The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study in the 1980s provided the first glimpse of overlapping responsibilities between service sectors

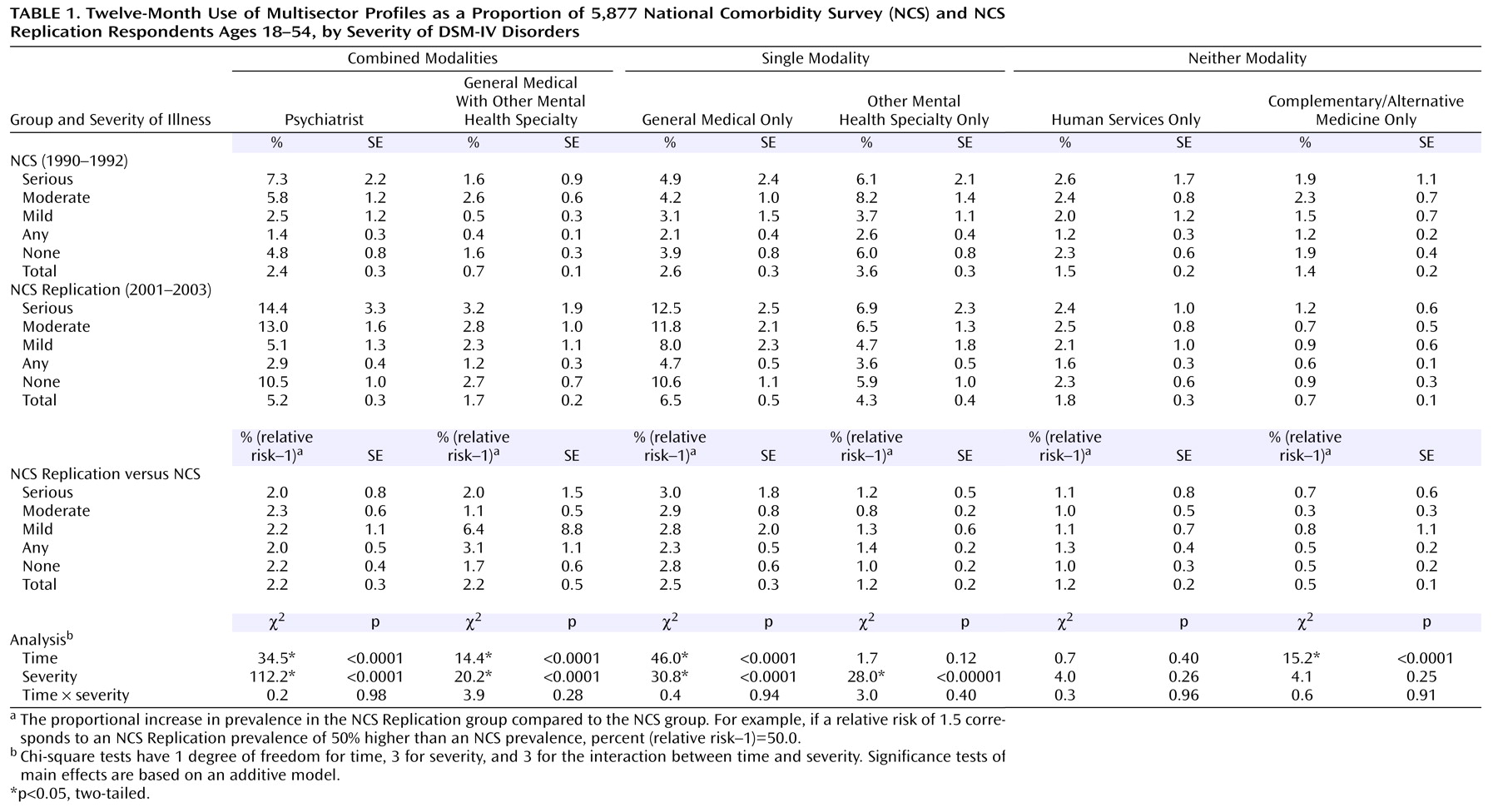

(3) . The general medical sector provided mental health services to 43% of treated patients, including 32% solely. The mental health specialty sector served 40%, including 25% solely, 9% jointly with the general medical sector, and 7.5% with the human services sector. The human services sector provided services to 20%, including 11% solely; self-help sectors served 28%, including 15% exclusively. The National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) a decade later confirmed the fragmented nature of care, with 26% of respondents receiving services from multiple sectors, including 18% from two, 7% from three, and 1% from four sectors

(4) .

