Diagnostic Challenges

In summary, Mr. C was an unfortunate middle-aged man with a history of two traumatic brain injuries. He had been suffering from mood and behavior problems since the second incident. In addition, he had encountered several psychosocial stressors, including legal problems, separation from family and religious connections, unemployment, and increasing dependence on family members for assistance. Clearly, the patient’s case was complicated, and many would conclude that his prognosis was poor. Although the formulation of this patient’s case was challenging, successful treatment would emerge from disentangling his symptoms and their respective causes. Hence, we attempted to use an organized approach with four perspectives to define and treat all of the patient’s problems

(5) (See

Figure 1 ).

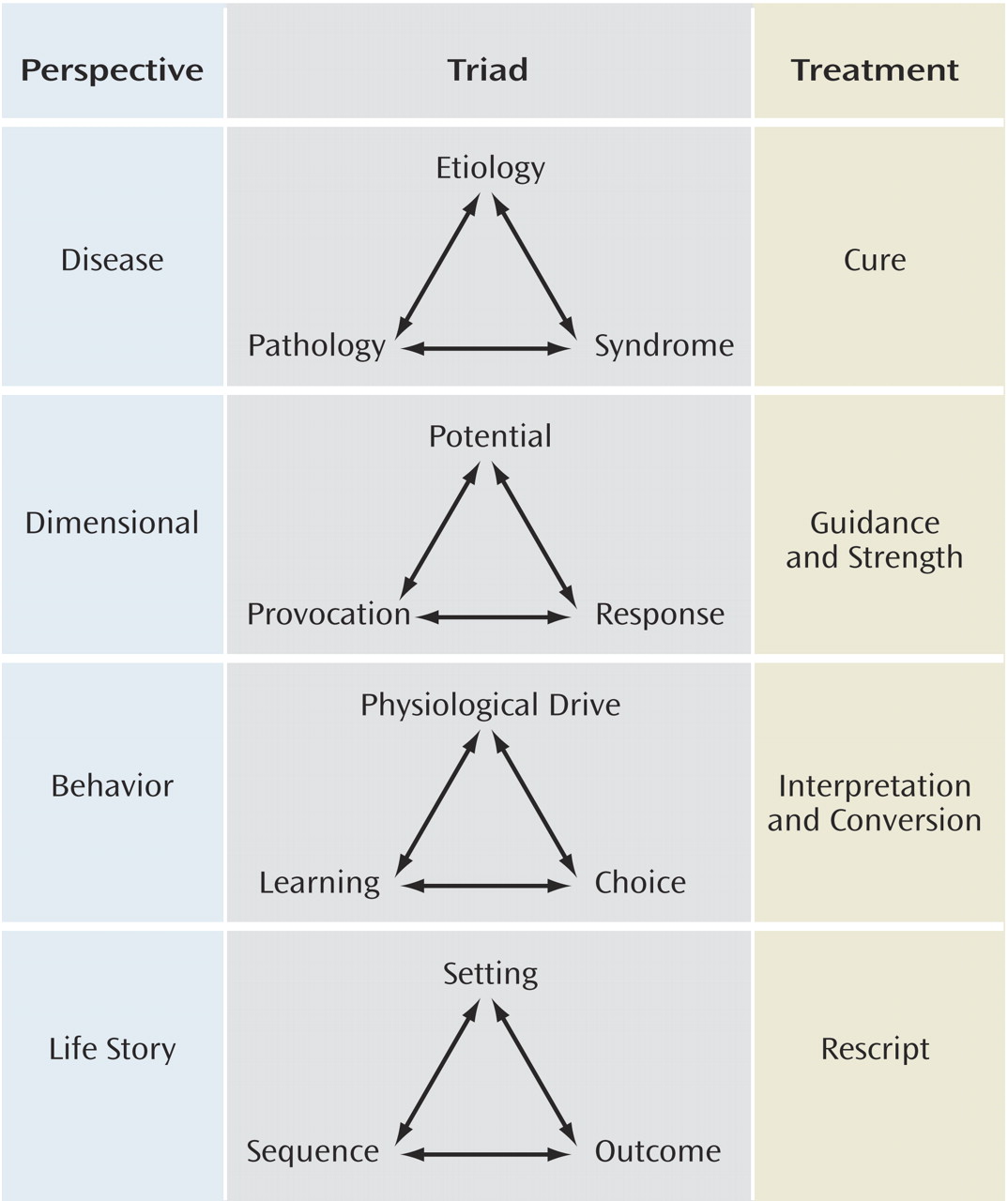

Each perspective has a unique logic and set of principles that direct treatment in a very specific way. The perspective of disease is based on categories and asks, “What does the patient have?” This perspective explains mental disturbances as secondary to a “broken part” in the brain. The perspective of dimensions is based on the logic of gradation and quantification and asks, “What is the patient?” The dimensional perspective explains problems of mental life as arising out of the interaction between a person’s vulnerability (e.g., personality characteristics) and the demands of an environment to which that trait is mismatched or poorly suited. The perspective of behavior is based on the logic of goals and asks, “What is the patient doing?” The behavior perspective emphasizes the goal-directed aspects of behavior and how problem behaviors are gradually shaped by other factors (e.g., internal drives, environmental consequences). The perspective of the life story is based on the logic of narrative and asks, “What has the patient encountered?” The life story perspective highlights how a distressed state of mind could be the understandable result of disturbing life experiences.

Thus, the treatment for each type of problem is also different (see

Figure 1 ): curative in the disease perspective by fixing the broken part, guiding and supportive in the dimensional perspective by strengthening the vulnerability and/or reducing the mismatch between patient traits and environmental demands, interpreting and converting in the behavior perspective by changing goals and reinforcements, and rescripting the patient’s narrative in the life story perspective by offering more encouraging interpretations of unfortunate events.

The Disease Perspective

