Kraepelin described dementia praecox as a variable but progressively dementing disorder with brain pathology

(1,

2). Severely disturbed patients with a chronic deteriorating course of schizophrenia have been observed less frequently in recent years

(3,

4), perhaps because neuroleptic treatment, now started early in the course of illness, may not only suppress psychotic symptoms but also influence the course of illness. Some researchers believe that medication may do far more than previously thought by preventing an active toxic brain process to continue (reviewed in Wyatt [

5,

6]). In 1986, Crow and colleagues

(7) published results from a randomized controlled trial of a standard neuroleptic for maintenance treatment after a first hospitalization for schizophrenia. Unexpectedly, the most important determinant of relapse was duration of untreated psychosis before the start of neuroleptic medication. Wyatt and colleagues, in reviews of the first neuroleptic treatment trials

(5,

6,

8,

9), concluded that early treatment does alter the course of illness. They noted significantly better outcomes in studies of first-episode patients, compared with outcomes reported in studies of neuroleptic trials with patients who had a chronic illness. Other studies have found that longer duration of untreated psychosis is related to longer time to remission, a lesser degree of remission

(10), poorer social and work functioning before the first admission, a more insidious onset of psychosis, and more negative symptoms at first clinical presentation

(11,

12). McGlashan

(13) has asserted that an extensive duration of untreated psychosis is a major public health problem.

Brain structural abnormalities are detectable in patients with schizophrenia at the time of the first hospitalization. These abnormalities include ventricular enlargement, loss of cerebral asymmetries, and regional cortical and nonlocalized reductions in gray matter volume

(14–

23). Neuropsychological deficits, which could provide a window into underlying brain pathology, similarly are known to be present by the time of the first episode. In particular, deficits in language, memory, executive function, and overall intelligence measures have been noted

(24–

29). Although cognitive processing has not been shown to deteriorate after the first hospitalization

(26,

30,

31), some studies have provided evidence that brain structural changes may be progressive after illness onset in some patients (reviewed in reference

32). In fact, early pneumoencephalographic studies revealed ventricular enlargement over time in patients with poor prognosis

(33–

35). As early as 1983, Woods and Wolf

(36) proposed that ventricular enlargement in schizophrenia as seen on computerized tomography scans was progressive. Unfortunately, these studies were ignored because schizophrenia was generally viewed as a neurodevelopmental disorder

(37) and little thought was given to the idea that the disorder could have both developmental and progressive components

(38,

39). Earlier findings that poor premorbid adjustment was associated with ventricular enlargement were interpreted to imply the existence of a subgroup of patients with an early developmental defect, rather than to suggest the possibility of an underlying progressive brain pathology that was responsible for the poor premorbid signs

(40,

41).

The study reported here tested the hypothesis that symptoms of schizophrenia before a first hospitalization, perhaps reflecting an active brain disturbance toxic to neuronal growth and repair, would result in cognitive and structural brain defects. Thus, increasing duration of untreated illness would be correlated with increasing deficits in cognitive performance and brain structural deviance at the time of first hospitalization. Since our previous studies

(42) and those of other investigators (reviewed in reference

32) have shown progressing ventricular enlargement and hemispheric and temporal lobe volume reductions in subjects with first-episode schizophrenia, we chose these three variables as indicators of brain structural change and correlated their values at the first hospitalization with duration of untreated illness. Similarly, we correlated duration of untreated illness with patients’ scores on a battery of neuropsychological tests that has been used previously to show generalized cognitive deficits at the time of a first episode

(24).

Method

Fifty patients with a first episode of schizophrenia who were consecutively admitted for hospitalization in Suffolk County, N.Y., participated in a longitudinal follow-up study that included an annual battery of clinical and neuropsychological evaluations and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. Structured psychiatric interviews with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L)

(43) were conducted by trained research staff. DSM-III-R diagnoses were made by a research psychiatrist after review of the SADS-L results, medical records, and structured interviews with family members about the patient’s symptoms. The diagnoses were confirmed by a second diagnostician. When there was a disagreement, a third diagnostician was consulted, and a consensus diagnosis was made. Diagnosticians were blind to the MRI results and neuropsychological test data. Of the 50 patients, 32 were diagnosed with schizophreniform disorder, six with subchronic schizophrenia, four with chronic schizophrenia, seven with schizoaffective disorder, and one with psychosis not otherwise specified. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects for all evaluations by using separate consent forms that had been previously approved by the State University of New York at Stony Brook. Additional details about the subjects are provided elsewhere

(24,

30,

42,

44).

Thirty-two men and 18 women with a mean age of 27.4 years (SD=7) participated in the study. MRI scan measurements previously obtained from 20 healthy comparison subjects (12 men and eight women, mean age=26.5 years, SD=5)

(38) were used for calculating Z scores, as described below.

For each patient in the study, initiation of treatment occurred on admission to the hospital. Two estimates of duration of untreated illness were derived from information on the patient’s psychosocial and developmental history that was obtained in structured interviews with the patient and the closest available family member. The first estimate was the duration of untreated psychosis, assessed as the duration (in months) of delusions, hallucinations, or formal thought disorder before treatment. The second estimate was the duration (in years) of behavioral change, assessed as the duration of any significant changes in school or work performance, social relationships, or personal habits.

