There are numerous pharmacological and psychological alternatives for the treatment of unipolar major depressive disorder. However, a substantial number of depressed patients (50%–70%) either do not fully respond to acute treatment or relapse within a year

(1 –

4) .

In recognition of the often poor response of depressed patients to monotherapy, the use of combined pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatment, particularly in more severely depressed patients, is common. Nevertheless, relatively few studies have investigated the benefits of adding psychotherapy to medication in depression, and study results are conflicting

(5) . While in unselected outpatient cohorts only small effects of combination treatment relative to pharmacotherapy alone have been reported, combined approaches appear to be more effective for severely or chronically depressed patients

(5 –

9) . In contrast to the findings among studies of unselected depressed outpatients, two studies of depressed inpatients

(10,

11) showed improved efficacy for adding cognitive and behavioral treatments to pharmacotherapy both at posttreatment

(10) and long-term follow-up

(12) . Two German trials on inpatients, however, reported no advantage for combined treatment with medication and cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) versus medication plus supportive therapy

(13) or medication and CBT versus both monotherapies

(14), respectively.

Despite the fact that inpatient treatment is no longer widely used in the United States and in some other countries, it is the standard of care in Germany and many other countries for more severely depressed patients and is therefore still relevant worldwide. Interpersonal psychotherapy has been shown to be effective in the outpatient treatment of mild to more severe depression

(15,

16) . To our knowledge, there are no controlled trials regarding the efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed, hospitalized patients, although several factors make the approach suitable for inpatient treatment (e.g., the medical model, the simple concept, relatively easy to learn for residents).

We examined the hypotheses that depressed inpatients treated for 5 weeks with psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy would have 1) a higher reduction in depressive symptoms and 2) higher response and remission rates compared with patients treated with pharmacotherapy plus clinical management. For the follow-up period, we hypothesized a better symptomatic and psychosocial long-term outcome and lower relapse rates for patients initially treated with psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy.

Method

Patients

All patients between 18 and 65 years of age referred to our department for acute psychiatric hospitalization by primary care physicians or psychiatrists between Nov. 2000 and Aug. 2003 with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder were prescreened during the first 3 days of admission for enrollment in this study.

Indications for inpatient treatment included suicidal risk, inability to function, severe conflicts at home, and nonresponse to outpatient treatment. Of the approximately 300 prescreened patients, about 50% were ineligible, mainly because of diagnostic (e.g., comorbid borderline personality disorder or psychotic symptoms) or medication reasons (e.g., nonresponse to a previous appropriate trial of the study medication or clinical indication of the need for additional medications). Inclusion criteria consisted of a primary diagnosis of major depression (single-episode, recurrent, or bipolar II) according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

(17) (SCID)

(18) and a score of ≥16 on the 17-item version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D)

(19) . Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) concurrent diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, primary substance abuse or dependency, other primary axis I disorders, mental disorder because of organic factors, and borderline or antisocial personality disorder; 2) psychotic symptoms; 3) severe cognitive impairment; 4) contraindications to the study medication; and 5) being actively suicidal. The study was approved by the University of Freiburg Ethical Committee. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