In the past decade, overall rates of mental health service use in the United States increased from 12% of the population to 20%

(5,

6) . However, significant increases were limited to the general medical (159%), psychiatrist (117%), and other mental health specialty (59%) sectors. An important next step is moving beyond studying

individual sector use only to more relevant

profiles involving the potential combinations of sectors that people actually use. On one hand, managed care has placed greater emphasis on initial contact in primary care with triage of only more difficult cases to mental health specialists

(7) . Newer medications have also made it easier for general physicians to treat people exclusively with pharmacotherapies, without referral to specialists for psychotherapies

(8,

9) . On the other hand, some

(10,

11) but not all

(12,

13) trials of pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies have shown increased efficacy with joint versus isolated use of these modalities. Data on the questionable safety and effectiveness of no health care have also raised concern over the isolated use of complementary/alternative medical or the human services sector for mental health care

(14 –

17) .

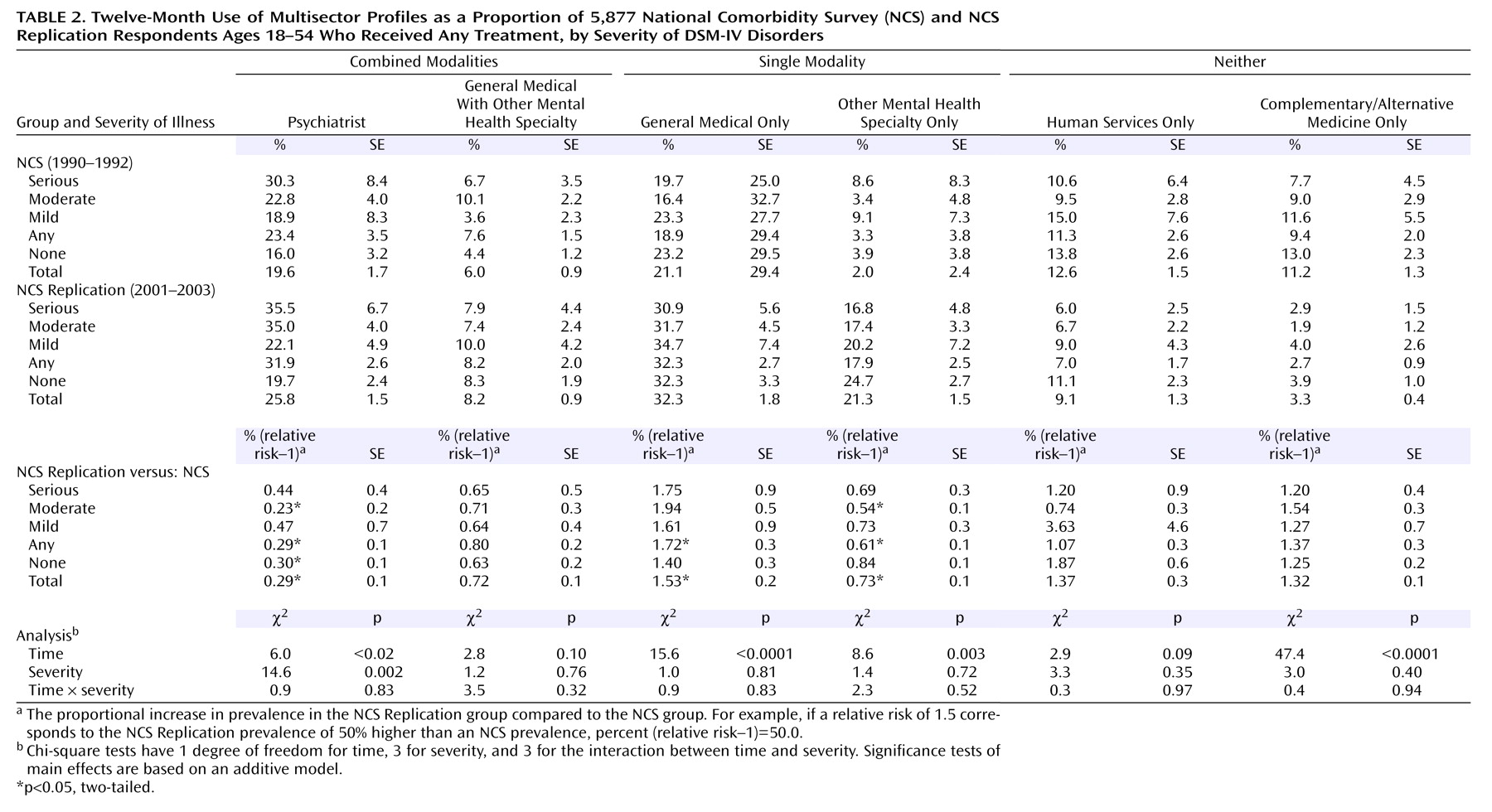

For this article, we used the NCS and NCS Replication to address three aims. First, we sought to move beyond studying

individual sector use to examining the

profiles of care involving potential combinations of sectors that people use and how these have changed over the past decade. We focused on six profiles capable of delivering psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, both, or neither modality. Because using profiles capable of delivering treatments does not necessarily mean those treatments were obtained

(18), we also estimated the extent to which people using services did not receive any active treatment or particular modalities (e.g., combined pharmacotherapy plus psychotherapy). Second, we examined whether the use of specific profiles differed by disorder severity. We did so in light of the greater needs for effective treatment among serious cases and evidence that combined modalities are especially beneficial for them

(10,