Several of Mr. C’s symptoms and problems could be explained by the damage caused to his brain. Mood disorders in patients with traumatic brain injury are associated with the disruption of brain circuits involving regions such as the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, basal ganglia, and thalamus

(17) . Studies in depression without traumatic brain injury have also found involvement of the frontal cortical regions and amygdala, suggesting that dysfunction of limbic prefrontal cortical structures impairs the modulation of the amygdala, leading to abnormal processing of emotional stimuli

(18) . Several studies have revealed frontal lobe damage in patients with impulse control problems similar to Mr. C’s, such as improper social etiquette and disinhibition

(19 –

21) .

The treatment approach in the disease perspective focused on curing the disease

(5) . In this case, the injury is irreversible, and it is not possible to cure the disease; however, symptoms of the pathology can be minimized. A literature review revealed that there is a limited evidence base to guide treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms after traumatic brain injury; however, guidelines and reviews based on randomized controlled trials have been published. In particular, the Neurobehavioral Guidelines Working Group has recently done a comprehensive review of the evidence base for these disorders

(22) . Based on this analysis, tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are recommended for depression after traumatic brain injury. There is insufficient evidence to support or refute use of any particular agent for mania or anxiety disorders after traumatic brain injury. For general cognitive functions, there is insufficient evidence to support any agent, but phenytoin in particular may make cognition worse. Agents found to enhance specific types of cognitive functioning include methylphenidate for attention and speed of cognitive processing, donepezil to enhance attention and memory, and bromocriptine for improving executive function. Beta blockers are recommended for aggression. Other treatment options for aggression include methylphenidate, cranial electrical stimulation, SSRIs, valproic acid, lithium, tricyclic antidepressants, and/or buspirone

(22) .

Mr. C’s major depression responded well to sertraline, an SSRI. Other researchers have recommended the use of sertraline for the treatment of major depression after traumatic brain injury

(23 –

25) . Symptoms of dysexecutive function, such as impulsivity and disinhibition, are being controlled by amantadine. There are several anecdotal reports on the use of amantadine, a dopaminergic agonist and an

N -methyl-

d -aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, in patients with dysexecutive function after traumatic brain injury

(26 –

28) .