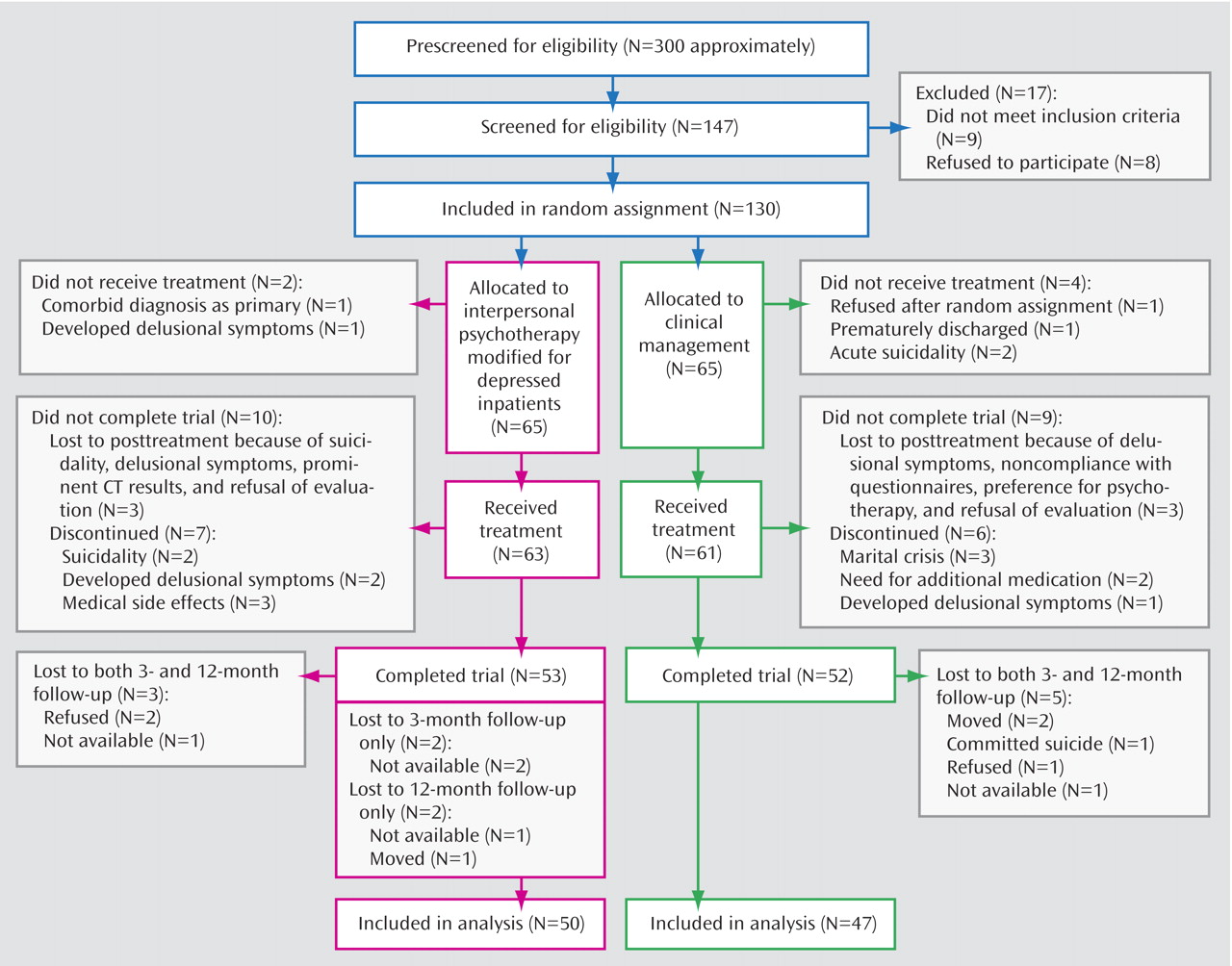

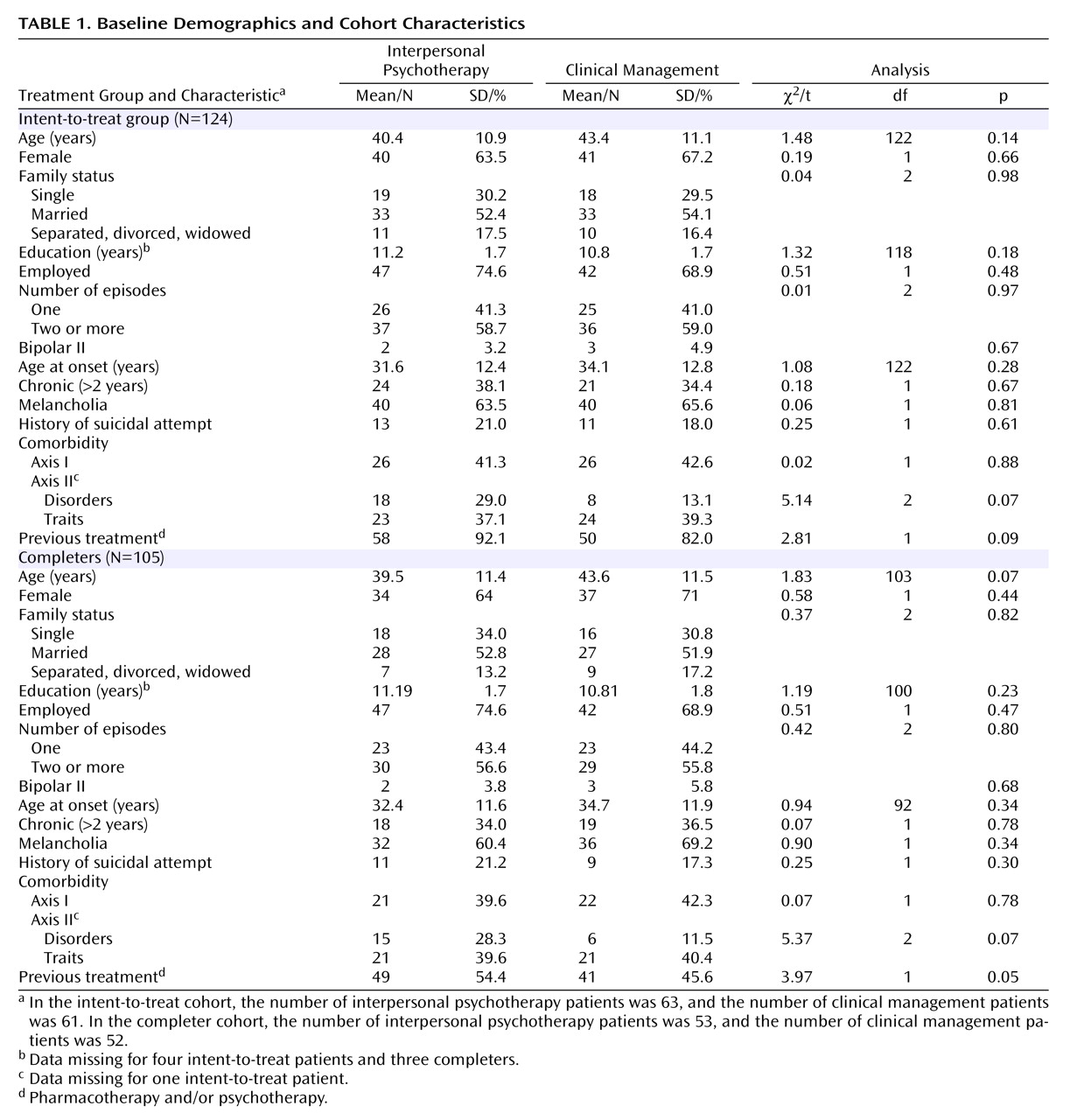

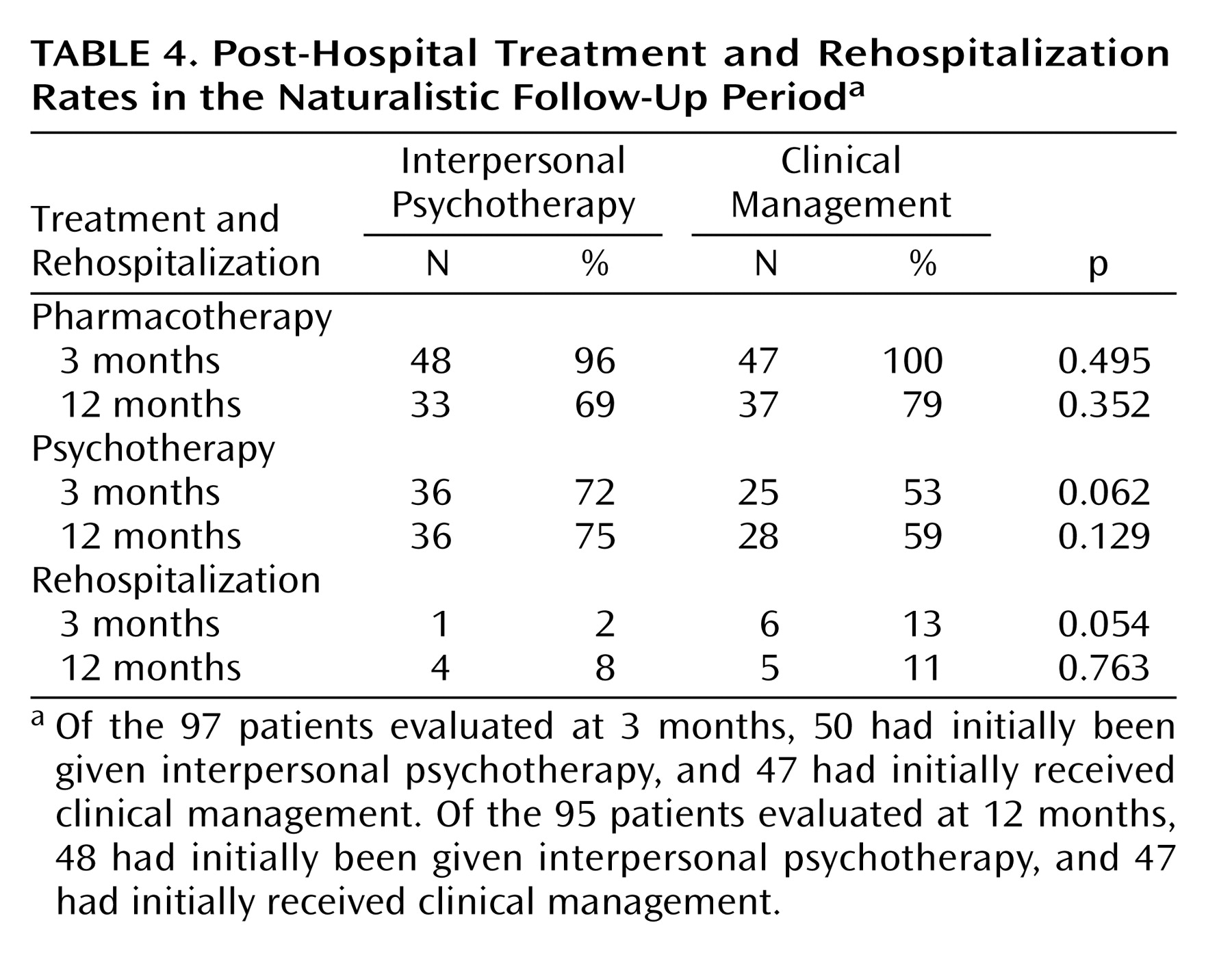

In the intent-to-treat analyses, 124 patients who received allocated intervention were included, and 105 patients completed the program (

Figure 1 ). There were no statistical differences between the dropouts and the completers on any of the demographic or clinical variables. Follow-up analyses were restricted to patients for whom termination data were available (N=97).

Design Overview

Randomization

Patients were randomly assigned by a computer program (dynamic allocation using minimization method) using the following stratification variables: age, gender, unipolar disorder versus bipolar II disorder, comorbidity on axis I, duration of index episode, and number of episodes. These variables were used because they are likely to affect treatment outcome

(20) . The participants’ relevant data were entered into the computer database by the enrolling interviewer, and the allocation sequence was unpredictable for any of the investigators.

