Advocates for an expanded bipolar disorder construct (i.e., a “bipolar spectrum”) believe that the affective lability and impulsive behaviors characteristic of patients with borderline personality disorder derive from shared genes and that borderline personality disorder should be reconceptualized and reclassified as a part of the bipolar spectrum

(1 –

3) . This thesis is timely as psychiatry strives to develop a nosology in which disorders are grouped into spectrums on the basis of shared etiology

(4 –

6) . It is also appealing because it encourages an optimistic view that patients with borderline personality disorder might benefit from the extensive research on bipolar disorder and that these patients might also prove to be responsive to mood stabilizing medications. Still, as reviewed elsewhere, only a modest body of methodologically sound research to date addresses the interface of borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorders, and of this research, very little supports the thesis of a spectrum relationship between the two disorders

(7) .

Using data from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, we address the interface of borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder, particularly whether borderline personality disorder evolves into bipolar disorder

(8) .

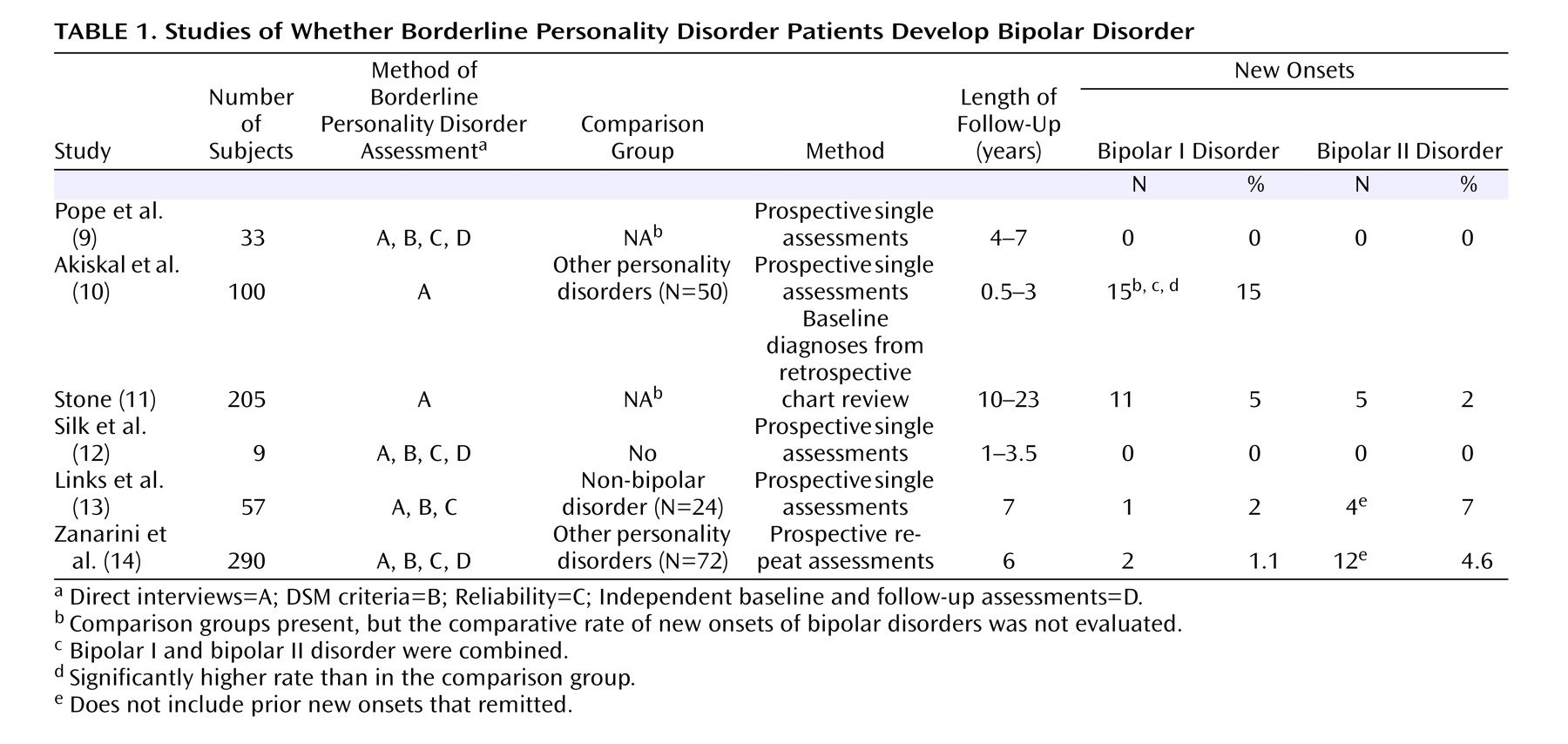

Table 1 summarizes six prior longitudinal investigations of whether borderline personality disorder becomes bipolar disorder

(9 –

14) . The study conducted by Akiskal and colleagues

(10) is notable in that the highest rates of new onsets (i.e., 15%) within 3 years are reported, and their study is the only one to date in which the rate of new onsets was higher than in the comparison group. The two studies with the strongest methodologies (i.e., diagnostic assessments, sample size, length of follow-up) showed fewer new onsets (i.e., 5.7%–9%) and reported no difference from the comparison groups

(13,

14) .

