The photographer Larry Clark documented amphetamine use in his hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma, between 1963 and 1971. These images were ultimately published in the 1971 photobook

Tulsa (

1). Clark's evolving photographic approach throughout the making of

Tulsa illustrates the basic challenge of using artistic expression to shine light on drug addiction. Clark began as a naive participant in the world of amphetamine use with no political goals, and at this stage, he was able to show the viewer a nuanced, human portrayal of addiction. As Clark became more motivated to tell a captivating story, however, he became distant from his subjects and cast people using drugs as anonymous and depraved. Martin Parr and Gerry Badger (

2) have observed this paradox elsewhere in photography of drug use: "The problem with such a project, where the photographer intrudes upon an enclosed world, especially a world regarded as transgressive, is the dichotomy between voyeurism and the need to know." Can those working to address today's drug crises, including psychiatrists, avoid Clark's pitfalls?

Amphetamine began as a drug without a diagnosis. Benzedrine, the first amphetamine available in the United States, came to market in 1933. The drug's initial indication was nasal congestion, but its more potent effects of mood elevation and appetite suppression led to amphetamine's success as an antidepressant and weight-loss medication. The drug's popularity grew, in part due to pharmaceutical companies' denial of its addictive potential. In the 1940s, many in the medical community asserted that amphetamines caused habituation rather than addiction (

3,

4). Despite prevailing attitudes, a handful of prescient psychiatrists published on the deleterious effects of amphetamine. In 1947, American military psychiatrists documented widespread misuse of stimulant inhalers in a military prison, finding that discontinuation of the drug reliably precipitated withdrawal (

5). In 1957, a British psychiatric trainee published a groundbreaking series of 42 cases of amphetamine addiction, many with drug-induced psychosis (

6). As evidence of amphetamine's addictiveness mounted, the drug's supporters shifted blame to those with addiction. By the 1960s, billions of tablets of amphetamine were produced each year, and illicit use swelled. Recreational users were derogatorily termed "speed freaks" (

3,

4).

In Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1963, methamphetamine was easily accessible in the form of Valo inhalers, which sold over the counter for 75 cents. Clark and his friends injected the drug daily. The photographs in the first section of

Tulsa were shot in 1963. During this time, Clark was a local teen with a camera and with no pretense of creating a coherent narrative for public consumption. He wanted to document the amphetamine use that was being ignored by much of the mainstream culture and medical community. "I started photographing my friends in this secret world that nobody else could have possibly come in and done except someone from the inside like me," Clark mused (

7).