Thus, many of Mr. C’s problems (major depression, cognitive deficits) could be explained by the disease perspective. However, to formulate all of his problems as purely biological was to preserve the disease at the expense of the person. Also, relying solely on biological treatments to treat the symptoms was insufficient and not holistic. Other researchers also agree that psychiatric disturbances after traumatic brain injury have multiple causes: social, environmental, developmental, and behavioral

(17,

29,

30) . However, an approach for how to deal with these causes is usually not provided. We have attempted to address the emotional and cognitive problems in this patient by applying the four perspectives approach.

The Dimensional Perspective

The central theme of the dimensional perspective is that emotional distress can be secondary to an individual’s cognitive or affective trait vulnerabilities

(5) . Studies have shown that patients with traumatic brain injury often have cognitive deficits and alterations in personality and emotional regulations that can have adverse outcomes

(31) . Common changes include disinhibition, irritability, apathy, agitation, aggression, indifference to surroundings, and problems with executive functioning

(32) . Disinhibition may be a particular problem in this patient population. In a study comparing patients with traumatic brain injury to normal comparison subjects on the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines

(33), which is a measure of borderline traits, the patients with traumatic brain injury had more borderline-like traits than the comparison subjects on tasks of inhibition and object relations. The subjects with traumatic brain injury had a poorer performance on the “go/no go” task, indicating difficulty inhibiting their responses. The dimensional perspective includes assessing potential, provocation, and response. For example, Mr. C’s cognitive inefficiencies, such as inattention and poor memory, coupled with his personality traits after traumatic brain injury of low frustration tolerance and quickness to anger (potential) placed him at risk when stressed or challenged (provocation) to react aggressively or inappropriately (response). Although these cognitive and affective trait vulnerabilities were clearly a sequelae of traumatic brain injury, they were now the patient’s new persona or new baseline. Trauma to the brain often causes injury to the frontal-temporal regions with resultant cognitive, behavioral, and emotional impairments that can persist for decades after traumatic brain injury

(34) . These impairments can be further exaggerated by other factors, such as comorbid psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, and environmental factors, such as excessive stimulation and/or limited psychosocial support

(34) . Because there is no cure for traumatic brain injury, treatment for a dimensional problem should focus on factors precipitating the emotional distress and strategies used to reduce the emotional response. The dimensional approach helps recognize the patient’s vulnerabilities and provides guidance and strength to help the patient function to the fullest potential.

In accordance with the dimensional perspective, Mr. C received guidance through instruction, practice, and support during individual and group therapy sessions. During these sessions, Mr. C was educated about brain injury and its consequences. Guidance included encouraging Mr. C to acknowledge his deficits and to recognize a “new” baseline. During therapy sessions, his strengths (e.g., motivation to get better, desire to be self-sufficient, absence of substance abuse) and weaknesses (cognitive deficits and specific personality traits) were discussed. Modeling and role playing were used to demonstrate how his vulnerabilities could lead to trouble. Discussing his strengths improved his self-esteem and helped him stay motivated. Guidance also included training to improve his interpersonal relationships, with an emphasis on learning to listen, exercising self-control when angry, and making conversation in a polite and responsible manner. Group counseling was useful in providing actual interactions with peers and opportunities for socialization to offset the loneliness that often provoked Mr. C’s distress. This supportive and structured setting gave Mr. C an opportunity to obtain safe feedback from peers. In addition, regular family meetings were held to provide additional instruction and support.

Behavior Perspective

Even though the disease and the dimensional perspectives could explain many of Mr. C’s behavioral problems, some of them, such as the sexually inappropriate behavior, were better explained using the behavior perspective. Sexually inappropriate behavior can be particularly troublesome in this patient population. Simpson et al.

(35) related patients with traumatic brain injury with sexually inappropriate behavior to comparison subjects with traumatic brain injury without the behavior to identify social, cognitive, and medical correlates. They found a higher incidence of psychosocial impairment and failure to return to work after traumatic brain injury in subjects with traumatic brain injury with sexually inappropriate behavior. Premorbid temperament or postinjury medical or cognitive variables were not significantly more common in the traumatic brain injury group with sexually inappropriate behavior. The researchers warn against having “a simplistic explanation,” such as frontal lobe damage or psychosocial disturbance before traumatic brain injury, as the cause for sexually inappropriate behavior that emerges after injury.

