Surveys suggest that as many as one-half of all psychiatrists lose a patient to suicide; about one-third of those endure the loss during their residency training

(1–

3). Studies find that clinicians and surviving family members and friends react similarly to such losses, experiencing shock, grief, guilt, and anger

(4,

5). Clinicians also feel the particular anguish of a therapist losing a patient

(4,

6,

7), which many describe as the most profoundly disturbing event of their professional careers.

We have been collecting information for more than 10 years from psychotherapists who experienced the suicide of a patient they were treating. Our primary goal was to learn about suicide from a relatively untapped source of information, but therapists also made plain their wish to discuss their emotional responses to the suicides. As a result, we expanded our study to consider the therapists’ experiences and to integrate them with the detailed information we collected about the patients, the therapy, and the patient-therapist relationships.

Method

The findings presented in this article are based on the reactions of the therapists in each of the 26 suicides studied to date. One therapist contributed two suicide cases, but in this analysis each case has been treated separately.

Therapists learned of the Suicide Data Bank project from colleagues, notices in psychiatric publications, mailings from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, or the relatives of patients who died by means of suicide. For a patient to be included in the Suicide Data Bank, the therapists had to complete a comprehensive 15–20-page narrative description of the case, demographic and psychodynamic questionnaires, and a semistructured questionnaire eliciting the therapists’ reactions. Each therapist discussed his or her case—and his or her reactions—at an all-day workshop in which three therapists reviewed their cases with the three project psychiatrists (H.H., A.L. and J.T.M).

All cases were actual patients who committed suicide, who saw the therapist for at least six visits, and who had some contact with the therapist during the 2 months before death. Treatments for these 26 patients lasted from 3 weeks to 48 months, with a median of 12 months. Twenty-four patients were seen on a regular basis: 13 were seen two or more times a week, 11, once a week, and two were seen less regularly.

In 11 cases, the suicides occurred less than 2 years before the therapist’s participation in this project; an additional 12 occurred between 2 and 5 years earlier. For the three cases seen many years earlier, the therapists’ detailed treatment records fulfilled the project’s requirements.

Twenty-one of the participating therapists were male, and five were female. Twenty-one were psychiatrists, four were psychologists, and one was a psychiatric social worker. Eleven were in practice more than 10 years, eight had 5–10 years’ experience, and seven were in training at the time of their patients’ suicides.

We initially wondered if the therapists could be frank in discussing what most of them regard as treatment failures. However, the participating therapists proved eager to reveal all they could to learn from the experience, and they welcomed the opportunity to present their cases to others with comparable experiences. Virtually all felt their participation was therapeutic as well as educational.

