20‐Year Trajectories of Substance‐Use Service Utilization by Ontario's Muslim‐Majority Country Immigrants

Abstract

Objective

Methods

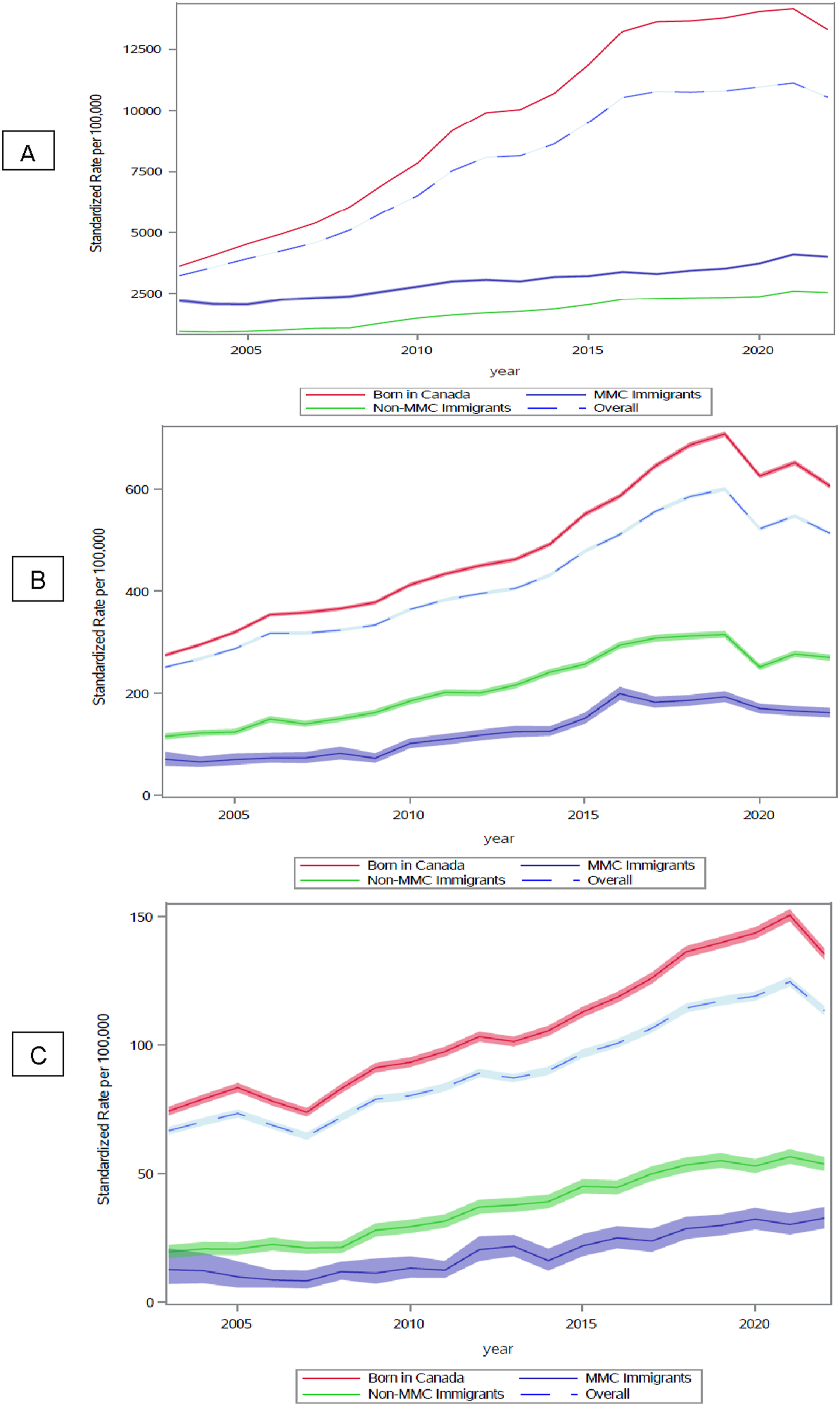

Results

Conclusions

Highlights

METHODS

Model Description

Outcome Measures and Exposure

Statistical Analyses

RESULTS

Demographics

| Variable | Values | 2003 | 2022 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMC > 50% | Non‐MMC < 50% | Individuals born in Canadab | p‐value | MMC > 50% | Non‐MMC < 50% | Individuals born in Canada | p‐value | ||

