The validity of the borderline personality disorder construct in young patients has been a topic of debate

(1,

2). Previous data, primarily obtained from community samples

(3,

4) and our own Yale Psychiatric Institute Adolescent Follow-Up Study of a clinical study group

(5–

7), have suggested that personality disorders in adolescents can be reliably diagnosed, occur frequently, and have concurrent validity (i.e., they are valid indicators of distress and dysfunction) but that they have only modest predictive validity and that they are relatively unstable over time. We have also examined the validity of the personality disorder construct in hospitalized adolescents by evaluating the cohesiveness (internal consistency) of the personality disorder criteria, as well as criterion overlap

(8). When we compared our results to those of an analogous group of adult inpatients, we found that the personality disorder criteria, when used with adolescents, tended to have lower internal consistency and less discriminant validity. Taken together, these studies suggest that the symptoms of personality disorders in adolescents may indeed accurately reflect current distress and dysfunction but that they may not represent coherent, differentiable syndromes with stability over time.

Despite the frequent use of the borderline personality disorder diagnosis in clinical practice, there are relatively few studies in adolescents of this diagnosis specifically. Some studies have focused on developmental histories of abuse, neglect, and early separation

(9,

10) and on disturbed object relations in adolescent patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder

(11), although none of these has used the DSM criteria in defining borderline personality disorder. More recently, investigators have used the DSM-III-R criteria to demonstrate some degree of concurrent validity

(12)—but low diagnostic stability

(13,

14)—for borderline personality disorder in adolescent patients. However, only one of these reports

(13), employing a subset of the data from the Yale Psychiatric Institute Adolescent Follow-Up Study, made use of a semistructured interview for DSM-III-R diagnoses in defining borderline personality disorder.

The construct validity of personality disorder diagnoses, as well as issues related to the underlying nature of these disorders, can also be approached by means of the study of comorbidity. Although several studies have examined the co-occurrence between personality disorders, or borderline personality disorder specifically, and various axis I disorders in adults

(15–

19), few have done so using adolescent subjects. Studies that have been carried out among adolescents have tended to examine the frequency of the occurrence of the personality disorders in patients with specific axis I disorders, such as incarcerated juveniles with conduct disorder

(20) or adolescents with bipolar disorder

(21). Our studies of co-occurrence patterns for various axis I disorders in adolescent inpatients have demonstrated significant comorbidity for borderline personality disorder with substance use disorders and depression, although not with disruptive behavior disorders

(22–

26). By comparison, when we examined the patterns of the co-occurrence of borderline personality disorder with axis I disorders in an analogous group of adult inpatients, we found significant comorbidity of borderline personality disorder with only eating disorders and substance use disorders

(22).

Perhaps more valuable to evaluating the validity of the borderline personality disorder construct, however, given the demonstrated overlap between disorders on axis II

(27,

28), is an examination of comorbidity patterns with other personality disorders. Again, several studies have been conducted in adults. Oldham and colleagues

(29) used a sample of 100 severely ill patients and two different structured interviews for the DSM-III-R personality disorders to examine co-occurrence patterns within the axis II disorders and found a broad pattern of statistically significant comorbidity with borderline personality disorder—and indications of especially strong covariation with histrionic personality disorder. Stuart and co-workers

(30) employed a much larger clinical study group and a structured interview for DSM-III-R personality disorders to examine axis II co-occurrence patterns and found borderline personality disorder correlating significantly with all other cluster B disorders and dependent personality disorder. Relatively few studies have used the DSM-III-R criteria to examine the comorbidity of borderline personality disorder specifically with other personality disorders in adults. Although they did not use a structured research interview, Nurnberg and colleagues

(31) examined the comorbidity of borderline personality disorder with other axis II disorders in 110 outpatients and found broad diagnostic overlap that spanned all three personality disorder clusters. Zanarini and co-workers

(32) used a structured interview in a sample of 504 inpatients with personality disorders. Compared to subjects without borderline personality disorder, subjects with borderline personality disorder had significantly higher rates of paranoid, avoidant, and dependent personality disorders.