Results

Emotional Reactions

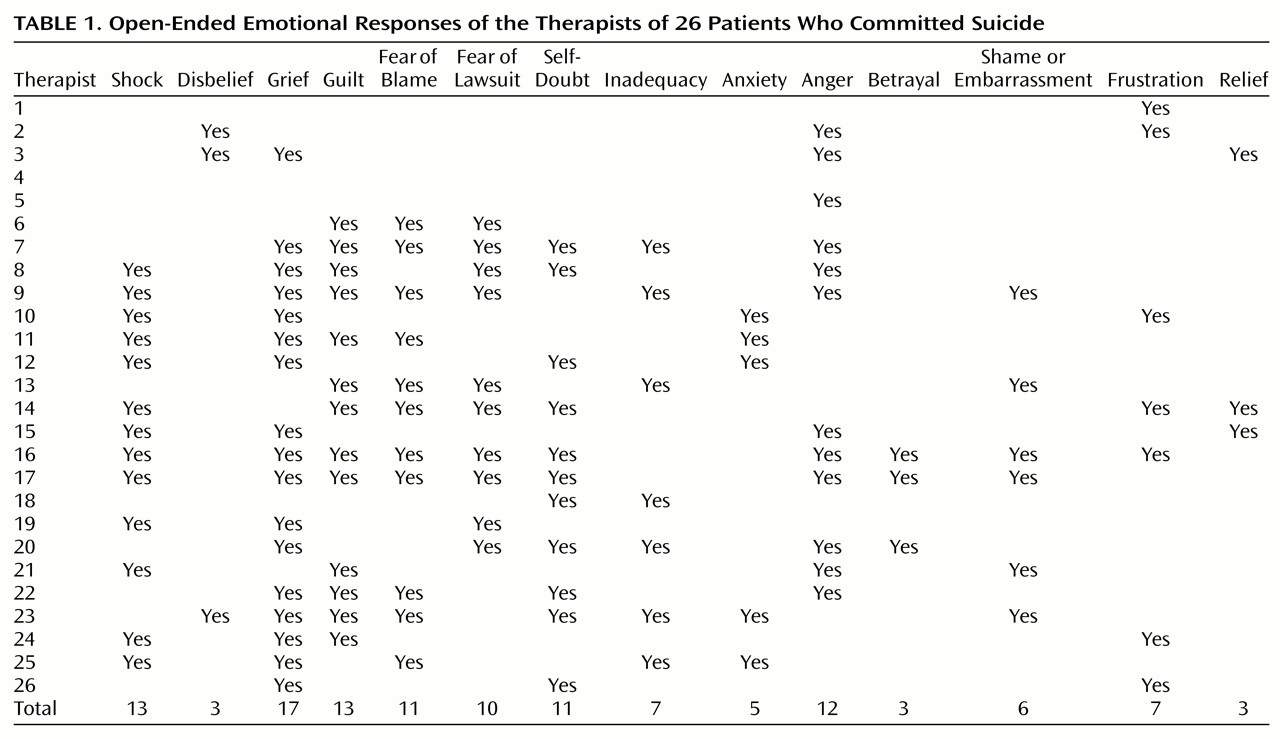

An open-ended, unscaled question on the therapists’ questionnaire asked them to describe their emotional reactions to their patients’ suicides; their responses are listed in

Table 1. These responses were generally consistent with the ratings they provided on a later section of the questionnaire that asked them to rank on a 4-point intensity scale (“absent,” “minimal,” “moderate,” or “severe”) the strength of some specified emotions: grief, anger, guilt, and fear of blame. Thirteen therapists experienced these emotions in gripping dreams or fantasies; 10 could still recall these vividly.

Shock or Disbelief

On the initial open-ended question, 13 of the therapists reported that they were shocked to learn of the patient’s suicide; three others described their reaction as disbelief, which appeared to be a milder form of shock. Six of the therapists who reacted with shock and one who reacted with disbelief were not aware that their patients were acutely suicidal. Some of these six therapists experienced an extreme level of shock; one developed what he described as a posttraumatic stress syndrome after the surprising suicide of his patient, a young man with schizophrenia who was responding well to clozapine and who never threatened or attempted suicide in his 4 years of treatment. The therapist recalled that for the next 2 years, “Every time the phone rang in the middle of the night, I would be fearful that it was bad news concerning suicide.”

Seven therapists who reported feeling shock and two who reported feeling disbelief were aware that their patients were in a suicide crisis. Their reactions may be roughly compared to that of combat soldiers who, although they are aware of the danger of imminent injury or death, do not believe it will happen to them and are shocked when they are wounded or someone close to them is killed.

Grief

Once past the initial reaction to the suicide, the most frequent emotional response reported by therapists was a sense of grief (17 therapists on the open-ended question and 18 on the scaled question). For some, this feeling was pervasive and long-lasting, as described by this therapist.

My primary emotional response was one of profound loss and sadness. [Ms. A’s] death meant that there was a final end to her struggle and that there was no longer a possibility of a positive outcome. My sadness was especially intense as I was so aware of her strengths, which were unfortunately not enough in balance to deal with her despair and illness. The loss and sadness also involved the loss of [Ms. A], someone I knew and enjoyed. I did feel really sad that there was nothing that I or any of my supervisors could do to alter the final outcome.

Three years after the suicide, the therapist and a co-therapist who had a lengthy involvement in her treatment visited this patient’s parents in a distant city. Talking with them and visiting the patient’s grave helped both therapists achieve some degree of closure.

Guilt

On the open-ended question, 13 of the 26 therapists indicated that guilt was a major emotional response to their patient’s suicide. In response to a specific inquiry on the intensity scale, 16 therapists indicated moderate or severe guilt. Four of these saw their guilt reflected in their dreams or fantasies. One wrote that her office was flooded by melting snow leaking through the roof on the day after her patient’s funeral, forcing cancellation of her treatment sessions. She imagined the flood was punishment for her failure to prevent the suicide, and the water represented the tears of the grieving relatives she met at the funeral.

The therapists’ guilt often reflected their involvement with the patients, rather than their performance as therapists. On the intensity scale, all but one of the therapists experiencing guilt also experienced grief. This was clearly the response of the therapist just mentioned, whose guilty fantasy of being punished by the tears of the grieving relatives reflected her own intense grief and sadness over the loss of the patient.

