The massive changes in the health care system in the United States, especially in the last decade, are believed to have had important influences on the children’s mental health service system and its use, but few data are available to confirm these beliefs. Trends in psychiatric inpatient care for children and adolescents have been relatively neglected, in part because these patients represent only about 7% of the total mental health inpatient population

(1,

2). Inpatient services, however, are the most costly, estimated to account for almost half of the cost of annual mental health treatment for children and adolescents

(3). Moreover, despite considerable efforts to develop alternative types of care, there are children and adolescents for whom inpatient psychiatric care remains appropriate.

Results

Psychiatric discharges for children and adolescents constituted about one-tenth of the total population of psychiatric discharges from general hospitals from 1988 to 1995. Psychiatric discharges increased from about 7% of all discharges (psychiatric and general medical) for children and adolescents in 1988 to 10% in 1995.

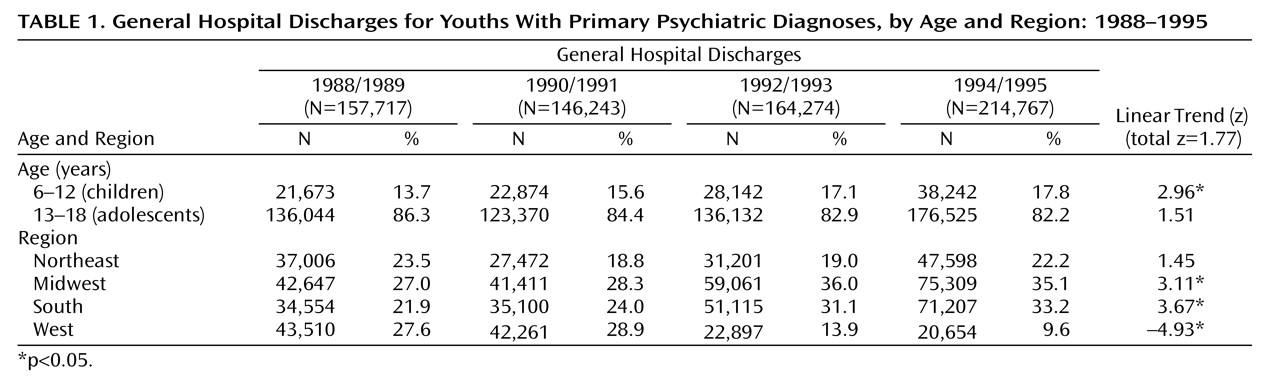

Table 1 shows that the number of discharges with a first-listed psychiatric diagnosis increased about 36% between 1988/1989 and 1994/1995, although the trend did not attain statistical significance. The rate of discharge (not shown in the table) also increased over that time period, from 373 to 418 discharges per 100,000 6–18-year-olds.

Table 1 also shows that adolescents consistently made up more than 80% of discharges. Over time, however, the number of discharges of children aged 6 to 12 increased significantly by about 76%.

Important regional differences emerged in the number of hospitalizations over time (

Table 1). Significant declines in the number of discharges were observed only in the West; the decrement was more than 50% in this region. By 1994/1995, discharges from the West constituted only 10% of all discharges. In contrast, there were significant increases in number of discharges in the Midwest (77%) and South (106%).