11) . Third, we identified predictors of using different profiles to inform efforts to redesign and reorganize the U.S. mental health care system.

Method

NCS and NCS Replication Samples

The original NCS, conducted between 1990 and 2002, was a nationally representative household survey of 8,098 respondents ages 15–54

(4) . A part I diagnostic interview was administered to all respondents, and a part II risk factor interview was administered to a probability subsample of 5,877 respondents who screened positive for mental disorders and a random subsample of the remaining part I respondents (response rate=82.4%).

The NCS Replication in 2001–2003 employed a nationally representative sampling scheme that differed from the NCS in three ways: 1) respondents ages 15–17 were not included, 2) the age range included those 55 and older, and 3) a second respondent was selected in 25% of the households to study within-household aggregation of disorders

(19) . The respondents completed a part I diagnostic interview (N=9,282), and a probability subsample completed a part II risk factor interview (N=5,692) (rate of response=70.9%).

Data from both surveys were weighted for differential probabilities of selection, nonresponse, and discrepancies with U.S. Census population distributions on demographic and geographic variables

(20 –

22) . After a complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Recruitment and consent procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of the University of Michigan and Harvard Medical School (the latter only for the NCS Replication).

Presence and Severity of DSM Mental Disorders

The NCS and NCS Replication made DSM-III-R and DSM-IV, respectively, diagnostic assessments based on the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)

(23) . Both DSM versions assessed anxiety (panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, phobias, and posttraumatic stress disorder), mood (major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and bipolar disorder), and substance use disorders (alcohol and drug abuse and dependence). Good concordance has been observed between most CIDI–diagnosed disorders and blind clinician diagnoses made with the Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-III-R or DSM-IV

(22,

24) .