Fear of Blame or Reprisal

Closely aligned with feelings of guilt were fears of being blamed for the patients’ suicides. Such fears were indicated by 11 therapists on the open-ended question and by 13 therapists on the scaled question. All 13 described guilt as part of their reaction to their patients’ deaths. Ten therapists, including seven of those who feared blame, were specifically afraid of being sued. These fears were most severe in two therapists who were threatened with the possibility of a lawsuit by their patient’s relatives. Another therapist recounted a nightmare in which he was being sued, although he was never actually threatened with a lawsuit.

Anger and Betrayal

Twelve of the therapists (14 in response to the scaled inquiry) indicated that anger had been one of their major emotional reactions to their patients’ suicides. Most saw their anger as stemming primarily from being rejected as a therapist by the patient; three of those who felt anger specifically noted a sense of betrayal. One wrote, “I felt angry at her rejection and destruction of the work we had done together. I felt betrayed that she had done something so lethal without giving me forewarning.”

Another described his feelings of anger, betrayal, fear, and embarrassment as follows:

I felt surprised and betrayed, for I believed that we had been able to establish something of a therapeutic relationship—perhaps the first such connection in this patient’s long experience with psychiatrists. Yet, at her most critical moment, she felt unable to contact me…. Other reactions included anger at having to find out about her death in the manner I did (from her parents a week after her death), embarrassment at having “lost” a patient for whom I felt responsible, fear that she died due to some gross oversight on my part which would eventually be discovered.

The sense of being wounded by what is perceived as a personal attack on the therapist’s competence was also described by a third therapist: “I was angry at being, I felt, tricked and betrayed by the patient, at her withdrawing from treatment, at her rejecting my efforts to help her…. I felt mistreated by the patient. She hadn’t cooperated with the treatment, hadn’t let me treat her, had made me look stupid.”

Self-Doubt or Inadequacy

Therapists described with some pain how their patients’ suicides shattered their confidence in their therapeutic abilities. Among their major reactions to the suicide, 11 therapists described self-doubt, seven described inadequacy, and four reported experiencing both.

Veteran therapists noted that they assumed their professional experience would protect them from fear and self-doubt, and they were shaken to find that it did not. Therapists in training questioned their ability to help anyone or even whether they were suited for their profession. As one put it, “It scared me, terrified me, left me doubting everything I did.”

Two therapists who felt both self-doubt and inadequacy in the aftermath of the suicide recalled vivid dreams of inadequacy. One wrote, “I had a series of ‘examination dreams.’ In these, I was striving to overcome obstacles to my arrival at, or competence in, college or internship duties. I was recurrently getting lost in a series of Kafkaesque corridors, stairways, or meandering trains, hopelessly late, woefully unprepared, or—in one dream—only partly clothed.”

Shame or Embarrassment

Six therapists felt shame or embarrassment provoked by their patients’ suicides. One therapist, whose patient was hospitalized shortly before her suicide, was ashamed of his response when his patient discontinued her therapy after discharge. He felt he had not made sufficient efforts to persuade her to continue therapy or to recontact him. After the patient’s death, shame and fear for his professional reputation led him to neglect reporting her suicide to the hospital psychiatrists.

Patterns of Emotion

Certain patterns appeared in collating these emotional responses. Grief and guilt seemed closely related; two of the four therapists who indicated feeling no guilt in response to a specific inquiry on the intensity scale were the only two therapists who did not feel even minimal grief at their patients’ deaths. One of them (case 4, see

Table 1) indicated no emotional response to his patient’s suicide; the other (case 5) indicated severe anger as his only emotional response. Guilt was also closely related to fear of blame; the 14 therapists who indicated moderate or severe fear of blame on the intensity scale were among the 16 who reported moderate or severe guilt. Included in this latter group were the 10 therapists who were specifically afraid of being sued. Three therapists reacted to their patients’ suicides with anger mixed with a sense of relief on the intensity scale. Their relief suggested, and their case presentations confirmed, that the anger toward the patients preceded the suicides and reflected the stress they felt in treating the patients.

Changes Therapists Would Make in Treatment

The therapist’s questionnaire included an open-ended item that asked, “In retrospect, were there any things you would have done differently that you think might have prevented the suicide?” Twenty-one of the 26 therapists identified at least one change they would have made in their patients’ treatment. The most commonly mentioned (by eight therapists) involved a change in medications. Seven therapists, of the 19 who were treating outpatients, indicated that they would have hospitalized the patient. Six responded that they would have consulted with previous therapists who had treated the patient.

