Prediction of Alzheimer’s Disease at Follow-Up

Women were more likely than men to receive a final diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (χ2=4.8, df=1, p<0.05). Age (t=3.2, df=75, p<0.01), fewer years of education (t=2.4, df=75, p<0.05), low baseline modified Mini-Mental State scores (t=3.1, df=75, p<0.01), and low baseline olfaction scores (t=3.4, df=75, p<0.001) were each associated with the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease at follow-up. Family history of dementia and baseline scores on the Blessed Functional Activity Scale and the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale were not associated with a final diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Sixteen of 64 patients who reported no problems smelling, compared to three of 13 patients who reported problems smelling, had developed Alzheimer’s disease by follow-up (n.s.).

Low olfaction scores (≤34) predicted the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease at follow-up (19 of 47 with low olfaction scores developed Alzheimer’s disease compared to zero of 30 with high olfaction scores) (χ2=16.1, df=1, p<0.001); all 19 patients with mild cognitive impairment who developed Alzheimer’s disease had low olfaction scores. Low olfaction scores accompanied by subjective report of no problems smelling were present in 16 of 19 patients who met the criteria for Alzheimer’s disease at follow-up compared to 21 of 58 who did not meet (or had not yet met) the criteria for Alzheimer’s disease at follow-up (χ2=13.2, df=1, p<0.001). When we examined cutoff points for “low olfaction score” across the 30–36 (≤30 to ≤36) scoring range, low olfaction plus lack of awareness remained a significant predictor of Alzheimer’s disease (χ2=8.9–13.2, df=1, p<0.01–0.001). Fourteen of 19 who developed Alzheimer’s disease had low olfaction plus lack of awareness at a cutoff point of ≤33, 16 of 19 who developed Alzheimer’s disease had low olfaction plus lack of awareness at a cutoff point of ≤35 (or ≤34; cutoff used in the analyses), and 16 of 19 who developed Alzheimer’s disease had low olfaction plus lack of awareness at a cutoff point of ≤36. Among patients with mild cognitive impairment, only three (3.9%) of 77 reported problems smelling but scored ≥35 on the olfaction test.

