According to DSM-IV-TR, a hallucination is “a sensory perception that has a compelling sense of reality of a true perception, but occurs without external stimulation of the relevant sensory organ.” Thus, an auditory hallucination is a false perception of sound. These are the most common forms of hallucinations

(1) . Auditory hallucinations are found most often in patients with schizophrenia, with a prevalence of 75% in that population

(2) . However, auditory hallucinations have been described in conjunction with many life circumstances and diseases, including religious phenomena, bereavement, drug intoxication, sensory deprivation, and near-death experiences, as well as psychiatric or neurological disorders. Auditory hallucinations have been estimated to occur in 10%–15% of those without neuropsychiatric illness

(3) . Auditory hallucinations have been linked to left-brain alterations in imaging studies, more specifically Broca’s area, the anterior cingulate, the superior temporal lobe, and the primary auditory cortex

(4) . Many historical figures, from Socrates and Caesar to Descartes and Joan of Arc, have been reported to “hear voices”

(5) . Although the meaning, significance, and etiology of these voices depend on their context, auditory hallucinations are most often a symptom of severe, disabling psychiatric or neurological illness. This article recounts the treatment course of a patient with new-onset auditory hallucinations. To highlight the importance of taking a thorough history, we present the relevant data longitudinally, in the same manner in which it was obtained.

Discussion

New-onset paranoia and hallucinations in a 52-year-old man have a broad differential diagnosis. Intoxication or withdrawal from substances of abuse can cause psychosis at any age. Metabolic disorders, such as hypercalcemia, hyponatremia, uremia, hepatic encephalopathy, thyroid disorders, hypoglycemia, vitamin deficiencies, and porphyria, can cause delirium associated with hallucinations and delusions. Autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and temporal arteritis, can also cause psychosis, as may any CNS vasculitis. Drug toxicity is another common cause of delirium. Extrapyramidal disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease, can cause psychotic symptoms. Hallucinations can be the presenting symptom of CNS infections, such as acute viral encephalitis, HIV or AIDS, encephalopathy, syphilis, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurological conditions, such as demyelinating diseases, dementia, stroke, seizures, and CNS neoplasms, may also present with psychotic symptoms

(6) . Therapeutic doses of bupropion in the elderly have been linked to psychotic reactions, but in most of these case reports, there were additional factors that may have contributed, such as co-prescription of other psychotropic medications or a prior history of psychosis

(7) .

Alzheimer’s disease has been associated with up to a 60% incidence of psychotic symptoms at some point in the disease course

(8) . The prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease increases with age; its prevalence is less than 1% in the population below 65 years of age

(9) . There are, however, early-onset variants associated with specific genetic mutations in which patients may develop dementia in their 30s

(9) . Hallucinations in Alzheimer’s disease are more likely to be visual than auditory.

Another dementia, Pick’s disease, is more likely to appear at an earlier age, with personality changes, but psychotic symptoms are rare

(8) . Lewy body disease is more likely to present with psychosis, especially visual hallucinations

(8) . In a population-based study of patients with Parkinson’s disease, 16% reported hallucinations or delusions, although rates as high as 40% were seen in nursing home patients

(10) . In Parkinson’s disease, psychotic symptoms are usually precipitated by drug treatment and occur years after the onset of the illness

(8) . Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease frequently appears as an organic psychosis

(8) . In vascular dementia, psychotic symptoms are similar to those of patients with Alzheimer’s disease

(11) .

Psychiatric considerations are primarily mood disorders and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is most likely to appear in a patient’s third decade, with an incidence of less than 0.1% in men in their 50s

(12) . Late-onset schizophrenia, defined as onset after 40 years of age, has a 1-year prevalence rate of 0.6% and is more common in women

(13) . Mr. A’s birth month, August, is associated with a low relative risk for the future development of schizophrenia

(14) .

The median age of onset for mood disorders is 30 years

(15) . Psychotic depression has been suggested as a precursor of bipolar disorder

(16) . Bipolar disorder usually appears in the second or third decade of life, but 10% of patients have their first episode after the age of 50

(15) . When it appears after age 50, psychotic depression often presents with severe agitation, delusional guilt, hypochondriasis, early-morning awakening, and weight loss

(17) .