Although no one can know whether such changes would have made a difference, given the outcome in these cases, it might be expected that the therapists would at least speculate about alternative treatment possibilities. Initially, however, five therapists responded that they would have done nothing differently. In one case, this attitude coexisted with an intense sense of having been responsible for the patient’s death, experiencing feelings of guilt, and having severe fears of being blamed. In another, the therapist also claimed to have had no emotional response to the patient’s death and seemed to have been minimally engaged with the patient. In the project workshops in which these five therapists participated, other participants were able to identify treatment changes that may have been helpful. During the course of the workshop, three of these five came to see that they were coping with their troubled feelings about their cases by denying the possibility that anything could have made a difference.

Support From Colleagues and Supervisors

Therapists were asked in the questionnaire about the reactions to their patients’ suicides from colleagues and, if applicable, from administrators, supervisors, and their own therapists. Overall, the therapists reported receiving adequate support from their colleagues. Therapists felt less isolated when colleagues and supervisors offered support, particularly when they shared their own experiences with the suicide of a patient. This sharing was more useful than peers’ or supervisors’ reassurances that the death was inevitable or even that the treatment had been a success. Nearly all therapists felt these assurances to be empty gestures. Some therapists returned to their own former therapists for help in dealing with their reactions and, in general, described these visits as useful in alleviating guilt over the patient’s suicide.

The situation was more complicated for therapists who were seeing patients as part of their training. Several among this group were troubled by what they felt were insensitive and unsupportive institutions that impeded their adjustment to the suicide. One of the more disturbing responses was described by a therapist who recounted his experience as a psychiatric resident at a military installation.

I found out [about the suicide] when I walked into our morning report to pick up the triage beeper and overheard them talking about suicide. I nonchalantly asked, “Who was it?” and found to my shock that it was [Mr. B]. I must have looked like I had been punched in the stomach, because the next question was, “Are you taking care of him now?” I walked to my office in a fog to find that the colonel in charge of our clinic had unlocked my office and was going through my desk to find the outpatient chart. I was too blown away to be angry at the colonel then, but now I’m angry again just writing it down. I remember sitting at my desk for what seemed like hours just staring into space—it was only minutes. All my colleagues looked at me differently and were either supportive to the point of irritation or on pins and needles. I was not even in the same world with my next few patients and began to question every decision I was making—in between fog coming in and out of my brain…. The M and M [mortality and morbidity] conference was not what I expected—I was angry at how it made a scapegoat of [Mr. B]: “We did a good job on this case, he didn’t let us help him,” for example. I was confused about my inability to be mad at him; however, I had no shortage of guilt. “What if I had done this?” “Was I clear enough?” played on my mind, ad infinitum.

Equally traumatizing was the treatment a psychology intern received from a major medical center teaching hospital.

In the days and weeks after [Ms. C’s] suicide my shame about my work as a therapist surfaced as I struggled with a burning sense of being inadequate, of not being good enough or good at all, of not being able to prevent her from dying…. My sense of living under a microscope was heightened several days after [Ms. C’s] suicide when I received a phone call from a mental health official who introduced himself and quickly proceeded to inform me our telephone conversation was being recorded, he was initiating an investigation into my patient’s death and I had the right to obtain legal counsel…. I was literally speechless for a few seconds and stammered that of course I would cooperate and, no, I didn’t think I would need an attorney. I realized the psychiatry department, the hospital, and the state mental health system would all be scrutinizing my work at a moment when I felt most vulnerable and beleaguered.…

To my surprise and dismay, many of the most difficult moments I experienced occurred during the psychiatry department’s meetings or “postmortems” held to review [Ms. C’s] treatment and suicide…. These meetings felt more like a tribunal or inquest. At the end of the first meeting, the clinical director, clearly displeased with the absence of several key people and my sketchy knowledge of [Ms. C’s] developmental and treatment history, abruptly ended the meeting and looked around the room and then fixed his gaze on me, proclaimed using words I will never forget: “It appears that [Ms. C] died the way she was treated, with a lot of people around her but no one effectively helping her.” I have to say this was one of the most helpless moments of my professional life. I remember feeling stunned and angry, that his comments were grossly unfair, inaccurate, and downright cruel. Yet I did not respond. I couldn’t, either out of anger, guilt, or shame or from sheer emotional exhaustion.

Interactions With Relatives

Therapists in 19 of the 26 cases saw their patients’ relatives after the suicides, either at their own or the relatives’ initiative. With discomfort, some attended the patients’ funerals. Most of these contacts with relatives were made with some trepidation and the expectation of anger and criticism. In almost all cases, however, the relatives were not critical of the therapist and often expressed gratitude for the help that had been provided. The therapists were most frequently relieved by the outcome of these interactions.

