Discussion

Assessments of decisional capacity to provide informed consent for, or refusal of, medical treatments, to leave the hospital against medical advice, or to manage a variety of living situations are among the core clinical tasks of consultation-liaison psychiatrists

(1,

2), accounting for an estimated 3%–8% of all requests for psychiatric consultation

(3) . Evaluation of cognitive functioning has been the cornerstone of capacity assessments, particularly in patients with current or past psychiatric disorders, for several reasons. First, formal thought disorders are a cardinal symptom of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia

(4,

5) . Second, impairments in cognitive functioning, such as loss of remote or recent memory, and problems with executive functioning are the clinical hallmarks of dementia, a condition frequently encountered on medical-surgical wards and in nursing homes

(6) . Third, most of the high-quality research on decisional capacity assessment has been done in a research context, and given ethical and legal requirements for informed consent, it has been cognitively based. Translations of research measures and methods to the clinical setting, in turn, have naturally maintained the cognitive approach

(7 –

9) .

These cognitively based assessments have substantially improved the rigor, clarity, and standardization of decisional capacity evaluations for research and treatment. They remain the essential first step in exploring the capacity of any patient to consent to treatment. However, noncognitive dimensions of decisional capacity may also be significant and require attention, especially in cases where no serious or overt cognitive dysfunction is detected through bedside or formal neuropsychological testing. Several authors have suggested that emotional capacities, such as appreciation, and volitional components, such as voluntarism, have been historically neglected in the research and practice of capacity determination and merit further research and clinical development

(10 –

12) .

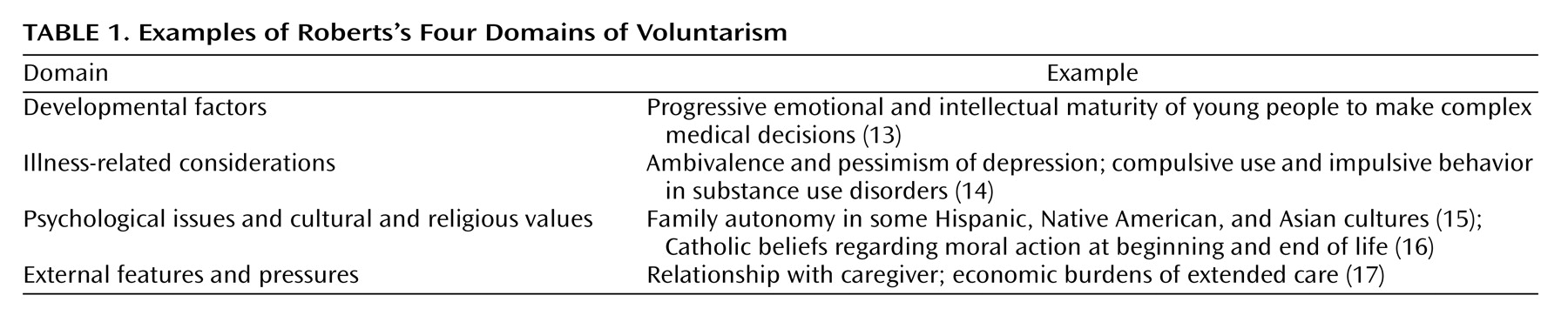

Roberts has explored the capacity for voluntarism as it pertains to informed consent

(12) . She defines voluntarism as “the individual’s ability to act in accordance with one’s authentic sense of what is good, right, and best in light of one’s situation, values, and prior history.” Voluntarism, she says, encompasses the classical exercise of free will or self-determination understood as the absence of excessive internal or external coercion. Roberts identifies “deliberateness, purposefulness of intent, clarity, genuineness, and coherence with one’s prior life decisions” as qualities of an authentically voluntary decision

(12) . She cites four domains of influence that can potentially enhance or diminish voluntarism: developmental factors; illness-related considerations; psychological issues and cultural and religious values; and external features and pressures.

Table 1 provides examples of each domain.

The case presented illustrates the benefit of an assessment of voluntarism that is integrated with classical evaluations of cognitive capacity and demonstrates a clinical application of Roberts’s construct in the practice of consultation-liaison psychiatry. Neuropsychologically based assessments of Mr. B’s ability to provide informed consent disclosed no significant deficits in the gold-standard measures—capacity to understand, reason, appreciate, or communicate regarding the clinical facts and treatment choices

(18) . Yet the clinicians and the consultants alike sensed a lack of consistency, authenticity, and intentionality, which are the hallmarks of deliberate, free, cohesive expressions of self-determination

(19) . Exploring the voluntarism aspects of this case illuminated previously undetected features of the clinical contexts that contributed to impairments in volitional capacity, which in turn compromised the patient’s ability to provide informed consent. These insights enabled the treatment team to develop plans that could address and substantially improve Mr. B’s deficits in voluntarism and hence in the adequacy of his capacity for informed consent. Here, the assessment of voluntarism was pivotal to the resolution of the case and permitted the patient to assert the self-determination he had always in essence possessed

(20) . In more difficult and less plastic cases, recognition of deficits in voluntarism may not automatically restore this capacity

(21) . Nevertheless, clinicians may feel that aggressively trying to address such deficits is an important component of their professional obligations, including advocating for the patient.