| Sample size | N = 243,756 | N = 1,243,023 | N = 10,723,613 | N = 561,937 | N = 2,138,307 | N = 12,178,607 | |||

| Age | Mean (SD) | 31.89 (16.44) | 36.82 (16.84) | 37.41 (22.55) | <0.0001 | 41.58 (17.61) | 46.42 (17.18) | 40.37 (24.12) | <0.0001 |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 32 (19–42) | 36 (25–46) | 37 (18–54) | 41 (29–54) | 46 (34–58) | 39 (20–60) | |||

| Age category | 0–5 | 8319 (3.4%) | 18,039 (1.5%) | 818,290 (7.6%) | <0.0001 | 3258 (0.6%) | 7866 (0.4%) | 869,969 (7.1%) | <0.0001 |

| 6–10 | 16,813 (6.9%) | 40,576 (3.3%) | 754,959 (7.0%) | 14,984 (2.7%) | 25,559 (1.2%) | 758,808 (6.2%) | |||

| 11–15 | 21,014 (8.6%) | 68,578 (5.5%) | 739,735 (6.9%) | 23,751 (4.2%) | 40,004 (1.9%) | 747,273 (6.1%) | |||

| 16–20 | 22,189 (9.1%) | 93,288 (7.5%) | 686,912 (6.4%) | 27,689 (4.9%) | 59,467 (2.8%) | 718,053 (5.9%) | |||

| 21–25 | 19,142 (7.9%) | 97,724 (7.9%) | 646,322 (6.0%) | 36,712 (6.5%) | 89,024 (4.2%) | 790,156 (6.5%) | |||

| 26–30 | 23,677 (9.7%) | 122,163 (9.8%) | 665,906 (6.2%) | 47,945 (8.5%) | 148,779 (7.0%) | 886,142 (7.3%) | |||

| 31–35 | 32,020 (13.1%) | 158,682 (12.8%) | 728,473 (6.8%) | 61,674 (11.0%) | 228,430 (10.7%) | 795,496 (6.5%) | |||

| 36–40 | 31,391 (12.9%) | 172,063 (13.8%) | 862,443 (8.0%) | 62,650 (11.1%) | 239,380 (11.2%) | 721,934 (5.9%) | |||

| 41–45 | 24,452 (10.0%) | 143,975 (11.6%) | 876,827 (8.2%) | 54,680 (9.7%) | 219,061 (10.2%) | 670,070 (5.5%) | |||

| 46–50 | 17,078 (7.0%) | 104,199 (8.4%) | 797,977 (7.4%) | 52,111 (9.3%) | 214,504 (10.0%) | 675,429 (5.5%) | |||

| 51–55 | 8959 (3.7%) | 65,790 (5.3%) | 731,081 (6.8%) | 50,306 (9.0%) | 213,642 (10.0%) | 714,012 (5.9%) | |||

| 56–60 | 5389 (2.2%) | 39,997 (3.2%) | 588,207 (5.5%) | 42,040 (7.5%) | 200,163 (9.4%) | 831,664 (6.8%) | |||

| 61–65 | 4292 (1.8%) | 33,295 (2.7%) | 461,134 (4.3%) | 31,752 (5.7%) | 157,392 (7.4%) | 785,156 (6.4%) | |||

| 66–70 | 3645 (1.5%) | 30,672 (2.5%) | 402,045 (3.7%) | 21,812 (3.9%) | 110,941 (5.2%) | 680,344 (5.6%) | |||

| 71–75 | 2781 (1.1%) | 24,360 (2.0%) | 360,129 (3.4%) | 13,162 (2.3%) | 75,918 (3.6%) | 594,086 (4.9%) | |||

| 76–80 | 1596 (0.7%) | 16,392 (1.3%) | 290,812 (2.7%) | 8110 (1.4%) | 46,507 (2.2%) | 401,314 (3.3%) | |||

| 81+ | 999 (0.4%) | 13,230 (1.1%) | 312,361 (2.9%) | 9301 (1.7%) | 61,670 (2.9%) | 538,701 (4.4%) | |||