In two cases, the therapist and a surviving spouse entered into a therapeutic relationship in which each seemed to relieve the other’s guilt. In one such case, the therapist had been persuaded by the patient’s mother to encourage the patient’s discharge from a group home. Although the patient had responded by informing the therapist of his suicidal plans, the therapist had considered this reaction a problem to be worked through in therapy while planning for discharge continued. The patient then killed himself in exactly the manner he had described. Subsequently, the therapist and the patient’s mother spent some months informally discussing the patient’s death and suicide in general, almost as if they were two clinicians consulting on a case. The major purpose of the interaction appeared to be to reassure each other that they were not to blame for the patient’s death.

In the second case, the therapist appeared to have made little emotional contact with the patient, while empathizing with her husband. Although the husband initially felt that the therapist could have done more to prevent his wife’s suicide, he agreed to have the therapist treat him for depressive symptoms that he developed in the aftermath of her death.

Impact on Practice

Another questionnaire item asked the therapists to describe the influence of the suicide on their treatment of psychiatric patients in general and suicidal patients in particular. All indicated that they were now more alert and sensitive to the possibility of suicide. Most therapists also reported apprehension regarding the possible suicide of their other patients. Six described being anxious or reluctant to accept suicidal patients into their practices. Two of these countered an initial reluctance with a determination to treat such patients, rather than avoid them. Two others who felt no initial reluctance felt challenged by the experience and wanted to treat suicidal patients. One of them had made treatment and clinical research with suicidal patients a major part of his professional career.

Nine of the therapists had suicide contracts with their patients; the three therapists who indicated they felt betrayed were among this group. Although none of the nine renounced the use of suicide contracts, almost all felt less confidence in their usefulness.

Discussion

We cannot estimate how well our project participants represented all the therapists who experience the suicide of a patient. Although our clinical experience supervising and consulting in such cases suggests that these therapists are typical of therapists who had the same experience, the study’s requirements and procedures may have selected therapists who are more highly involved, more motivated, or more disturbed by a patient’s suicide.

Therapists who participated in this study had a need to explore and resolve long-lasting feelings connected with their patients’ suicides. We suspect that such a desire is widespread among therapists who lose a patient to suicide. Many therapists whose suicide cases did not meet the criteria for inclusion in the study nonetheless wished to share with us the experiences that still troubled them.

The intensity of the therapist’s emotional response to a patient’s suicide was independent of the therapist’s age, years of experience, or practice setting; even experienced therapists seeing patients in private practices experienced some strong and difficult reactions. Such therapists were among the most eager participants in this project and the quickest to acknowledge the value of their participation.

Therapists who were still in training at the time of their patients’ suicides generally experienced losses that were more public and generally more traumatic. The aggravated trauma inflicted by their institutions’ responses to the suicides made the project especially valuable to them. Even those who felt supported by their colleagues and their institutions reported that they did not learn much from the case reviews after the suicides. Therapeutic support groups provided them little relief; in the words of one therapist, “The group gave sympathetic support but did not add to my insight.”

Therapists were largely left to find their own relief. Many found talking to the patients’ relatives and attending the patients’ funerals helpful to them and to the decedents’ families. Treating a close relative after a suicide, as two therapists did, is problematic. Although such treatments might ease their immediate guilt, they are likely to impede and complicate both parties’ struggles to resolve their feelings. Little help was provided by the institutional reviews of the cases. One study

(8) has suggested that institutional psychological autopsies performed after a suicide increase most therapists’ self-doubts and distress. Institutional settings that alternate blame with empty reassurance hinder objective and thorough understanding of the suicide. But it is the process of learning all that one can from a situation that best relieves guilt and self-doubt and helps one go forward.

Our analyses revealed some consistent problems in the management of suicidal patients in the institutional setting. Medication problems were frequent in these cases; these will be addressed in a subsequent report. Many institutions lacked procedures for establishing communication between a patient’s current and previous therapists, or even between the institution’s own inpatient and outpatient staffs. Institutions should be able to identify and correct such gaps, but this can only occur when the postmortem review procedure both supports the therapist and fosters an honest examination of the treatment.

Therapists and institutions can more freely participate in reviews that do not threaten to levy judgments or sanctions. Independent institutions, like our foundation, are likely to be the most appropriate. Reviews conducted by disinterested outside groups that are knowledgeable about suicide can help therapists in private practices as well as those in institutional settings. Virtually all of the therapists who took part in our project felt that they learned from their participation and were helped to come to terms with the suicides. Our continuing efforts will extend this project to formally evaluate the effectiveness of these reviews in increasing therapists’ abilities to treat suicidal patients.