The experience of major neurocognitive disorders has always been difficult for me to conceptualize. Clinically, I know they involve memory loss and decreasing neurocognitive function, but understanding how someone with such disorders feels seems unimaginable. In the drama “The Father,” a 2020 film cowritten and directed by Florian Zeller, we are allowed into the fractured mind of Anthony Hopkins’ character, purposefully named Anthony, an 80-year-old Londoner struggling with dementia. Inspired by the cognitive decline of Zeller’s grandmother when the director was a teenager, the film forces us to experience the impairments caused by dementia. Anthony’s confusion becomes our own as contradicting memories and scenes make both the character and the viewer question their experiences. The film not only gives a firsthand account of how it feels to succumb to dementia, but it also shows us the heartbreaking ramifications of dementia for the loved ones who must also endure this horrifying condition.

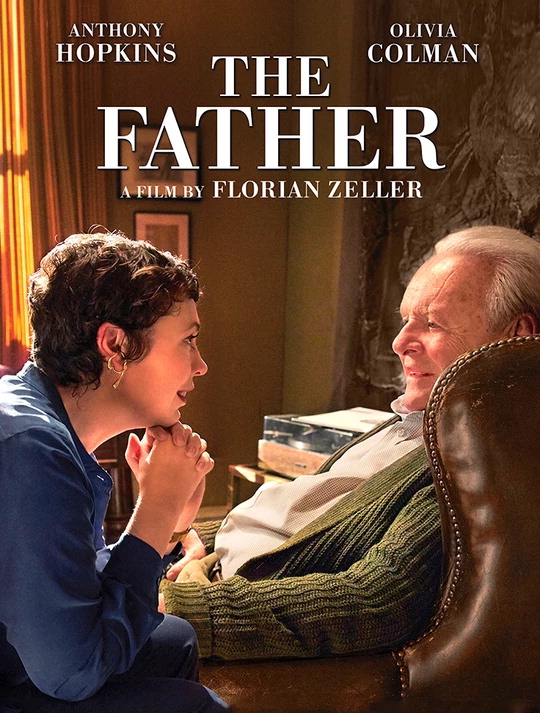

Hopkins’ performance is outstanding as expected. He completely disappears into his role; masterfully switching midscene from a charismatic, flirtatious gentleman when he meets the latest young female caregiver his daughter has hired to a paranoid and resentful man when he falsely suspects his daughter of conspiring against him. Countering Hopkins is Olivia Colman, who plays Anthony’s daughter, Anne. Colman goes toe to toe with Hopkins and matches his performance perfectly. She uses extreme precision in her craft, holding back tears, but mustering a smile to hide her pain as her father insults her in front of a caregiver.

While the performances of Hopkins and Colman are surely some of the greatest of their careers, what really makes the film outstanding is the set design and direction. Throughout the film, the set utilizes the same skeleton of rooms, hallways, and windows. Zeller uses subtle changes in the setting to give the viewer a sense of familiarity, yet something always feels amiss. The tiles on the kitchen wall change from green to blue, the wall art is rearranged, then taken away. The door to the doctor’s office is the same as the apartment, but is it Anthony’s apartment or his daughter’s? Or have we been in a hospital this whole time? Zeller deepens the confusion by casting multiple actors and actresses to play the same character. Just when you think you have found some footing, Anne is suddenly played by Olivia Williams instead of Olivia Colman. Then, Williams goes on to play a caretaker and later also the nurse in a hospital. All these elements are masterfully orchestrated, drawing in viewers until it feels as if you are the one with the disorder.

As a clinician, I treat patients with dementia, and “The Father” gave me a taste of the brutality of the disorder. Feeling paranoid becomes an obvious consequence of never knowing your environment, never mind the people in it. Stripped of memories and executive function, one is left only in the present, unable to recall the past or predict the future. The film inspired me to reflect on my experiences with patients whose family members likely endured experiences similar to Anne’s. Although finding a safe living situation for patients with dementia can be frustrating, we must understand how horrifying it is to experience the disorder. And although it is clinically important to test patients’ memory and orientation, being present and patient with them should take precedence. In the powerful final scene, we witness the anguish of Anthony as he weeps into the arms of his caretaker calling out for his mother. It serves to remind us that, ultimately, what people yearn for most are love and compassion.