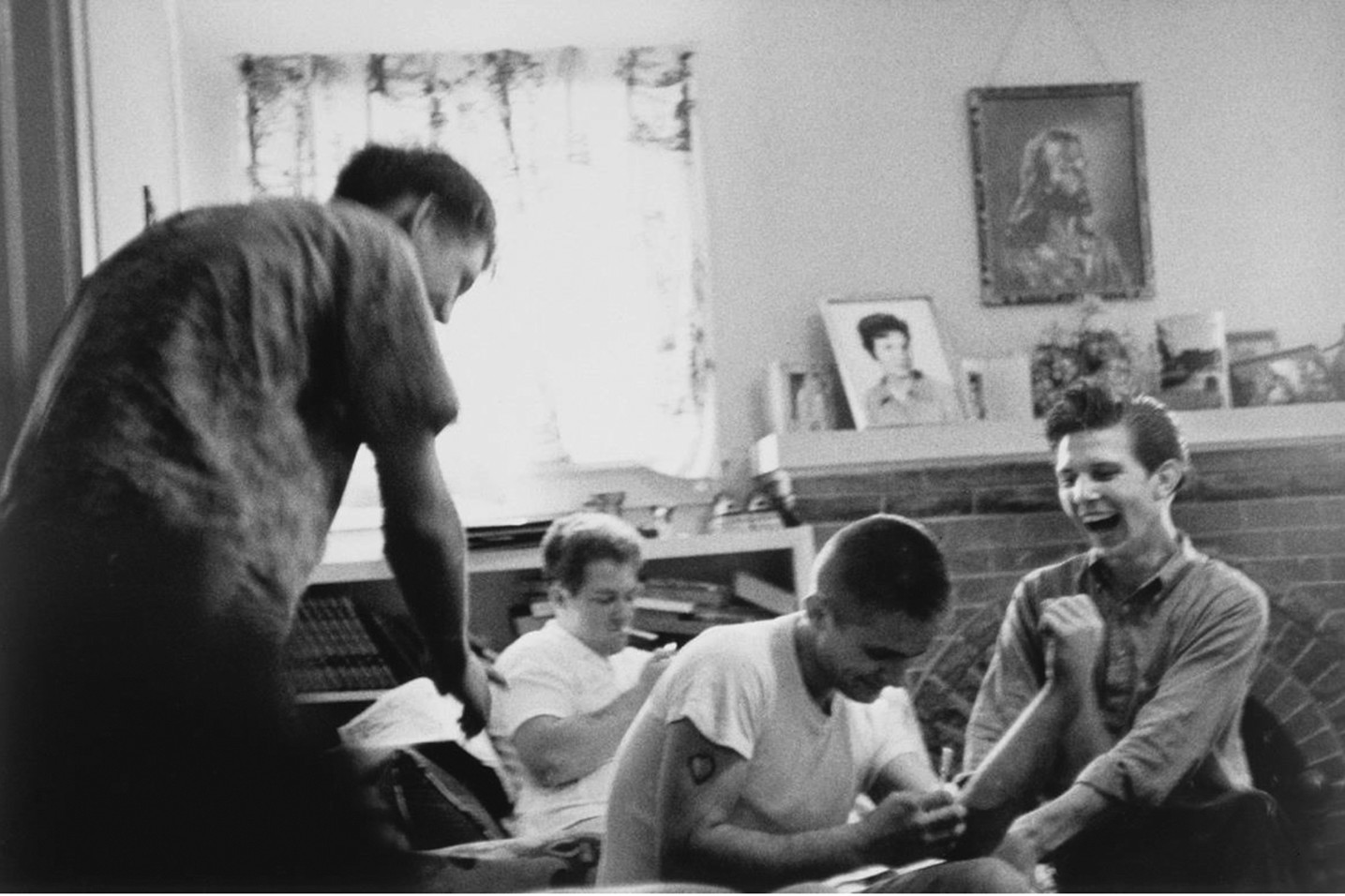

The untitled photograph from 1963 (

Figure 1) depicts the only two named characters in the book, David Roper and Billy Mann. Roper injects speed and smiles. Mann is laughing. The focus is on their relationship. The pair is clean cut. In the background, there is a neat mantel with family photos and a portrait of Jesus above the fireplace. With this quaint setting, Clark dismantles the façade of a perfect suburbia, complicating racist and classist stereotypes about people who use drugs. He explained, "There wasn't supposed to be drugs back then…. It was supposed to be mom's apple pie and white picket fences" (

7). Formally, the photograph is grainy and taken up close, at the level of his subjects. There is a casual lack of judgment, a passive participation, in the way the photograph is composed (

1).

During the mid-1960s, the dangers of amphetamine entered the public consciousness. The poet Allen Ginsberg campaigned against speed as early as 1965. In 1967, the gruesome murder of Linda Fitzpatrick at the hands of an amphetamine user brought national attention to the issue and began shaping the sensational notion of the monstrous "speed freak" (

4). Even the most progressive physicians bought into dehumanizing stereotypes. Dr. David Smith, the founder of the Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic, a novel integrated-care clinic aimed at young people who used drugs, cast "speed freaks" as frightening (

8). In his 1969 testimony before the U.S. Senate, he singled out amphetamine as "the most dangerous drug," one that "produces violence" (

9). The only widely available medication for the treatment of acute amphetamine psychosis was chlorpromazine.

