In the last decade of the 20th century, clinical investigators were finding high rates of recurrence in the newer studies of pharmacotherapy alone

(1) and began to explore the potential benefits of adding a psychoeducational or psychotherapeutic intervention to pharmacotherapy in the prevention of bipolar recurrence. The assumption was that, if nothing else, psychotherapy might improve the generally poor adherence to pharmacotherapy observed in this patient population. The hope was, however, that a psychotherapeutic approach might have benefits, including enhancing social and occupational functioning, enhancing capacity to manage stressors in the social/occupational milieu, enhancing the protective effects of family and other social supports, decreasing denial and disorder-associated trauma, and encouraging acceptance of the disorder.

Data from controlled clinical trials now exist supporting individual psychoeducation

(16), group psychoeducation

(17), several variants of cognitive therapy

(18 –

20), family-focused treatment

(21,

22), and an adaptation of interpersonal psychotherapy

(15,

23) as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy in the prevention of recurrence. The psychoeducational approaches tend to emphasize education about the disorder itself and about the treatments used to manage it along with a strong focus on the recognition of early warning signs of impending episodes and the development of an action plan when these early warning signs are present. The cognitive approaches have tended to adhere fairly closely to Beck et al.’s model

(24) in the treatment and prevention of depressive episodes, with additional components to address the cognitive distortions associated with mania and hypomania and negative cognitions related to “dependence” on medication. The family-focused approach of Miklowitz and Goldstein

(25) grew out of data indicating the negative impact of a family environment characterized by criticism and emotional overinvolvement in provoking bipolar recurrences. The treatment, therefore, emphasizes education of all family members regarding the disorder and training in positive and productive communication.