Discussion

A close association between epilepsy and psychosis has been noted from the beginnings of neurology and psychiatry as disciplines

(8) . Psychotic symptoms have been noted to appear during ictal events, postictally, between ictal events, and after lobectomy for seizures in treatment-resistant epilepsy. The emergence of psychotic symptoms after seizures are well controlled is the basis of the concept of “forced normalization.” Seizures were also used to treat schizophrenia in the form of ECT. Psychiatric symptoms are often the major or sole presenting sign in epileptic patients. For example, 25% of auras are characterized by psychiatric symptoms, such as panic or depression

(21) . At times, patients and their families may not notice motor symptoms or alterations in consciousness, and these seizures may be mistaken for panic attacks. Hallucinations can also be a prominent component of seizures, more common when the seizure focus is in the left temporal lobe

(22) . A diagnosis of epilepsy might not be considered until the patient’s seizures progress to secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

The term “schizophrenia-like psychosis of epilepsy” was proposed by Slater et al. in 1963 because they demonstrated that all of the symptoms of classic schizophrenia are seen in patients with psychosis and epilepsy

(23) . They noted that the marked social withdrawal seen in schizophrenia is not common in patients with “epileptic psychosis.” The average age of these patients was 30 years, and the mean duration of their epilepsy was 14 years. Subsequent studies have shown that patients with epilepsy and psychosis show less premorbid personality pathology, better social and occupational functioning, and a more favorable prognosis than patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia-like psychosis of epilepsy has been noted in 3%–7% of patients with epilepsy

(24) .

Cognitive testing has shown that patients with schizophrenia-like psychosis of epilepsy show lower scores on tests of attention, memory, and executive functioning in relation to normal comparison subjects. The group with schizophrenia-like psychosis of epilepsy, however, did not show deficits as extensive as the patients with schizophrenia

(24) . The development of psychotic symptoms follows the onset of seizures by approximately 14–17 years

(25) . In contrast to the significant genetic contribution in the development of schizophrenia, studies have suggested a lack of heritability of schizophrenia-like psychosis of epilepsy. However, a well-powered study has yet to be performed on the genetics of patients with psychosis of epilepsy

(26) .

Psychosis in patients with epilepsy usually responds to a combination of anticonvulsants and antipsychotics. To our knowledge, there is one case report of intravenous lorazepam used successfully in a treatment-resistant patient

(27) . Two main syndromes of epilepsy-associated psychosis have been studied: postictal and interictal psychosis

(21) . Postictal psychosis is associated with an increase in the frequency of generalized tonic-clonic seizures (clustering) before the onset of psychosis. There is usually a lucid interval of 12–120 hours between the last seizure and the psychotic symptoms. The psychosis can persist for several hours or up to weeks. Mood and anxiety symptoms can be prominent. Insomnia is usually a warning sign of impending psychotic symptoms, and patients usually respond to antipsychotic medication. Interictal psychosis, on the other hand, can occur at any time between seizures but is considered to be less episodic. The patient usually has a clear sensorium

(21) . Pathophysiological differences between epilepsy patients with and without psychosis have been reported. Psychosis is seen more often in patients with a left temporal lobe focus, but in postoperative psychosis, it occurs predominantly in patients who have had right temporal lobe surgery

(26) .

Patients with psychosis and epilepsy have been shown to have greater ventricular enlargement, more periventricular gliosis, and more focal brain damage than patients with epilepsy without psychosis

(25) . Significant bilateral amygdala enlargement, along with smaller brain volumes, has been seen in patients with epilepsy and psychosis in relation to patients with epilepsy only and normal comparison subjects