Treatment Conditions

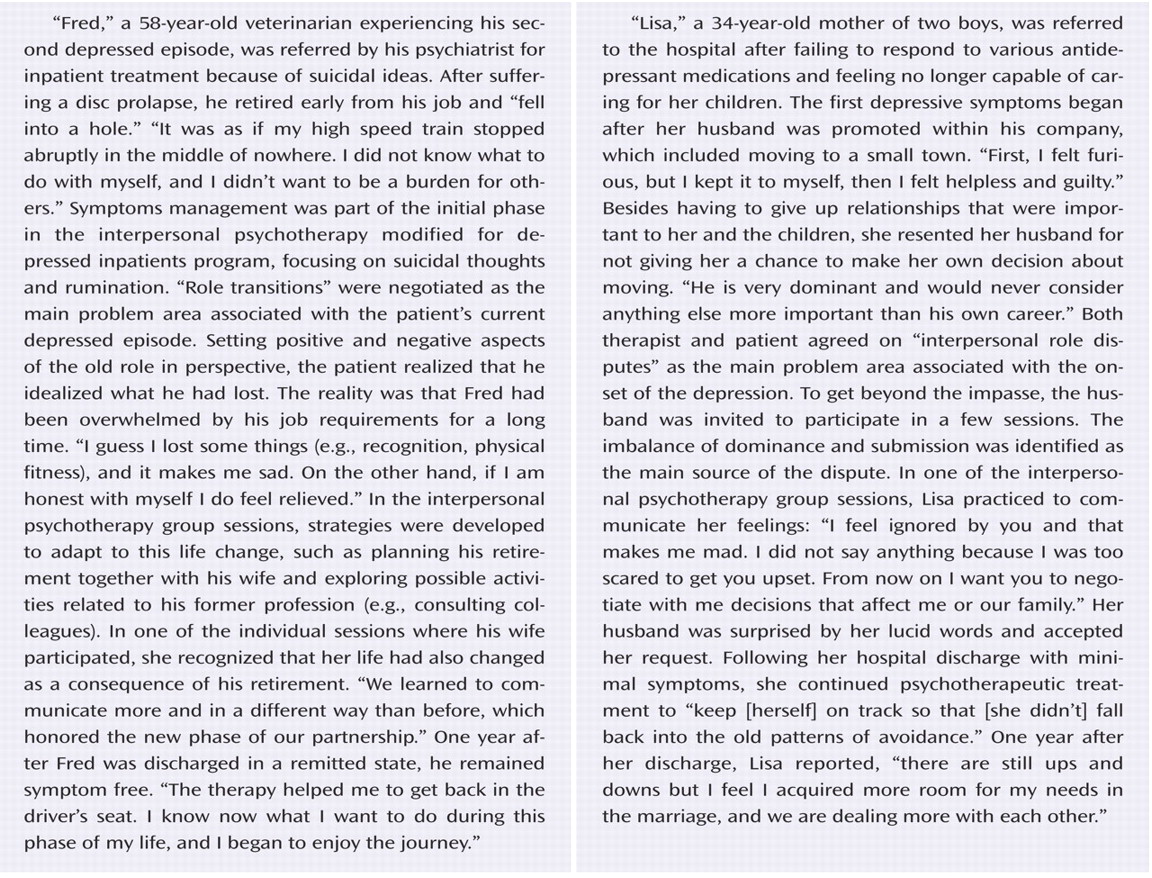

Modifications of interpersonal psychotherapy

(21) for an inpatient setting

(22) included 1) higher frequency of sessions; 2) eight additional interpersonal psychotherapy group sessions; and 3) inclusion of significant others in some of the sessions, mainly for the purpose of education about the disorder. Fifteen individual sessions (all videotaped) of approximately 50 minutes were administered three times weekly over 5 weeks. For the intent-to-treat cohort (N=124), the average number of interpersonal psychotherapy sessions was 12.8 (SD=2.75; range: 4–15). The treatment completers (N=105) had a mean of 13.5 (SD=1.79; range: 8–15) sessions. Four patients were discharged before the end of the program because of recovery and therefore had less than 15 sessions.

All interpersonal psychotherapy therapists (five psychiatric residents and five clinical psychologists) were in an advanced or completed stage of a 3-year psychotherapy training program, had attended training in interpersonal psychotherapy, and had received weekly group supervision. The patients in the clinical management condition also received three weekly sessions according to a brief guideline (adapted from “Guideline for Medication Clinic,” by C.F. Reynolds, III and J.M. Perel). Clinical management was defined as a psychoeducative, supportive, and empathic intervention of 20 to 25 minutes and was delivered by psychiatric residents. All residents (N=26) had a didactic training in clinical management for at least one-half day. Audiotaped clinical management sessions were continually checked for adherence using the Therapist Rating Scale

(23) . Both treatment groups received standardized pharmacotherapy (described in a data supplement that accompanies the online version of this article) in addition to interpersonal psychotherapy or clinical management by the treating physician who was not blind to the patients’ treatment status. The first-line treatment was sertraline (intent-to-treat cohort: N=81; completers: N=68). In case of a known nonresponse to sertraline in a patient’s treatment history, amitriptyline or amitriptyline-N-oxide was applied as the second line treatment (intent-to-treat cohort: N=35; completers: N=30). Eight patients (six clinical management and two interpersonal psychotherapy patients) who started treatment with sertraline received additional amitriptyline or amitriptyline-N-oxide after the second week because of an unsatisfactory response to sertraline. In the intent-to-treat cohort, the mean final dosage for sertraline was 90.2 (SD=43.9) mg/day (range: 50–250 mg/day), and among completers it was 86.03 (SD=41.9) mg/day (range: 50–250 mg/day). For amitriptyline or amitriptyline-N-oxide, the mean final dosage in the intent-to-treat cohort was 175.43 (SD=66.9) mg/day (range: 75–360 mg/day), and among completers it was 182.17 (SD=69.7) mg/day (range: 75–360 mg/day). The number of patients using sertraline or amitriptyline in both treatment conditions was similar (in both the intent-to-treat and completer cohorts). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the mean final dosage between interpersonal psychotherapy and clinical management patients for both types of medication in both cohorts. All patients participated in usual hospital activities such as daily ward rounds, occupational therapy groups, and physiotherapy.

Assessments

The 17-item version of the HAM-D

(19) served as the primary outcome measure. Secondary measures included the Beck Depression Inventory

(24), the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale

(25), and the Social Adjustment Scale Self-Report

(26) . In the follow-up period, weekly psychiatric status ratings, based on DSM-IV symptoms of depression, were recorded retrospectively by the patient. Criteria for the psychiatric status ratings (according to the Longitudinal Interview Follow-up Evaluation

[27] ) format ranged from “1=no symptoms” to “6=meets full criteria of major depression.”