Estimates of the duration of untreated psychosis and of behavioral change were reached by consensus of a research psychiatrist and trained research assistant after they independently reviewed all records. The mean duration of untreated psychosis was 11.4 months (SD=16.2, range=<1–72), and the mean duration of behavioral change was 3.4 years (SD=6.1, range=<1–41).

All subjects were assessed within a month of hospitalization and after stabilization with a conventional neuroleptic medication. However, eight subjects did not complete the full neuropsychological battery at that time, and 10 patients had incomplete MRI scans (missing measurements of the frontal and occipital poles of the cerebral hemispheres and of a portion of the cerebellum for seven patients, and missing temporal lobe measurements for three patients). Therefore, these subjects were eliminated from analyses that included those variables.

Before performing correlational analyses, the raw MRI volumes were converted to Z scores on the basis of the mean and standard deviation from the group of 20 comparison subjects measured at the same time by the same investigator

(42). Multiple regression analysis was used to regress the Z scores on subjects’ height to account for variance in body size that would contribute to differences in size of brain structures. The residuals were then correlated with the duration of untreated psychosis and the duration of behavioral change by using Spearman rank-order correlations. The MRI variables were left and right hemispheric volumes, left and right temporal lobe volumes, and left and right lateral ventricular volumes. Additional details about the methods used to produce the MRI measurements are provided by DeLisi and colleagues

(44,

45).

In addition, Spearman rank-order correlations were computed by using the baseline scores on the neuropsychological summary scales measuring deficits in language, executive, verbal memory, spatial memory, concentration/speed, and sensory/perceptual abilities. Scores on the neuropsychological summary scales were normalized by calculating Z scores on the basis of scores from a battery of standardized tests for each category

(24,

30,

44). Spearman rank-order correlation was chosen for the analyses because preliminary univariate analyses showed that many of the variables were not normally distributed.

The duration of untreated psychosis was also treated as a dichotomous variable, with 1 year as the cutoff point. Patients were divided into two groups: those with <1 year of untreated psychosis (N=15) and those with >1 year of untreated psychosis (N=35). For the brain structure variables, analyses of covariance with height as covariate were performed to test for differences between the two groups. For the neuropsychological summary measures, independent t tests were used to test for differences.