| Sex | Female | 112,730 (46.2%) | 641,665 (51.6%) | 5,433,104 (50.7%) | <0.0001 | 277,593 (49.4%) | 1,127,657 (52.7%) | 6,140,799 (50.4%) | |

| Male | 131,026 (53.8%) | 601,358 (48.4%) | 5,290,509 (49.3%) | 284,344 (50.6%) | 1,010,650 (47.3%) | 6,037,808 (49.6%) | |||

| Area income quintile | Missing | 93 (0.0%) | 711 (0.1%) | 41,859 (0.4%) | <0.0001 | 1185 (0.2%) | 4208 (0.2%) | 30,445 (0.2%) | |

| 1—Lowest | 86,982 (35.7%) | 372,177 (29.9%) | 1,884,978 (17.6%) | 136,206 (24.2%) | 487,525 (22.8%) | 2,240,770 (18.4%) | |||

| 2 | 50,682 (20.8%) | 285,377 (23.0%) | 2,080,294 (19.4%) | 101,480 (18.1%) | 457,622 (21.4%) | 2,370,970 (19.5%) | |||

| 3 | 42,525 (17.4%) | 235,169 (18.9%) | 2,174,852 (20.3%) | 117,603 (20.9%) | 457,619 (21.4%) | 2,435,692 (20.0%) | |||

| 4 | 38,342 (15.7%) | 204,811 (16.5%) | 2,252,129 (21.0%) | 118,042 (21.0%) | 412,194 (19.3%) | 2,499,431 (20.5%) | |||

| 5—Highest | 25,132 (10.3%) | 144,778 (11.6%) | 2,289,501 (21.4%) | 87,421 (15.6%) | 319,139 (14.9%) | 2,601,299 (21.4%) | |||

| Generation | First | 243,756 (100.0%) | 1,243,023 (100.0%) | 10,496,500 (97.9%) | <0.0001 | 561,937 (100.0%) | 2,138,307 (100.0%) | 11,318,106 (92.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Second | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 227,113 (2.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 860,501 (7.1%) | |||

| Immigra‐tion category | Category not stated/Invalid | 0 (0.0%) | ≤ 5 | 10,723,052 (100.0%) | <0.0001 | 6 (0.0%) | 10 (0.0%) | 12,178,063 (100.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Immigrants | 186,921 (76.7%) | 1,052,018 (84.6%) | 531 (0.0%) | 396,985 (70.6%) | 1,842,899 (86.2%) | 480 (0.0%) | |||

| Refugees | 56,835 (23.3%) | 191,003 (15.4%) | 30 (0.0%) | 164,946 (29.4%) | 295,398 (13.8%) | 64 (0.0%) | |||

| Material resources quintile | Missing | 5035 (2.1%) | 23,944 (1.9%) | 303,305 (2.8%) | <0.0001 | 1252 (0.2%) | 5141 (0.2%) | 114,688 (0.9%) | <0.0001 |

| 1—Lowest | 43,265 (17.7%) | 219,870 (17.7%) | 2,255,299 (21.0%) | 93,734 (16.7%) | 333,124 (15.6%) | 2,618,178 (21.5%) | |||

| 2 | 37,281 (15.3%) | 198,183 (15.9%) | 2,163,405 (20.2%) | 130,322 (23.2%) | 445,618 (20.8%) | 2,690,785 (22.1%) | |||

| 3 | 39,610 (16.2%) | 213,929 (17.2%) | 2,090,558 (19.5%) | 119,324 (21.2%) | 464,260 (21.7%) | 2,438,369 (20.0%) | |||

| 4 | 43,834 (18.0%) | 246,060 (19.8%) | 2,017,618 (18.8%) | 97,238 (17.3%) | 419,174 (19.6%) | 2,154,379 (17.7%) | |||

| 5—Highest | 74,731 (30.7%) | 341,037 (27.4%) | 1,893,428 (17.7%) | 120,067 (21.4%) | 470,990 (22.0%) | 2,162,208 (17.8%) | |||