Treatment response was defined a priori as a reduction in symptom severity of 50% or higher on the HAM-D and remission as a score of 7 or less on the HAM-D. Following initial posttreatment response, patients were considered to have relapsed if they had a HAM-D score of ≥15 in combination with a psychiatric status ratings score of ≥5 for a minimum of 2 weeks. Sustained response was defined as responding to acute inpatient treatment and maintaining the response as well as staying free from relapse and not being rehospitalized during the course of follow-up. Sustained remission was defined as a score of 7 or less on the HAM-D plus a psychiatric status ratings score of 1 or 2 for at least 2 weeks following initial remission with no relapse and no rehospitalization during the follow-up period.

The SCID

(18) was conducted by trained and experienced clinical psychologists. The efficacy of treatment was evaluated 5 weeks after the beginning of treatment and 3 and 12 months posthospitalization in terms of a naturalistic follow-up. The evaluations were performed by blind and independent raters (clinical psychologists) who were not involved in the inpatient care and not located in the hospital. The patients were instructed not to mention anything that might reveal their treatment group to the evaluator. Interrater reliability for the HAM-D was obtained from all evaluators rating a random cohort of 13 audio- or videotaped HAM-D interviews (intraclass correlation coefficient: 0.94).

Statistical Methods

Cohort size was based on a power analysis for repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with an alpha set at 0.05 and an assumed moderate effect size (HAM-D: f 2 =0.15). A cohort of 53 participants per treatment would have yielded an estimated power of 95%. The cohort size for a two-group comparison (one sided) should be 51 patients per treatment to detect an effect size of d=0.50 at a power of 80% and alpha <0.05. Demographic and clinical characteristics of treatment groups were compared using chi square or Fisher’s exact tests and unpaired t tests.

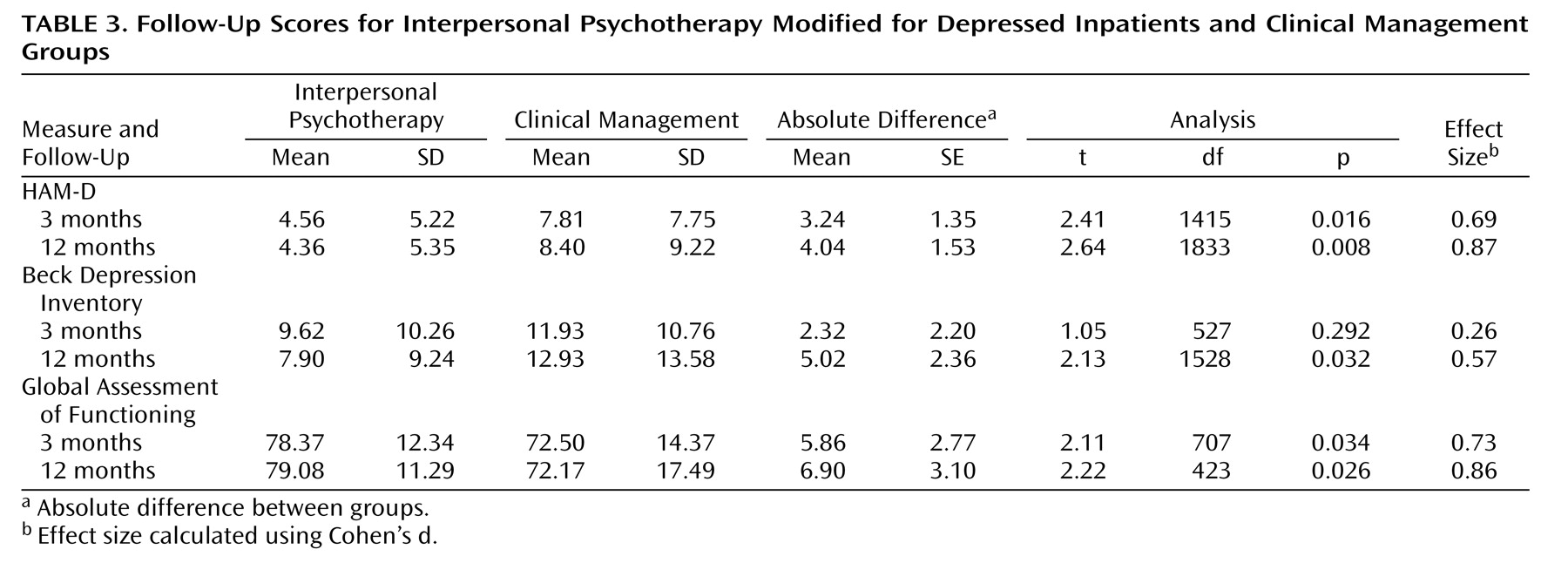

Posttreatment analysis : Analyses for both the intent-to-treat and the completer cohorts are reported. Overall efficacy of treatment was assessed by conducting analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) controlling for pretreatment scores on all outcome measures by treatment condition at termination. The effects of time were analyzed in a repeated-measures ANOVA. When attrition occurred between baseline and posttreatment, “last observation carried forward” was used.