Results

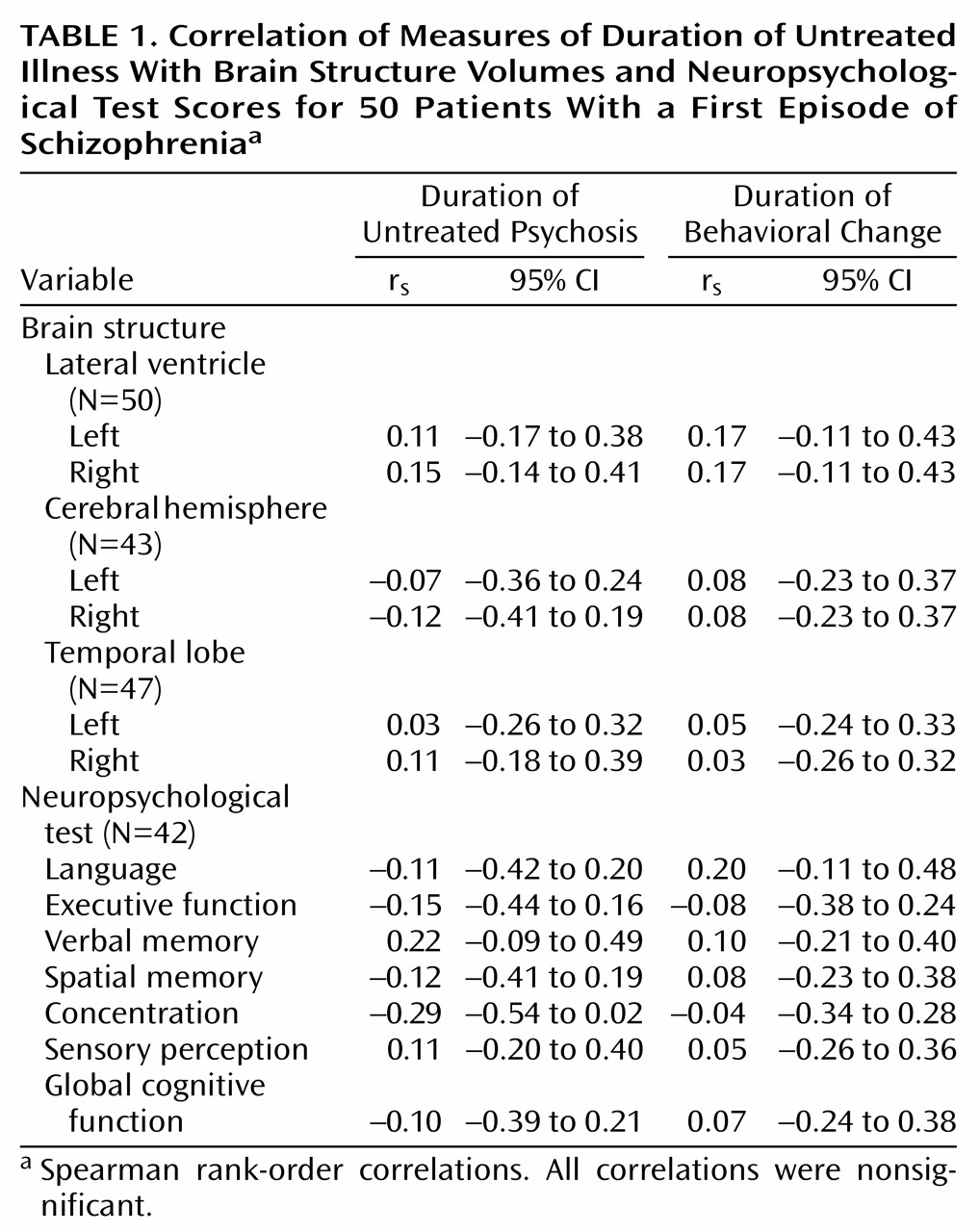

No statistically significant correlations were found between either measure of duration of untreated illness and baseline brain structure volumetric measurements. There were also no significant relationships between the measures of duration of untreated illness and the neuropsychological summary scores (

Table 1).

In addition, separate analyses by sex did not reveal any significant relationships, although the female subjects had a significantly longer mean duration of untreated psychosis than the male subjects (mean=18.7 months, SD=22.1, compared with mean=7.3 months, SD=9.9) (t=2.5, df=48, p<0.01).

No statistically significant differences were found between patients with <1 year and >1 year of untreated psychosis on either the brain structure variables or the neuropsychological test variables.

Discussion

The analysis failed to provide evidence for a relationship between duration of untreated illness and the severity of cognitive deficits or structural brain anomalies in subjects with schizophrenia during their first episode of illness. Although some researchers have implied that delayed treatment in a potential first episode of schizophrenia allows brain damage to accumulate

(5,

6), no study has yet yielded direct evidence that this has occurred. Most reports have shown a significant correlation of duration of untreated illness and outcome, such that the longer the untreated illness, the poorer the outcome

(7,

8,

10–

12,

46). Waddington and colleagues

(47) found that the severity of negative symptoms, perhaps reflective of an underlying neurodegenerative process, was correlated with duration of untreated illness. Another study provided evidence for an association between the level of general cognitive impairment, although not of executive dyscontrol, and duration of untreated psychosis

(48). However, in these two reports, the subjects had been ill for many years and had been treated for their illness by the time of assessment; thus the observed correlations could be influenced by events that occurred after the initiation of treatment. In the study reported here, all patients were examined at the time of their first psychotic episode. Thus, indicators of cognitive or neurobiological deficit could not be the result of any process occurring as a result of treatment and chronicity in general.

Our results were similar to those of Loebel et al.

(10), who found that the average duration of untreated psychosis was approximately 1 year and the average time between onset of behavioral change (prodromal symptoms) and treatment was approximately 3 years. Our corresponding averages were 11.4 months (SD=16.2) for duration of untreated psychosis and 3.4 years (SD=6.1) for duration of behavioral changes. However, unlike Loebel et al.

(10) and Larsen et al.

(11), we did not find that duration of untreated illness was substantially longer for male patients than for female patients. It is unclear what might account for the longer period of untreated psychosis for the female patients in our study. However, several other studies have not found a longer period of untreated illness in male patients than in female patients

(49–

51).

A recent epidemiological survey conducted in the same geographical region as our study failed to find an association between duration of untreated illness and 24-month illness outcome

(52). Another independent study of neuroleptic-naive patients with DSM-IV schizophrenia showed no relationship between untreated illness duration and quality of life, symptom severity, or remission 6 months after the patients’ initial hospitalization

(51). Nevertheless, much of the literature does support the idea that untreated psychosis may be associated with worse clinical outcomes. Since we do not report data on clinical outcome, we cannot comment on these findings. It may be that brain structural pathology and cognitive deficits at the first episode are predictive of outcome. However, our data suggest that poorer clinical outcomes cannot be attributed to the effects of duration of untreated psychosis on cognition functioning or on brain structural variables.

One possible explanation for our negative results is that the small size of the study group did not afford sufficient power to detect statistically significant correlations. As

Table 1 shows, most correlations were close to 0 and all 95% confidence intervals included estimates of 0. Our study group did provide 80% power to detect a correlation of 0.40 or higher. Nonetheless, it is possible that a larger study group size with greater power could detect statistically significant correlations.

The present study thus provides no support for the hypothesis that a period of untreated illness is toxic to brain structure or function. However, this retrospective analysis will need support from longitudinal prospective studies of high-risk individuals. In addition, studies that involve larger numbers of patients, which would permit the analysis of data on subgroups of subjects with particular clinical presentations, and studies that use more detailed methods for brain structure analysis could yield results to support this hypothesis.