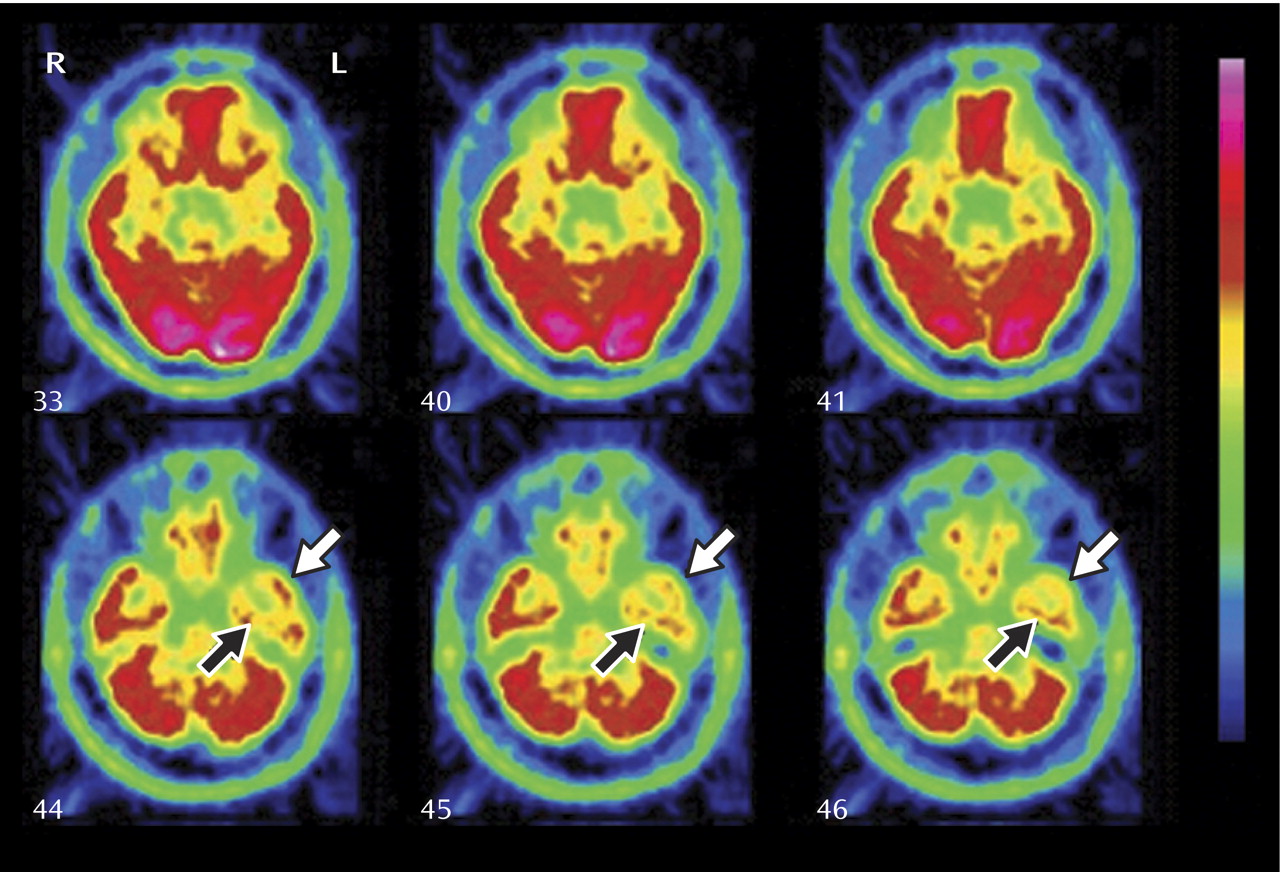

(28) . In PET studies, epileptics with psychosis showed decreased metabolism in the frontal and temporal regions and in the basal ganglia

(29) . Single photon emission computed tomography studies have also shown decreased blood flow in the left medial temporal region in psychotic patients with epilepsy

(30) . Pathological data from temporal lobectomies have shown that patients with schizophrenia-like psychosis of epilepsy have shown larger lesions and lesions more often associated with fetal or perinatal misdevelopment. Gangliogliomas (developmental lesions containing aberrant neurons) were more often associated with the development of psychosis

(22) . Because psychosis tends to develop years after the onset of epilepsy, it has been postulated that a kindling effect occurs

(31) .

Bupropion has been associated with an increased risk of seizures, but this is limited to the immediate-release form of the drug. Rates of seizure occurrence with the slow and extended release of the drug are actually similar to those of other antidepressants

(7) . The incidence of seizures with sustained-release bupropion was 0.1% in a 1-year follow-up study of more than 3,000 patients in an open-label study

(32) . In the Wellbutrin XL (extended-release bupropion) package insert, the incidence of seizures is cited as 0.1% in patients taking up to 300 mg/day of sustained-release bupropion and 0.4% in patients taking between 300 mg/day and 450 mg/day of immediate-release bupropion

(33) . Patients taking doses above 450 mg/day have an incidence of seizures of over 2%

(34) .

Antipsychotic medications are known to lower the seizure threshold, but the incidence of seizures with newer-generation antipsychotics, such as risperidone and olanzapine, does not differ from placebo

(35) . Quetiapine may be the least likely of the class to induce seizures; EEG abnormalities are rare after quetiapine treatment, at a significantly lower rate than with olanzapine treatment

(36) . Epilepsy usually appears in children and adolescents and in the elderly. The incidence of seizure onset at age 50 is less than 1%

(37) . The incidence is highest in children (up to 3.5%) and in those over age 80 (over 4%). In most seizure patients, a cause is not found. Most common etiologies that are discovered are the following: stroke (11%–21%), congenital origin (5%–7%), neoplasm origin (4%–7%), trauma (0%–6%), and degenerative disorder (2%–5%) (38). In patients with late-onset seizures (starting after the age of 20), one study found that the causes are more often related to chronic alcoholism (24.8%), brain tumors (16.4%), stroke (13.2%), and trauma (11.2%)