Follow-up analysis : Completer analyses of the HAM-D and the Beck Depression Inventory at 3 and 12 months were conducted to examine differences between the treatment groups. For the follow-up analysis, we adopted a multiple imputation approach

(28 –

30) . Response, remission, and relapse data for the percentage of patients who reached cutoff scores were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Treatment effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d statistic

(31) and for categorical measures using procedures described by Rosenthal

(32) for better comparability with previous studies. All statistical tests were conducted using a two-tailed alpha level of 0.05.

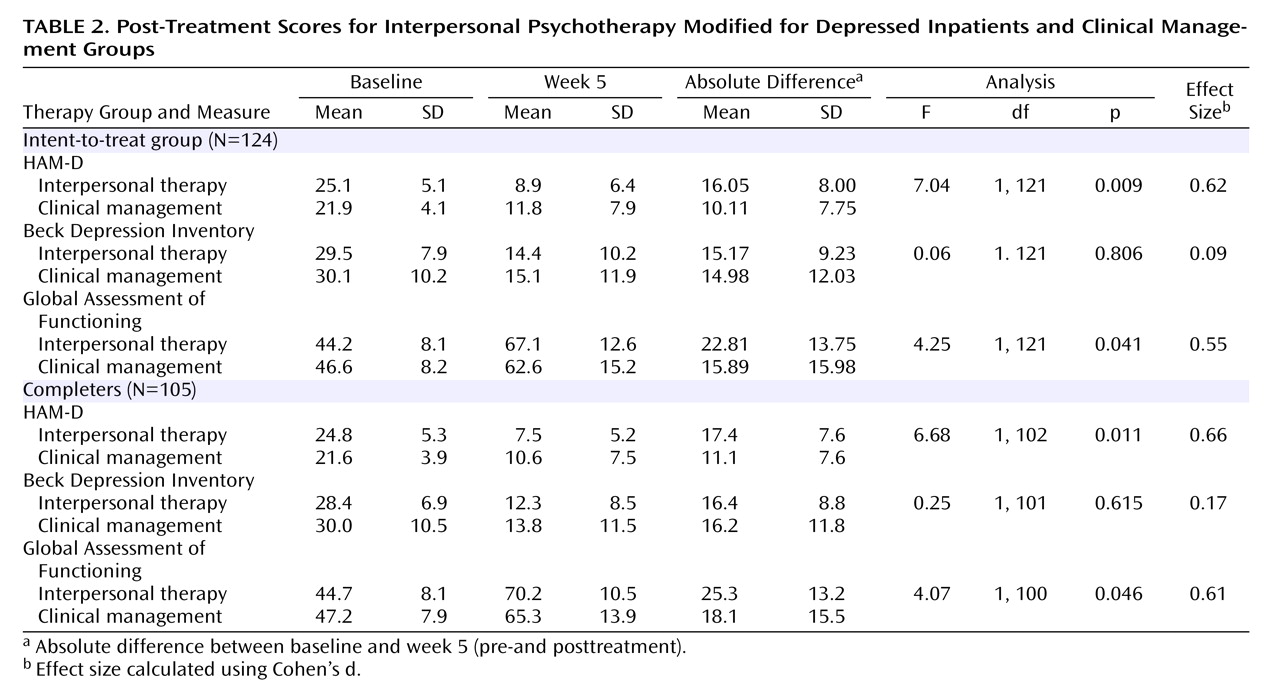

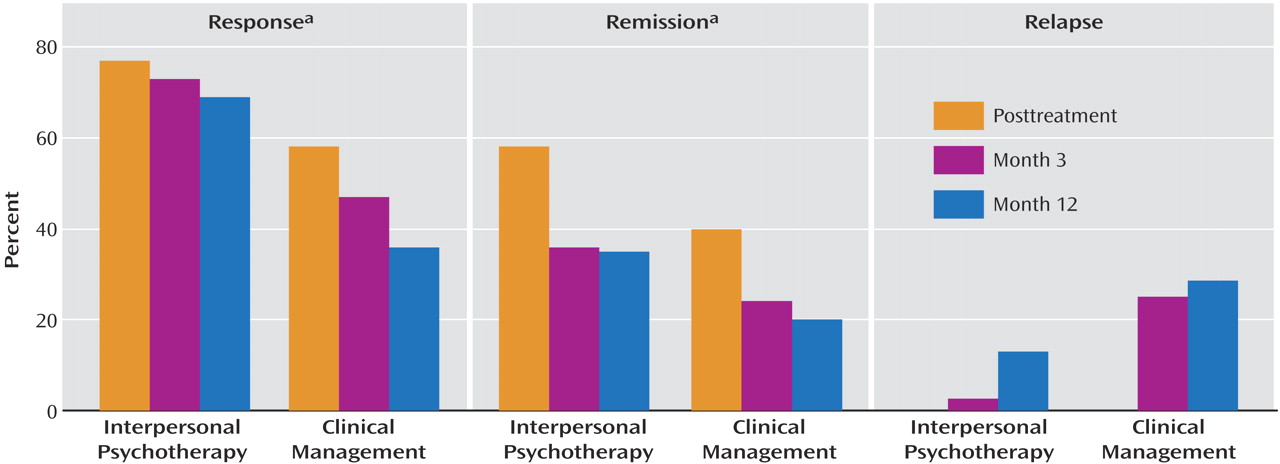

Discussion

Given the short time period of acute treatment in our study and a strong comparison condition, the short- and long-term advantage of adding psychotherapeutic intervention to pharmacotherapy is impressive. The high response (70%) and remission rates (49%) and the low relapse rates (13% in a 12-month period) may reflect the high intensity of the multicomponent treatment program with 15 individual and eight additional group sessions. The intensive delivery of therapy in the acute phase possibly conveys a unique treatment advantage for more severely depressed patients. However, the brevity of the intervention may have imposed a ceiling on the maximum efficacy of the treatment. Miller et al.

(35) concluded that current treatments are not very efficacious in the aftercare of recently discharged major depressive disorder patients. They suggest that beginning psychotherapy while in the hospital may be more advantageous than delaying initiation until discharge. In fact, the timing of additional psychotherapy initiation seems to play an important role. Frank et al.

(36) also suggest not waiting for the period of disorder stabilization to add psychotherapy. Our data clearly support this view. Compared with previous studies with depressed inpatients

(10 –

14), this study differed in having utilized a larger cohort size, a more comprehensive treatment program, and a different psychotherapy method that may have affected treatment response more favorably.

Several factors may account for the discrepancy between clinician and patient ratings. First, the two measures show divergent factor structures

(37) . Furthermore, Lambert et al.

(38) demonstrated larger effect sizes and a higher sensitivity for the HAM-D compared with the Beck Depression Inventory. An additional possibility addresses the familiar phenomenon that more severely depressed patients require a longer course of treatment to recognize their progress because of a negative thinking bias