Similar studies of the comorbidity of borderline personality disorder with other personality disorders have not been performed in adolescents—to our knowledge. Especially given the indications that there may be more of an overlap of the personality disorder criteria in adolescents than in adults

(8), the results of such investigations may contribute to our understanding of the borderline personality disorder construct in this age group. The purpose of this study was to explore further the validity of the borderline personality disorder construct in adolescents, and the nature of the syndrome in this population, by examining DSM-III-R axis II comorbidity in a group of consecutively admitted adolescent inpatients who had been reliably assessed with structured diagnostic interviews. For comparison, we performed the same analysis on a group of consecutively admitted adult inpatients who were subjected to identical axis II assessment procedures.

Method

Subjects

Our subjects were 138 adolescents who were consecutively admitted to the Yale Psychiatric Institute, a private, nonprofit, tertiary-care psychiatric facility. Patients were admitted because of their clinical need for inpatient-level psychiatric treatment; there were no other selection criteria. This consecutive series was drawn from a larger nonconsecutive series of 165 inpatients, representing nearly all of the adolescent admissions to the hospital between 1986 and 1990. A detailed description of this heterogeneous group is given elsewhere

(7). To facilitate statistical analysis, only the consecutive series was used for this comorbidity study.

Of the 138 subjects, 76 (55%) were male, and 62 (45%) were female. They ranged in age from 12 to 18 years (mean=15.5, SD=1.4). With regard to ethnicity, 114 (83%) subjects were Caucasian, 11 (8%) were African American, six (4%) were Asian American, and seven (5%) were of other backgrounds. The subjects were predominantly of middle-class socioeconomic status; 70% were families in Hollingshead-Redlich social classes I–III

(33). At admission, the group had a mean rating on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (DSM-III-R) of 38.1 (SD=7.6).

A series of 117 adult subjects, consecutively admitted to the same hospital during the same period, was used for comparison. The group consisted of 61 (52%) males and 56 (48%) females, with a mean age of 23.6 years (SD=5.6). Again, most (97%) of the adults were Caucasian, and most were of middle-class socioeconomic status. The group’s mean rating on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale at admission was 34.2 (SD=10.6).

After the subjects received a complete explanation of the study procedures and before we initiated the interviews, written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. In the case of minors, assent was obtained from the subjects, and consent was obtained from their parents or guardians.

Procedures

All subjects received a systematic diagnostic evaluation, including administration of the Personality Disorder Examination

(34), a semistructured diagnostic interview that assesses the presence of all 11 recognized DSM-III-R personality disorders. In adult subjects, traits must be pervasive and persistent for a minimum of 5 years. In adolescent subjects, a trait is considered present if it has been pervasive and has persisted for at least 3 years

(34). Antisocial personality disorder was not diagnosed in the adolescent group because of the age criterion.

Interviews were conducted by a trained and monitored research evaluation team that functioned independently of the clinical team and was blind to the study aims. Interrater reliability of Personality Disorder Examination diagnoses was assessed by independent simultaneous ratings by pairs of raters of 26 subjects from the overall study group; kappa coefficients ranged from 0.65 for paranoid personality disorder to 1.0 for histrionic, avoidant, and passive-aggressive personality disorders (mean kappa=0.84, SD=0.14). Final research diagnoses were assigned at an evaluation conference attended by the research evaluation team only, approximately 4 weeks after admission. These diagnoses were established by the best-estimate method on the basis of structured interviews and any additional relevant data from the clinical record, following the LEAD (longitudinal, expert, all data) standard

(35,

36).

To determine significant patterns of diagnostic co-occurrence, subjects with borderline personality disorder were compared to subjects without borderline personality disorder. Specifically, rates of occurrence of other personality disorders were calculated for the groups with and without borderline personality disorder. When expressed as a decimal fraction, the former is the conditional probability of having the other personality disorder, given the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, and can also be termed the sensitivity or the true positive rate. The latter is the conditional probability of having the other personality disorder, given the absence of borderline personality disorder, and can also be expressed as one minus the specificity, or the false positive rate. The differences between these two rates were analyzed by means of chi-square tests, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. This conservative approach defined significant co-occurrence as greater than that observed in a relevant comparison group that was ascertained similarly and obtained from the same overall study group

(37). Also, to allow for future meta-analysis, we calculated odds ratios whenever possible. Separate analyses were conducted for adolescents and adults, and the results were compared.

