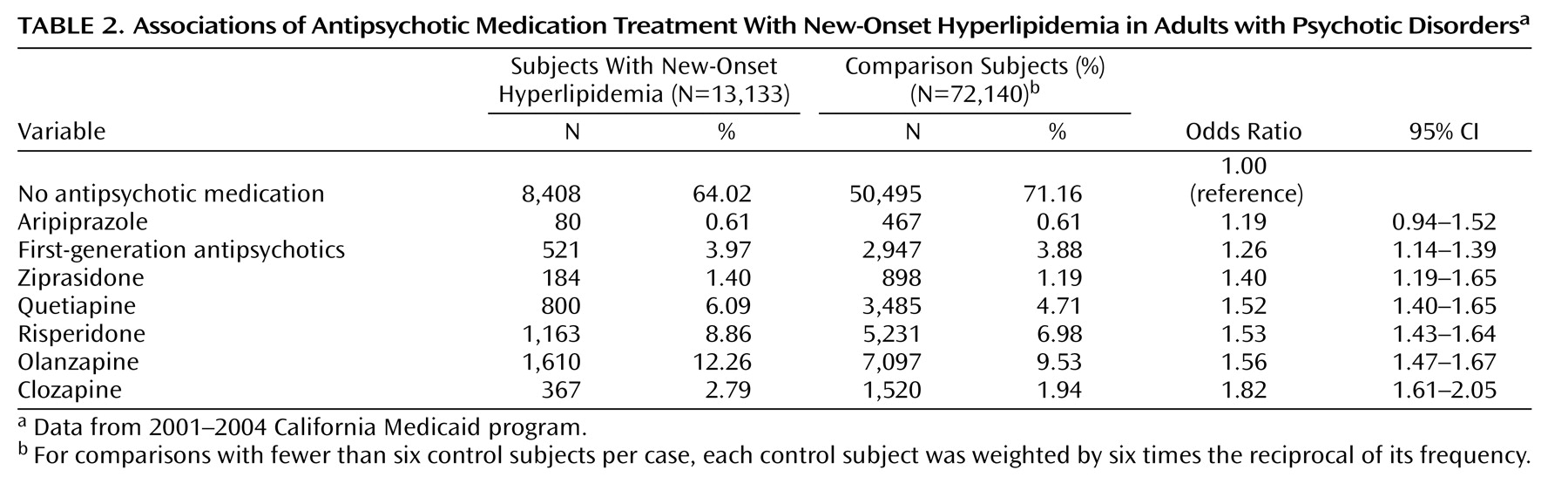

Antipsychotic medications were classified as aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, ripseridone, ziprasidone, or a first-generation antipsychotic medication. Antipsychotic treatment was defined as the dispensing of more than one prescription for an antipsychotic medication within 60 days of the index date.

A case-control analysis was performed. The effect of treatment with each antipsychotic medication during the 60 days preceding the index date on the odds of developing hyperlipidemia was modeled with conditional logistic regression. The reference group included all patients prescribed no antipsychotic medications during the 60 days preceding their index date. Results are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

