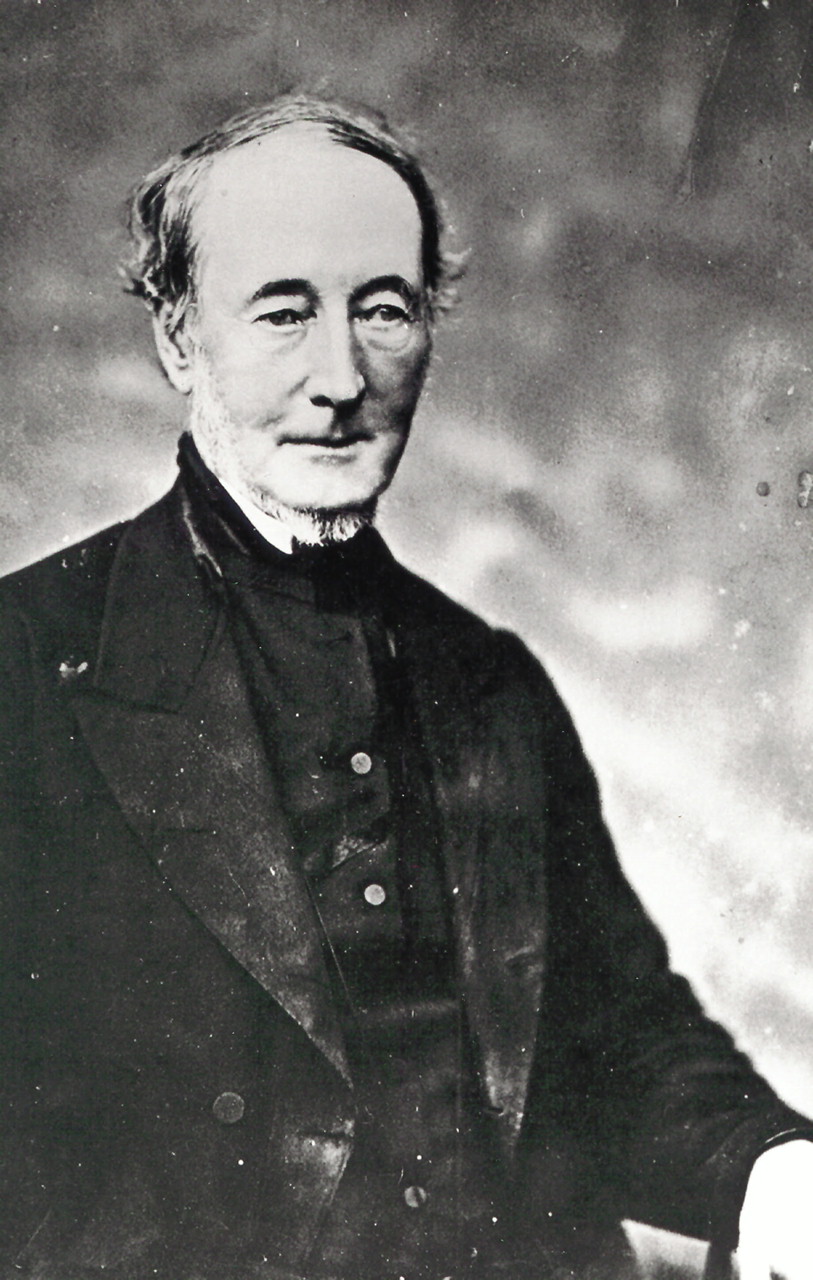

Appointed medical superintendent of the Toronto Asylum in 1853,

Joseph Workman set about reforming the institution and sweeping clean the previous regime’s legacy of mismanagement. Armed with a new Asylum Act, which restricted the (often political) interference of the directors, Workman restored order and efficiency and was soon recognized as an administrator of uncommon talent. He embraced the tenets of moral therapy, and good food, moderate exercise, worthwhile employment, and a healthy environment figured prominently in his curative regime. With his patients’ physical health improving, their mental health could not be far behind, and Workman was confident that a predicted 90% cure rate would soon be achieved.

Early optimism was soon dashed as it became obvious that the potential of asylum care had been vastly overrated. Loath to admit defeat, Workman claimed that early asylum promoters had created unrealistic expectations in the public mind. More serious were his charges that the province was using the asylum as a convenient dumping ground for society’s undesirables. “Obvious incurables” had no place in the asylum, Workman believed, for they took up valuable space and kept away patients with acute cases who would truly benefit from timely treatment. Furthermore, Workman criticized the government for chronically insufficient funding. Severe overcrowding prevented the sort of classification necessary for proper treatment and, without money for much-needed expansions, the proper maintenance of patients—to say nothing of a cure—would be impossible. Money was eventually forthcoming, and the Toronto Asylum expanded, as did the entire provincial system. But government largesse was not unconditional. Throughout the 1860s, Workman attempted to prevent the criminally insane, senile, and “obviously incurable” from entering his asylum. It was a battle that he was ultimately to lose, for as the inspector of asylums made clear, continued state support both for the asylum system and the psychiatric profession itself was dependent on unquestioning acceptance of a government policy that emphasized acquiescence to the wishes of the community over issues of treatment, protection, and advocacy for mentally ill individuals.

Although publicly praising the work of the provincial asylum service, Workman retired in 1875, frustrated by the demands of the government and its increasing tendency to medicalize—and thus depoliticize—social problems of the day. Recognized as the father of Canadian psychiatry, Workman was a tireless reformer who devoted his life to the interests of mentally ill patients. More important, however, his career demonstrated the ambiguities of nineteenth-century, asylum-based psychiatry, caught between a desire to cure and the need for state support and professional legitimization.