NCS Replication respondents who reported 12-month DSM-IV disorders were asked to focus on the month in the past year when symptoms were most persistent and severe and to rate role disability during that month. Sheehan Disability Scale

(25) responses were used to define a severity gradient. Seriously ill subjects met criteria for the following: bipolar I or nonaffective psychosis, a suicide attempt or psychiatric hospitalization in the past year, three or more areas of “severe” or “very severe” Sheehan Disability Scale role impairment (i.e., a domain score of 9 or 10), three or more areas of at least “medium” Sheehan Disability Scale role impairment (i.e., a domain score of at least 7 or 8), plus at least four mental disorder diagnoses or more than 5 days of hospitalization or a multivariate functional impairment score equivalent to a Global Assessment Scale score

(26) of less than 55. Moderate cases were defined as those having at least “moderate” interference from a mental disorder in any Sheehan Disability Scale life dimension (i.e., a domain score of 4 or greater). All other disorders were classified as mild. In a previous examination of the validity of these ratings

(6), a significant gradient was found in average days out of role reported by patients with serious, moderate, and mild cases.

For NCS respondents, comparable aggregate estimates of disorder presence and severity were developed in nested logistic regression equations that used symptom measures available in both the NCS and NCS Replication to predict the following: 1) serious disorders versus all others, 2) serious-to-moderate disorders versus mild disorders or no disorder, and 3) any disorder (i.e., serious, moderate, or mild) versus no disorder. These were estimated only in the NCS Replication because the measures of seriousness were not available in the NCS. Areas under the receiver-operating characteristic curves indicated good predictive validity

(6) .

Multisector Profiles of Care

The respondents to part II of the NCS and NCS Replication were asked whether they ever received mental health services and, if so, whether in the previous 12 months they used providers in each of the following five mutually exclusive service sectors: a psychiatrist; another mental health specialist, including a psychologist or other nonpsychiatrist mental health professional in any setting, a social worker or counselor in a mental health specialty setting, or mental health hot line workers; the general medical sector, including a primary care doctor, another general medical doctor, a nurse, or any other health professional not mentioned; human services, including a religious or spiritual adviser or a social worker or counselor in any setting other than a specialty mental health setting; and complementary/alternative medicine, including any other type of healer or participation in a self-help group.

Based upon their use of individual sectors, we then defined whether the respondents had used six mutually exclusive profiles of care involving potentially multiple sectors. Two profiles capable of delivering combined pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies were the following: the psychiatrist profile (defined as any use of the psychiatrist sector) and the general medical with other mental health specialty profile (defined as use of the general medical plus other mental health specialty sectors without use of the psychiatrist sector). Two profiles capable of delivering single modalities were the following: the general medical only profile (defined as use of the general medical sector without psychiatrist or other mental health specialty sectors) and the other mental health specialty only profile (defined as use of the other mental health specialty sector without the psychiatrist or general medical sectors). Finally, two profiles in which neither modality is likely to have been received were the following: the human services only profile (defined as use of the human services sector without a psychiatrist, another mental health specialty, or the general medical sectors) and the complementary/alternative medicine only profile (defined as use of the complementary/alternative medicine sector without any other sector).

The respondents who made only one visit to any sector, received no psychiatric medications, and were not in ongoing treatment at their interviews were considered to have obtained no active treatment. The respondents were considered to have obtained combined psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy if they either 1) made eight or more visits to a provider and received a medication or 2) reported being in ongoing treatment at their interviews.