| House‐holds and dwellings quintile | Missing | 5035 (2.1%) | 23,944 (1.9%) | 303,305 (2.8%) | <0.0001 | 1252 (0.2%) | 5141 (0.2%) | 114,688 (0.9%) | <0.0001 |

| 1—Lowest | 36,771 (15.1%) | 237,823 (19.1%) | 2,099,538 (19.6%) | 162,004 (28.8%) | 638,828 (29.9%) | 2,500,521 (20.5%) | |||

| 2 | 29,060 (11.9%) | 178,030 (14.3%) | 2,276,365 (21.2%) | 93,502 (16.6%) | 348,977 (16.3%) | 2,333,131 (19.2%) | |||

| 3 | 34,642 (14.2%) | 199,419 (16.0%) | 2,180,779 (20.3%) | 76,689 (13.6%) | 295,325 (13.8%) | 2,324,341 (19.1%) | |||

| 4 | 60,424 (24.8%) | 274,733 (22.1%) | 2,084,727 (19.4%) | 83,479 (14.9%) | 320,005 (15.0%) | 2,321,263 (19.1%) | |||

| 5—Highest | 77,824 (31.9%) | 329,074 (26.5%) | 1,778,899 (16.6%) | 145,011 (25.8%) | 530,031 (24.8%) | 2,584,663 (21.2%) | |||

| Age and labor force quintile | Missing | 5035 (2.1%) | 23,944 (1.9%) | 303,305 (2.8%) | <0.0001 | 1252 (0.2%) | 5141 (0.2%) | 114,688 (0.9%) | <0.0001 |

| 1—Lowest | 94,256 (38.7%) | 419,487 (33.7%) | 2,223,436 (20.7%) | 247,855 (44.1%) | 822,971 (38.5%) | 3,148,161 (25.8%) | |||

| 2 | 59,725 (24.5%) | 291,022 (23.4%) | 2,113,647 (19.7%) | 117,281 (20.9%) | 468,833 (21.9%) | 2,345,638 (19.3%) | |||

| 3 | 36,190 (14.8%) | 220,131 (17.7%) | 2,137,423 (19.9%) | 80,102 (14.3%) | 328,173 (15.3%) | 2,147,329 (17.6%) | |||

| 4 | 26,086 (10.7%) | 160,384 (12.9%) | 2,017,734 (18.8%) | 66,407 (11.8%) | 280,930 (13.1%) | 2,092,317 (17.2%) | |||

| 5—Highest | 22,464 (9.2%) | 128,055 (10.3%) | 1,928,068 (18.0%) | 49,040 (8.7%) | 232,259 (10.9%) | 2,330,474 (19.1%) | |||

| Racialized and newcomer populations quintile | Missing | 5035 (2.1%) | 23,944 (1.9%) | 303,305 (2.8%) | <0.0001 | 1252 (0.2%) | 5141 (0.2%) | 114,688 (0.9%) | <0.0001 |

| 1—Lowest | 4239 (1.7%) | 39,727 (3.2%) | 2,033,369 (19.0%) | 7010 (1.2%) | 62,392 (2.9%) | 2,199,187 (18.1%) | |||

| 2 | 7298 (3.0%) | 61,281 (4.9%) | 2,254,875 (21.0%) | 21,734 (3.9%) | 120,754 (5.6%) | 2,313,967 (19.0%) | |||

| 3 | 17,411 (7.1%) | 114,322 (9.2%) | 2,144,068 (20.0%) | 52,754 (9.4%) | 235,561 (11.0%) | 2,298,146 (18.9%) | |||

| 4 | 49,019 (20.1%) | 263,406 (21.2%) | 2,094,887 (19.5%) | 142,191 (25.3%) | 511,276 (23.9%) | 2,491,425 (20.5%) | |||

| 5—Highest | 160,754 (65.9%) | 740,343 (59.6%) | 1,893,109 (17.7%) | 336,996 (60.0%) | 1,203,183 (56.3%) | 2,761,194 (22.7%) | |||

| Rurality | Missing | 90 (0.0%) | 492 (0.0%) | 7597 (0.1%) | <0.0001 | 1178 (0.2%) | 4094 (0.2%) | 25,905 (0.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Urban | 243,049 (99.7%) | 1,225,511 (98.6%) | 9,166,167 (85.5%) | 557,380 (99.2%) | 2,096,010 (98.0%) | 10,683,911 (87.7%) | |||