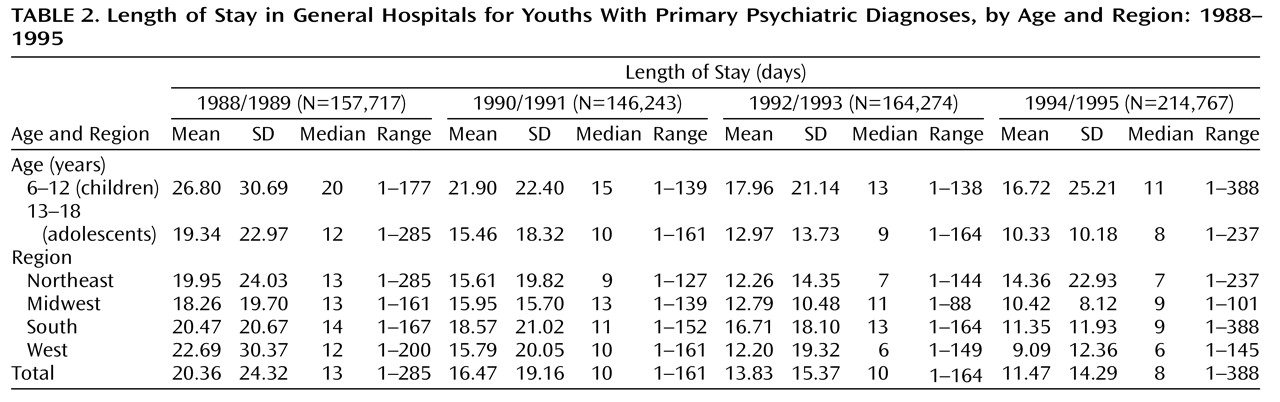

Table 2 documents changes in length of stay in days for these same variables. At the same time that discharges were increasing, mean length of stay was declining linearly—by approximately 9 days by 1994/1995. Taken together, there was a 23% decline in total number of days of care provided to children and adolescents with primary psychiatric diagnoses in general hospitals from about 3.2 million bed-days in 1988/1989 to about 2.5 million bed-days in 1994/1995.

Table 2 also shows that all children and adolescents experienced substantial declines in mean length of stay, but children invariably had longer lengths of stay than adolescents. Mean length of stay also declined most substantially in the West—from more than 3 weeks to just over a week. Over the study period, the median length of stay was declining similarly, from 13 to 8 days. Children had a longer median length of stay than adolescents did, and the median length of stay fell from 12 to 6 days in the West.

The most marked changes in diagnostic case mix were for nonpsychotic major depressive disorders, psychoses, and disruptive behavior disorders; there were significant increases in each case (not shown in the table). The number of discharges for nonpsychotic major depressive disorders increased 69%, from 50,428 in 1988/1989 to 85,266 in 1994/1995 (z=2.93, p<0.05). Discharges for psychotic disorders increased 63%, from 15,335 in 1988/1989 to 24,993 in 1994/1995 (z=2.20, p<0.05). Those for disruptive behavior disorders increased 55%, from 20,599 to 31,963 (z=2.15, p<0.05). There was a 34% decline in the residual (other) category of diagnoses, from 11,497 to 7,608 (z=–2.10, p<0.05). There were no significant changes in the numbers of youths with substance use disorders or adjustment disorders. No conclusions could be drawn regarding changes in number of discharges of youths with bipolar and anxiety disorders because of insufficient sample sizes.

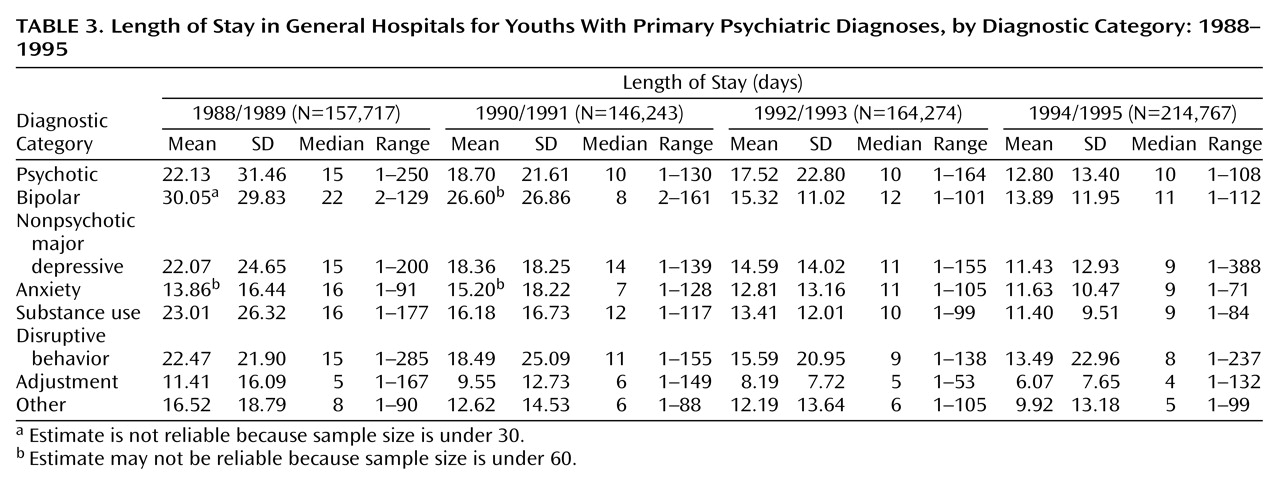

For each of the diagnoses that can be reliably estimated from the sample, there were reductions of at least 40% in mean length of stay (

