The thalamus, a gateway for motor and sensory information to the cortex, is thought to play an important role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia

(1) . Several

(2 –

7) —but not all

(8,

9) —studies report smaller thalamic volumes in subjects with schizophrenia relative to healthy volunteers. Few studies attribute any single factor to the wide range of volume differences observed, although duration of illness

(8), gender

(10), and antipsychotic medication exposure

(11) are proposed. In the present study, we used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to measure thalamic volume in subjects with chronic schizophrenia who were treated with typical antipsychotic medications then switched to olanzapine. The hypothesis was that thalamic volume would be reduced after switching. The secondary hypothesis was that baseline thalamic volumes would be larger in subjects with chronic schizophrenia than in healthy volunteers and that volumes would not differ from volunteers after the switch to olanzapine.

Method

The subjects with chronic schizophrenia (N=10) were treated with typical antipsychotic medications continuously for at least 12 months before the baseline scan, switched to olanzapine, and rescanned approximately 1 year later. A comparison group of healthy volunteers was scanned in parallel.

The subjects were scanned with a Magnaton Vision 1.5-T MRI scanner (Siemens, Malvern, Pa.) by using a coronal inversion recovery sequence (4-mm slice thickness plus a 1-mm interslice gap). All images were assessed for motion artifacts. Measurements were made after a manual selection of regions of interest by using interactive shareware (NIH Image, version 1.62, developed at the National Institutes of Health and available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image)

(12) and a reference atlas

(13) . A single rater (B.K.) performed volumetric measures, blind to diagnosis, gender, and time of scan. Measurement of the thalamus began two slices posterior to the anterior commissure and included a total of four slices. Final area measurements were the mean of four independent trials. The white-to-gray pixel intensity of the inversion recovery sequence scans was 1.42, which was significantly better than the 0.89 white-to-gray pixel intensity of the three-dimensional volumetric spoiled gradient-recall acquisition data obtained from the same scanner. Total intracranial volume was ascertained (D.J.L. and V.M.G.) from T

2 -weighted axial images. Interrater reliability was high (N=10, intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] whole volume thalamus=0.96, ICC total intracranial volume=0.99).

Repeated-measures analysis of variance was performed, with time (baseline or follow up) and side (left or right) as within-subject factors, group (schizophrenia or healthy) as between-subject factors, and age as covariate. To compare thalamic volumes between groups at baseline and at follow-up, we performed repeated-measures analyses of variance with side (left or right) as a within-subject factor, group (schizophrenia or healthy) as a between-subject factor, and age as a covariate. Correlational analyses were performed to assess the relationship between thalamic volume and antipsychotic medication dosage.

Results

Detailed demographic data has appeared elsewhere

(14) . Briefly, healthy volunteers (N=20, 10 men, mean age=23.5, SD=7.7 years) were a subset (20 of 23) of those reported previously. The mean age of the subjects with schizophrenia (N=10, seven men, mean age=35.3, SD=8.8) was significantly greater than that of the volunteers (comparison subjects) (t=3.94, df=28, p=0.0005), and the interscan interval (schizophrenia: mean=56.0 weeks, SD=17.1, volunteers: 60.1 week, SD=12.7) was shorter (t=2.13, df=28, p=0.04). Initial analyses with all subjects used age as a covariate. Secondary analyses used the older 10 of the 20 volunteers. For this subsample (six men and four women), mean age did not differ between groups (t=1.79, df=18, p=0.09) nor did intracranial volume (t=0.22, df=18, p=0.83).