| Rural | 617 (0.3%) | 17,020 (1.4%) | 1,549,849 (14.5%) | 3379 (0.6%) | 38,203 (1.8%) | 1,468,791 (12.1%) | |||

| LHIN of patient residence | 1—Erie St. Clair | 10,354 (4.2%) | 29,239 (2.4%) | 601,974 (5.6%) | 22,297 (4.0%) | 42,957 (2.0%) | 624,780 (5.1%) | <0.0001 | |

| 2—South West | 6251 (2.6%) | 32,755 (2.6%) | 861,410 (8.0%) | 20,757 (3.7%) | 67,377 (3.2%) | 984,441 (8.1%) | |||

| 3—Waterloo Welling‐ton | 6199 (2.5%) | 43,653 (3.5%) | 622,453 (5.8%) | 25,478 (4.5%) | 99,628 (4.7%) | 753,631 (6.2%) | |||

| 4—Hamilton niagara Haldimand Brant | 10,880 (4.5%) | 61,399 (4.9%) | 1,259,099 (11.7%) | 35,513 (6.3%) | 136,604 (6.4%) | 1,390,628 (11.4%) | |||

| 5—Central West | 19,944 (8.2%) | 133,625 (10.8%) | 527,832 (4.9%) | 45,279 (8.1%) | 295,827 (13.8%) | 698,878 (5.7%) | |||

| 6—Mississauga Halton | 42,863 (17.6%) | 161,070 (13.0%) | 794,362 (7.4%) | 112,299 (20.0%) | 274,680 (12.8%) | 897,335 (7.4%) | |||

| 7—Toronto Central | 36,258 (14.9%) | 203,750 (16.4%) | 907,447 (8.5%) | 51,620 (9.2%) | 235,602 (11.0%) | 1,006,884 (8.3%) | |||

| 8—Central | 57,663 (23.7%) | 292,556 (23.5%) | 1,168,845 (10.9%) | 123,830 (22.0%) | 501,559 (23.5%) | 1,369,575 (11.2%) | |||

| 9—Central East | 31,268 (12.8%) | 200,256 (16.1%) | 1,211,737 (11.3%) | 69,369 (12.3%) | 303,710 (14.2%) | 1,322,041 (10.9%) | |||

| 10—South East | 994 (0.4%) | 7146 (0.6%) | 466,598 (4.4%) | 2851 (0.5%) | 16,282 (0.8%) | 516,014 (4.2%) | |||

| 11—Champlain | 19,928 (8.2%) | 63,657 (5.1%) | 1,075,815 (10.0%) | 46,026 (8.2%) | 119,319 (5.6%) | 1,290,046 (10.6%) | |||

| 12—North Simcoe Muskoka | 620 (0.3%) | 7097 (0.6%) | 396,207 (3.7%) | 4802 (0.9%) | 30,360 (1.4%) | 503,009 (4.1%) | |||

| 13—North East | 342 (0.1%) | 4033 (0.3%) | 581,524 (5.4%) | 1171 (0.2%) | 9930 (0.5%) | 581,629 (4.8%) | |||

| 14—North West | 192 (0.1%) | 2787 (0.2%) | 248,303 (2.3%) | 645 (0.1%) | 4472 (0.2%) | 239,714 (2.0%) | |||

| Primary care physicianc (virtually rostered) | 195,558 (80.2%) | 1,012,162 (81.4%) | 9,335,115 (87.1%) | <0.0001 | 416,719 (74.2%) | 1,503,637 (70.3%) | 8,029,607 (65.9%) | <0.0001 | |