Table 3). Over the study period, children and adolescents with adjustment disorders continued to have the shortest mean length of stay. In addition, the variability of length of stay declined. The range in mean length of stay fell from more than 1.5 weeks (11.41–23.01 days) to about 1 week (6.07–13.89 days). The standard deviation decreased for seven of the eight diagnostic categories over time (

Table 3).

The median length of stay for each diagnostic category also revealed declines in the number of days in care, as shown in

Table 3. The range in median length of stay declined from 17 days (5–22 days) to 6 days (5–11 days).

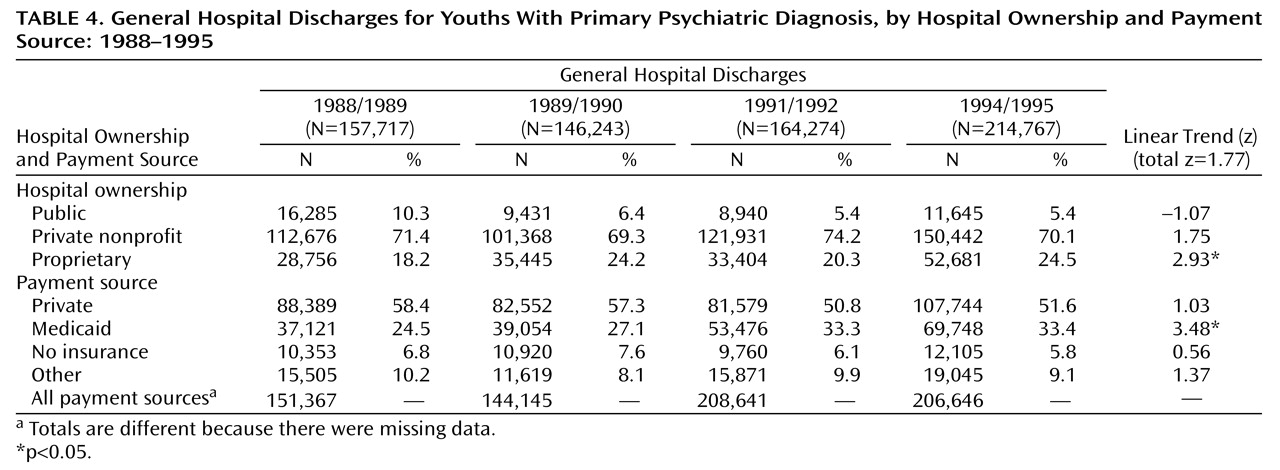

Table 4 shows that private nonprofit hospitals consistently provided most of the inpatient care for children and adolescents in general hospitals, about 70%. The number of discharges from private, profit-making (proprietary) hospitals increased significantly during the study period, by 83%. The number of discharges from public and private nonprofit hospitals did not change significantly, although the trends were in the expected directions: public hospital discharges declined about 29%, and private nonprofit hospital discharges increased about 34%.

Table 4 also reveals that Medicaid played an increasing role in financing psychiatric inpatient stays over the study period. Medicaid supported 88% more inpatient stays in 1994/1995 than in 1988/1989. This public insurance program financed about one-quarter of the hospitalized youths in 1988/1989, but it was supporting more than one-third of the youths by 1994/1995. The larger role of Medicaid accompanied the shift in the proportion of stays paid through private insurance: in 1988/1989, 58% of stays were privately financed; the comparable estimate for 1994/1995 is 52%. The number of discharges for the uninsured remained consistently low over the 8-year study period.