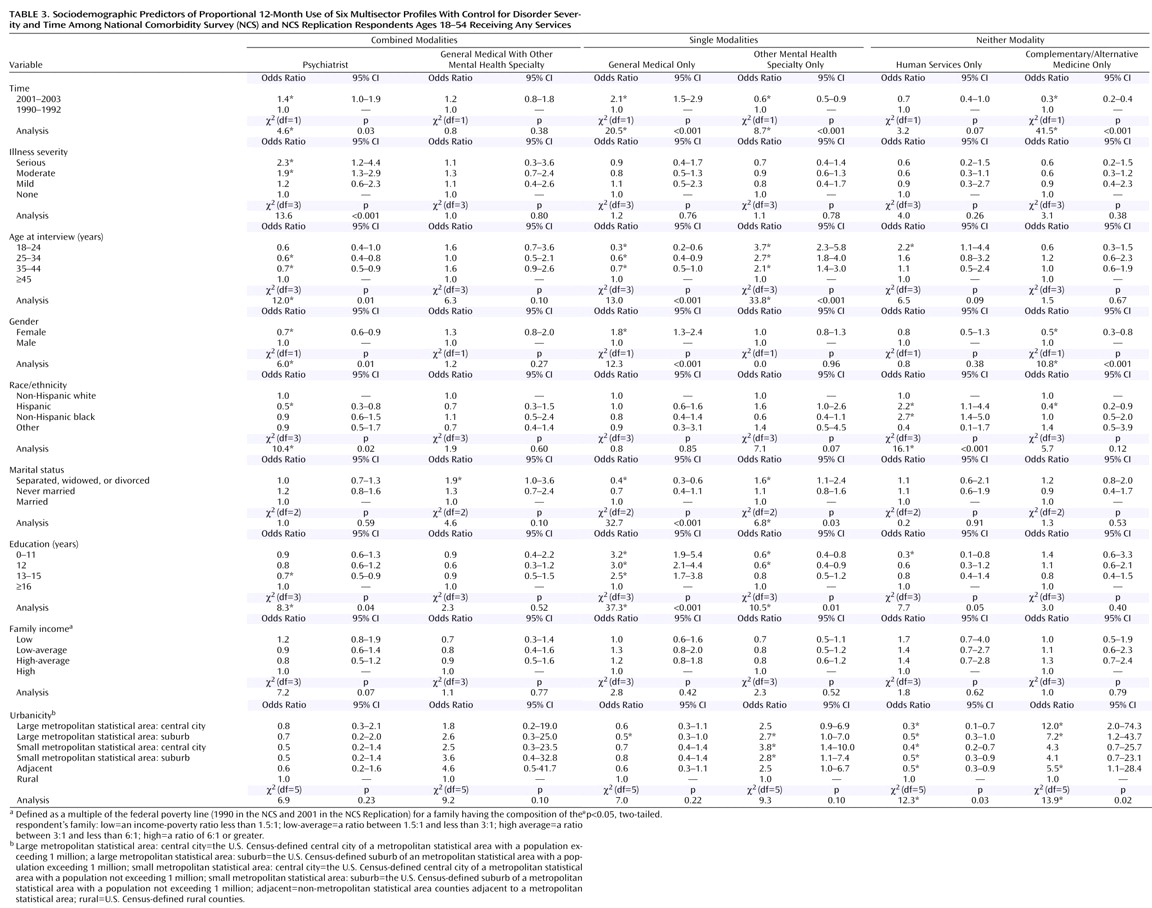

Sociodemographic Correlates

The NCS and NCS Replication asked identical questions to assess age (18–24, 25–34, 34–44, and 45–54 years), sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other), marital status (married or cohabiting, previously married, or never married), education (0–11, 12, 13–15, and 16 years or more), household income, and urbanicity. Income was defined as a multiple of the federal poverty line accounting for the composition of the respondent’s family, with low income defined as an income-to-poverty ratio of less than 1.5:1; a low-average income ratio in the range of 1.5:1 to less than 3:1, a high-average ratio in the range of 3:1 to less than 6:1, and a high ratio of 6:1 or greater. Urbanicity was defined with the 1990 (NCS) and 2000 (NCS Replication) U.S. Censuses as large (at least 2 million residents) and small metropolitan statistical areas, central cities and suburbs within metropolitan statistical areas, adjacent areas (areas outside the suburban belt but within 50 miles of the central business district of a central city of a metropolitan statistical area), and rural areas (areas more than 50 miles from the central business district of a central city).

Analysis

The weighted part II data for respondents ages 18–54 were merged. Although some profiles are defined by use of a single sector (e.g., the psychiatrist profile), our analyses focused exclusively on those profiles involving potential combinations of sectors, not on individual sector use. We compared the NCS and NCS Replication for use of each of the six profiles of care defined. Differences were assessed in the overall sample and separately in serious, moderate, mild, and subthreshold 12-month cases. Statistical significance was evaluated by using z tests for the differences in prevalence estimates. Combined data from the two surveys were also used to estimate a series of logistic regression equations predicting use of specific profiles. Standard errors of all prevalence estimates and all logistic regression coefficients were obtained using the Taylor series linearization method

(27) implemented in SUDAAN

(28) .