Results

Among the adolescents, 68 (49%) of the subjects met the diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder, and 70 (51%) did not. When these groups were compared with respect to sociodemographic and severity variables, no significant differences were found for age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, age at first psychiatric contact, age at first psychiatric hospitalization, or number of prior hospitalizations. There were significant differences between the groups for gender: the group with borderline personality disorder had a significantly greater proportion of female subjects (56%, N=38, versus 34%, N=24) than the group without (χ2=6.50, df=1, p<0.01, two-tailed), and the group with borderline personality disorder had a lower mean current rating on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (36.7, SD=6.9, versus 39.6, SD=8.0) than the group without (F=2.13, df=1, 119, p<0.05, two-tailed).

Among the adults, 50 (43%) of the subjects met the criteria for borderline personality disorder, and 67 (57%) did not. These groups did not differ significantly on sociodemographic or severity variables, except the group with borderline personality disorder had a lower mean age at first psychiatric contact (15.6 years, SD=5.6, versus 18.5 years, SD=6.9) than the group without (F=2.42, df=1, 105, p<0.05, two-tailed).

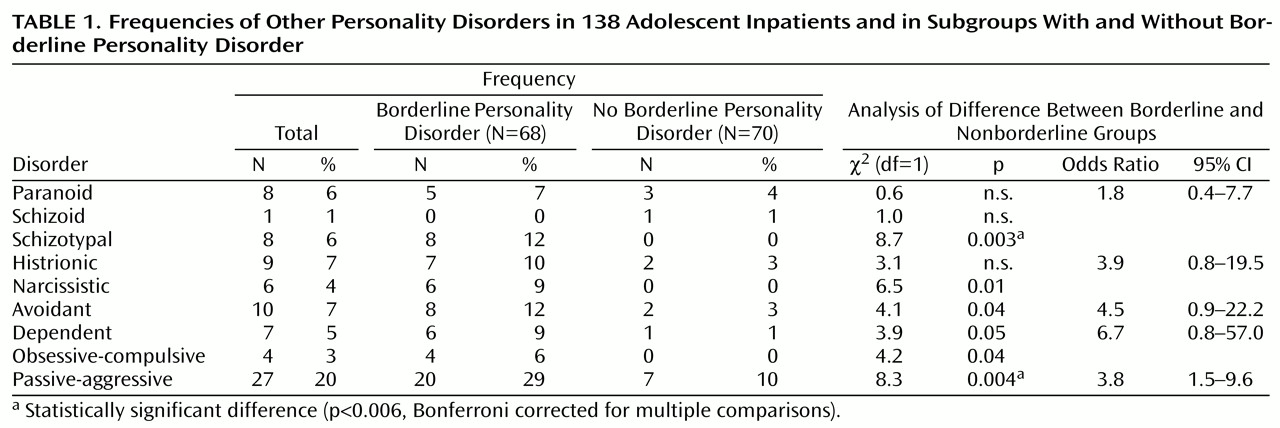

Table 1 shows the frequencies of each of the other personality disorders in the adolescent subgroups with and without borderline personality disorder and the results of the analyses. None of the other personality disorders approached the frequency of borderline personality disorder; the next most frequent diagnosis was passive-aggressive personality disorder, which occurred in 20% of the subjects. With the exception of schizoid personality disorder, which occurred in only one subject, all the disorders occurred at higher rates in the group with borderline personality disorder than in the group without (i.e., true positive rates are higher than false positive rates). We determined from chi-square analysis at the Bonferroni-corrected alpha level of p<0.006 that borderline personality disorder showed significant co-occurrence with schizotypal and passive-aggressive personality disorders.