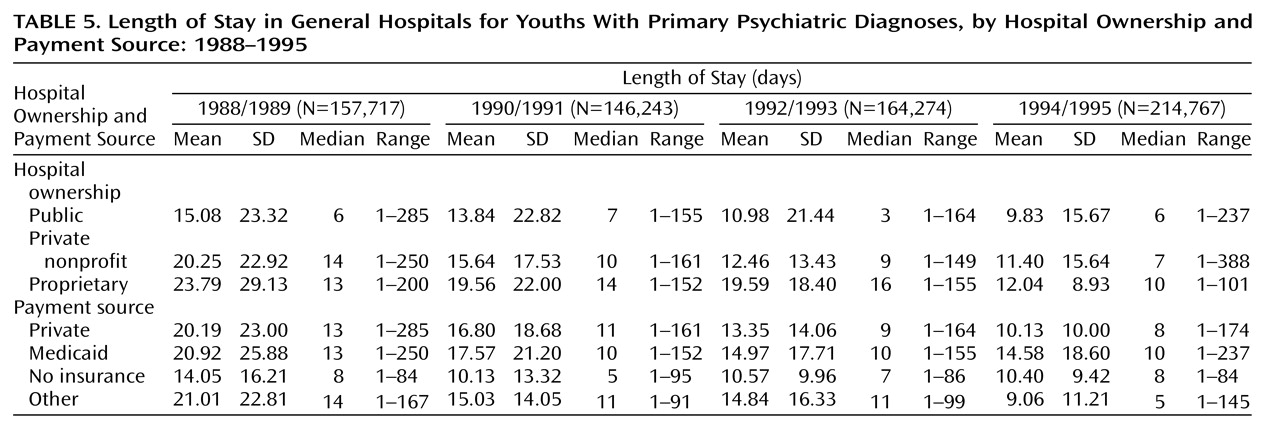

Over the study period, children and adolescents with psychiatric diagnoses in public hospitals had shorter lengths of stay than those in private hospitals. Mean length of stay was greatest in private, profit-making (proprietary) hospitals. However, differences in length of stay by hospital ownership diminished over time (

Table 5).

Table 5 also shows that mean and median length of stay declined more steeply for the privately insured (mean change=10 days; median change=5 days) than for Medicaid enrollees (mean change=6 days; median change=3 days). The net effect of the growth in the number of discharges financed through Medicaid, and the smaller decrement in length of stay for this group is that by 1994/1995 each financed about 40% of all psychiatric inpatient days. In contrast, private insurance paid for more than twice as many days of care than Medicaid in 1988/1989.

Discussion

In this nationwide analysis of psychiatric hospitalizations, we confirm the hypotheses that general hospital psychiatric discharge rates for children and adolescents increased while length of stay declined. These findings are consistent with trends found for psychiatric inpatient utilization by children and adolescents in the 1980s

(13,

14) and trends for adult psychiatric discharges between 1988 and 1993

(15). Although the dramatic decline in length of stay was partially offset by the increased number of discharges, the actual number of bed-days declined by 23%, leaving hospitals to contend with greater patient turnover and more unoccupied beds, a combination that could imperil the availability of psychiatric beds for children and adolescents in the future.

How to interpret the consequences of declines in length of stay for young people with psychiatric illnesses remains elusive. To our knowledge, there has been no outcome study with regard to psychiatric inpatient care for children and adolescents in this era of truncated length of stay. Shorter length of stay is associated with more residual symptoms and worse global functioning in depressed adults

(16). It is unclear whether children and adolescents are being discharged prematurely and may experience the same poor outcome or if alternative care has obviated lengthy hospitalization.

There were significant changes in the diagnostic case mix of the hospitalized children and adolescents over the study period, with striking increases in the proportion of those diagnosed with nonpsychotic major depressive disorders, psychoses, and disruptive behavior disorders. The substantial increase in the number of hospitalized children and adolescents with nonpsychotic major depressive disorders alone accounted for 61% of the increase in the total number of discharges between 1988/1989 and 1994/1995.

A number of factors might be driving this increase. First, nonpsychotic major depressive disorder, as experienced by young people, is a heterogeneous entity that can be inferred from an array of symptoms. In clinical practice, the severity and significance of symptoms are open to a certain degree of interpretation. Under the increased scrutiny of managed care, perhaps clinicians have increasingly adopted a depressive disorder as the primary diagnosis to justify a hospital admission, given the less obscure and less controversial standing of the depressive disorders. Second, research has shown that nonpsychotic major depressive disorders frequently are associated with suicidal and other dangerous behavior

(17). Managed care is likely to be responsive to dangerous correlates of depression.