Rate Ratios for Utilizing Substance Use Services in Ontario During 2003 and 2022

| Parameter | 2003 | p Value | 2022 | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate ratio (95% confidence interval) | Rate ratio (95% confidence interval) | |||||

| ED models | Immigration group | MMC versus Canadian born | 0.28 (0.24–0.332) | <0.0001 | 0.33 (0.306–0.358) | <0.0001 |

| Immigration group | Non‐MMC versus Canadian born | 0.51 (0.48–0.541) | <0.0001 | 0.54 (0.52–0.561) | <0.0001 | |

| Sex | Female versus Male | 0.44 (0.425–0.454) | <0.0001 | 0.488 (0.477–0.5) | <0.0001 | |

| Age | 1.003 (1.003–1.004) | <0.0001 | 0.99 (0.991–0.993) | <0.0001 | ||

| Hospital models | Immigration group | MMC versus Canadian born | 0.18 (0.122–0.254) | <0.0001 | 0.295 (0.254–0.343) | <0.0001 |

| Immigration group | Non‐MMC versus Canadian born | 0.341 (0.301–0.385) | <0.0001 | 0.477 (0.446–0.51) | <0.0001 | |

| Sex | Female versus Male | 0.461 (0.438–0.486) | <0.0001 | 0.459 (0.44–0.478) | <0.0001 | |

| Age | 1.01 (1.01–1.013) | <0.0001 | 1.0 (0.999–1) | 0.33 | ||

| Outpatient models | Immigration group | MMC versus Canadian born | 0.66 (0.599–0.718) | <0.0001 | 0.32 (0.31–0.34) | <0.0001 |

| Immigration group | Non‐MMC versus Canadian born | 0.23 (0.22–0.24) | <0.0001 | 0.24 (0.23–0.24) | <0.0001 | |

| Sex | Female versus Male | 0.49 (0.478–0.5) | <0.0001 | 0.501 (0.491–0.511) | <0.0001 | |

| Age | 0.963 (0.962–0.964) | <0.0001 | 1.006 (1.005–1.006) | <0.0001 |

Changes in Substance Use Services Utilization in 2022 Compared to 2003

| Canadian‐born | p‐value | MMC | p‐value | Non‐MMC | p‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate ratio (95% confidence interval) | Rate ratio (95% confidence interval) | Rate ratio (95% confidence interval) | |||||

| Emergency department visits | Year (2022 vs. 2003) | 2.008 (1.967–2.049) | <0.0001 | 2.404 (2.067–2.796) | <0.0001 | 2.093 (1.941–2.257) | <0.0001 |

| Hospitalization | Year (2022 vs. 2003) | 1.521 (1.482–1.562) | <0.0001 | 3.008 (2.064–4.384) | <0.0001 | 2.451 (2.117–2.838) | <0.0001 |

| Outpatient visits | Year (2022 vs. 2003) | 3.261 (3.209–3.312) | <0.0001 | 1.752 (1.528–2.01) | <0.0001 | 2.665 (2.506–2.835) | <0.0001 |

Ratio Rates of Repeated Visits for Substance Use Services Utilization in Ontario

| Substance services | Person‐years of observation | Number of unique individuals with service visit | Parameter | Rate ratio (95% confidence interval) | p‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency department | Canadian‐born: 3,685,375.6 | Canadian‐born: 403,381 | Immigration group | MMC versus Canadian born | 0.793 (0.771–0.816) | <0.0001 |

| MMC: 63,475.8 | MMC: 7872 | Immigration group | Non‐MMC versus Canadian born | 1.008 (0.995–1.021) | 0.2345 | |

| Non‐MMC: 307,063.0 | Non‐MMC: 35,462 | |||||

| Outpatients' visits | Canadian‐born: 8,450,486.7 | Canadian‐born: 804,953 | Immigration group | MMC versus Canadian born | 0.84 (0.818–0.862) | <0.0001 |

| MMC: 159,188.5 | MMC: 15,631 | Immigration group | Non‐MMC versus Canadian born | 0.552 (0.545–0.559) | <0.0001 | |

| Non‐MMC: 692,767.3 | Non‐MMC: 67,367 | |||||

| Hospitalization | Canadian‐born: 1,081,268.2 | Canadian‐born: 128,938 | Immigration group | MMC versus Canadian born | 1.102 (1.038–1.169) | <0.0001 |

| MMC: 9083.4 | MMC: 1305 | Immigration group | Non‐MMC versus Canadian born | 1.166 (1.14–1.193) | <0.0001 | |

| Non‐MMC: 65,274.9 | Non‐MMC: 8531 |

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSION

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

- Download

- 128.56 KB

REFERENCES

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).