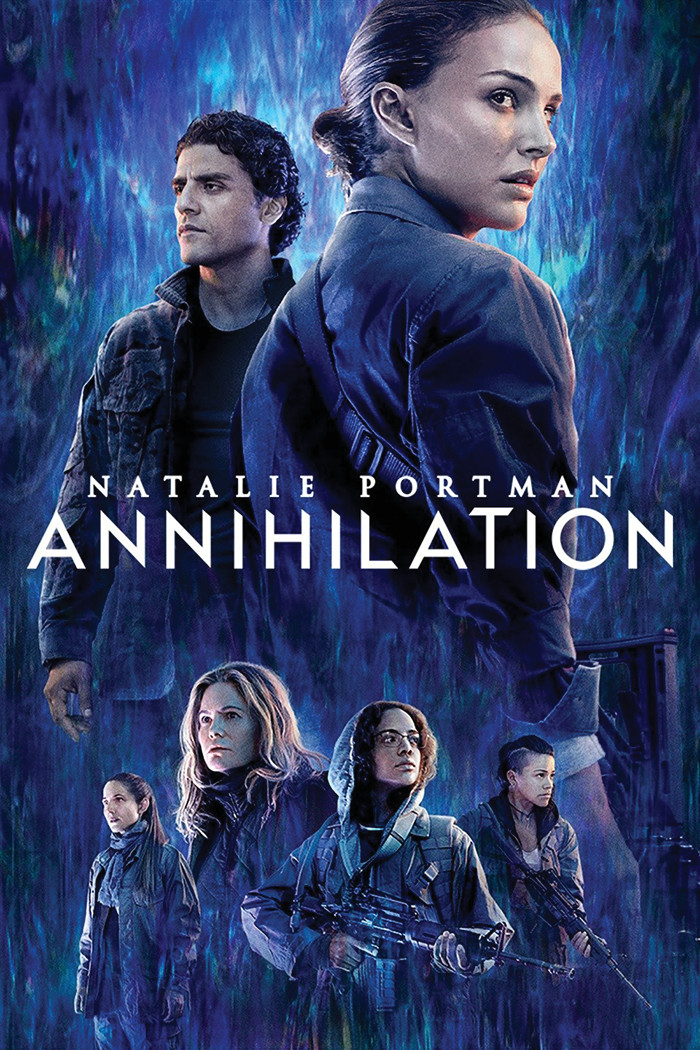

Falling off the sheer precipice of consciousness into the shocking and inexplicable world of the film Annihilation, starring Natalie Portman, and the Southern Reach Trilogy novels, written by Jeff VanderMeer, on which the film is based, is a pleasure that cannot be overstated. We enter Area X, an otherwise unremarkable stretch of the Gulf Coast, alongside a team referred to as the 12th expedition who go in to investigate. Various government agencies have spent decades attempting to discern the true nature of this expanse, which changed and now defies concrete description. We know that previous expeditions met with complete disaster. We know that this brought about odd protocols, such as referring to people by their role only. Portman, for instance, is The Biologist. No other name is given. The team includes an anthropologist, a linguist, a surveyor, and the team leader: the psychologist. Before now, only one person has ever made it back through the single known doorway. Others have returned by "transference": they were found back in their homes, outside Area X, apparently without ever leaving. Like the land, these "unfortunates" are changed. They are empty, flat, and unable to explain what they encountered except to say that it was "a pristine wilderness."

The film is quite different in structure and form from the trilogy but retains an essential and incomprehensible awe and horror, a shimmering spectacle that cannot be reduced through simple interpretation. It draws viewers in with stunning visual imagery that will keep them engrossed, misdirected even, while the plot slithers into their awareness, almost imperceptibly before crashing over top like a wave.

By contrast, the books pulse with a driving storyline that dares readers to stop reading, funnels them ever deeper, remaining punishingly intense, with the exception of a prolonged period of exposition in the second book. The writing flows as if from a faucet turned up just a little too high. Much like Area X itself, it is a pristine wilderness into which the reader must jump without preconception.

It appears to be an allegory for a psychoanalytic journey into the dark night of the soul, as though Area X represents the unconscious writ large—a place where unspeakable terrors normally consigned to the edge of awareness must be confronted in the clear light of day. Inside Area X, denial is irrelevant, its deployment dangerous. Metamorphosis is the rule rather than the exception. If you choose to approach these works, both the film and the book trilogy, you may find a uniquely potent mix of archetypal imagery made barely recognizable—aspects of self, named only by function, that converse, consider, and conflict. And, unlike other multipart works that build vast spaces of imagination but fail to achieve fulfilling catharsis, the Southern Reach Trilogy and the film Annihilation do not abuse the audience's willing suspension of disbelief—beautifully imaged, intellectually fulfilling, and emotionally gripping to the end.