Despite the efforts of the National Institutes of Health to facilitate the systematic study of potential racial effects in patients with schizophrenia, there is still little we know about the relationship between race and biobehavioral measures

(1). Racial differences in neuropsychological functioning are expected to be found on the basis of results from nonclinical samples

(2–

5). As we indicated in an earlier article

(1), the majority of studies of schizophrenia fail to mention the racial composition of their study groups; some studies “control” for race, and a minority report racial effects that are inconsistent. The importance of reporting such differences inheres in possible racial differences in etiology and therapeutic strategies. The first step, however, is a rigorous assessment of whether such differences exist.

We took the opportunity to examine racial differences in a large (N=160) study of neuropsychological functioning in schizophrenia patients that was originally designed to assess sex differences

(6–

9). There are many complex conceptual and methodological issues regarding the relationships among race, ethnicity, social class, and culture that we will not address in this analysis, as it was not designed with those issues in mind. The study we conducted is, however, typical of neuropsychological studies of schizophrenia and provides a stepping stone for other, more comprehensive analyses. The first goal was to report simple racial differences in neuropsychological functioning. Neuropsychological functioning is known to correlate significantly with educational attainment

(10). It was important, therefore, to control for years of education

(11–

13). We did this statistically for both patients and the patients’ families of origin.

Method

Descriptions of patient recruitment and clinical assessment, neuropsychological testing, and methods of data reduction have been published elsewhere

(6,

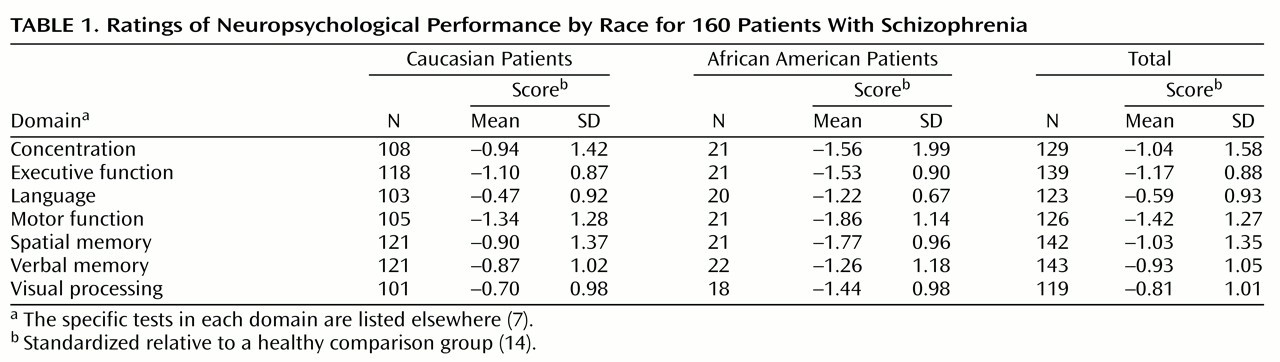

7). All procedures and materials were approved by our institution’s human investigations committee. Procedures were fully explained, and all patients provided written informed consent before participating in the study. We studied 160 (135 Caucasian and 25 African American) patients who met the DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and for whom we had neuropsychological test results and information about family education. Neuropsychological test scores were categorized into seven functional domains: concentration, executive function, language, motor function, spatial memory, verbal memory, and visual processing. Scores in these functional domains were standardized relative to a healthy comparison group.

We measured education in years completed for both patients and patients’ families. When this information was available for both of the patients’ parents, only the higher number of years of education was used in the analyses. We conducted two sets of analyses: a one-way (racial) analysis of variance on each of the neuropsychological domain scores and a one-way (racial) analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), using patient and family education as covariants.

Results

There were no significant differences in the percentage of men, mean age, or mean age at first hospital admission between the two racial groups. The Caucasian schizophrenia patients had a significantly higher mean number of years of education than did the African American patients (F=5.21, df=1, 155, p=0.02). This was also true for their parents (F=12.69, df=1, 158, p<0.0001).

Table 1 reveals that mean standardized neuropsychological domain scores were higher in the Caucasian group than in the African American group. Both groups had scores that fell significantly below those of the healthy comparison subjects, which was reflected in scores below 0, the mean score of the healthy comparison group. The racial effect was greatest on language (F=11.96, df=1, 121, p=0.001), followed by visual processing (F=8.64, df=1, 117, p=0.004), spatial memory (F=7.72, df=1, 140, p=0.006), and executive function (F=4.21, df=1, 137, p=0.04). Racial effects on concentration, motor function, and verbal memory were not statistically significant.

ANCOVAs controlling for patient and family education eliminated all statistically significant racial effects. Patient education effect sizes were larger than family education effect sizes for verbal memory (0.05 versus 0.01) and visual processing (0.06 versus 0.03). Family education yielded larger effect sizes than patient education on concentration (0.06 versus 0.05), executive function (0.02 versus 0.01), language (0.14 versus 0.11), motor function (0.07 versus 0.04), and spatial memory (0.11 versus 0.04). Pearson’s correlation coefficients between neuropsychological scores and patient and family education were all statistically significant at the 0.05 level. Coefficients ranged from 0.19 (executive function and patient education) to 0.48 (language and family education). Separate analysis by race yielded comparable results.

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is one of few to report the results of the analysis of racial effects in schizophrenia

(1). We believe this study is unique in the literature in that it examines the effects of the education of the family of origin on the neuropsychological functioning of patients with schizophrenia. It is of interest that family education had a larger effect than patient education on most domains of neuropsychological functioning.

In this study, all racial (African American and Caucasian) differences in neuropsychological functioning among schizophrenia patients were explained by education. Much of the covariance was carried by the educational level of the family of origin, suggesting that the results did not simply reflect an artifact of control for highly correlated patient characteristics.

Socioeconomic status, reflected in part by educational attainment, is a potentially powerful moderator of behavioral measures, particularly of neuropsychological function

(12,

13). It is reasonable to expect that the variability of social class of origin may contribute to the within-group performance variability that so frequently characterizes schizophrenia.