The decrement in length of stay across all diagnostic categories is noteworthy because it may portend the erosion of clinical distinctions. Our finding is consistent with other research emphasizing that managed care strategies may not distinguish sufficiently among clinical or patient factors

(18). Children and adolescents most in need of inpatient care may suffer disproportionately under these developing pressures to expedite discharge indiscriminately.

Ultimately, changes in length of stay must be understood from a clinical perspective. Reductions are likely to lead to alterations in treatment. Shorter lengths of stay may bolster treatment modalities that focus on safety and crisis management and less on diagnostic clarification and treatment. The result may be counterproductive: Wickizer and colleagues

(19) have shown recently that reductions in length of stay lead to higher readmission rates among formerly hospitalized children and adolescents. Careful clinical outcome studies concerning the effectiveness and efficacy of treatment in the context of declining length of stay will be crucial additions to the literature.

Changes in discharges have occurred predominantly in the public and proprietary sectors of the market. Trends of declining discharges in the public sector that were visible between 1970 and 1980

(20) continue: from 1988/1989 to 1994/1995, the number and proportion of children and adolescents treated in public hospitals declined further, by about half. Historically, public hospitals played—and continue to play—a relatively small role in the inpatient care of psychiatrically troubled children and adolescents, in comparison to their significant role in the treatment of poor and severely ill adults. The private, profit-making hospitals, however, nearly doubled their admissions and increased their overall share in the child and adolescent psychiatric marketplace by six percentage points.

Hospital ownership appears to influence length of stay less over time, largely because of substantial declines in length of stay in the private sector. The convergence of hospital length of stay may represent further evidence of organizational homogenization of service standards, which appear to be driven by forces outside the organizations and relatively impervious to diagnostic considerations. Similar trends of a narrowing of length of stay variation have been observed among adults in the same National Hospital Discharge Survey data set, with the greatest erosion of length of stay from 1988 to 1994 occurring in private nonprofit hospitals

(15).

Public financing for inpatient psychiatric care for children and adolescents is increasingly important. By 1994/1995, Medicaid financed a similar proportion of psychiatric days of care (40%) as private insurance, representing another significant shift in the distribution of the psychiatric inpatient population of children and adolescents. Over this same time period, length of stay dropped more dramatically for the privately insured to the point that in 1994/1995 they had shorter lengths of stay than publicly insured youth. This may reflect differences in penetration by managed care for each of these markets. By 1994/1995, some degree of managed care was virtually ubiquitous in the private insurance industry, but less than 30% of the Medicaid population was enrolled in managed care programs

(21). As managed care in public programs continues to expand, we might expect further reductions in length of stay among this population.

There are other factors that might account for longer length of stay for the Medicaid population relative to the privately insured population. Publicly insured children and adolescents tend to have more psychiatric problems and risk factors, such as history of foster placement, single-parent family status, and low family income

(5). A potentially important contributor to longer length of stay for children and adolescents covered by Medicaid is also placement difficulty, a problem almost negligible for privately insured youths but common for poor youths with psychiatric problems

(5).

These data also capture important regional differences in inpatient psychiatric care for children and adolescents in general hospitals, differences that became more pronounced over the period studied. The combination of reduced discharge rates and length of stay in the West could reflect the greater encroachment by managed care in this region and foreshadow trends for the rest of the nation.

These data help to build a profile of recent changes in inpatient care for children and adolescents, but they have a number of important limitations. First, the study focuses exclusively on general hospitals and, therefore, does not inform us about changes in care in psychiatric hospitals or residential facilities. Second, the small sample sizes limit our ability to study subgroups in more depth. The data also do not include standard indexes of severity, family characteristics, and treatment utilization, limiting the kinds of analyses that could be pursued. There is consistency in the diagnoses reported, but reliability in reporting does not guarantee accuracy, so this, too, should be viewed with some caution. Finally, these data are based on discharges, not on individuals; therefore, we can only speculate as to whether increases in discharges reflect increased access or whether they signal greater readmission rates due to substantial declines in length of stay.

Despite the limitations, there is sufficient strength in the data to suggest that the landscape of inpatient services for young people with psychiatric illnesses has changed substantially. It is reasonable to expect that these changes will likely continue. Moreover, these trends can be attributed more to evolving market forces and characteristics of the hospitals than to transformations in the populations served. Further penetration by managed care, especially into the public insurance system, as well as changes in Medicaid policy, could undermine inpatient resources.