Discussion

Three sets of limitations should be kept in mind. First, although the methods, instruments, and sector classifications were kept largely the same between the NCS and the NCS Replication, the internal validity of responses could have been affected by even subtle differences in surveys, nonresponse, and nonreporting. For example, mental disorders were assessed differently, and imputation was employed to ensure comparable estimation of prevalences over time. The accuracy of these imputations is supported by strong associations between imputed and direct assessments in the NCS Replication.

Second, we cannot be certain whether those using profiles actually obtained any treatment, particular modalities, or adequate care. Our crude lower-boundary estimates suggested that at least 10%–15% of those using services fail to receive any active treatment. Among those using profiles capable of delivering combined psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy, perhaps the minority actually obtains these modalities. Even those receiving pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies often fail to receive regimens that meet minimal thresholds for adequacy

(18,

29) . As a consequence, the actual number of patients who receive evidence-based pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies is likely to be much smaller than those with the potential to do so based on their profile use.

Finally, the external validity of these results may be limited because the sampling frame excluded people in institutions as well as the homeless and did not span all diagnostic categories. However, such restricted sampling frames have been shown to exclude only a small proportion of mentally ill people, and clinical reappraisal interviews have found that a vast majority of serious cases are detected by the NCS Replication interview

(21) .

With these potential limitations in mind, this study sheds light on both the complexity of the U.S. mental health care delivery system as well as important shifts in the combinations of service sectors that individuals use. The general medical only profile experienced the largest growth over the past decade and is now the most common profile. This increased use of general medical providers without specialists may be because primary care physicians now act as “gatekeepers” for nearly one-half of patients

(30) . The provision of mental health care in general medical settings has also been improved through greater understanding of how mental disorders present and the design of primary care screening tools

(31,

32) . The development and heavy promotion of new antidepressants and other psychotropic medications with improved safety profiles have further spurred care of mental disorders exclusively in general medical settings

(8,

9) . There has also been a growing tendency for some primary care physicians to deliver psychotherapies themselves

(33) .

Two aspects of this expanded use of the general medical only profile warrant concern. One is that it has occurred equally for people with severe as well as less severe disorders. This is worrisome in light of growing evidence favoring combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for patients with serious disorders

(10,

11) . In addition, general medical care without specialty use may result in lower treatment intensity and adequacy than in specialty care

(29,

34) .

The psychiatry profile is now the second most commonly used profile and also one experiencing growth during the last decade. On one hand, this may seem surprising, given both cutbacks in spending for specialty care as well as warnings by psychiatrists that managed care and gatekeeping would lead to diminished use of their services

(32) . This increase may reflect factors similar to those responsible for greater use of nonpsychiatrist physicians, including diminished stigma, greater recognition of the need for mental health treatment, and greater availability and demand for pharmacotherapies

(5,

6,

35) .

However, it is disconcerting that the temporal increase in use of the psychiatrist profile has not particularly benefited patients with serious conditions. The psychiatrist profile is one of two examined in which combined modality treatment could have been received. As mentioned, evidence has been growing that dual-modality treatments are especially beneficial to those with more serious disorders

(10,

11) . The general medical with mental health specialty profile was the other one from which combined modality treatment could have been received. Unfortunately, it was used only modestly and did not increase between surveys. The fact that it, like the psychiatry profile, was not more likely to be used by severely ill patients raises further questions regarding whether dual-modality treatments are being optimally allocated.

The other mental health specialty only profile, representing possible use of psychotherapy alone, had been the most popular profile in the NCS but declined significantly in the past decade. This finding is consistent with a significant decrease in psychotherapy visits during the 1990s

(5,

33) . It could reflect new restrictions on the number of psychotherapy sessions, increased patient cost sharing, and reduced provider reimbursements for psychotherapy visits imposed by many third-party payers

(36) . It could also reflect changes in the popularity of therapeutic modalities, particularly patients’ growing preferences for psychotropic medications

(5) .

