Depressive disorders are the second most common mental illness in the world after anxiety disorders (

1). According to the World Health Organization, the global prevalence of depression in adults is around 5% (

2) although the lifetime risk of experiencing a major depressive episode is much higher and estimated to be 30.1% for women and 17.4% for men (

3). Depression can affect people at any age, but first onset usually occurs in early adulthood (

4). The course of depression is often recurrent with multiple episodes or even chronic. The recurrence of depression 15 years after experiencing a first episode is around 85% in specialized mental health care settings and 35% in the general population (

5). Furthermore, studies show fluctuations in the severity of depression over time, and with the affected persons moving in and out of different depression subtypes (

6,

7). So far, trajectories of depressive symptoms have mostly been investigated in clinical settings or specific (sub‐) populations. However, many people experiencing depression do not seek care and are not visible in clinical settings (

8). The course of depression is influenced by several biological, genetic, and environmental risk factors (

4,

5). The risk factors for recurrence often differ from those for the initial onset. Socio‐demographic factors such as female gender, younger age, and low socio‐economic status, which are risk factors for the onset of depression, do not seem to be risk factors for recurrence; instead, the number of previous episodes and subclinical residual symptoms have been identified as important predictors for recurrence (

5).

Social support refers to the supportive behavior of family, friends, and colleagues and is associated with depression both by quantity and quality (

9,

10). It is also described as a resilience factor with protective properties (

11) and has been shown to play an important role in recovery from depression (

12). A lack of social support can also be a consequence of depression because people with depressive symptoms often withdraw themselves from social situations (

13) and receiving treatment can significantly increase perceived social support (

14). Changes in social support over the life course due to for example, living conditions or socioeconomic status (

15) have so far mostly been investigated in elderly people or dementia patients (

16,

17). Although social support is associated with the onset of depression, evidence is still inconclusive if a lack of social support is also associated with the course of depression (

5,

18).

To improve the effectiveness of mental health care, understanding long‐term trajectories of depressive symptoms and their dynamic interplay with social support is important because individuals with different trajectories might need different interventions.

In this study, we aimed to determine the trajectories of depressive symptoms and social support over 23 years as well as their interrelationship.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

The study is based on the PART (acronym in Swedish: Psykisk hälsa, Arbete och RelaTioner) study, which is a population‐based cohort study of mental health, work, and relations among adults residing in Stockholm County, Sweden. The sample population included 19,742 Swedish citizens aged 20–64 who were randomly selected from the population register of Stockholm County. The baseline measurement was conducted in 1998–2000 (

n = 10,441, response rate 54%). The first follow‐up was in 2001–2003 (

n = 8613, 84%), the second follow‐up was in 2010 (

n = 5621, 66%), and the third follow‐up was in 2021 (

n = 6677, 66%). Participants with at least three measurements of depressive symptoms and social support were included in the analysis. Excluded participants (

n = 3654) were due to (a) being lost to follow‐up; (b) not participating in at least three of the four waves; (c) having partially missing data on depressive symptoms or social support. Thus, the number of included participants was 6787 participants in total (Supporting Information

S1: Supplement A). The Swedish Ethical Review Authority approved the study (Dnr: 96‐260, 01‐218, 03‐302, 2009/880‐31, 2012/808‐32, 2021‐00843, 2021‐024, 2022‐04234‐01). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before study enrollment.

Data Collection and Variables

Data was collected by postal questionnaires at each wave (in wave 4 additionally with web‐based questionnaires) with linkage to the Swedish Longitudinal Integrated Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies (LISA) (

19).

Depressive Symptoms

Self‐reported depressive symptoms within the last 2 weeks were assessed using the Major Depression Inventory (MDI) (

20). The MDI includes 10 items that are scored on a 6‐point Likert scale ranging from 0 (at no time) to 5 (all the time). The item scores are summed up to a total score ranging from 0 to 50 and can be interpreted as “no depression” (0–19 points), “mild depression” (20–24 points), “moderate depression” (25–29 points), and “severe depression” (≥30 points) (

21). However, for prevalence estimates and comparison of characteristics, we used a simplified distinction into “no depression” (0–19 points) and “depression” (≥20 points).

