The National Survey on Drug Use and Health

(1), the Monitoring the Future study

(2), and the Drug Abuse Warning Network Report

(3) have cited significant increases in prescription opioid use over the past 5 years, particularly among young people. The causes for this increase are unknown; however, the leadership of the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy have both expressed concern that online pharmacies selling medications without prescriptions may be playing a role

(4,

5) . “No prescription” web sites (NPWs) advertise the availability of prescription medications over the Internet without a legal prescription. The U.S. General Accounting Office reported on June 17, 2004, that it successfully purchased opioid medications, including oxycodone and hydrocodone, without prescriptions from 10 of 11 web sites

(6) .

The Internet complicates enforcement of the U.S. Controlled Substances Act because U.S. customers can make purchases from online pharmacies hosted in countries that do not require prescriptions to sell opioid medications or do not enforce prescription regulations that are in effect in the U.S.

(7) . This compromised enforcement of the Controlled Substances Act removes health care professionals from the prescription process, introducing additional risk for drug misuse, abuse, dependence, and overdose. Of particular concern is the role that NPWs might play in initiating opioid use among young people; individuals who are 21 years and younger are the most frequent users of the Internet

(8) and are in the age group in which drug use typically begins

(9) .

Very little is known about the availability of NPWs, their characteristics, or the degree to which they contribute to drug abuse. This lack of basic information compromises the ability of the public health system to develop and initiate appropriate prevention, intervention, and treatment measures. The development of reliable NPW monitoring methods and basic knowledge about NPWs are critical first steps in developing a public health response to what appears to be an Internet-borne means for spreading substance use, abuse, and dependence.

The Internet

With approximately 200 million Internet users in the United States and more than 125 million individuals going online every week

(10), the Internet is a vital medium for communication, entertainment, and commerce. The Pew Internet and American Life Project

(8) reported that 100% of college students, 78% of 12–17-year-olds, and 63% of all adult Americans are online at least once a month. Like television, radio, and print media, the Internet provides the public with information, entertainment, and advertisements. The Internet differs from all other media, however, in at least one important way: it enables customers from around the world to shop with relative anonymity in a 24-hour marketplace.

The benefits of the Internet apply equally to everyone, including individuals who commit unlawful acts, such as software privacy, virus release, identity theft, espionage, and the sale of child pornography, illegal weapons, and controlled substances

(11) . Online stores can be hosted and registered anywhere in the world, advertising, selling, and delivering products with relative anonymity and convenience—with little regard for the laws of other countries. The U.S. Controlled Substances Act prohibits the sale of schedule I drugs, such as marijuana, heroin, psilocybin, crack cocaine, and Ecstasy, and regulates access to schedule II–V drugs, including opioids, sedatives, stimulants, and steroids, by requiring a valid prescription from an appropriately licensed health care professional

(7) . Many countries have drug policies that differ from those of the United States or have similar laws but less enforcement. Individuals wishing to sell drugs such as opioid medications to customers in the United States can do so through NPWs registered and operated outside the United States. These web sites can be identified through Internet searches with terms such as “Vicodin” or “no prescription,” potentially enabling customers of any age to purchase opioids from an international network of online pharmacies.

On July 30, 1999, a U.S. Deputy Associate Attorney General testified before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, Commerce Committee, U.S. House of Representatives, that “online pharmacies allow consumers to purchase prescription drugs without any pretense of a prescription” and that these web sites introduce “potential risks to public health and safety”

(12) . A week later, the White House issued Executive Order 13133, creating the Working Group on Unlawful Conduct on the Internet, leading to the publication of “The Electronic Frontier”

(13) . The Drug Enforcement Administration subsequently published guidance

(14) that specified four conditions under which legal prescriptions can be issued over the Internet: 1) a patient presents a medical complaint, 2) a medical history is obtained, 3) a physical examination is performed, and 4) some logical connection exists between the medical complaint, the medical history, the physical examination, and the drug prescribed. Prescriptions based on telephone interviews or online questionnaires are not considered valid. In support of these guidelines, the American Medical Association subsequently issued guidance for physicians on Internet prescribing that largely parallel’s the Drug Enforcement Administration’s position

(15) .

Method

To determine the availability of web sites offering to sell opioid medications without a prescription and to develop basic knowledge about the parameters affecting the types of web sites obtained in searches, the investigators conducted a series of related studies.

