Major depression is frequently characterized by hypercortisolemia

(1–

5). Open trials suggest that cortisol synthesis blockers or cortisol receptor antagonists, including ketoconazole

(6,

7), RU-486

(8), and metyrapone

(9), may exert antidepressant effects. Conversely, increasing cortisol levels, through the administration of glucocorticoids, may also have antidepressant effects

(10).

There are only limited controlled data on either type of strategy in major depression, however. In a positive, controlled trial by Arana et al.

(11), depressed patients were evaluated at baseline and then randomly assigned to receive 4 days of treatment with oral dexamethasone (4 mg/day) or placebo. Thirty-seven percent of patients treated with dexamethasone demonstrated a greater-than-50% reduction in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores, in contrast to 6% of placebo-treated patients. Since this was an outpatient study, compliance with the oral study medications could not be assured.

Dexamethasone may not be an ideal antidepressant because it can produce more dysphoria than does hydrocortisone

(12) and may not cross the blood-brain barrier as efficiently

(13). Indeed, in a small pilot study of depression, Wolkowitz et al.

(14) found little benefit in intravenously administered dexamethasone. On the other hand, hydrocortisone was found to effectively improve mood in a small controlled study of patients with major depression, dysthymia, and adjustment disorder

(15).

We now report on a prospective study of the antidepressant effects of intravenous hydrocortisone and ovine corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) under rigorous double-blind conditions in a group of well-characterized patients with major depression.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were recruited by advertisement and from the outpatient and inpatient services of the departments of psychiatry at Stanford University Medical Center, McLean Hospital (Belmont, Mass.), and Washington University School of Medicine (St. Louis). At screening, subjects had a clinical interview including a psychiatric history and were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID)

(16) and the 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(17). All raters had undergone training and were certified for interrater reliability on the SCID and Hamilton depression scale.

Patients were required to have a diagnosis of unipolar major depression, with an episode of at least moderate severity without psychotic features. They were also required to have a Hamilton depression scale score of at least 21; a score of at least 7 on the eight items of the Thase Core Endogenomorphic Scale

(18), which are included in the 21-item Hamilton depression scale; and no alcohol or substance abuse in the past 6 months. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient after the procedures had been fully explained.

Patients had been free of psychiatric and nonpsychiatric medications for at least 2 weeks, with no fluoxetine for 6 weeks, no depot neuroleptics for 3 months, and no ECT for 6 months. Additionally, patients were required to have no active medical problems and to have normal physical and laboratory examinations.

Procedure

The study reported here was part of a larger protocol on the biology of psychotic and nonpsychotic major depression conducted in the general clinical research centers at Stanford University Medical Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston), and Washington University School of Medicine. The larger study was approved by the institutional review boards of all facilities, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Subjects were admitted to the general clinical research center at 4:00 p.m. on day 0 and had intravenous lines inserted at that time. From 6:00 p.m. on day 0 to 6:00 p.m. on day 1, blood samples were collected hourly for cortisol and ACTH. At 7:00 p.m. on day 1, each subject was given an intravenous push containing either ovine CRH 1 μg/kg or placebo and an infusion over 2 hours containing hydrocortisone 15 mg or placebo. Each subject received one or no active substance. Subjects were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions. The choice of doses of ovine CRH and hydrocortisone was based on previous studies finding that these doses resulted in cortisol increases in the physiological range

(19,

20).

The infusions and ratings were conducted under double-blind conditions. The Hamilton depression scale was administered at 4:00 p.m. on days 0, 1, and 2. We excluded from the results subjects who had Hamilton depression scale scores of less than 18 on day 1 prior to the infusion or who had shown a 25% decrease in the Hamilton depression scale from day 0 to day 1. The full neuroendocrine data from this study will be presented elsewhere.

Treatment effects were tested with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in which treatment (hydrocortisone, ovine CRH, or placebo) was the single factor tested and the dependent variable was change in Hamilton depression scale from day 1 to day 2. If the omnibus test of group differences was statistically significant, pair-wise comparisons between treatments were made with the Bonferroni procedure. Group differences in baseline demographic and clinical variables were tested with one-way ANOVA for continuous variables and the chi-square statistic for categorical analysis. All analyses were performed with SPSS Version 7.5.2 software (SPSS, Inc., Cary, N.C.).

