Strokes are the most common cause of disability in the United States and have a well-known association with depressive symptoms (

1). In contrast, poststroke mania (PSM) is a rare occurrence, and little is known of the natural history of the disease. I present a case of a 53-year-old male with no previous medical or psychiatric diagnoses who experienced a cardioembolic stroke causing multifocal right frontal lesions that resulted in a subacute presentation of PSM, along with a brief literature review of previously published presentations and therapeutic strategies for PSM.

Case

Mr. E is a 53-year-old Caucasian male with no personal or family history of medical or psychiatric disease who presented to the emergency department of a large academic medical center with a single 20-minute episode of right upper extremity and lower extremity numbness associated with slurred speech. These symptoms resolved spontaneously prior to presentation. Of note, the patient had taken a 13-hour flight approximately 6 days prior to presentation. In the emergency department, a complete physical examination, a comprehensive metabolic panel, cell counts, thyroid function tests, electrocardiogram, and urinalysis with urine drug screening revealed no abnormalities. A noncontrast computed tomography scan of the head was without abnormality.

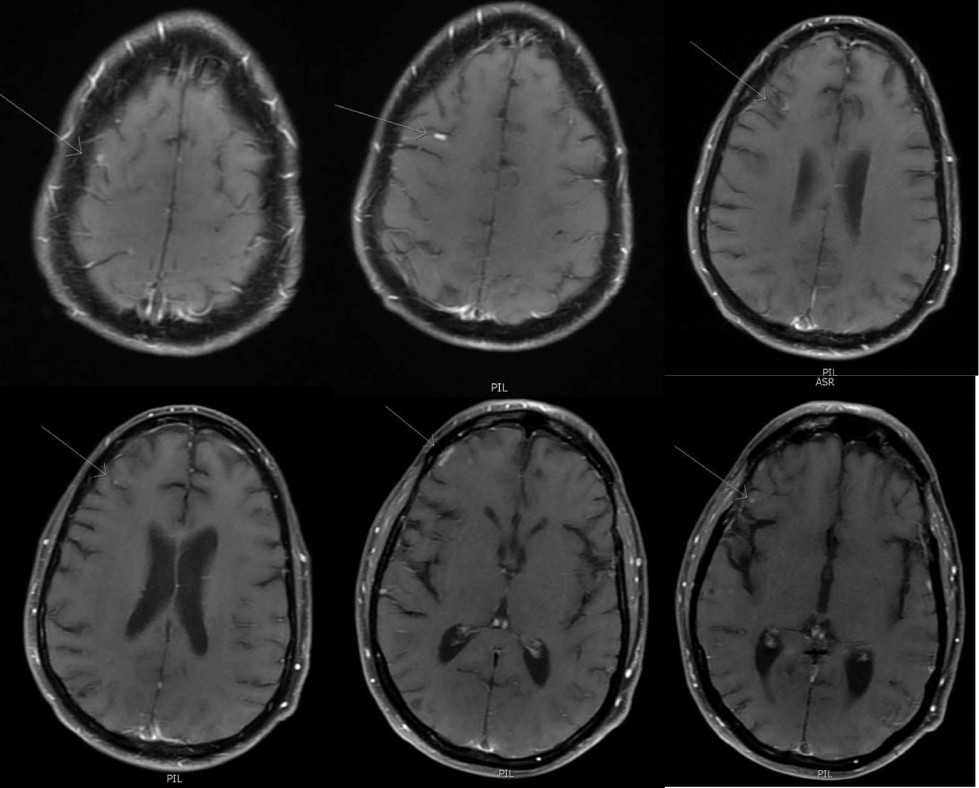

The patient was admitted to the neurology service for evaluation of a suspected stroke. A diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance image of the brain was obtained, which revealed a small focus of restricted diffusion in the left parietal lobe, thought to cause the presenting symptoms. In addition, the study revealed multiple frontal subcortical and cortical lesions in different stages of resolution, consistent with embolic phenomena (

Figure 1). A transthoracic echocardiogram was obtained, which was significant for microbubble evidence of interatrial shunt indicating a patent foramen ovale (PFO). A lower extremity venous Doppler study revealed a partially occlusive left popliteal thrombus. The patient was started on therapeutic anticoagulation with apixaban and discharged home to the care of his family. Cardiology was consulted and deployed a PFO closure device under conscious sedation within 1 week of hospital discharge.

A month later, Mr. E returned to the emergency department, brought in by his supervisor at work who reported that the patient had been demonstrating increasingly bizarre behavior at work and had threatened homicide on the day of second presentation. Collateral history obtained from his wife revealed a 3-week history of increasing irritability, hyperreligiosity (including a grandiose delusion of sainthood), and impulsive spending (approximately $30,000 on Catholic rosaries). His mental status exam was notable for rapid and pressured speech, tangential thought process, grandiosity, intrusiveness, and disordered impulse control. A repeat physical and laboratory evaluation was within normal limits. Repeat MRI imaging revealed stable lesions. Neurology evaluated the patient and had no recommendations for continued management, except for stroke risk factor modification. The patient was admitted to psychiatry with a diagnosis of PSM.