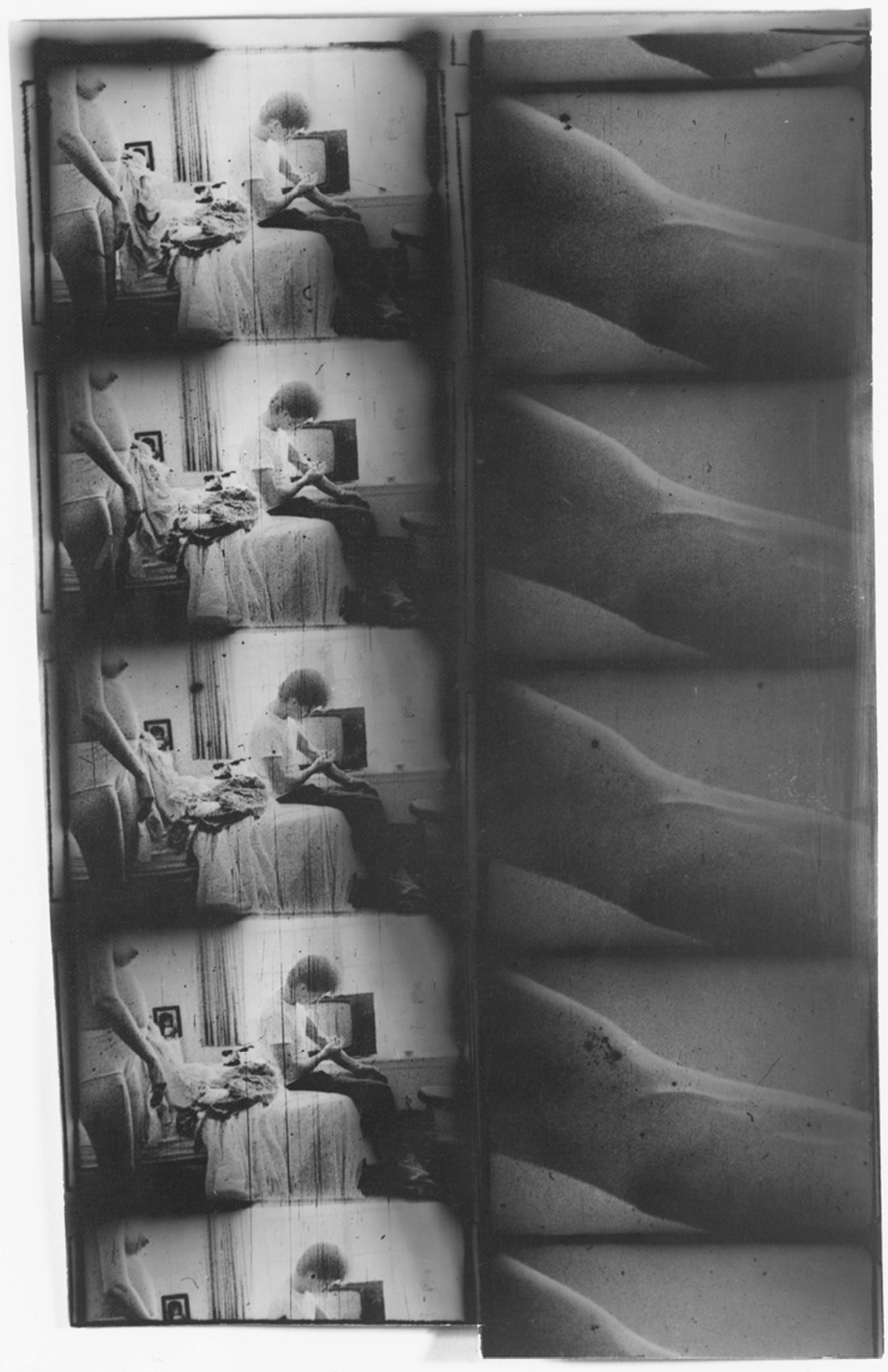

In 1968, Clark returned to Tulsa with a 16-mm movie camera, and the photos from that year are mostly scraps of movie film. These photographs depict subjects in a more distanced and dehumanizing way that echoes the negative cultural discourse around amphetamine at the time. In the left panel of the untitled photograph from 1968 (

