Diagnosing Adolescent Substance Use and Co‐Occurring Disorders Using the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs Quick Version‐4

Abstract

Objective

Methods

Results

Conclusions

Trial registration

HIGHLIGHTS

METHODS

Participants & Procedures

Measures

Data Analysis

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

| Characteristics | Adolescents (12–17) | Adults (18 +) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 101,897 | N = 204,711 | ||

| Age‐ mean (SD) | 15.6 (1.25) | 34.2 (11.67) | n/a |

| Male (%) | 71.5% | 61.7% | 1.56 (1.53–1.58) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non‐Hispanic African American (%) | 24.0% | 16.5% | 1.6 (1.58–1.63) |

| Non‐Hispanic Caucasian (%) | 47.8% | 65.7% | 0.48 (0.47–0.49) |

| Hispanic (%) | 26.7% | 14.7% | 2.12 (2.08–2.16) |

| Mixed/other (%) | 13.1% | 7.3% | 1.91 (1.86–1.95) |

| Assessment setting | |||

| Legal system | 9.3% | 15.8% | 0.55 (0.54–0.56) |

| Treatment | 53.7% | 70.8% | 0.48 (0.47–0.49) |

| Home/office | 19.1% | 3.0% | 7.7 (7.47–7.93) |

| Other | 10.5% | 3.9% | 2.87 (2.79–2.96) |

| Unknown | 7.3% | 6.5% | 1.13 (1.1–1.17) |

| Past 90‐day use of alcohol (%) | 50.3% | 49.3% | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) |

| Past 90‐day use of cannabis (%) | 73.5% | 35.0% | 5.14 (5.05–5.23) |

| Past 90‐day use of stimulants (%) | 12.4% | 30.7% | 0.32 (0.31–0.33) |

| Past 90‐day use of opioids (%) | 10.1% | 25.4% | 0.33 (0.32–0.34) |

| Past 90‐day use of other (%) | 16.7% | 14.2% | 1.21 (1.18–1.23) |

| Any past year needle use (%) | 1.7% | 20.5% | 0.07 (0.06–0.07) |

| Current involvement in legal system (%) | 67.8% | 67.9% | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) |

| Any prior diagnoses (%) | 37.3% | 51.3% | 0.57 (0.56–0.58) |

| Alcohol or drug use disorders (%) | 2.7% | 10.2% | 0.24 (0.23–0.25) |

| Attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (%) | 21.5% | 13.8% | 1.71 (1.67–1.74) |

| Antisocial personality disorder (%) | 0.2% | 1.2% | 0.18 (0.16–0.21) |

| Anxiety or phobia disorder (%) | 6.8% | 20.6% | 0.28 (0.27–0.29) |

| Borderline personality disorder (%) | 0.5% | 2.5% | 0.18 (0.16–0.2) |

| Conduct disorder (%) | 1.0% | 0.6% | 1.74 (1.59–1.91) |

| Major depression disorder (%) | 6.4% | 16.0% | 0.36 (0.35–0.37) |

| Other depression, bipolar or mood disorder (%) | 12.1% | 24.7% | 0.42 (0.41–0.43) |

| Intellectual disabilities (%) | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.5 (0.42–0.59) |

| Oppositional defiant disorder (%) | 2.1% | 0.6% | 3.83 (3.56–4.13) |

| Pathological gambling (%) | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.24 (0.12–0.46) |

| Post or acute traumatic stress disorder (%) | 2.6% | 9.5% | 0.25 (0.24–0.26) |

| Somatoform, pain, sleep, eating or body disorder (%) | 0.7% | 1.1% | 0.65 (0.59–0.71) |

| Other cognitive disorder (%) | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.34 (0.24–0.48) |

| Other mental breakdown, nerves, or stress (%) | 0.2% | 0.7% | 0.28 (0.24–0.33) |

| Other personality disorder (%) | 0.5% | 2.4% | 0.22 (0.2–0.25) |

| Other schizophrenia or psychotic disorder (%) | 0.4% | 3.6% | 0.12 (0.11–0.13) |

| Other (%) | 2.1% | 2.3% | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) |