Discussion

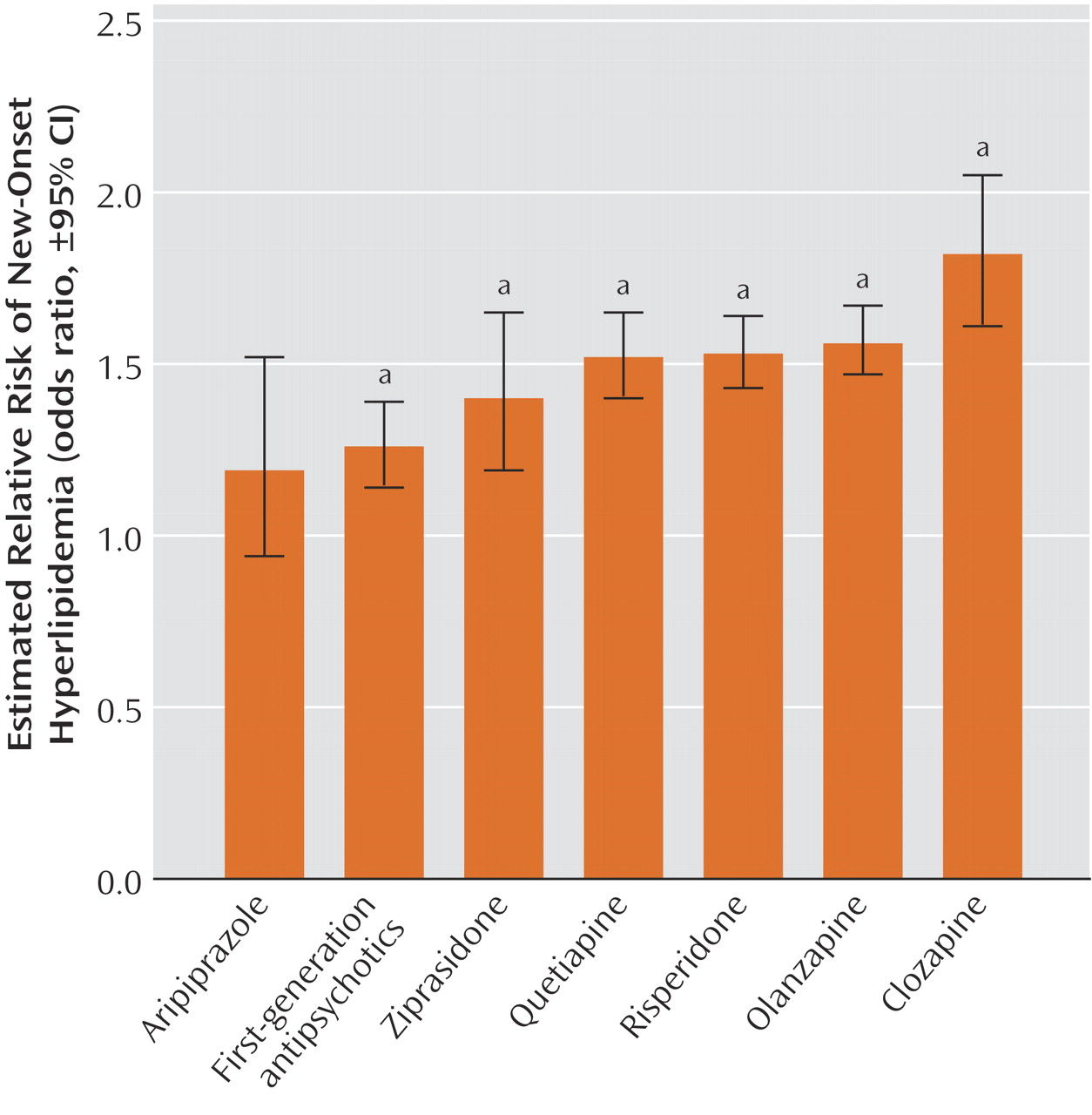

Across a range of antipsychotic medications, there was a significant association with increased risk of hyperlipidemia. First-generation antipsychotic medications and each of the second generation antipsychotic medications, except aripiprazole, posed a risk of hyperlipidemia that was significantly greater than the risk of no antipsychotic treatment. These findings extend earlier research concerning clozapine, olanzapine, and risperidone

(5,

6,

8,

11,

14) to include relevant information regarding quetiapine, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole.

The magnitude of the odds ratio of hyperlipidemia for olanzapine (odds ratio=1.56) was considerably smaller than previously reported from an analysis of the U.K. General Practice Research Database (odds ratio=4.52)

(11) . One possible explanation for this discrepancy concerns a variation in underlying practice patterns. Whereas only a small proportion of the subjects in the U.K. study (3%) were treated with second-generation antipsychotic medications, a much larger proportion of cases in the current study (32%) were prescribed second-generation antipsychotic medications. It is possible that in U.K. general practice, treatment with olanzapine and other second-generation antipsychotic medications are reserved for especially severely ill patients who may have higher rates of smoking

(18), obesity

(19), physical inactivity

(20), or other risk factors for hyperlipidemia that are common in severe mental illness but difficult to statistically control for in medical record based research. It is also possible that many U.S. physicians in the current study have become aware of the metabolic risks associated with olanzapine and are therefore relatively reluctant to prescribe it to their patients at high risk for developing metabolic abnormalities.

The current study has a number of limitations. First, antipsychotic treatment was measured with claims records rather than pill counts or electronic monitoring that might have yielded more accurate information. Second, no information was available concerning several well-known risk factors for hyperlipidemia, such as exercise level, diet, and body weight. Third, physicians may selectively prescribe antipsychotic medications partly on the basis of such risk factors and so attenuate observed associations between hyperlipidemia and some antipsychotic medications. Fourth, recorded diagnoses of hyperlipidemia and dispensed prescriptions of antilipemic medications probably underestimate the true incidence of hyperlipidemia in the study population

(21) . Fifth, because the study was limited to Medicaid beneficiaries, the results may not generalize to other populations that may differ in their awareness and recognition of hyperlipidemia

(22) . Sixth, because the study included relatively few subjects prescribed aripiprazole, the results concerning this antipsychotic medication should be interpreted with caution. Finally, the study included only nonelderly adults who may differ from children and older adults in their metabolic response to antipsychotic medications and in their underlying risk factor structure for hyperlipidemia

(23,

24) .

We provide evidence that several antipsychotic medications may contribute to the development of hyperlipidemia. Because patients treated for medical illnesses and prescribed medications known to be associated with hyperlipidemia were excluded from these analyses, the observed relationships between antipsychotic medication treatment and the risk of hyperlipidemia are independent of these known risk factors. Patients with schizophrenia and related mental disorders are approximately twice as likely as the general population to die of cardiovascular disease

(4) . In addition to an increase in lipid disorders, patients with severe mental disorders also have elevated rates of diabetes, obesity, hypertension, physical inactivity, and smoking, although several of these associations are less clearly established for severe mood disorders than for schizophrenia (see reference

5 ). In light of these risk factors, primary prevention of the metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease is an important aspect of care of severe mental disorders. Our results suggest that physicians should give careful consideration to potential cardiovascular and metabolic consequences before prescribing an antipsychotic medication.