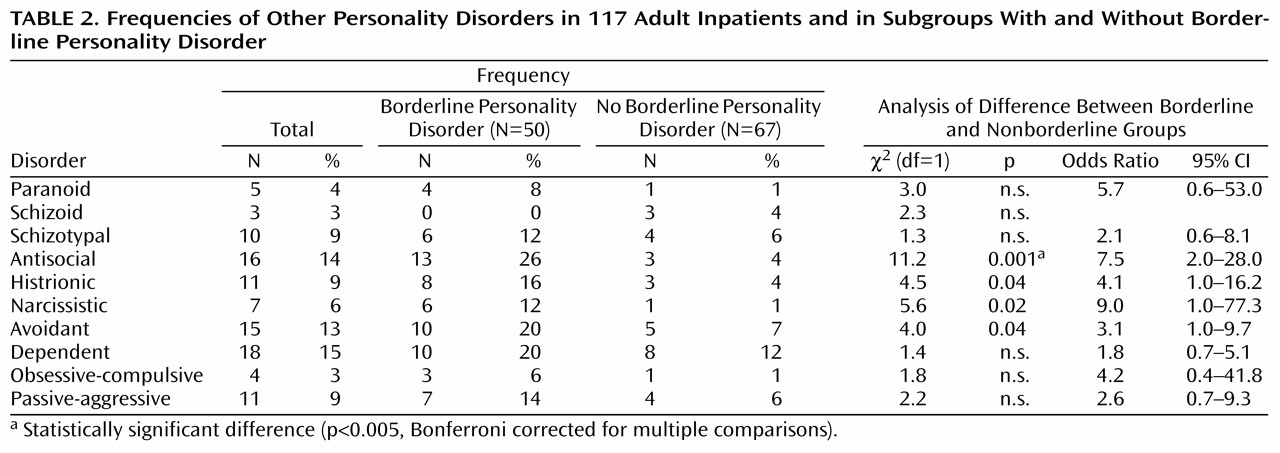

Table 2 shows the frequencies of each of the other personality disorders in the adult subgroups with and without borderline personality disorder and the results of the analyses. Again, none of the other personality disorders approached the frequency of borderline personality disorder. Also, with the exception of schizoid personality disorder, all the disorders occurred at higher rates in the group with borderline personality disorder (again, true positive rates are higher than false positive rates). We determined from chi-square analysis at the Bonferroni-corrected alpha level of p<0.005 that borderline personality disorder showed significant co-occurrence with only antisocial personality disorder.

Discussion

Our study, in which we examined the comorbidity of other personality disorders with borderline personality disorder in comparable groups of adult and adolescent inpatients with the use of diagnostic data obtained with reliably administered, structured diagnostic interviews, contributes to the growing literature on the nature and validity of the borderline personality disorder diagnosis in adolescents. We found evidence of fairly broad borderline personality disorder comorbidity in the adolescent group, encompassing aspects of clusters A and C. After we performed Bonferroni-corrected chi-square analysis, borderline personality disorder showed statistically significant co-occurrence with schizotypal and passive-aggressive personality disorders. In the adult group, by contrast, we found a comorbidity pattern that was less broad and more concentrated on cluster B. Bonferroni-corrected chi-square analysis revealed statistically significant comorbidity with borderline personality disorder for only antisocial personality disorder.

Our findings regarding adults are consistent with those of Stuart and colleagues

(30), which indicated primarily an association between borderline personality disorder and other cluster B disorders, but they contrast with those of two other studies that also employed semistructured research interviews

(29,

32). Oldham and co-workers

(29) and Zanarini et al.

(32) reported broader patterns of the comorbidity of other axis II disorders with borderline personality disorder. The study by Nurnberg and colleagues

(31), which did not make use of a semistructured research interview, also demonstrated a broad pattern of comorbidity with borderline personality disorder, not limited to the other cluster B disorders. The differences in the results from these various studies of axis II comorbidity with borderline personality disorder in adults are possibly due to methodological differences and varying base rates of the personality disorders.

Our results regarding the diagnostic comorbidity of borderline personality disorder with other axis II disorders in adolescents are consistent with our previous findings concerning the personality disorder criteria

(8). Our study of internal consistency and criterion overlap demonstrated a tendency for the criteria of different personality disorders to overlap more with each other in adolescents than in adults. For adults, we found the best intercorrelation between the criteria of borderline personality disorder and the criteria of other cluster B disorders. For adolescents, the criteria of borderline personality disorder correlated best with the criteria of a broad range of personality disorders spanning all three clusters. These convergent findings suggest that the construct of borderline personality disorder may represent a more diffuse range of psychopathology in adolescents than in adults.