(39) .

This study has several limitations. First, the entire cohort was heterogeneous in terms of subgroups of depression being chronic, recurrent, or comorbid. In terms of generalizability and external validity, however, this could be considered a strength of the study, since the population of depressed, hospitalized patients is usually comorbid, more severely impaired, and disturbed in a complex way. Second, the terminology of remission was inconsistent with other work

(40), but this was because of the short treatment period defined on the basis of a single assessment covering only 1 week. In the follow-up phase, there were only two assessment points using the HAM-D. On the other hand, weekly psychiatric status ratings were recorded by the patient to identify change over time in depressive symptoms. Third, since both treatment groups did not receive comparable amounts of therapeutic attention, it is unclear whether the effect is attributable to interpersonal psychotherapy modified for depressed inpatients

per se as opposed to extra time with a therapist. Nevertheless, we find the amount of time spent with a health professional as a main efficacy factor unlikely, since both treatment groups reached ceiling effects in terms of the amount of therapeutic contact because of the inpatient setting.

Finally, these findings were obtained for inpatient treatment and may not be directly transferable to other medical systems in other countries. However, the current cohort appears to be comparable with those seen in acute psychiatric outpatient settings in the United States.

In summary, our results, although having some limitations, support a growing body of evidence

(4 –

6,

8) suggesting that while for the average patient the additional benefits of combined treatment with interpersonal psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy may be limited, this combination treatment offers a strong advantage for more severe and complex patients. Our data suggest that treating depression aggressively during the acute phase of treatment is recommended.

Future studies should examine whether it is more beneficial to add psychotherapy while in the hospital rather than beginning combination interpersonal psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy treatment after hospital discharge. It remains uncertain whether an equally frequent level of treatment provision on an outpatient basis could be similarly effective.