(39) . Another study found that 4% of all patients with solid tumors had seizures

(40) . Seizures can be the initial sign of a CNS tumor and can occur years before diagnosis. Computerized tomography (CT) scans often do not detect small tumors, especially in the temporal region, and MRI may only show minimal changes. Patients with temporal lobe tumors have variable EEG findings between seizures. In one case series of 52 patients, focal spikes were seen in 25% of interictal EEGs, sharp waves in 23.1%, and persistent temporal focal slowing without spikes in 13.5%

(41) . Seven of 45 of another series of patients with space-occupying lesions and epilepsy showed no EEG abnormalities

(39) . There are multiple pathogenic mechanisms by which tumors may cause seizures, including pH changes, cerebral edemas, changes in neuronal and glial enzyme activity, and alterations in the expression of glutamate receptors. Different neoplasms are associated with different rates of seizures, with oligodendrogliomas having the highest rate of incidence, at 89%–90%, followed by astrocytomas (60%–66%), glioblastomas (31%–40%), meningiomas (29%–41%), and metastases (35%)

(42) .

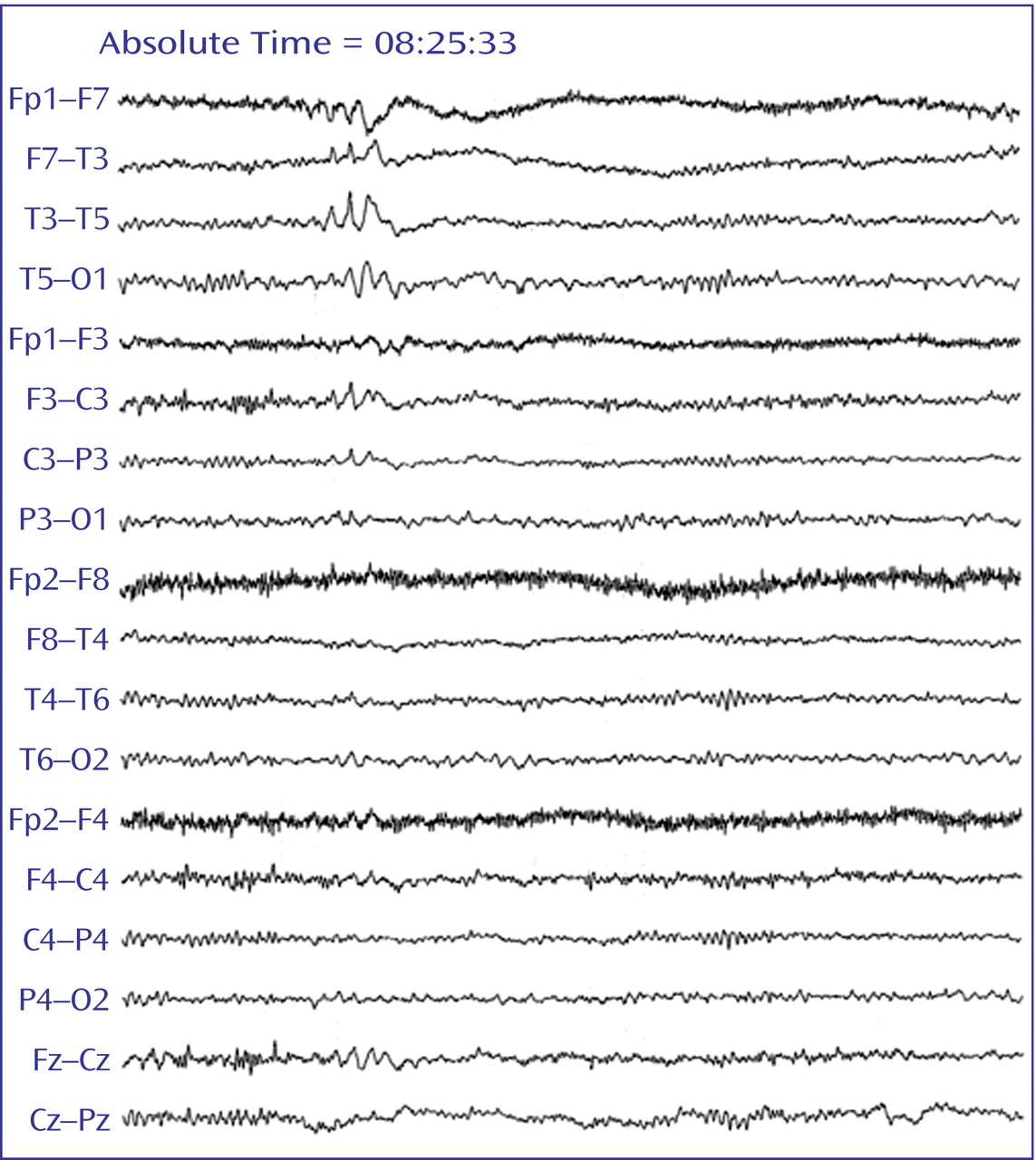

The etiology of Mr. A’s psychosis is likely related to left-side temporal EEG abnormalities, indicating temporal lobe epilepsy. The finding of interictal epileptiform discharges, as seen in