The behavior perspective identifies conditions that represent problems of choice and control and is governed by a triad of physiological drive, conditioned learning, and choice. Motivated behaviors, such as eating, drinking, sleeping, and sexuality, all depend on learning and maturation. However, these normal behaviors can become a “disorder” when carried to excess in form or frequency. These abnormal motivated behaviors are often sustained by rewarding consequences. Mr. C’s inappropriate sexual behavior is a typical example of an abnormal goal-directed behavior. Even though injury to the frontal lobes may have resulted in impulsivity and disinhibition, making him vulnerable to hypersexual acts, this behavior is probably shaped and maintained by positive reinforcements that Mr. C receives when he indulges in touching others. The rewards, such as joy and/or attention, that he receives may also be a distorted form of sexual outlet.

Treatment involves stopping or converting the problematic behavior. This approach involves confronting behavior, challenging the patient’s reluctance to change, and adopting the new goal of striving to end it. The behavioral approach has been shown to help in this patient population. Fyffe et al.

(30) described a case of a 9-year-old boy diagnosed with traumatic brain injury who continued to maintain inappropriate sexual behavior secondary to positive reinforcement in the form of social attention. A behavioral intervention in the form of functional communication training and extinction led to a reduction of the inappropriate behavior. Zencius et al.

(36) described the effectiveness of simple strategies such as feedback and “scheduled massage” to decrease hypersexual behavior in brain-injured subjects. Bezeau et al.

(37) reviewed the various types of sexually intrusive behavior following traumatic brain injury and discussed methods for assessment and management.

Evaluation and treatment of inappropriate sexual behavior is often frustrating and challenging for the therapist and awkward, embarrassing, and sometimes even shameful for the patient and/or his family. In the behavioral approach, these behaviors should be addressed respectfully and in a professional manner, and the therapist should be sensitive to the feelings of the person/family

(38) . The person should be told in a clear, straightforward manner that the behavior is unacceptable. Family members should be educated about the frequency of socially and sexually inappropriate behaviors after traumatic brain injury.

Management of Mr. C’s hypersexual behavior included a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. The increased sexual drive was reduced pharmacologically with leuprolide. There is a significant literature on the use of medroxyprogesterone and leuprolide acetate for the treatment of paraphilias and hypersexual behavior in patients with and without traumatic brain injury

(39 –

42) . Psychotherapy included group therapy and individual therapy focused on providing clear recommendations about acceptable and unacceptable behavior. Examples include avoiding people and places where he was likely to be vulnerable to hypersexuality, encouraging him to have a responsible person supervise him when he was meeting with friends, role-playing his actions before his dates, modeling and providing feedback, and encouraging repetition of appropriate behavior. Regular discussion in simple language about the feelings and rights of the person being touched and the legal consequences he had to suffer because of his actions also helped. Mr. C’s strong religious beliefs helped to reduce and keep this behavior in check.

The behavior perspective may also help patients with traumatic brain injury with various other inappropriate behaviors. Hegel and Ferguson

(43) demonstrated a significant reduction in aggressive behavior using the technique of “differential reinforcement of other behaviors” in a brain-injured man. Tiersky et al.

(44) compared the effectiveness of individual cognitive behavior psychotherapy and individual cognitive remediation therapy to regular follow-up treatment in patients with mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. A total of 20 subjects were followed for 11 weeks. They found that the group that received cognitive behavior therapy/cognitive remediation therapy had reduced emotional distress and improved attention at 1 and 3 months posttreatment. Bell et al.

(45) used a novel but simple method of scheduled telephone intervention with counseling and education. In this study, 85 patients with traumatic brain injury were selected at random for telephone intervention, and 86 patients with traumatic brain injury, for usual outpatient care. The telephone interventions consisted of motivational counseling and education and counseling regarding follow-up appointments and medications. At the end of 1 year, those who received telephone intervention fared significantly better on several behavioral outcomes and overall quality of life. Cox et al.