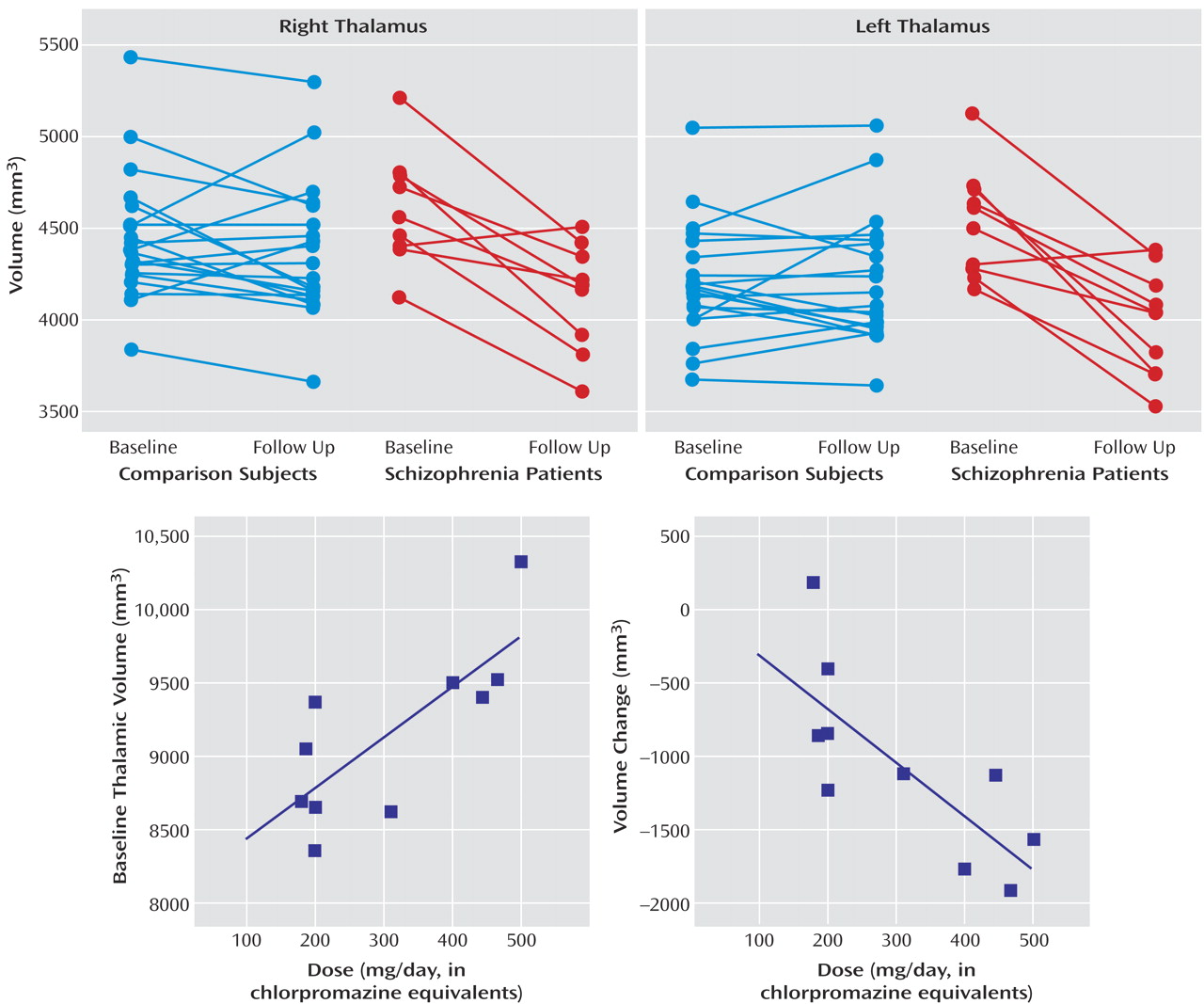

No main effects of diagnosis (Wilks’s λ=1.85, df=2, 26, p=0.18) or time (Wilks’s λ=0.67, df=2, 26, p=0.52) were observed. A time-by-diagnosis interaction (Wilks’s λ=9.75, df=2, 26, p=0.001) was noted. This interaction was also present in the age-matched subgroup (Wilks’s λ=8.80, df=2, 16, p=0.003). On both the left and right sides, thalamic volume was reduced after the switch to olanzapine (

Figure 1 ).

Mean baseline total thalamic volume was 5.8% larger in schizophrenia patients than in volunteers (F=4.96, df=1, 27, p=0.03). A similar difference was present in the age-matched subgroup (F=6.88, df=1, 17, p=0.02). Conversely, at the follow-up scan, no difference related to diagnostic group was detected in the total group (F=0.54, df=1, 27, p=0.47) or in the subgroup (F=0.52, df=1, 17, p=0.48). One subject was briefly treated with an antidepressant near the time of the baseline scan, and one subject was similarly treated near the time of the follow-up scan. Neither subject had results that were different from the pattern of the others.

A positive correlation between baseline thalamic volume and chlorpromazine-equivalent dosage of medication was observed (r=0.77, p=0.009) (

Figure 1 ). A significant correlation between change in thalamic volume (follow-up minus baseline) and baseline dosage of typical antipsychotic medication was also observed (r=0.76, p=0.01). A higher baseline dose was associated with a greater reduction of total thalamic volume between baseline and follow-up scans (

Figure 1 ).

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that switching patients from typical antipsychotic medications to olanzapine resulted in reductions in thalamic volume. These changes represented normalization of previously larger volumes, which were associated with the dosage of typical antipsychotic medication administered.

A previous study reported a tendency toward larger thalamic volumes in patients with schizophrenia who were treated with typical antipsychotic medications and a strong positive correlation between dosage and baseline thalamic volume

(11) . This correlation was much stronger than correlations between the dose of typical antipsychotic medication and the volumes of basal ganglia structures. The present study is the first to report a reduction in thalamic volume after switching from typical to atypical antipsychotic medications. The results suggest that the hypertrophic effects of typical antipsychotic medications extend beyond the basal ganglia.

There are several limitations to the present study. The findings may have been influenced by MRI acquisition protocol, slice thickness, the presence of interslice gaps, and the white-to-gray tissue contrast. Slice thickness and the presence of interslice gaps, in particular, prevented us from segmenting the thalamus into its major nuclei. However, our thalamic volumes fell well within the range of those reported in the postmortem and MRI literature

(9) . In addition, there was high interrater reliability for thalamic volume.

In summary, treatment with typical antipsychotic medications was associated with enlargement of the thalamus in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Switching to olanzapine reduced thalamic volume to a size slightly smaller than that of healthy volunteers. Antipsychotic medications could contribute to the wide range of thalamic volumes reported in schizophrenia.