Figure 1, is very specific for temporal lobe epilepsy. Such interictal epileptiform discharges are rare in individuals without a clinical history of seizures, seen in only 0.2%–0.5% of healthy individuals

(43) . Indeed, damage to the temporal lobe appears to be related to the pathogenesis of organic psychosis. Temporal lobe abnormalities are associated with psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease

(11), multiple sclerosis

(44), brain tumors

(8), stroke

(6), and epilepsy

(45) . The etiology of Mr. A’s left temporal lobe dysfunction remains obscure; we know only that the dysfunction exists. None of the imaging modalities employed revealed the presence of a tumor. Could a brain tumor be manifesting as a seizure disorder before becoming detectable with our imaging technology? This would not be unprecedented, but it is impossible to detect at the current time.

The course of Mr. A’s hallucinations best fits the category of interictal psychosis because the occurrence of his hallucinations was sporadic and his cognition remained fully intact during their occurrence. Although interictal psychosis is not usually responsive to anticonvulsants alone

(46) and may likely respond to antipsychotic medicines

(47), Mr. A did not improve until he was administered two anticonvulsants. Treatment response may be related to the specific etiology of the seizures causing the psychotic symptoms, just as different cancer types may have distinct mechanisms of causing seizures.

Although Mr. A’s case is complicated, it highlights the importance of thorough history taking. Mr. A came to the emergency department with a chief complaint of auditory hallucinations. The results of routine laboratory tests and physical examinations were unremarkable, and Mr. A was admitted to the psychiatric service. Psychiatric symptoms, such as psychoses, are clearly nonspecific and are pathognomonic to no specific disorder. Indeed, the list of differential diagnoses is quite extensive. Patients are frequently not aware of their medical conditions. In a study of 658 consecutive psychiatric outpatients, 9.1% were found to have a medical illness as the cause of their psychiatric complaints. In 46% of these cases, the patient was unaware of the presence of the medical condition

(48) .

It is difficult for any physician, particularly primary care physicians, to rule out all possible organic causes. When to order more sensitive and more expensive testing in the search of a rare diagnosis, e.g., a ceruloplasmin test for the diagnosis of Wilson’s disease, is unclear. Studies have questioned the use of even basic brain imaging in psychotic patients. One study at a military hospital—chart reviews of 127 mostly young adult male patients admitted for first-episode psychosis—revealed no abnormal CT scans

(49) . Psychiatrists should reconsider organic etiologies of psychosis when patients have symptoms that do not meet specific DSM-IV criteria, are outside the age range for the usual onset of schizophrenia, are unresponsive to conventional treatment, or have high premorbid functioning with a sudden onset of psychotic symptoms, such as personality changes, decline in functional capacity, or psychosis

(50) . Visual hallucinations are considered to be of organic etiology until proven otherwise

(48) .

In the end, the extensive laboratory tests and brain scans were adjuncts, although helpful, in the eventual determination of Mr. A’s diagnosis. Instead, it was the history obtained from Mr. A’s son regarding the episodic changes in his behavior that offered clues to the existence of seizures. When he was a patient staying on the inpatient psychiatry unit, his doctors did not specifically ask about episodic symptoms, although nurses’ notes included these descriptions: “distracted,” “quiet and distracted,” “more symptomatic in the afternoons,” “appeared distracted,” “unable to make meaningful connections,” and “quiet today.” Each of these may describe a seizure or may represent some postictal confusion.

Instead of noting these behaviors, the psychiatry team focused on Mr. A’s mood and psychotic symptoms. The reverse occurred when he was initially evaluated in the neurology clinic, where the notes merely recorded the absence of “episodes” and did not mention his hallucinations. Because of the nonspecific nature of many psychiatric symptoms and their multiple etiologies, physicians must take extra care to obtain detailed histories, including information from family members and other close observers, and scrutinize these symptom histories with vigilance. This is especially true when one considers a diagnosis of seizures because the patient is often unaware of the occurrence of altered awareness. In the case of Mr. A, a careful history supported by EEG and PET findings led to a diagnosis of seizure disorder.