Social Support

Social support was investigated with a Swedish short version of the validated Interview Schedule for Social Interaction (ISSI) that includes two scales. Availability of Attachment (AVAT) was assessed with 5 questions to measure the quality of social support. Availability of Social Integration (AVSI) was assessed with four questions and measures the quantity of social support (

22,

23). The subscale for AVSI and AVAT can be summed into a total ISSI score that ranges from 9 to 44, with higher scores indicating greater availability of social support. For stratification purposes, the scores were recoded according to the interquartile range into “low availability” (<32 points), “moderate availability” (32–39 points), and “high availability” (40+ points).

Covariates

Demographic factors including age and sex were based on information from the LISA register. Anxious distress was assessed using a revised version of the Sheehan Patient‐Rated (Panic) Anxiety Scale (

24) based on the five symptoms: feeling keyed up or tense, feeling unusually restless, difficulty concentrating because of worry, fear that something awful may happen, and feeling that the individual might lose control of himself or herself. The severity of anxious distress was classified as mild (two symptoms), moderate (three symptoms), and moderate‐severe (four or five symptoms). Socioeconomic position (SEP) was recorded using the socioeconomic division (

25) and was categorized into “High/intermediate level salaried employees,” “Assistant non‐manual employees,” “Skilled workers,” “Unskilled/semi‐skilled workers,” “Self‐employed,” and “Student/Retired.” Furthermore, living status, and childhood adversities experienced before the age of 18 (e.g., divorce or death of parents and financial problems) were assessed, as well as the occurrence of 28 different types of stressful life events during the past 12 months (e.g., severe illness and/or death of a spouse or child, loss of employment) (Supporting Information

S1: Supplement B). Participants self‐assessed their health status and reported current treatment for one or more of 24 common somatic disorders (e.g., heart diseases, neurological diseases) (Supporting Information

S1: Supplement C), and whether they previously or currently received treatment for any mental health problem and currently received treatment with psychotropic medication.

Statistical Analysis

Group‐based dual trajectory modeling was used to determine the trajectories of depressive symptoms and social support, as well as the interrelationship between the two. First, single trajectory models were fitted for depressive symptoms and social support separately based on the MDI score and ISSI score. For each model, three possible polynomial specifications (linear, quadratic, and cubic) were considered to describe the trajectories. Different trajectory groups were assigned based on the probability of group membership. The final model was chosen based on the Bayesian information criterion and posterior class membership (greater or equal to 0.7 for each subgroup). Second, the results from the single trajectory models were merged to create the joint trajectory model to determine the conditional and joint probabilities of group membership between the two outcomes.

The association between trajectories of depressive symptoms and social support was assessed with a multinomial logistic regression model by complete case analysis including 6208 participants without missing values in the covariates. Covariates that were identified as potential confounders a priori based on the literature were included in the initial model and the best model was identified using backward selection, the Akaike information criterion, and the loglikelihood ratio test. The significance level was set to α = 0.05 (two‐sided). Interactions between sex and social support and age and social support were investigated.

The group‐based dual trajectory analysis was performed in SAS 9.4 using the procedure PROC TRAJ and the regression analysis was done in R version 4.2.1. with the package “nnet” version 7.3‐17.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Participants included in the analyses differed significantly in their baseline characteristics from those who were excluded. Participants were 58.0% (3937/6787) females and on average 42 years old at baseline. They were older, more likely to be women, have a higher SEP, and live with a partner (and one or more children). Participants had experienced fewer childhood adversities and fewer stressful life events, and they reported a higher availability of social support at baseline. Moreover, participants were less likely to be currently or previously treated for mental illness, less likely to show symptoms of anxious distress, and had a better health status and fewer comorbidities. The prevalence of depressive symptoms according to the MDI at baseline was significantly lower among participants than among those who were excluded (8.6% vs. 13.2%) (Supporting Information

S1: Supplement D).

The prevalence of depression in participants according to the MDI score ranged from 6.8% in wave 3 to 9.7% in wave 4, and the prevalence of depression was higher in women than in men in every study wave (Supporting Information

S1: Supplement E).