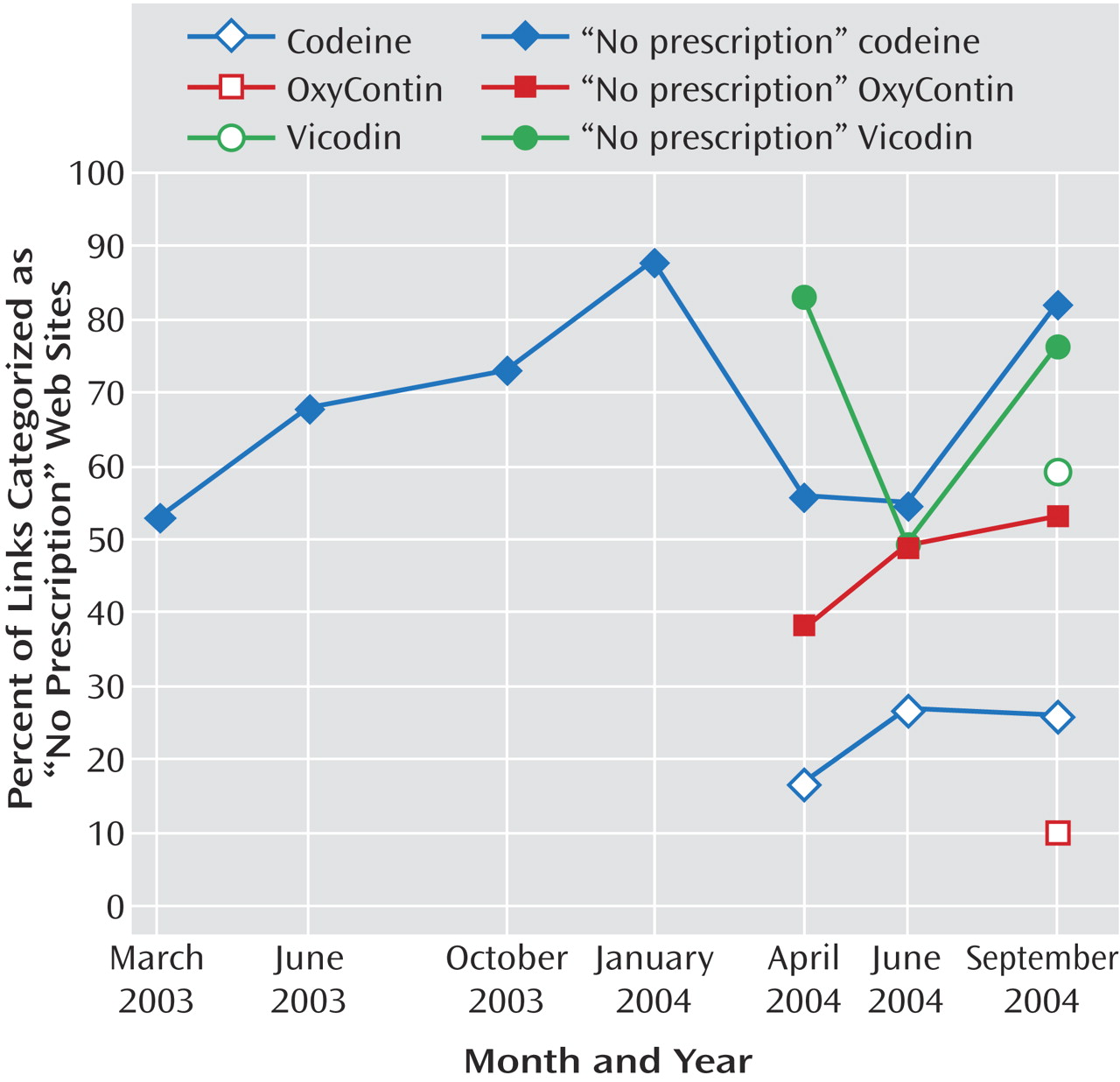

Method 1: “No Prescription Codeine”

Between March 3, 2003, and Sept. 7, 2004, seven NPW monitoring studies were conducted as follows. Two raters independently examined the first 100 links generated in Google searches with the term “no prescription codeine.” Each resulting link was categorized as an NPW if it contained a hyperlink to a web site offering to sell a scheduled opioid medication without a prescription either directly (“retail”) or indirectly through a portal web site. All other links were categorized as either “information” if it provided information about opioids, drug use, or drug treatment or “other” if it was 1) a legitimate online pharmacy, 2) a broken link, or 3) any other type of link (e.g., a link to the web site of a rock band named Codeine). Portal web sites provide links to multiple retail NPWs.