Our study uses a prospective repeated-measures design, reliable and independent diagnostic assessments, 4 years of follow-up, and a comparison group with other personality disorders. This data set was established to determine the following: 1) whether co-occurring bipolar disorder is more common in borderline personality disorder than other personality disorders; 2) whether co-occurring bipolar disorder affects the demographics, comorbidity, treatment utilization, and course of borderline personality disorder; 3) whether borderline personality disorder patients are more apt to develop bipolar disorder; 4) whether new onsets of bipolar disorder occur as an evolution of borderline psychopathology or as sequelae to either neurobiological changes or life event stressors; and 5) whether co-occurring bipolar disorder confers increased risk for developing new onsets of borderline personality disorder.

Results

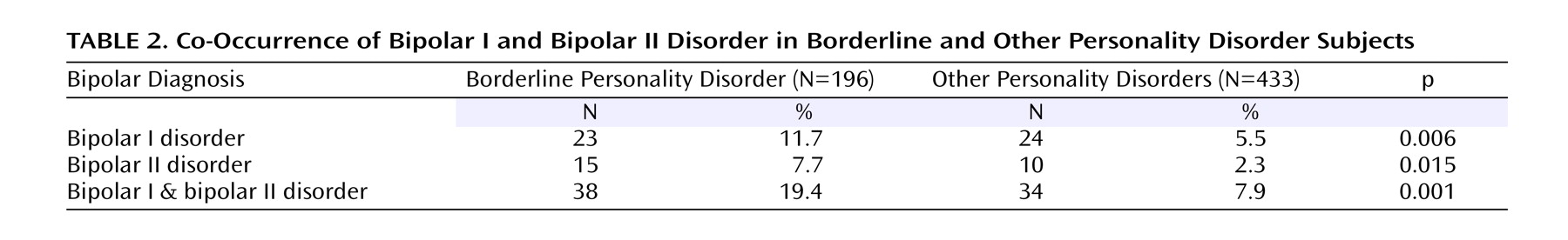

As shown in

Table 2, bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder were significantly more common in patients with borderline personality disorder than in patients with other personality disorders. Comorbid bipolar I or bipolar II disorder occurred in 19.4% of borderline personality disorder patients, versus 7.9% of patients with other personality disorders (χ

2 =17.71, df=1, p<0.001). Bipolar I disorder alone was more common in patients with borderline personality disorder (χ

2 =7.48, df=1, p<0.006) than bipolar II disorder (χ

2 =10.09, df=1, p<0.015).

The presence of comorbid bipolar I or bipolar II disorder had no significant effect on baseline rates of number and types of borderline personality disorder criteria, demographic data, global assessment of functioning, comorbidity, or history of psychiatric hospitalizations. The only significant differences were that patients with comorbid bipolar disorder had, as expected, histories of more use of lithium (32% versus 6.7%, χ 2 =13.36, df=1, Fisher’s exact [two-sided] p<0.0014) and more anticonvulsants (50% versus 17.8%, χ 2 =11.59, df=1, Fisher’s exact [two-sided] p<0.0007). Because of the limited number of bipolar patients, however, only large differences could be detected reliably.

Next, we examined whether the co-occurrence of bipolar I or bipolar II disorder at baseline affected the course of borderline personality disorder. Of the 31 patients with borderline personality disorder with co-occurring bipolar disorder, 66% (N=19) achieved remission by 4 years, which was the same as the 65% (N=89 of 141) for patients with borderline personality disorder without bipolar disorder (Wilcoxon χ 2 =0.0011, df=1, p<0.885). With respect to whether co-occurring bipolar I or bipolar II disorder affected global assessment of functioning scores, we found that global assessment of functioning scores improved over the course of 4 years for patients with borderline personality disorder with or without bipolar disorder. Repeated-measures ANOVA showed no difference by group (Wilk’s lambda F value=0.96, df=4, 138, p<0.44). Repeated-measures ANOVA also showed that co-occurring bipolar disorder had no effect on the number of hospitalizations (Wilk’s lambda F=0.03, df=2, 10, p<0.97). Generalized estimating equations, controlling for baseline usage, showed that co-occurring bipolar I or bipolar II disorder had no significant effect on use of SSRIs (χ 2 =1.28, df=1, p<0.26), other antidepressants (χ 2 =0.01, df=1, p<0.91), neuroleptics (χ 2 =0.66, df=1, p<0.42), or anticonvulsants (χ 2 =0.68, df=1, p<0.41) over the 4 years. The limited use of lithium made this analysis unfeasible.