Results

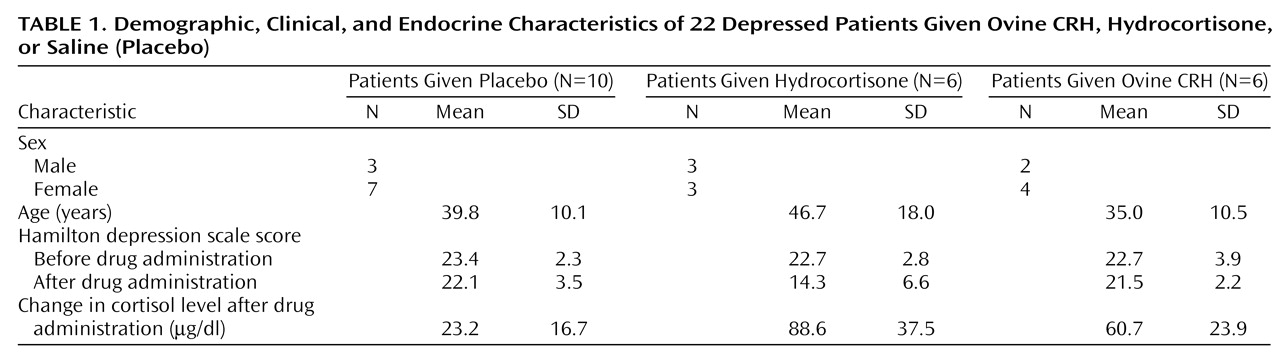

Twenty-two patients were available for analysis: 10 received saline, six received hydrocortisone, and six received ovine CRH (

Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences among the three groups in sex distribution, age, or baseline Hamilton depression scale scores. The mean length of the current depressive episode was 80.3 months (SD=125.9), and the mean number of previous major depressive episodes was 5.1 (SD=5.6). Thirteen of the 22 patients had a current depressive episode of less that 2 years. Thus, the study group included patients with acute depression and those with chronic depression.

Patients who received hydrocortisone showed a mean decrease in Hamilton depression scale score of 8.4 (representing a 37% reduction) from day 1 to day 2, compared with a mean decrease of 1.2 points in the ovine CRH group and 1.3 points in the placebo group. Data analysis revealed that these group differences were statistically significant (F=8.0, df=2, 19, p<0.01). Post hoc tests indicated that the hydrocortisone group improved significantly more than both the ovine CRH (p<0.05) and placebo (p<0.01) groups.

Discussion

Intravenous administration of a moderate dose of hydrocortisone appears to produce robust and rapid improvement in Hamilton depression scale scores. There are several possible explanations for this effect. One hypothesis is that the acute administration of a glucocorticoid reduces hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal hyperactivity overall through a negative feedback on the hypothalamus

(11). Another possibility is that rapid elevation in mood is an indirect effect of hydrocortisone in enhancing another neurotransmitter system, such as dopamine

(21). A third possibility is that some depressed patients may have mildly low cortisol activity

(22); administering hydrocortisone to such depressed patients would correct this deficiency. Finally, it has been proposed that hydrocortisone might improve mood by increasing β-endorphin levels

(15).

Ovine CRH did not appear to produce the same improvement in the total Hamilton depression scale score as did hydrocortisone. A review of symptom change scores revealed that ovine CRH and cortisol both improve core endogenous depressive symptoms (Core Endogenomorphic Scale) but that ovine CRH was associated with an increase in anxiety. Thus, the improvement in Core Endogenomorphic Scale items was offset by worsening of anxiety items, so that ovine CRH did not improve total Hamilton depression scale scores. Another possible explanation for the lack of Hamilton depression scale improvement with ovine CRH is that the dose of ovine CRH used did not produce as great a rise in serum cortisol as did the hydrocortisone infusion (

Table 1). Alternatively, the effects of hydrocortisone on mood may be more specific than those of ovine CRH. Although ovine CRH does not cross the blood-brain barrier

(23), intravenous ovine CRH stimulates a variety of other hormones and peptides (e.g., β-endorphin and catecholamines in addition to ACTH and cortisol) that may not have salutary effects on mood.

There are several limitations in this study, including the small size of the study group and the brief treatment and follow-up. It would be useful to establish how enduring the antidepressant effects of hydrocortisone are as well as how effective multiple-day administration may be.

Clinical experience indicates that long-term administration of high doses of glucocorticoids can have deleterious mood and physical effects; however, glucocorticoids may have therapeutic effects on depression and have also shown potential in treating other conditions, including alcohol withdrawal

(24). This study suggests that some depressed patients may benefit, at least temporarily, from acute administration of intravenously administered glucocorticoids. A potential application, for example, might be to apply acute intravenous administration of glucocorticoids for brief periods to speed antidepressant response. Further study is needed to define the mood effects of specific steroids on subtypes of depression and, if useful, the optimal dose and length of administration. Last, specific glucocorticoid or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists can be employed with cortisol administration to test the hypothesis that the antidepressant effects of hydrocortisone are mediated by steroid receptors.