To The Editor: Lithium carbonate is a mainstay in the treatment of mania and bipolar disorder. A serum level between 0.8 mEq/l and 1.2 mEq/l is considered therapeutic, usually obtained with a dose of approximately 900 to 1200 mg/day

(1) . The drug has a narrow therapeutic index, with progressive toxicity ranging from gastrointestinal complaints to marked neurological impairment that correlate with increasing serum levels beginning at about 1.5 mEq/l

(2) .

Electrocardiogram (ECG) manifestations, including prolonged QT interval, T wave flattening and inversion, and first-degree atrioventricular (AV) conduction delay, have been reported with lithium toxicity

(3 –

6) . In rare cases, ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation resulting in death have been reported

(4) .

Sinoatrial block associated with lithium therapy was first reported in 1975

(7) . Subsequent reports cite reversible sinus node suppression as a consequence of chronic lithium therapy, even at therapeutic levels

(8 –

10) . Although the mechanism is poorly understood, it may be related to lithium’s competitive inhibition of calcium in the Na

+ /Ca

++ exchange in cardiac cells

(11) .

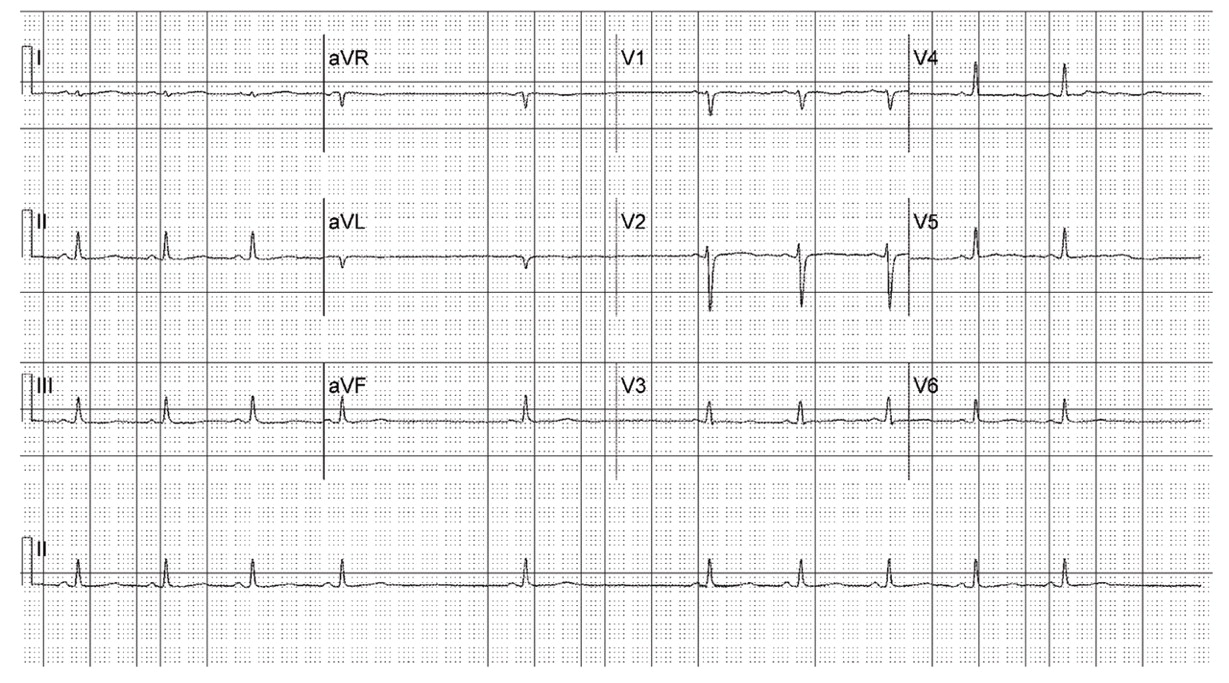

The case report presented here demonstrates prominent bradycardia due to second-degree, type II sinoatrial block that resulted from toxic lithium levels.

In the case described, second-degree (type II) sinoatrial block was present. The prolonged P-P interval was a direct multiple of the shorter P-P cycles. This is in contrast to second-degree type I sinoatrial block (Wenckebach type), characterized by a sinus pause after progressively decreasing P-P intervals. In such instances, the sinus pause duration is less than two P-P cycles.

The patient’s ECGs also demonstrated 4:3, 5:4, and 6:5 second-degree type I sinoatrial Wenckebach block during dialysis (tracings not shown).

After dialysis, the patient’s lithium level decreased to 0.41 mEq/l. There was no further evidence of sinoatrial block. In this case, renal insufficiency, likely secondary to dehydration in combination with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory therapy, may have precipitated elevated serum levels of lithium, despite the patient’s initially low dose. In the setting of dehydration and vomiting, the lithium ion is selectively resorbed in the renal tubules, sometimes accumulating to toxic levels. Indeed, the triad of hypokalemia, hypochloremia, and metabolic alkalosis observed on admission was consistent with a history of bulimia nervosa, revealed later in the patient’s hospitalization. Of note, chronic lithium therapy, by itself, may result in renal insufficiency and other renal toxicity

(12) .

As the uses of lithium continue to expand with an increasingly larger patient population, clinicians must be mindful of the cardiac risks associated with lithium therapy, including sinoatrial block with resultant bradycardia, which can occur abruptly with chronic therapy.