Decreasing use of the human services only profile may be part of a longer-term decline in the use of the clergy for mental health care

(37) . Recent cutbacks in funding and programs in social services agencies may also be contributing to the declining use of this profile

(36) . Use of the complementary/alternative medicine only profile also decreased dramatically, perhaps in response to accumulating evidence that these treatments may lack efficacy or pose safety problems

(14,

15) .

Younger cohorts’ greater use of profiles capable of delivering psychotropic medications (the psychiatrist profile or the general medical only profile) could reflect the particular popularity and successful promotion of these agents to younger people

(5,

9) . By contrast, the older cohorts’ reduced use of profiles employing psychotherapy exclusively may reflect an unacceptability of this modality to the elderly

(38) . Our observation that women receive fewer psychiatric services but more general medical services for mental health care than men is consistent with earlier findings that primary care physicians are more willing to treat women but tend to refer men to specialists

(39) . Racial and ethnic minorities’ greater reliance on the human services only profile may reflect their ease of access to religious leaders or social services agencies, as well as prior experiences of prejudice and mistreatment within profiles involving health care sectors

(16,

17,

40) .

Nonmarried peoples’ greater use of profiles capable of delivering exclusively psychotherapy and their reduced use of profiles capable of delivering pharmacotherapy exclusively may indicate that counseling is a preferred modality for relational difficulties

(41) . Education’s positive relationship with profiles potentially employing psychotherapies and negative relationships with profiles potentially employing pharmacotherapies exclusively may reflect an importance placed on knowledge and cognitive processes in many psychotherapies

(42) . Urbanicity’s positive association with the complementary/alternative medicine only profile and its negative association with the human services only profile may be due to structural realities that few complementary/alternative medicine sources are found outside urban areas, whereas religious and social services may be the only resources available to rural residents

(43) . The fact that use of the human services without health care only profile did not decline in rural as in urban areas may further indicate the reliance on religious leaders for mental health needs among rural residents.

These results clearly confirm key observations made by the president’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health: that the U.S. mental health care system remains fragmented and that this complexity may be contributing to many Americans failing to receive the treatments they need

(2) . Although this analysis primarily focused on fragmentation of care

across sectors, the commission also recognized the equally important fragmentation that can occur

within sectors because of the variety of competing clinical (e.g., mental health versus general medical), social, and human service needs that many patients and their clinicians experience

(44) .

Beyond documenting these realities, what can be done to address both types of fragmentation and help ensure that Americans with mental health needs receive effective care? In considering this difficult question, the commission recommended overcoming obstacles posed by fragmentation by meeting six goals. The commission’s first goal—increasing American’s awareness of their mental health needs—will almost certainly require renewed educational and awareness campaigns to promote the public’s recognition of disorders and profiles for which effective care can be received

(7) . Another goal—early detection and treatment—would benefit from additional application of screening programs as well as timely referrals from profiles involving exclusively non-health-care-providers to those involving health care professionals

(31,

32,

45) . The goal of increasing high-quality consumer-oriented care will likely require expansion of treatment resources as well as demanding greater accountability for the outcomes resulting from the use of different profiles

(46) . Eliminating current disparities in service use suggests that such initiatives and resources should be focused on traditionally underserved groups, including racial and ethnic minorities and rural communities

(47) . Final goals call for increased undertaking of best practices that optimally employ generalists, specialists, and health technology. Such interventions may be especially needed to address

within -sector fragmentation from competing clinical, social, and human service demands on clinicians’ limited time and resources. Several disease-management models that employ allied health personnel and innovative decision-support systems to assist beleaguered clinicians have already proven to be effective and may deserve wider dissemination

(48 –

52) . Recent legislation suggests that the public may already be willing to pay for such programs to ensure that Americans receive effective care

(53) . Parallel efforts to define return on investments are needed to generate analogous support among employer purchasers for model programs that help transform the fragmented U.S. mental health care delivery system

(37) .