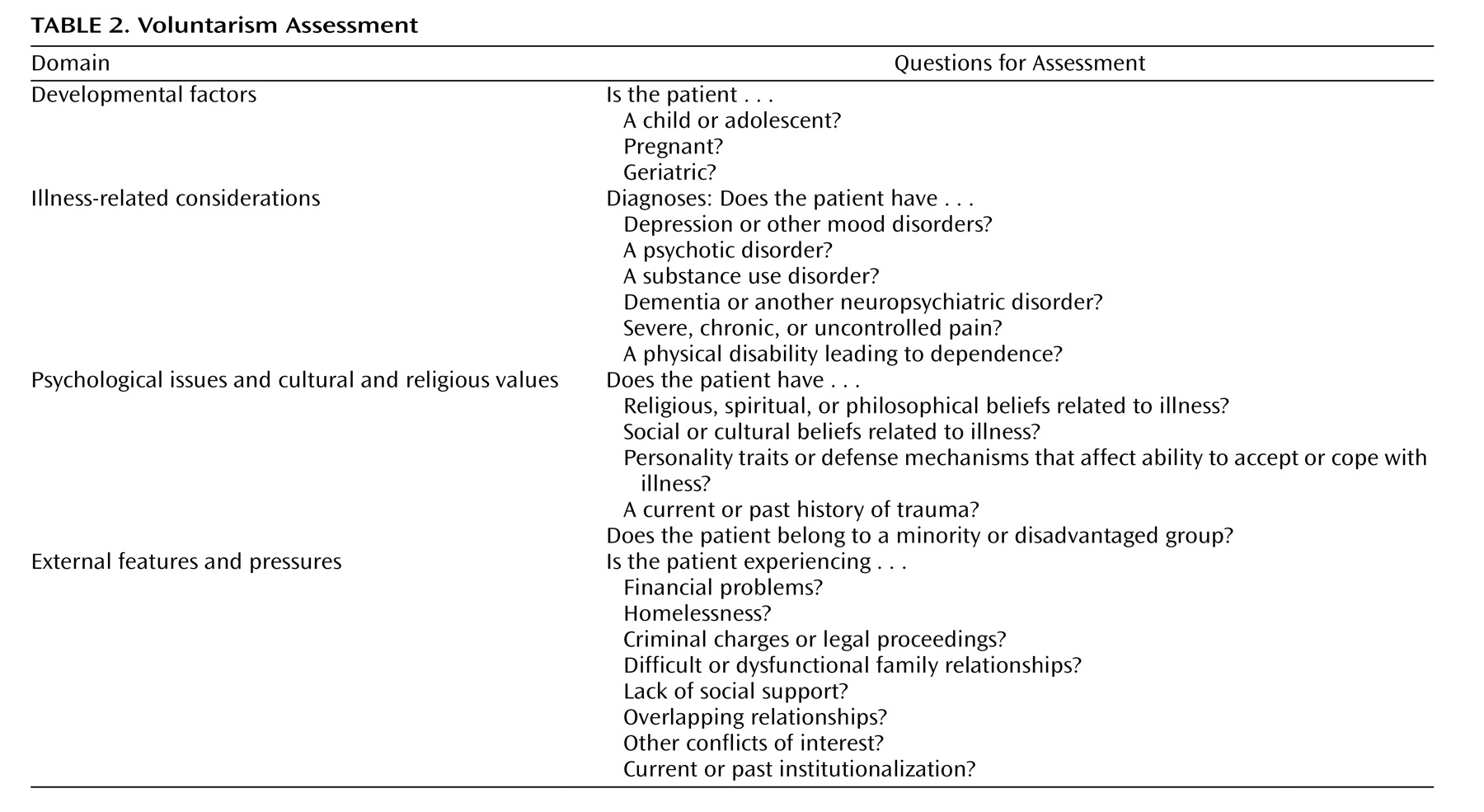

We analyzed this and several other cases to formulate a bedside voluntarism assessment (

Table 2 ). This assessment is purely qualitative, but we hope to use it as the basis for development of a more quantitative assessment. In its current form, the assessment may serve as a consciousness-raising tool and a voluntarism checklist to alert health care practitioners to developmental, illness-related, psychosocial, and external features of clinical treatment that may not be identified or given their proper weight in more traditional informed consent assessments. Applying this bedside voluntarism assessment to the case presented, we find that Mr. B’s capacity for voluntarism was impaired because of the external pressures from his current hospitalization.

The foundation of any informed consent assessment should be a rigorous and methodical medical, neuropsychiatric, and diagnostic evaluation. Cognitively based assessments of decisional capacity are critical, and they will remain the primary means of determining capacity for informed consent. Assessment of voluntarism may be most useful in cases where a comprehensive psychiatric interview and mental status examination do not clearly indicate the presence of psychopathology but clinical intuition, contradictory choices, or existential dissonance hint at some impairment of self-determination that merits further exploration. Just as recruitment of social support or educational interventions can ameliorate or even restore decisional capacity, similar interventions can enhance or restore the capacity for voluntarism. Indeed, the true value of the voluntarism assessment may lie in its ability to unearth these buried features of a clinical picture, thereby allowing apparently insoluble ethical dilemmas to be approached from a different and more fruitful perspective.