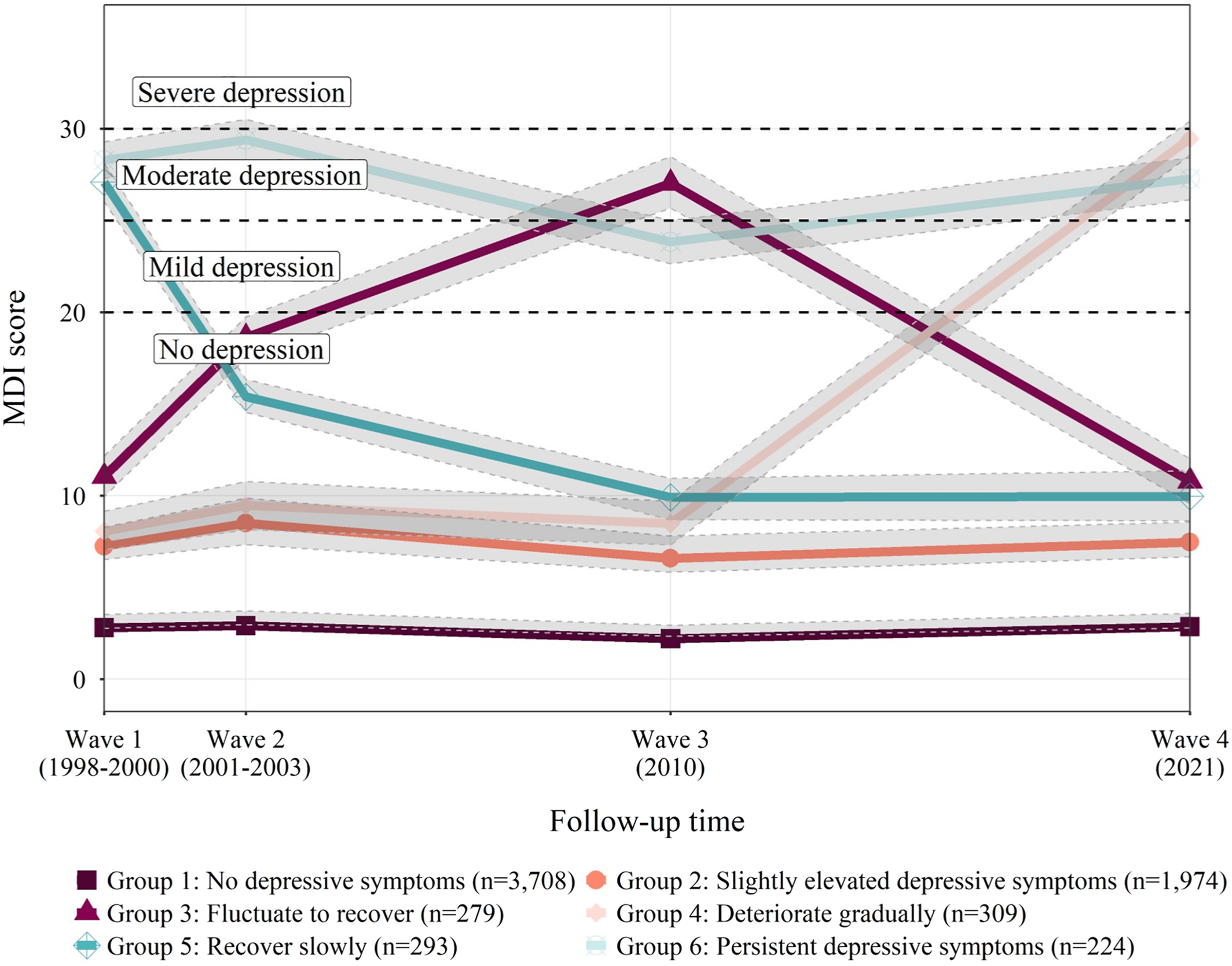

Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms

Six trajectories were selected as the final model for depressive symptoms due to best model fit (Supporting Information

S1: Supplement F). The six trajectories of depressive symptoms identified were: no depressive symptoms (54.6%,

n = 3708), slightly elevated depressive symptoms (29.1%,

n = 1974), fluctuate to recover (4.1%,

n = 279), deteriorate gradually (4.6%,

n = 309), recover slowly (4.3%,

n = 293), and persistent depressive symptoms (3.3%,

n = 224) (

Figure 1).