The first rater prepared a spreadsheet with the following data fields: 1) the web site’s name, 2) its URL, 3) the categorization of the web site (e.g., retail, portal, information, or other), 4) whether the web site was a duplicate of a previously identified site, and 5) the country in which the web site was registered. The second rater independently repeated the categorization process of coding of the links. These two ratings were then compared and discrepancies reconciled by viewing the links together and reaching a consensus. Web site advertisements were not included because advertised links are not included in Google’s PageRank method

(33) .

Method 2: Expanded Opioid Search Terms

Eleven additional NPW searches were conducted between April 15, 2004, and Sept. 7, 2004, with procedures identical to those described above but with alternative drug search terms: “no prescription Vicodin,” “no prescription OxyContin,” “Vicodin,” “OxyContin,” and “codeine.”

Method 3: Relative Availability of Addiction Health Information

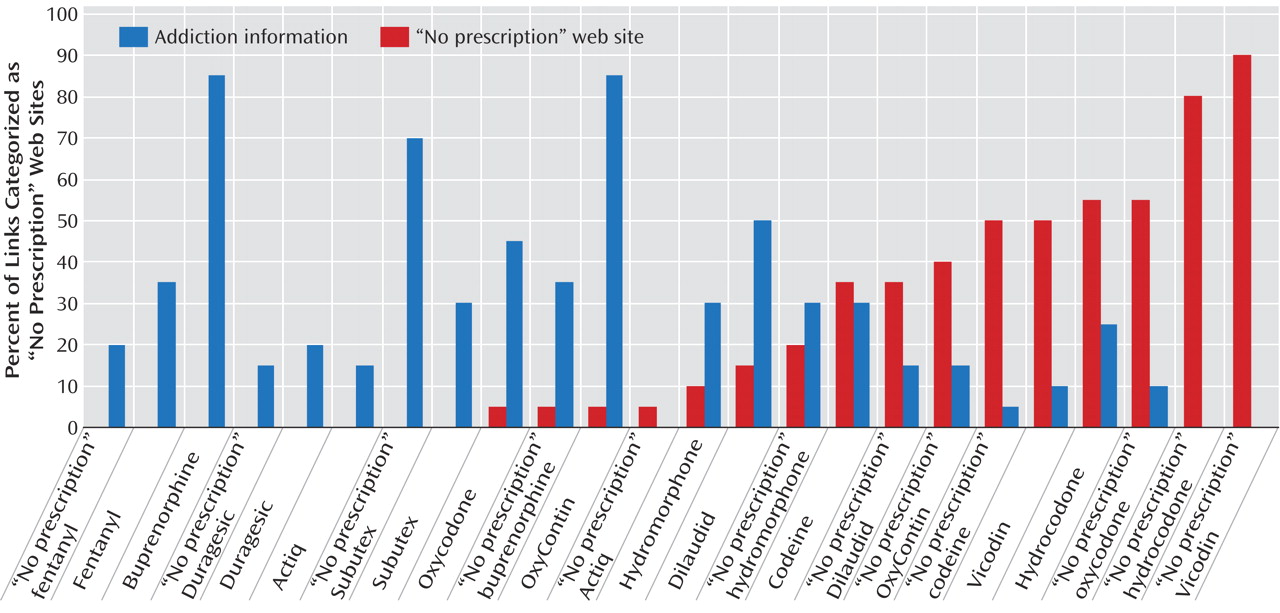

During the first 2 weeks of August 2004, searches were conducted with 27 opioid search terms; the procedures employed were identical to those previously described, except only the first 20 links were examined for each term. Search terms included 1) generic opioid medication names (e.g., “hydrocodone”) and 2) opioid medication brand names (“Vicodin”). For each generic and brand-name opioid, additional searches were conducted with the prefix “no prescription” (e.g., “no prescription hydrocodone”). The resulting web sites were categorized as before except that a new coding category was added: web sites that specifically provided “addiction health information” (e.g., http://www.nida.nih.gov).

Method 4: Comparison of Google and Yahoo

With the NPW coding procedures described, the first 100 links obtained with the term “no prescription Vicodin” were determined with both Google and Yahoo for searches that were conducted in the same week in September 2004 by the two independent raters.

