Risk-Benefit Decision Making for Treatment of Depression During Pregnancy

Abstract

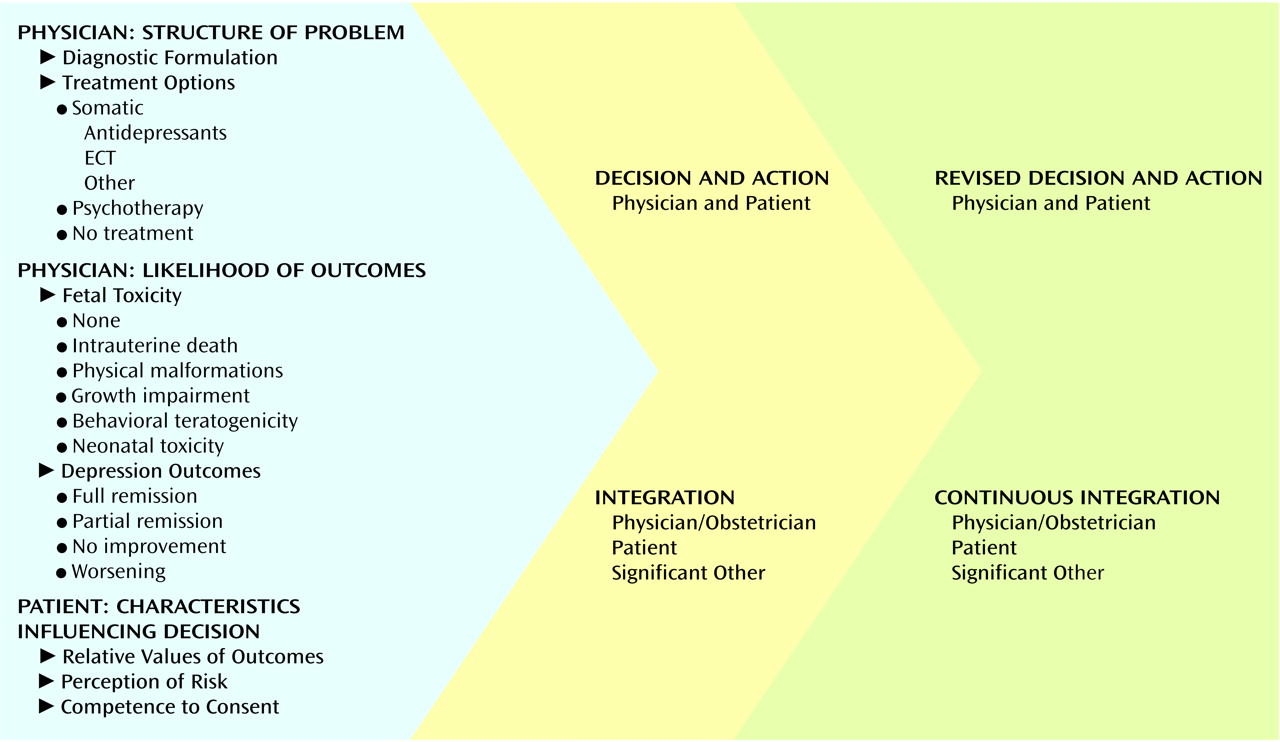

Model for Clinical Decision Making During Pregnancy

Physician: Structure of Problem

Diagnostic Formulation

Treatment Options

Somatic therapy

Psychotherapy

No treatment

Physician: Likelihood of Outcomes

Fetal Toxicity

Intrauterine death

Physical malformations

Growth impairment

Behavioral teratogenicity

Neonatal toxicity

Depression Outcomes

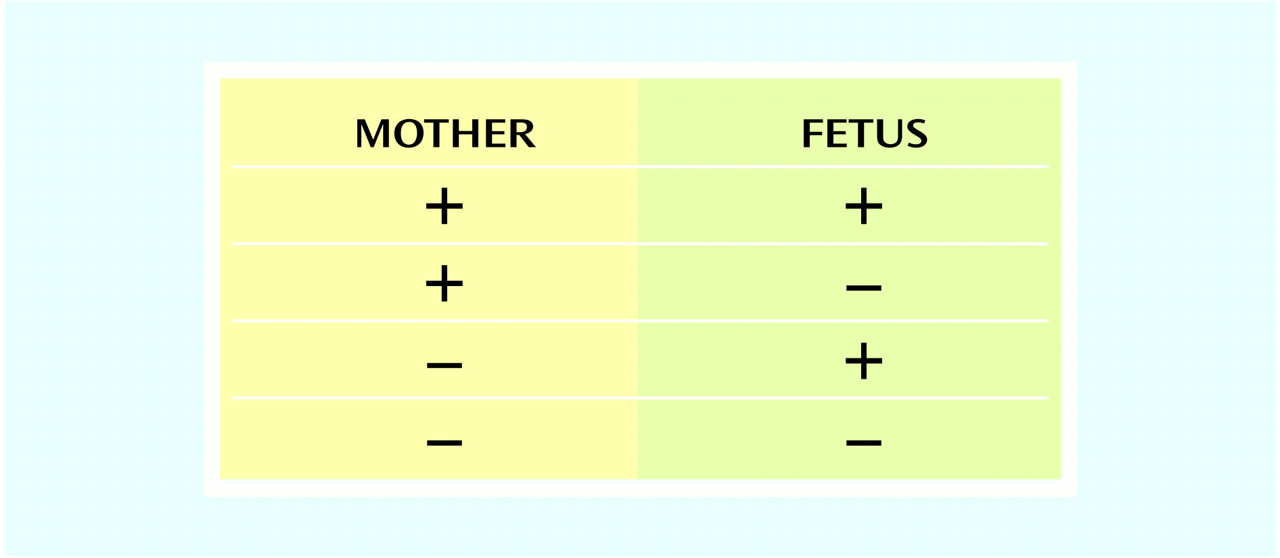

Patient: Characteristics Influencing Decision

Relative Values of Outcomes

Perception of Risk

Competence to Consent

Decision and Action

Case 1

Ms. A was a 28-year-old married woman. She sought psychiatric evaluation for severe insomnia, depressed mood, panic attacks, and a 10-lb weight loss over 3 weeks. She did not smoke or use alcohol. Her psychiatrist recommended treatment with the antidepressant nortriptyline. A few days later, Ms. A was pleased to learn she was pregnant. Her psychiatrist told her by telephone to stop taking the nortriptyline because it was “not safe to use in pregnancy.” She was given no further advice. When her symptoms increased, she was enrolled in a group education program for expectant mothers. A few weeks later, her symptoms were intolerable. She saw her obstetrician, who also advised her not to take antidepressant medication because he believed that the symptoms would remit after the first trimester of pregnancy. When the symptoms intensified, her obstetrician recommended that she seek additional mental health consultation. Ms. A’s psychiatrist refused to treat her with medication unless she signed a form that he described as a statement that neither he nor the organization would be responsible if any harm came to the fetus. He did not provide a risk-benefit discussion. Ms. A was distressed by the psychiatrist’s approach. At her husband’s urging, Ms. A sought evaluation and treatment from a psychiatrist outside her insurance network.The consulting physician met with Ms. A and her husband. They were given oral and written information about the diagnosis, major depression (43), which was in the severe range. Her score on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (44) was 31. The treatment options for depression were described as in Figure 1. Somatic treatments (antidepressant medication and ECT) and/or cognitive behavior therapy were offered to Ms. A. The risks of a continued lack of treatment for depression were reviewed: poor nutritional intake during pregnancy and severe fatigue and anxiety (with intermittent panic attacks) that disrupted her physical, social, and occupational functioning.For each treatment option, there is a lower