The characteristics of participants differed significantly among the trajectory groups. More than 75% of those with “persistent depressive symptoms” were women. Furthermore, 4.3% of all women had “persistent depressive symptoms,” whereas only 1.9% of men did. Individuals with “no depressive symptoms” were older than all other groups. Those with “persistent depressive symptoms” had the lowest percentage of high/intermediate level salaried employees (33.2%) and the highest percentage of unskilled/semi‐skilled workers (27.3%). People in the “recover slowly” group had the highest percentage of people living alone (32.0%). The prevalence of low availability of social support at baseline was the highest in those with “persistent depressive symptoms” (58.7%). Childhood adversities and stressful life events in the last 12 months were the least common in those with “no depressive symptoms,” and most common in those with “persistent depressive symptoms.” The “persistent depressive symptoms” trajectory group had the highest prevalence of previous treatment (22.8%), current treatment (22.3%), and current psychotropic medication use (20.5%). Those in the group “recover slowly” were most likely to report symptoms of anxious distress. Participants with “persistent depressive symptoms” reported the worst health status and most frequently reported two or more comorbidities (34.4%) (Supporting Information

S1: Supplement G).

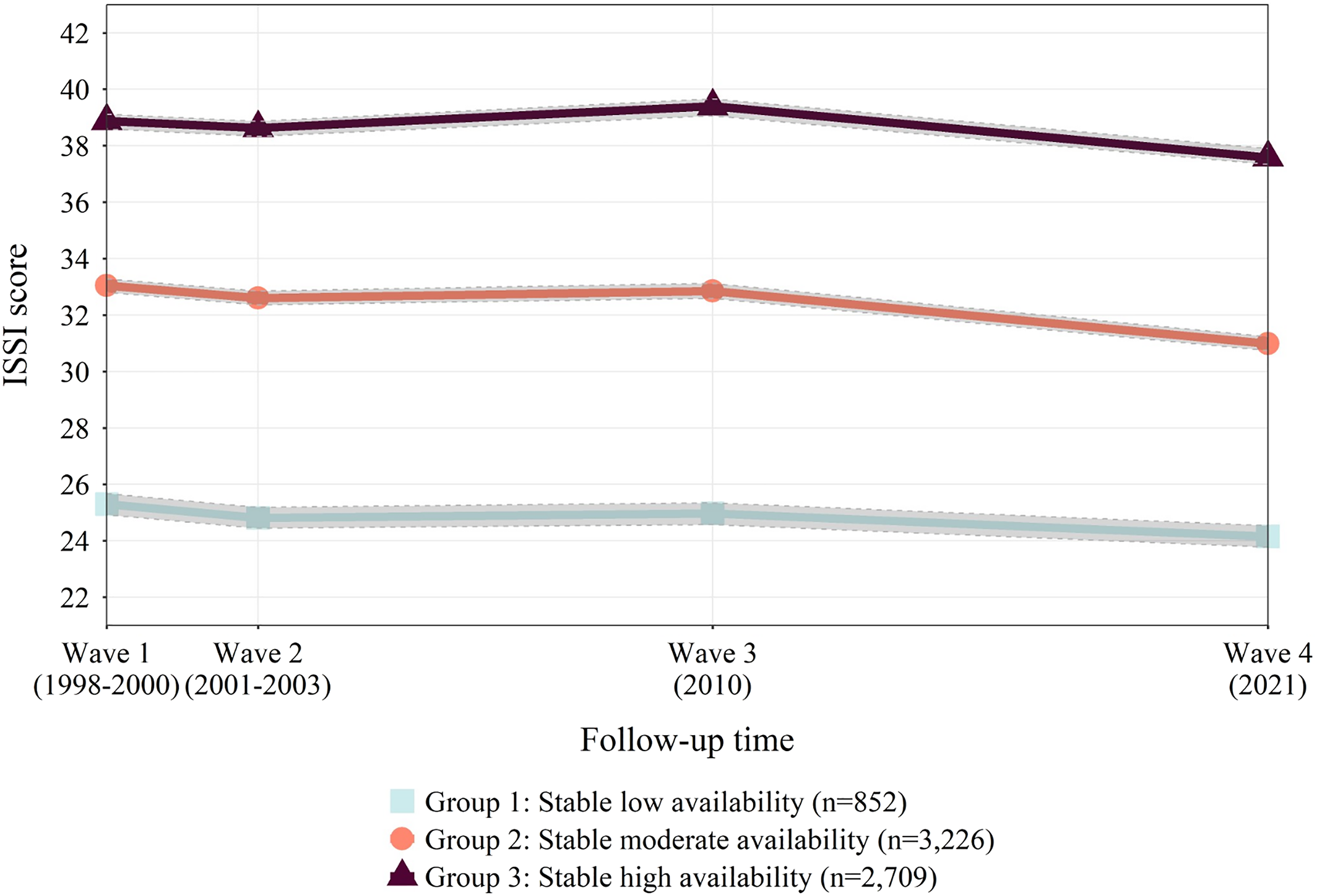

Trajectories of Social Support

The final trajectory model for social support with the best model fit included three trajectories (Supporting Information

S1: Supplement H). The social support trajectories were: stable low availability (12.6%,

n = 852), stable moderate availability (47.5%,

n = 3226), and stable high availability (39.9%,

n = 2709). Social support trajectories were relatively stable over time but slightly decreased in wave 4 (2021) for all three trajectory groups correspondingly (

Figure 2).