(46) also demonstrated the effectiveness of systematic motivation counseling to treat substance abuse in patients with traumatic brain injury. Those who received systematic motivation counseling had a significant reduction in negative affect and substance abuse compared to patients with traumatic brain injury without systematic motivation counseling. Other types of behavioral interventions found to be helpful for patients with traumatic brain injury include natural setting behavior management, in which the focus is on education and individualized behavior modification in the natural community setting

(47), and multidisciplinary treatment

(48) . The latter study revealed that targeting patients with traumatic brain injury with pre-injury psychiatric problems is effective in reducing depressive symptoms postinjury.

The Life Story Perspective

The transient episodes of sadness and hopelessness that Mr. C experienced are less satisfactorily explained by any of the previous perspectives and are best explained by the life story perspective. This perspective takes into account events that have taken place in a person’s life and tries to explain their distress as an outcome of this narrative

(5) . In other words, the life story perspective attempts to make sense of emotional problems as meaningful responses to life encounters. McHugh and Slavney

(5) defined the life story perspective as the triad of setting, sequence, and outcome. In the case presented, the setting is the brain injury; sequences include the loss of his job, separation from his wife, family conflicts, and legal problems; and outcomes are the demoralized states of sadness, loneliness, helplessness, and rage.

The goal of therapy in the life story perspective is to “rescript” events and the negative meanings adopted by the patient. Individual and group therapy often help the person to “reinterpret” his or her life by providing an understanding of the “setting” and “sequence” and coping skills and compensatory strategies to modify the outcome. Ultimately, the patient is encouraged to continue his or her life with an acceptance of past events and renewed optimism about the potential for future successes that will lead to a satisfying and fulfilling life.

Studies indicate that patients with traumatic brain injury face numerous psychosocial problems, such as those experienced by Mr. C, that contribute to emotional distress, anger, and aggression

(29,

49) . When compared to those with other chronic medical illnesses, people with traumatic brain injury have a unique set of problems that increases the risk for emotional distress. First, traumatic brain injury strikes suddenly, causing a dramatic change in functional, social, and occupational life. Second, because of this acute onset, family members have not made any preparations to take care of the handicapped brain-injured person. This often results in family relationships faltering. Third, because the physical sequelae of traumatic brain injury often resolve or stabilize, the psychiatric disturbances continue to persist or relapse, which many families of patients with traumatic brain injury have difficulty understanding. Fourth, many patients with traumatic brain injury are unable to obtain rehabilitation services that they need because of poor finances, lack of insurance, or difficulty finding an appropriate place. Finally, impaired self-awareness is a common problem in traumatic brain injury

(50) . Patients with traumatic brain injury with impaired self-awareness when compared to those without impaired self-awareness show more psychopathological symptoms, worse neuropsychological function, and decreased functional independence

(51) . Sherer et al.

(52) noted that decreased self-awareness after traumatic brain injury is secondary to multiple disruptions of the integrated, broadly distributed neural network associated with awareness rather than lesions in particular brain regions. Others, however, have noted specific abnormalities in the right anterior prefrontal region in patients with traumatic brain injury with impaired self-awareness in relation to normal comparison subjects

(53) . Lack of insight can be particularly challenging in the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms after traumatic brain injury. Hurt

(54) has proposed three specific strategies to improve self-awareness. They include identification of the strengths and limitations of people with traumatic brain injury by formal vocational testing, confrontation of behavior problems through group therapy, and involvement in a work setting to learn compensatory strategies and rebuild self-esteem. Other methods to improve awareness include education in brain-behavior relations, goal and journal group therapy, and video feedback therapy

(55) .

Mr. C had limited self-awareness, perhaps because of the right frontal injury. Regular education, individual and group therapy, and gentle confrontation of inappropriate behavior all played a role in improving Mr. C’s awareness of his deficits and improvement in behavior.