Figure 2), a man is sitting on an unmade bed, injecting amphetamine. A pregnant woman looks on. On the right, there is a disembodied arm with a bulging vein. Clark's emphasis has turned from unique human portraits to gruesome repetition and anonymity. We are unable to viscerally connect to these people, because we do not see who they are. Faces are obscured or cut off, and the film itself is so gritty that the details are lost. Clark distances himself and the viewer from the subject, presenting the images as ephemera rather than worlds we are invited to enter (

1).

After his 1968 stint, Clark began to lay out his still-unpublished photographs with the goal of producing a photobook. He then returned to Tulsa once more in 1971 to complete his vision. He said he went back "knowing exactly what photographs I needed that I didn't have" (

7).

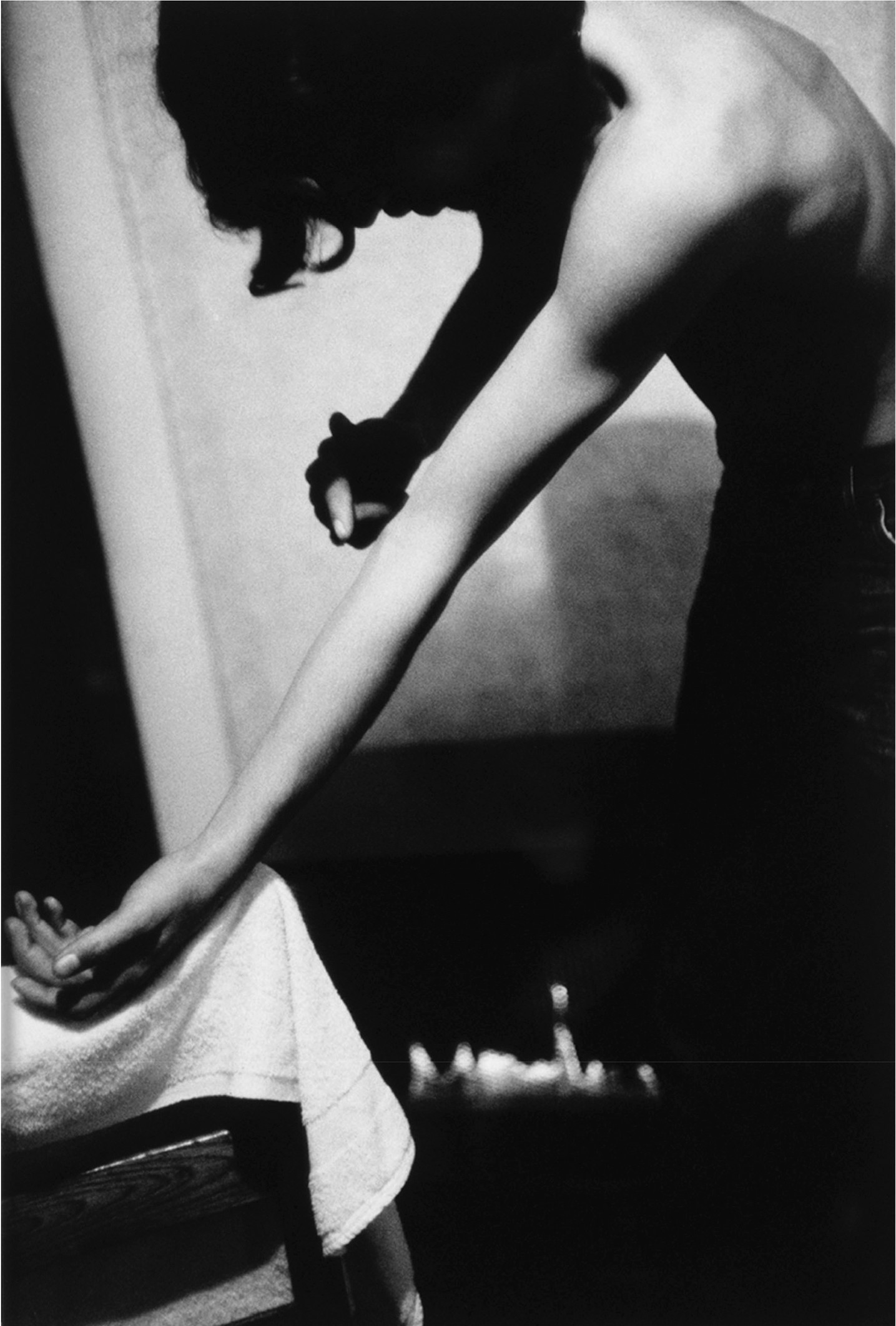

In the final image of

Tulsa from 1971, we see an unnamed young man with his arm resting, pointing to his bulging vein (

Figure 3). His face is hidden in shadow, but we can see his clean, unadulterated arm. He is an abstraction. Clark's aim with this section was to convey that drug abuse is a cycle. He explained, "It starts when we're kids and it ends with … the next generation, 15, 16-year-old kids, so it's like a circle. It just goes on and on, it's still going on" (

7). This is a powerful, allegorical image. There is something wrenching about seeing this vital young man about to devolve into amphetamine addiction (

1).

On the other hand, how "true" is this image? When Clark was just a kid in 1963, photographing his friends, he could see them as whole people. However, by the time he was completing Tulsa in 1971, he had a preconceived narrative to convey, and his subjects appear as symbols rather than individuals.

Tulsa caught the attention of Dr. Lester Grinspoon, a psychiatrist who wrote extensively on amphetamine addiction and used

Tulsa to illustrate the ravages of speed in a 1972 medical article. Grinspoon believed that

Tulsa was capable of educating a medical audience on amphetamine addiction and its social consequences. He wrote, "I am doubtful that even the best use of a word medium would allow for the creation of as stark and poignant a confrontation with this American tragedy as does