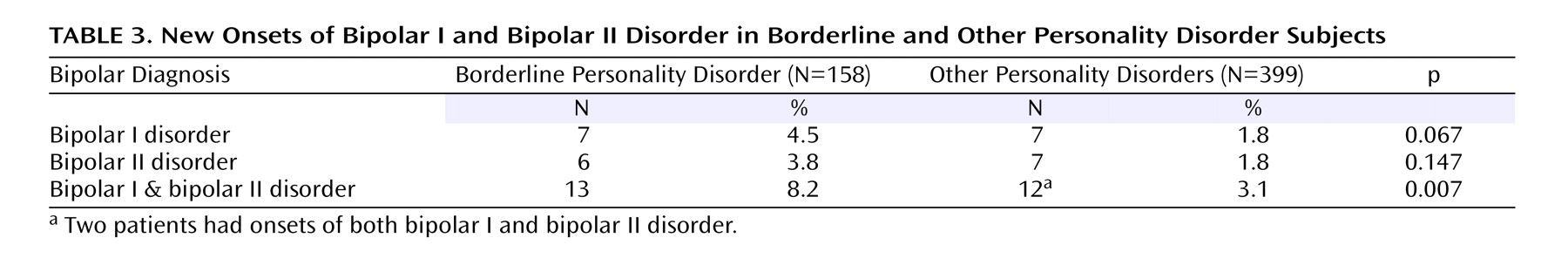

As shown in

Table 3, patients with borderline personality disorder without lifetime bipolar disorder had seven (4.5%) new onsets of bipolar I disorder during the 4-year period. This was a higher rate, although not significantly, than the seven (1.8%) new onsets found in patients with other personality disorders without bipolar (χ

2 =3.36, df=1, p<0.07). The borderline personality disorder patients had six (3.8%) new onsets of bipolar II disorder, which was not significantly higher than the 1.8% rate (N=7 of 399) of bipolar II disorder new onsets in patients with other personality disorders (χ

2 =2.11, df=1, p<0.15). The combined rate of new onsets for bipolar I and bipolar II disorder in the borderline personality disorder group (N=13 of 158, 7.9%) was significantly higher than the 3.1% rate in the other personality disorders group (χ

2 = 7.29, df=1, p<0.007). Of the new onsets, 10 of 13 (77%) for either bipolar I or bipolar II disorder occurred in patients with borderline personality disorder with current or lifetime major depressive disorder at baseline, versus 12 of 14 (86%) in patients with other personality disorders (χ

2 =3.15, df=1, p<0.77). (These respective percentages are somewhat higher than the overall lifetime rate of major depressive disorder in our borderline personality disorder group [60%] or other personality disorders group [59%].)

We examined whether the new onsets of bipolar disorder were preceded by changes in borderline psychopathology, neurobiology, or life events. Our ratings indicated that in no instance did these new onsets follow borderline personality disorder criteria change (either increase or decrease). Six new bipolar onsets followed significant stressful life events; two followed significant neurobiological changes; one followed both stressful life events and neurobiological change; and no precipitants were observed in three.

To examine whether the presence of bipolar I disorder or bipolar II disorder conferred a risk for development of borderline personality disorder, we compared the 277 patients with other personality disorders without comorbid bipolar disorder to the 22 patients with bipolar disorders. The rates of new borderline personality disorder onsets were generally higher in patients with other personality disorder with co-occurring bipolar disorder (i.e., 23%, N=5) than in patients with other personality disorders without co-occurring bipolar disorder (i.e., 10%, N=28) (χ 2 =3.31, df=1, p=0.07).

Discussion

Although our study provides significant improvements in design and methodology, the results should still be interpreted with some degree of caution. For example, although the rate of co-occurrence of bipolar and borderline disorder observed (i.e., the lifetime rates at baseline and new onsets combined brought lifetime co-occurrence to 27.6%) seems high enough to suggest a significant relationship, this may not be the case. Analyses of co-occurrence rates from multiple other studies show that the rate of borderline personality disorder comorbidity in bipolar patients is not higher than for patients with other personality disorders

(7) . Moreover, the rate of bipolar co-occurrence in our borderline personality disorder group is modest compared to the rates found for other disorders (even before following for new onsets). For example, in borderline personality disorder patients, the rates of co-occurrence for major depressive disorder, substance abuse, and PTSD were all more than twice the rate we found for bipolar I and bipolar II disorder