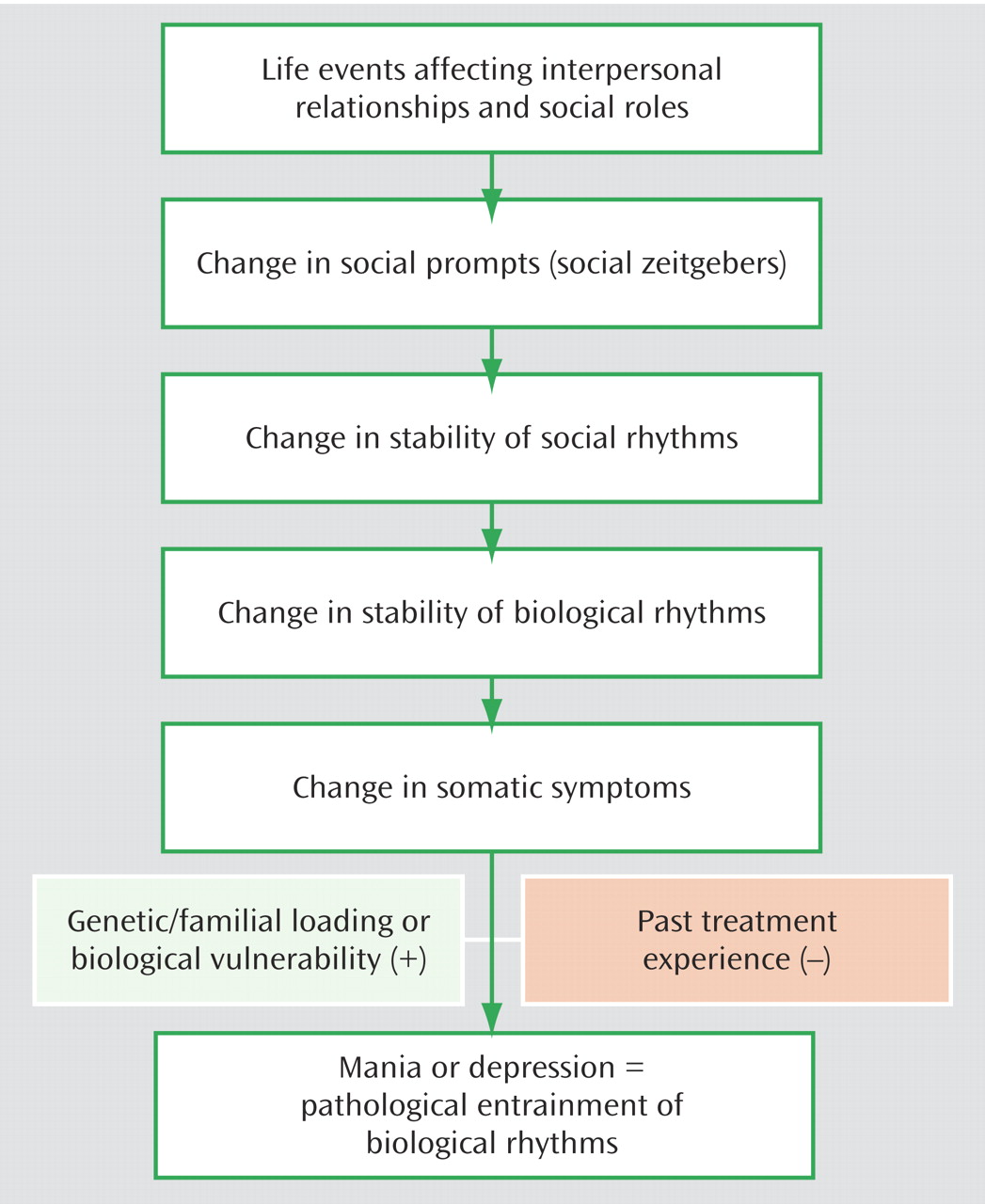

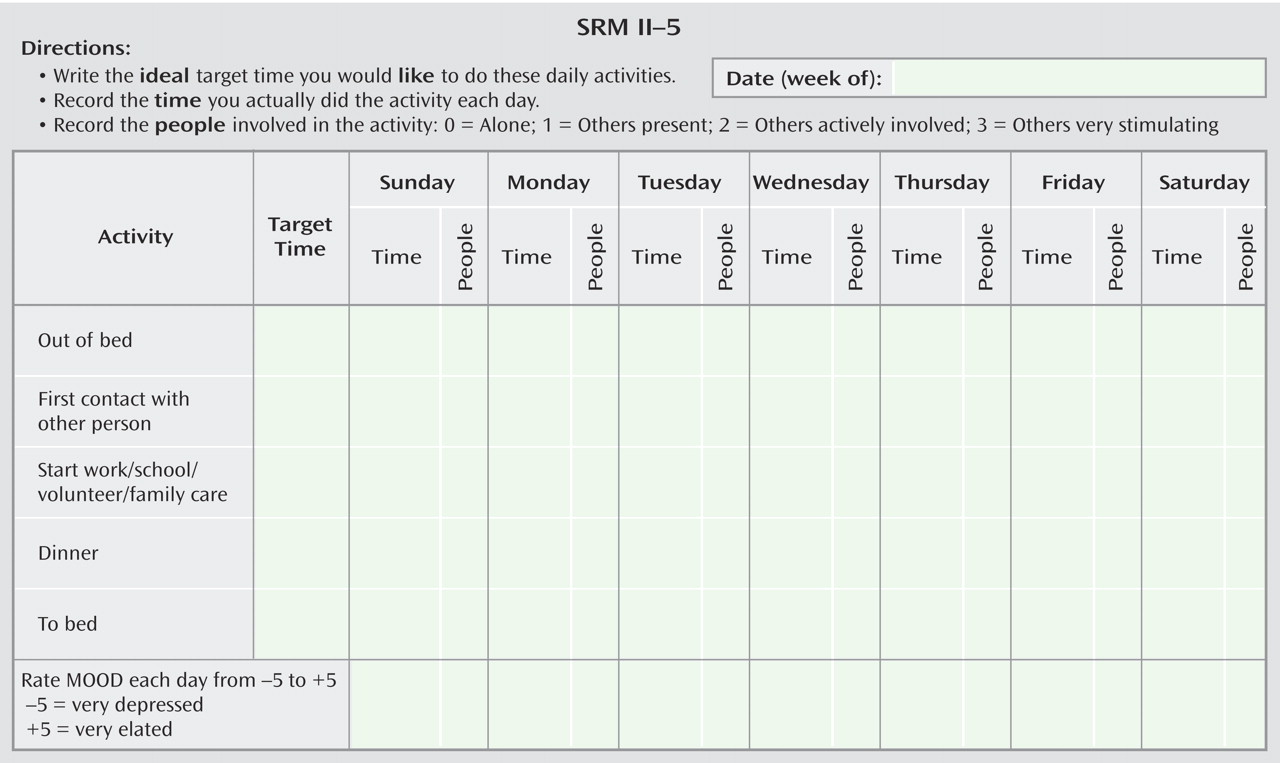

Our own research group, with its strong interest in the relationship of the circadian system to mood disorders, developed an intervention aimed at prevention of recurrence that we called interpersonal and social rhythm therapy

(23) . Our idea was that a behavioral approach aimed at increasing the regularity of patients’ daily routines, and especially their sleep/wake cycles, could shore up what we viewed as their vulnerable circadian systems. In the behavioral component of this intervention we first assess, using a self-report charting device called the Social Rhythm Metric, the extent to which a patient’s routines vary in their timing from day to day (see

Figure 2 ). We put particular emphasis on the timing of going to bed, rising, work, meals, and social contact. Then, again using the Social Rhythm Metric as a guide, we work with the patient to help him or her to make those routines more regular in their timing. Using behavioral strategies such as chain analysis and successive approximation, we seek to have the timing of those key activities vary by no more than an hour. We also search the “landscape” of the patient’s life for potential triggers to rhythm disruption, such as having house guests or taking a vacation. We then problem-solve with the patient about how to maintain the maximum regularity of routine possible in the face of such disruptions. By weaving this approach together with work on the four problem areas (grief, role transitions, role disputes, and interpersonal deficits) specified in interpersonal psychotherapy as developed for unipolar disorder by Klerman and colleagues

(26), we hoped to protect the vulnerable circadian systems of individuals with bipolar disorder, improve their acceptance of the illness, decrease interpersonal and social role distress, and improve social role functioning. In a controlled trial of 175 patients with bipolar I disorder, we have now shown that acute treatment with interpersonal and social rhythm therapy is associated with significantly reduced risk of recurrence of both depression and mania over a subsequent 2-year period

(23) . Furthermore, we found that the protective effect of the treatment was directly related to the extent to which patients increased the regularity of their social rhythms.