or higher probability of fetal toxicity within each domain in Figure 1. There are also four possible outcomes for the depressive episode: remission, improvement, continuation at the same symptom level, or worsening. The consulting psychiatrist explained that several prospective studies provided data about antidepressant exposure during pregnancy. Fluoxetine has been studied as a single agent, and tricyclic antidepressants have been studied as a group, as have the SSRIs sertraline, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine. The information specific to the likelihood of each reproductive toxicity domain (discussed earlier in this article and extensively in our review [5]) was given to Ms. A and her husband. The consultant, Ms. A, and her husband believed that the probability of depression remission would be greatest with somatic treatment, because of the severity of the symptoms. When all treatment options and consequences were presented, Ms. A’s valuations of different outcomes were considered. After discussion with Mr. A, Ms. A’s sister (a physician), and her obstetrician, Ms. A decided that antidepressant medication was most acceptable to her. Her obstetrician supported the decision. In a telephone call initiated by the consultant psychiatrist, the obstetrician expressed his interest in understanding the distinction between first-trimester discomforts, which subside, and major depression.Ms. A selected nortriptyline treatment. After several weeks she experienced complete remission of symptoms, which continued throughout the pregnancy. The anticipated outcome that justified exposure to medication (remission of depression) had occurred. She delivered a healthy baby at term, with no neonatal complications. She remained in full remission during the first postpartum year, and nortriptyline was tapered successfully.Ms. A described her depression as intolerable, and the option of no treatment was not acceptable because of the high probability that the depression would not remit. Since the depression was associated with serious weight loss and poor nutrition, her obstetrician became concerned. Ms. A did not believe that psychotherapy would be as likely to be effective, because she had difficulty concentrating. Therefore, she considered antidepressants and ECT, which were expected to be successful in treating her depression. Given these options, she chose nortriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, for several reasons. She was already familiar with the treatment and had had no side effects from her brief exposure, a relative had responded well to the drug, and she was reassured by the fact that nortriptyline has been used to treat depression for several decades.