On the psychiatric unit, the patient was notably intrusive and impulsive but voluntarily accepted admission and pharmacologic treatment. Based on a review of available case data, treatment with valproate was offered to the patient, dosed without loading (250 mg twice daily) and titrated up over 1 week, increasing the total dose by 30% every 2 days to reach a target serum concentration of 70 to 100 mcg. This was achieved at a dose of 500 mg twice daily, after which the patient was found to have a steady-state serum concentration of 72 mcg. As-needed doses of orally disintegrating olanzapine tablets (10 mg) were administered for moderate to severe agitation; however, this occurred only once during admission. Over the next week of inpatient treatment, the patient had rapid resolution of religious delusions and speech abnormalities. On hospital day 12, the patient’s only persistent symptom was mild disinhibition, and he was discharged home on maintenance valproate with a plan for outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

Secondary Mania

Although the definite pathophysiology of primary mania continues to elude the field of psychiatry, secondary mania has been acknowledged as a phenomenon that can occur in association with many types of organic brain dysfunction. This includes neoplasms, seizures, infection, autoimmune disease, and metabolic disturbances, among other neurologic illnesses. Various ingestions and exogenous substances can produce a mania-like presentation that resolves once the substance is withdrawn. Because of the high morbidity of mania or a mania-like state, these cases should be rapidly identified using available diagnostic criteria and referred for treatment. Mania that persists once an illness has been treated or a substance has been withdrawn must be identified as either secondary mania or an exacerbation of latent bipolar disorder. Primary and secondary mania are difficult to distinguish clinically because of a lack of significant difference in frequency of core mania symptoms (

2). However, other signs that may suggest secondary mania include close temporal proximity to the organic insult, a negative premorbid history, predominantly negative family history, and late age at onset (

3).

Poststroke Mania

Poststroke neuropsychiatric syndromes are acknowledged as having immense clinical significance, inhibiting both physical and cognitive recovery following stroke. Poststroke depression is known to be the most common, with an estimated prevalence of 40% among stroke patients (

4,

5). In contrast, PSM has been described in the literature, although reports are much rarer. Current estimates of prevalence are between <1% and 1.6% among stroke patients, although this estimation is limited by small sample sizes, sparse literature, and likely underrecognition of the disorder (

6,

7).

In a case series of 49 patients, 76% of strokes that were linked temporally to a presentation of mania presented in the first month following stroke. The remaining 24% presented between 1 month and 2 years following stroke. Generally, presentations seemed severe, with 58% of patients presenting with more than five symptoms of mania, although functional disruption was not quantified (

6).

Pathophysiology and Neuroanatomic Correlates

Typical patients are described as male, without personal history of psychiatric disorders, with at least one risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and with a right hemispheric lesion. Specifically, as is seen in the case presented above, a higher correlation of PSM was seen with right hemispheric lesions affecting areas connected to the ventral limbic circuit, including the orbitofrontal cortex, basotemporal cortex, dorsomedial thalamic nucleus, and the head of the caudate nucleus (

2,

8,

9). It has been suggested that subcortical lesions (e.g., head of the caudate, thalamus) are more likely to produce bipolar symptoms, whereas cortical lesions (e.g., orbitofrontal and basotemporal cortices) are more likely to produce unipolar mania (

10).

The orbitofrontal circuit (OFC) is a complex network that plays a central role in mood regulation and social behavior, particularly in social inhibition. In functional imaging studies of patients with primary bipolar disorder during a manic episode, task-related right hemispheric OFC attenuation has been observed and hypothesized to be related to disinhibition in the disorder (

11). This suggests some overlap in the affected brain function of patients with primary mania and PSM. It should be noted, however, that case reports exist of patients who present with PSM or disinhibition and are found to have left hemispheric lesions, suggesting that our understanding is still incomplete (

12–

14).

Among published reports, our case was the only described case of multifocal cardioembolic stroke precipitating PSM. This case raises the question of whether multiple lesions to important limbic structures place patients at greater risk of developing PSM. This should be further explored in the future.

Treatment

No expert guidelines or consensus exist regarding the most effective way to treat patients with PSM. Published case series suggest approaches that range from inpatient monitoring without pharmacotherapy to a wide range of treatments with second-generation antipsychotics or anticonvulsant mood stabilizers. In most published cases, psychotropic medications were employed. In the largest case series, mood stabilizers were used in 62%, first-generation antipsychotics in 32%, second-generation antipsychotics in 19%, and benzodiazepines in 13%, although there were scarce data on dosages and efficacy (

6). There have been no placebo-controlled, blinded, or head-to-head trials to provide evidence-based treatment recommendations for PSM.

In my review of the literature, the most successful treatment among case data seemed to be valproic acid (

15). Lithium was avoided, despite some favorable results, because of controversy over its use in patients with cerebral lesions (

9). Benzodiazepines can be used as adjunctive treatments for hyperactivity and insomnia. No outcome data were found to describe the natural history of the disease and to suggest duration of treatment.