NPW Database

Starting on Jan. 2, 2003, information about each NPW identified in NPW monitoring studies was entered into a database with the following data elements: 1) web site name, b) URL (e.g., www.OxyContin.com), 3) categorization of link (portal, retail, information, other, and whether the link was a duplicate of a previously identified link), 4) date of search, 5) comments (e.g., “web site states it temporarily ceased operations”), and 6) country in which the opioid medication’s NPW was registered. By querying a domain registration service (www.register.com), the investigators were able to determine the country in which each web site was registered. Web site registration indicates the “official” location of the business but not necessarily the nationality of the web site owner.

Discussion

These NPW studies were intended to replicate what Internet users would encounter if they conducted searches for information about opioid medications and/or for the availability of these medications without a prescription. Together these 47 Internet-based monitoring studies indicate that web sites offering to sell opioid medications without a prescription are pervasive and, in many cases, more prevalent than sites simply providing information. Coupled with the General Accounting Office’s study documenting that NPWs do deliver opioid medications without a prescription

(6), it appears as if the Internet has increased and facilitated the availability of these medications.

The consistency with which our searches yielded NPWs indicates that their availability has been relatively stable, at least since March 2003. Our ongoing research includes continued monitoring of the availability of NPWs offering to sell opioids as well as other classes of controlled substances to assess whether availability changes over time. Continued monitoring of NPWs will make it possible to assess the effectiveness of new enforcement and regulatory efforts at eliminating or reducing the availability of NPWs.

NPW monitoring studies in which the first 100 links were examined have provided a relatively large sample of web sites that individuals may encounter when conducting opioid searches; however, people are unlikely to examine 100 links if they can find what they are seeking in the first 10 or 20. The finding that NPWs were more densely populated among the first 20 links is important since it may provide a better reflection of people’s actual experience on the Internet.

The use of the search prefix “no prescription” consistently increased the percent of NPWs obtained, suggesting that this may be a more sensitive monitoring strategy. By increasing the sensitivity of our search strategies, emerging tendencies in the availability of prescription drugs over the Internet may be enhanced. In future NPW monitoring studies, investigators should consider including alternative search terms, such as the “no prescription” prefix.

In our exploratory study examining the availability of addiction health information, it was notable that the “no prescription Vicodin” and “no prescription hydrocodone” searches yielded 80% and 90% NPWs, respectively, and no web sites offering addiction health information; given that 10% of all high school students reported using hydrocodone in the past year

(2), prevention researchers and interventionists might consider efforts to increase the visibility of prevention messages on the Internet, particularly keyed to the most frequently abused substances.

In our single comparison of the two leading search engines, Yahoo generated significantly more NPWs than Google. Because all of our prior studies used Google, it is possible that the findings reported here underestimate the relative availability of NPWs when other search engines such as Yahoo are used.

It is important to recognize the limitations of these studies. First, unlike the General Accounting Office investigation

(6), we made no effort to purchase opioids from the NPWs identified in our searches. We do not know what proportion of these web sites actually deliver opioid medications without a prescription. It is possible that the high delivery rate obtained by the General Accounting Office does not apply to the web sites identified in our studies. Future research should assess the proportion of NPWs that actually deliver the medications as advertised.

A second limitation of the current study was its narrow focus; by limiting our searches to opioid medication terms, we hoped to develop a better understanding of one class of NPWs. However, in the course of these and other searches, we have found web sites offering to sell a diverse range of scheduled substances, including sedatives, stimulants, steroids, other opioid analgesics (such as fentanyl), marijuana, opium poppies, coca leaves, nitrous oxide, psilocybin, and peyote. To date, we have found no web sites offering to sell Ecstasy, LSD, heroin, or cocaine. Research is needed to assess the availability of web sites offering to sell controlled substances in addition to opioids.

Search engines such as Google make NPWs readily available to the public without any medical guidance or control. This unregulated access is likely to increase use and contribute to abuse, dependence, and overdose. Young people—the heaviest users of the Internet

(34) —appear to now have an unsupervised means of obtaining opioid medications. Although law enforcement agencies have been aware of these web sites since 1999, their availability does not appear to have diminished. Uncontrolled access to prescription opioids introduces a unique development with potential broad implications for law enforcement, health care delivery, and drug policy.