It should be noted that our adolescent and adult groups were both consecutive series of patients admitted to similar levels of care within the same hospital and that they were subjected to identical axis II diagnostic protocols by the same evaluation team at the same stage of treatment. Our methods, therefore, tended to reduce sampling and selection confounds

(38) and allowed for a meaningful comparison between the groups. Moreover, the differences that we observed between the groups were not likely attributable to differences in the base rates of the personality disorders. As reported elsewhere by Grilo and colleagues

(39), the rates of personality disorders were largely similar across these two age cohorts; the only significant differences were a higher frequency of passive-aggressive personality disorder and a lower frequency of dependent personality disorder in the adolescents than in the adults. The differences that we observed between the groups were also not likely attributable to differences in axis I comorbidity patterns. As noted earlier, our previous report of the co-occurrence of axis I disorders with borderline personality disorder revealed few differences between age cohorts; the adolescent group had significant comorbidity of borderline personality disorder with depression and substance use disorders, and the adult group had significant comorbidity of borderline personality disorder with eating disorders and substance use disorders. Finally, our use of a conservative duration criterion

(34), more stringent than that required by either DSM-III-R or DSM-IV, was likely to have minimized trait-state artifacts

(40), which suggests that our results were not simply reflective of the effects of acute axis I pathology.

Our study has several limitations. First, from the standpoint of applicability to current practice, we used the DSM-III-R personality disorder criteria and diagnostic categories. Although many items were modified slightly for the new manual, there were few changes overall. These included the addition of one item for borderline personality disorder, several modifications to the criteria for antisocial personality disorder, and the removal of passive-aggressive personality disorder from the classification to an appendix for further study (DSM-IV). Second, we relied on just one structured diagnostic interview, the Personality Disorder Examination. Given the modest convergence between this instrument and, for example, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (axis II)

(29,

41), our results may have been different had we made use of an alternative diagnostic interview. Third, our inpatient subjects were representative of severely ill populations with high levels of diagnostic comorbidity, and our results, therefore, may not be generalizable to outpatient or community settings. None of these limitations, however, would account for the differences that we found between adults and adolescents. Finally, our assessments here were cross-sectional. Although these results may inform our understanding of the nature and construct validity of the borderline personality disorder diagnosis at a given point in adolescence, longitudinal studies are needed to understand the evolution of this disorder in individuals over time and the ways in which the development of these symptoms may interact with normal and pathological developmental processes.

Despite these limitations, several conclusions can be drawn from these data. We found a broad pattern of diagnostic overlap between borderline personality disorder and the other personality disorders in adolescents, which stands in contrast to the relatively narrow pattern of overlap that we observed in adults. This finding suggests that borderline personality disorder encompasses a more diffuse range of psychopathology in adolescents. Although our observations do, for example, tend to support the validity of the cluster B construct in adults, we did not find support for the construct validity of either borderline personality disorder or cluster B in adolescents. Taken together with other studies that have evaluated the construct validity of personality disorders and the borderline personality disorder diagnosis in adolescents

(3–

8,

12–

14), these results suggest that borderline personality disorder is a frequently diagnosed disorder that may have concurrent validity in adolescents—insofar as it is a valid indicator of distress and dysfunction—but that it may not represent a stable, coherent, or differentiable syndrome within this age group.

Indications of the relatively low stability and predictive validity of diagnoses

(3,

4,

6,

7) and the diminished internal consistency and discriminant validity of criterion sets

(8) suggest that the symptoms of personality disorders, including those of borderline personality disorder, should be interpreted differently in adolescents than in adults. It is quite possible that symptom sets other than those currently offered in DSM may have improved construct validity in this young patient population. The current criteria have been developed primarily for application to adults. Despite the phenomenologic similarities of personality disorders in adults and adolescents, it is unlikely that these disorders would have identical symptomatic features in the two age groups

(6,

42). It is possible that dimensional approaches to classification and assessment may improve our ability to understand the nature of normal and abnormal personality development during adolescence. Such approaches to personality pathology have been suggested elsewhere

(43) and have proven useful to our understanding of other aspects of adolescent psychopathology

(44). It is hoped that future studies will involve longitudinal designs to help us better understand the developmental progression of these symptoms and syndromes and that such studies will also evaluate the potential benefits of dimensional approaches to personality pathology in this age group.