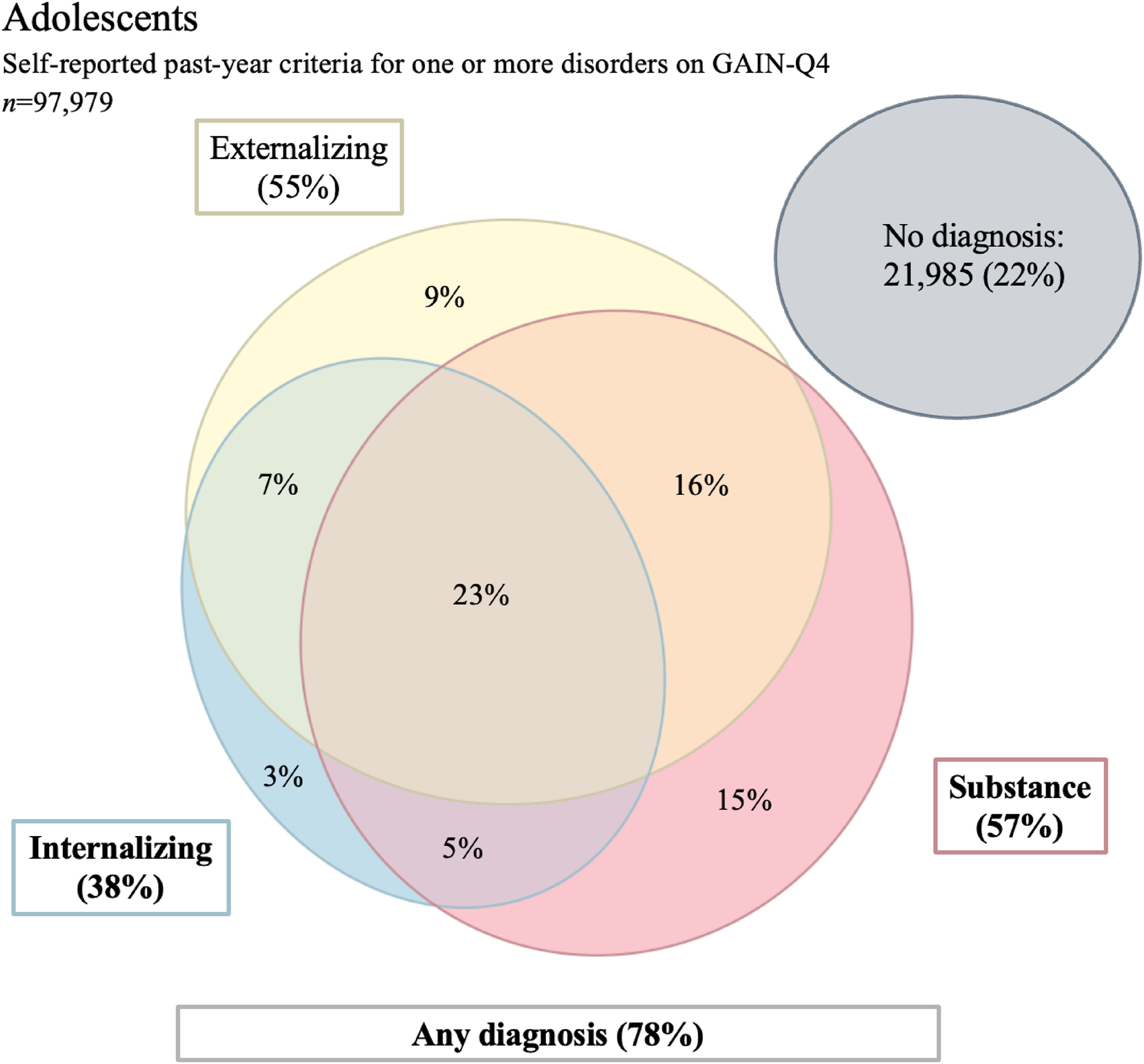

Prevalence

| Past year mental health diagnosis | Prevalence GAIN Q‐4 | Prevalence GAIN‐I | N of yes | Kappa | Sensitivity | Specificity | Percent agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substance use disorder probable diagnosis | 58% | 61% | 57,945 | 0.80 | 89% | 93% | 90% |

| Cannabis | 54% | 50% | 53,887 | 0.71 | 91% | 80% | 85% |

| Alcohol | 46% | 17% | 45,984 | 0.33 | 92% | 63% | 68% |

| Stimulant | 17% | 7% | 16,768 | 0.48 | 93% | 89% | 89% |

| Opioid | 15% | 4% | 15,126 | 0.34 | 97% | 88% | 88% |

| Other drug | 22% | 5% | 22,146 | 0.31 | 95% | 82% | 82% |

| Internalizing mental health probable diagnosis | 38% | 37% | 37,853 | 0.74 | 85% | 89% | 88% |

| Mood | 27% | 30% | 26,789 | 0.68 | 73% | 93% | 87% |

| Anxiety | 26% | 10% | 26,235 | 0.50 | 99% | 83% | 85% |

| Trauma | 25% | 22% | 24,926 | 0.76 | 85% | 93% | 91% |

| Suicide | 11% | 12% | 11,285 | 0.97 | 95% | 100% | 99% |

| Possible psychosis | 7% | 7% | 6640 | 1.00 | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Externalizing mental health probable diagnosis | 55% | 51% | 54,388 | 0.72 | 90% | 82% | 86% |

| Conduct | 45% | 42% | 45,119 | 0.68 | 85% | 84% | 84% |

| ADHD (Attention‐ deficit/hyperacticity disorder) | 52% | 32% | 51,781 | 0.59 | 96% | 72% | 80% |

| Gambling | 1% | 1% | 1160 | 0.41 | 73% | 99% | 99% |

| 3+ of above problems | 69% | 53% | 70,560 | 0.59 | 97% | 62% | 80% |

Sensitivity and Specificity

Agreement

DISCUSSION

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

- Download

- 18.12 KB

REFERENCES

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).