The characteristics of participants all significantly differed among the trajectory groups of social support. Sixteen percent of men were categorized as having “stable low availability,” compared to 10.1% of women. Furthermore, 36.6% of men were categorized as having “stable high availability” of social support, compared to 42.3% of women. Compared to the other trajectories, those with trajectories of “stable low availability” were older, less likely to be high/intermediate level salaried employees, more likely to live alone, and more likely to have experienced childhood adversities or stressful life events in the last year. They also had a significantly higher prevalence of depression (25.5%) compared to the “stable moderate availability” (8.1%) and “stable high availability” (3.9%) groups. Those with “stable low availability” were most likely to currently or previously have been treated for mental illness, most likely to report anxious distress, and most likely to currently take psychotropic medication. Furthermore, they reported the worst health status and most comorbidities (Supporting Information

S1: Supplement I).

Those with “stable low availability” of social support were less likely to follow the rules introduced by the authorities to limit the spread of COVID‐19 in wave 4, however, 56.5% still followed the rules at all times, compared to 60.4% of those with “stable high availability” (Supporting Information

S1: Supplement J).

Dual Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms and Social Support

Compared to all other trajectories of depressive symptoms, individuals with “no depressive symptoms” had the highest conditional probability to have a trajectory of “stable high availability” of social support (56.8%), whereas they had the lowest conditional probability to have a “stable low availability” trajectory of social support (4.7%). Conversely, those with a trajectory of “persistent depressive symptoms” had the lowest conditional probability to have a “stable high availability” trajectory of social support (8.3%) and the highest conditional probability to have a “stable low availability” social support trajectory (55.1%) (

Table 1).

The conditional probability of having a trajectory of “no depressive symptoms” was the highest in people with “stable high availability” of social support (71.7%). The conditional probability of having “persistent depressive symptoms” was the highest in those with “stable low availability” of social support (14.2%) compared to 0.7% of those with “stable high availability” of social support (

Table 2).

Association between Trajectories of Social Support and Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms

The odds of being in a worse trajectory group of depressive symptoms (i.e., a trajectory characterized by high symptoms and/or recurrence) were significantly higher for those with a social support trajectory of “stable low availability” compared to those with “stable high availability,” and these estimates did not change markedly after adjusting for confounders (

Table 3). People with “stable low availability” of social support had an odds of 40.59 (95% confidence interval: 22.70–75.58) of having a trajectory of “persistent depressive symptoms” compared to the “no depressive symptoms” group. Similar but slightly weaker associations were observed for a social support trajectory of “stable moderate availability.” There were no significant interactions with sex or age.

DISCUSSION

Principal Findings

Six distinct trajectories of depressive symptoms and three trajectories of social support were determined. Individuals with a trajectory of “no depressive symptoms” had the highest conditional probability of having a social support trajectory of “stable high availability.” Conversely, those with “persistent depressive symptoms” were most likely to have a social support trajectory of “stable low availability.”

Interpretation

Trajectories of depressive symptoms

Previous studies on trajectories of depressive symptoms are heterogeneous and found a variety of distinct groups (three to six). Trajectories varied also in terms of severity and stability, with stable low symptoms being the most common and persistent high symptoms the least common (typically <10% of participants) (

26). However, few of the studies were carried out in the general adult population. In this study, we identified more trajectory groups than were identified in other studies, however, the largest group still displayed stable low symptoms, and the smallest group showed persistent depressive symptoms. We identified a unique “slightly elevated depressive symptoms” group, distinct from “no depressive symptoms,” though its clinical relevance is uncertain as at no time point were the MDI symptoms increased to a level indicating depression.