(25,

26) . Finally, because rates of co-occurrence are always elevated in clinical samples, good epidemiological data on the co-occurrence rates of these two disorders in healthy populations are needed before a relationship can be inferred. The validity of diagnosing new bipolar episodes, especially bipolar II disorder, when they are derived retrospectively in follow-up interviews is also problematic

(27,

28) . Thus, this study can offer the reassuring facts that our interviewers were clinically experienced, and they used standardized interviews on which they were well trained and recurrently retrained to avoid rater drift. Moreover, they had no preconceptions or hypotheses that might have biased their efforts to document the manic episodes. These state-of-the-art methods do not prevent mistakes, but they are safeguards against systematic or idiosyncratic bias. A third limitation worthy of comment is the composition of personality disorders in our comparison group (i.e., obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizotypal disorder, and avoidant disorder) that might be expected to have less overlap with the affective and impulsive traits of bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder than would other personality disorders such as antisocial and histrionic personality disorders. Had these latter two disorders been assessed, they might have shed more light on whether borderline personality disorder has a spectrum relationship with bipolar disorder.

The presence of a co-occurring bipolar disorder had no appreciable clinical significance on the clinical course of borderline personality disorder—not in remission rates, functional adjustment, or in treatment utilization as measured by rates of hospitalization and medication usage. The failure of comorbid bipolar disorder to be associated with an altered rate of borderline personality disorder remissions echoes an earlier finding in which major depressive disorder showed only a weak association with borderline personality disorder remissions at 2 years

(29) and none at 3 years

(30) . These results suggest that borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder are not strongly associated disorders.

Our study also shows, however, that patients with borderline personality disorder are significantly more apt to have comorbid bipolar I or bipolar II disorder than patients with other personality disorders and are more apt to have new onsets of bipolar I or bipolar II disorder (when combined, i.e., 7.9%). This rate (i.e., 7.9%) is similar to the rates found by Links and colleagues

(13) and Zanarini and colleagues

(14), and while it is approximately one-half of the rate of onsets found by Akiskal

(31), like Akiskal, it was significantly higher than the comparison group. These findings support the concept of a modest association between borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder. This modest association is also supported by our finding that patients with other personality disorders with co-occurring bipolar disorder showed more new onsets of borderline personality disorder. Still, given the other results in our study and those of other investigators

(7,

32), the modest association that has been observed between borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder is not yet conclusive. Clearly, the new onsets of bipolar disorder did not represent an evolution from borderline personality disorder psychopathology; rather, they most often followed stressful neurobiological or life changes. It remains to be determined whether a neurobiological disposition toward onsets of bipolar episodes was created due to the fact that our borderline personality disorder patients received far more medications than our patients with other personality disorders

(33,

34) .

In summary, our report on the longitudinal course of borderline personality disorder demonstrates a modest association with bipolar disorder. Nonetheless, the evidence in this study for only a small association of borderline personality disorder with bipolar disorder reinforces other results

(29,

30,

35,

36) that have documented a noncyclical, good prognosis course for borderline personality disorder, thereby making a strong spectrum relationship with bipolar disorder extremely unlikely.

Clinical Implications

Despite the fact that these disorders only co-occur in 10%–25% of patients with either disorder

(7), it has become unusual for patients with borderline personality disorder not to have been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, usually bipolar II disorder. The absence of a strong association between borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder, suggested in this study, indicates that clinicians should attend to the differences. Sustained periods of elation, mood lability without evident stressors, or any period of true mania make borderline personality disorder unlikely or secondary. Periods of depression and irritability are rarely instructive. Repeated angry outbursts, suicide attempts, or acts of deliberate self-harm that are reactive to interpersonal stress and reflect extreme rejection sensitivity are axiomatic of borderline personality disorder. In the presence of these symptoms, the diagnosis of a bipolar disorder is unlikely or secondary.

Identifying the co-occurrence of borderline personality and bipolar disorders may be helpful, but the current widespread practice of diagnosing a patient with bipolar disorder and omitting the borderline personality disorder diagnosis has two damaging effects. The bipolar diagnosis encourages patients and their families to have unrealistic expectations about what medications can do. The real—albeit modest—benefits that usually occur when borderline personality disorder is present are then experienced as a failure, which leads to polypharmacy and a growing sense of despair. Moreover, omitting the borderline personality disorder diagnosis diverts therapeutic efforts away from psychosocial interventions that can often make a remarkable difference. Clinicians are frequently reluctant to give patients a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder because it is viewed negatively and is treated most effectively when specialized services that may not qualify for full reimbursement are used. In fact, however, a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder offers patients a reasonable hope for a future that will not require ongoing mental health intervention.