Tulsa." Grinspoon speaks to

Tulsa's power as a political document—one that could have real influence beyond the art world (

10).

Photography allows us to see the unseen, but there is a tension between truth and manipulation. In the case of Clark, the 1963 images in Tulsa succeed as art activism, because he showed drug use as just one facet of his subjects' complex lives. In later photographs, Clark's approach was that of an auteur, using his subjects to illustrate a preconceived narrative. Clark's work illustrates that when the photographer attempts to understand the richness of his subjects' lives, the narrative is authentic and complex, allowing for an empathic connection between viewer and subject.

This connection is also fundamental to our work as psychiatrists. On a typical day in the emergency department, my colleagues and I evaluate dozens of patients in states of drug intoxication and withdrawal, intermingling with mood disorders and psychosis. Substance use is the rule rather than the exception. There are small victories: a young woman goes to rehab newly initiated on buprenorphine; another's methamphetamine-induced paranoia clears. But more often, patients cycle in and out, stuck in a bewildering limbo.

One would hope that engaging with this tragedy day in and day out over the course of residency would lead to a deeper empathy toward people with substance use disorders. Worryingly, the opposite is true: research reveals that as psychiatry residents progress in their training, their views of patients with addiction become more negative (

11).

Rather than relying on assumptions or stereotypes, those of us who treat substance use disorders must be flexible in our understanding of who might use drugs and why. We must approach each patient as an individual, and art can help us to do so. When I sit down with a patient to talk about his or her substance use, I look for specifics, as Clark did in 1963. I try to piece together a full story; I learn names, relationships, and contexts. On face, these details can seem peripheral, but they are what bind me to my patients.