Since group‐based trajectory modeling is a data‐driven analysis, specific trajectories depend on the study population, the timing of measurements, and the measurement scale. Additionally, our study is the first to investigate trajectories of depressive symptoms in a population‐based setting during the COVID‐19 pandemic which may have influenced reporting due to increased depression and anxiety prevalence during the pandemic in 2021 (

27).

Trajectories of social support

The three social support trajectories in our study align with those found in other studies (

28,

29). However, unlike the stable trajectories in this study, previous research showed fluctuations over time. These differences may arise from the specific sub‐populations in previous studies (e.g., older Mexican Americans, women), or the chosen time intervals for data collection.

In this sample, all social support trajectories slightly decreased in wave 4 (2021) which could have been related to the COVID‐19 pandemic and subsequent restrictions. Similar trends were observed in England and Canada (

30,

31). However, in Sweden, the social distancing restrictions were less strict than in most other countries, so responses might have been different. Participants with social support trajectories of “stable low availability” were less likely to adhere to COVID‐19 restrictions compared to those with “stable high availability,” however, details on the specific restrictions that were enforced were not collected.

Associations of trajectories of social support with trajectories of depressive symptoms

Trajectories of social support and depressive symptoms were highly associated in this study with indications of a dose‐response relationship. This finding aligns with existing research, as a 2016 systematic review reported similar associations between social support and depression that are consistent across different age groups (

32). Despite descriptive statistics suggesting some gender‐specific patterns, there were no significant interactions between social support and age or sex, contrary to other studies. This may be due to the complexity of sex‐specific differences in relationship quality and responsibilities, which the social support measure might not have fully captured (

33,

34).

The high magnitude of association between trajectories of social support and depression is likely due to bi‐directional associations. Correspondingly to social support affecting depressive symptoms, those with high depressive symptoms have less rewarding and more dysfunctional relationships and are more likely to withdraw from and spend less time in social interactions (

35,

36). While the true magnitude of the association cannot be judged based on the present results, other studies for example, in psychiatric care settings show that quantity and quality of social support were significant predictors of depressive symptoms at follow‐up in 150 middle‐aged and elderly depressed in‐patients (

9). Furthermore, in a Swedish longitudinal study, increased social support was associated with reduced depressive symptoms in men, while women experienced bi‐directional effects (

33).

Strengths and Limitations

The PART study encompasses a large population‐based sample and a prospective design with long‐term follow‐up. Moreover, the assessment of self‐reported symptoms with the MDI allows a relatively reliable assessment of depression according to the DSM‐IV and ICD‐10 (

20,

37).

However, the study also has several limitations. First, participants lost to follow‐up (i.e., those with low income, low education, and previous psychiatric diagnosis) were more likely to experience symptoms of depression (Supporting Information

S1: Supplement D), which might have led to an underestimation, especially of those with persistent depressive symptoms. In this study, we could not distinguish participants who were truly lost to follow‐up from those who were followed at all four waves but did not report MDI and ISSI scores in at least three and were consequently excluded.

Another limitation is that mental health treatment and psychotropic medication use were self‐reported which might underestimate the true situation of care and treatment. Furthermore, residual confounding, particularly by neuroticism, might exist, however, one study showed that social support predicted depression severity and recovery at follow‐up, even when controlled for neuroticism (

38).

Because the study only included participants with three or four measurements, the possible trajectory shapes were limited by the study design. Moreover, depressive episodes vary in occurrence and duration, making it challenging to define an optimal time lag. The chosen time intervals for measurement might, therefore, not best represent the course of depressive symptoms and social support.

Finally, this study examined the relationship between depressive symptoms and social support cross‐sectionally over time, so causal or directional claims about the relationship cannot be made.

CONCLUSION

This population‐based study showed that long‐term trajectories of depressive symptoms and social support are heterogeneous and highly associated over time in a Swedish adult population. Individuals without depressive symptoms are likely to have a stable high availability of social support, and those with persistent depressive symptoms are likely to have a stable low availability of social support. The findings imply that social support should be considered in the management of depressive symptoms, as interventions to enhance social skills in those with low social support can be effective strategies for reducing depressive symptoms, irrespective of the direction of the association (

39). The government has recently allocated significant resources to the public health agency to investigate ways to prevent loneliness, recognizing it as a major issue in Sweden. In clinical practice, it's essential to assess and enhance patients' social networks, often through community‐provided activities, especially for those with psychiatric conditions. Collaboration between the clinic, community representatives, and patients is key in developing personalized support programs, with a stronger focus on community care than clinical intervention.