Case 2

Ms. B was a 34-year-old married woman. At week 19 of gestation, she was referred for consultation by her psychiatrist and therapist because she refused to take medication during pregnancy. She previously had a good response to fluoxetine and was being treated with weekly interpersonal psychotherapy. Her treatment team was concerned that she was becoming increasingly debilitated by her severe depression. She was unable to function at her managerial position and took a leave of absence.Upon examination by the consultant psychiatrist, Ms. B was tearful and agitated. Her score on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (44) was 28 (severe range). She had depressed mood and anxiety, sleep disturbance with only 2–4 hours of sleep per night, and a weight gain of only 5 lb. She had suicidal ideation but no active plan. She tearfully revealed the story of her previous stillbirth at week 24 of gestation. She noted that her distress was increasing as the gestational week of the previous stillbirth approached. The psychiatrist presented the structure of the consultation and decision-making process to Ms. B alone, since her husband was not willing to attend. She was knowledgeable about her diagnosis of major depression. The treatment options were described as in Figure 1. The risks of fetal toxicity in the five domains were reviewed. The likelihood of the depression continuing was high because of Ms. B’s history of chronic depression without pharmacologic treatment. The likelihood that the depression would remit would be greatest for the somatic treatment options (such as fluoxetine, to which she had previously responded), but the possibility of a less optimal fetal outcome was not tolerable for Ms. B. Once all treatment options and their consequences were presented, Ms. B’s valuations of the different outcomes were considered. Her obstetrician encouraged her to select a somatic treatment.Ms. B stated that she could not accept medication or ECT. She said that she would not be able to tolerate the thought that she might have played a role in harming her baby if there was a negative outcome. Ms. B clearly stated that she understood the benefits and risks of treatment. She was pleased about her previous response to fluoxetine. She was aware that the untreated depression was posing a risk to her health and to the health of the fetus. She chose to continue weekly psychotherapy with monitoring for symptom level and suicidality, but she did not improve. She also tried morning bright light therapy but experienced no response. Unfortunately, she experienced a second stillbirth at 24 weeks’ gestation. She accepted fluoxetine treatment and continued psychotherapy after the stillbirth and eventually recovered from her depression.Ms. B felt that any treatment option that increased the risk to the fetus was not acceptable. She dreaded another fetal demise. She viewed taking medication as an active choice that carried risk for which she was responsible. The effects of her illness on herself and the fetus were viewed as “in God’s hands.” Her thoughtful responses within the context of the risk-benefit discussion provided evidence of competence to decide about medical care on her own behalf. There was no legal or ethical way to force Ms. B to accept somatic therapy under these circumstances, which were driven by the values she brought to the decision-making process.

Conclusions

Footnote

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBGet Access

Login options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).