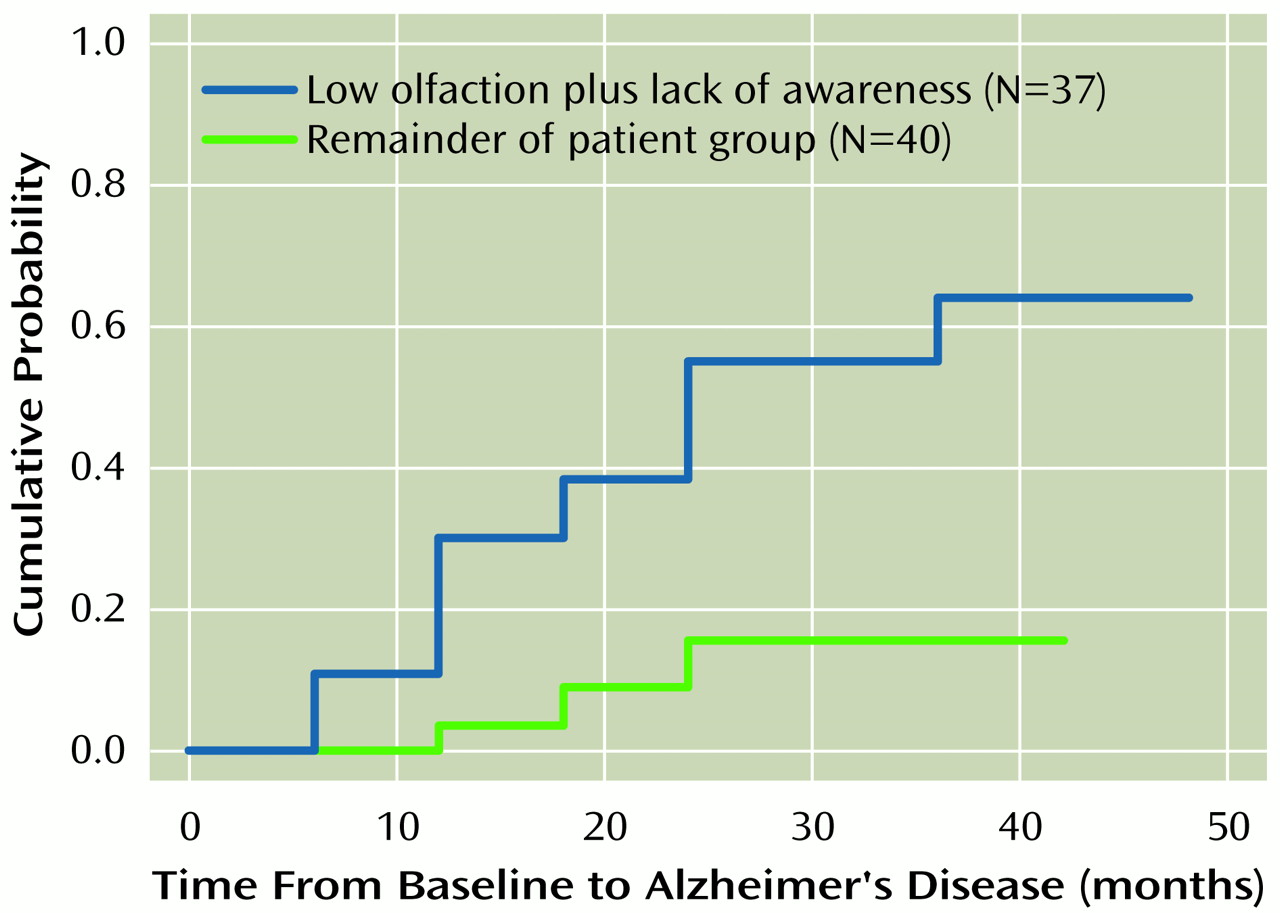

The Kaplan-Meier survival curve for patients with low olfaction plus lack of awareness, compared to that for the remainder of the patient group, is presented in

Figure 1. In a Cox proportional hazards model, olfaction scores alone predicted time to develop Alzheimer’s disease (χ

2=8.8, df=1, p<0.005), but subjective reports of problems smelling analyzed alone were not predictive of Alzheimer’s disease. In Cox analyses, low olfaction scores (or olfaction scores dichotomized as ≤34 versus >34) were not significantly predictive when age (n.s.), sex (n.s.), modified Mini-Mental State score (n.s.), and years of education (n.s.) were entered into the same model. Low olfaction plus lack of awareness was a significant predictor (relative risk=7.3, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.7–23.1, p<0.01) of time to develop Alzheimer’s disease when age (n.s.), sex (n.s.), modified Mini-Mental State score (n.s.), and years of education (n.s.) were also included in the Cox model. This effect remained when, instead of modified Mini-Mental State score, the attention (Target Finding Test letter cancellation task) or memory (Selective Reminding Test total recall task) measures were included in this model with low olfaction plus lack of awareness (attention: relative risk=10.7, 95% CI=2.5–41.0, p<0.005; and memory: relative risk=4.7, 95% CI=1.2–18.2, p<0.05). Low olfaction plus lack of awareness remained a significant predictor of time until the development of Alzheimer’s disease (relative risk=7.3, 95% CI=1.8–42.7, p<0.01), even after entering age (n.s.), sex (n.s.), and all three neuropsychological measures (modified Mini-Mental State score [n.s.], attention measure [p<0.02], and memory measure [n.s.]) into the same Cox model.

For each olfaction score in the 31–36 range, the low olfaction plus lack of awareness variable remained a significant predictor of time to develop Alzheimer’s disease in Cox analyses that included age, sex, years of education, and modified Mini-Mental State score as covariates. For an olfaction score of ≤30, the values for low olfaction plus lack of awareness were not significant.

Additional Cox analyses were conducted separately in the subgroup with high baseline Mini-Mental State scores (≥27 of 30, N=52); low olfaction plus lack of awareness remained a significant predictor of time until the development of Alzheimer’s disease (relative risk=10.8, 95% CI=1.1–105.0, p<0.05) when age, sex, years of education, and baseline Mini-Mental State score were included in the model. In this subgroup with high scores on the Mini-Mental State, eight of nine patients who met the criteria for Alzheimer’s disease had baseline low olfaction plus lack of awareness ratings compared to 15 of 43 who did not meet (or had not yet met) the criteria for Alzheimer’s disease (χ2=8.8, df=1, p<0.01). The nine patients with high Mini-Mental State scores who were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease at the 2-year follow-up had significantly lower baseline olfaction scores (mean=27.1, SD=5.9) than the 43 patients who were not diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease at the 2-year follow-up (mean=34.1, SD=4.6) (t=3.8, df=51, p<0.001).

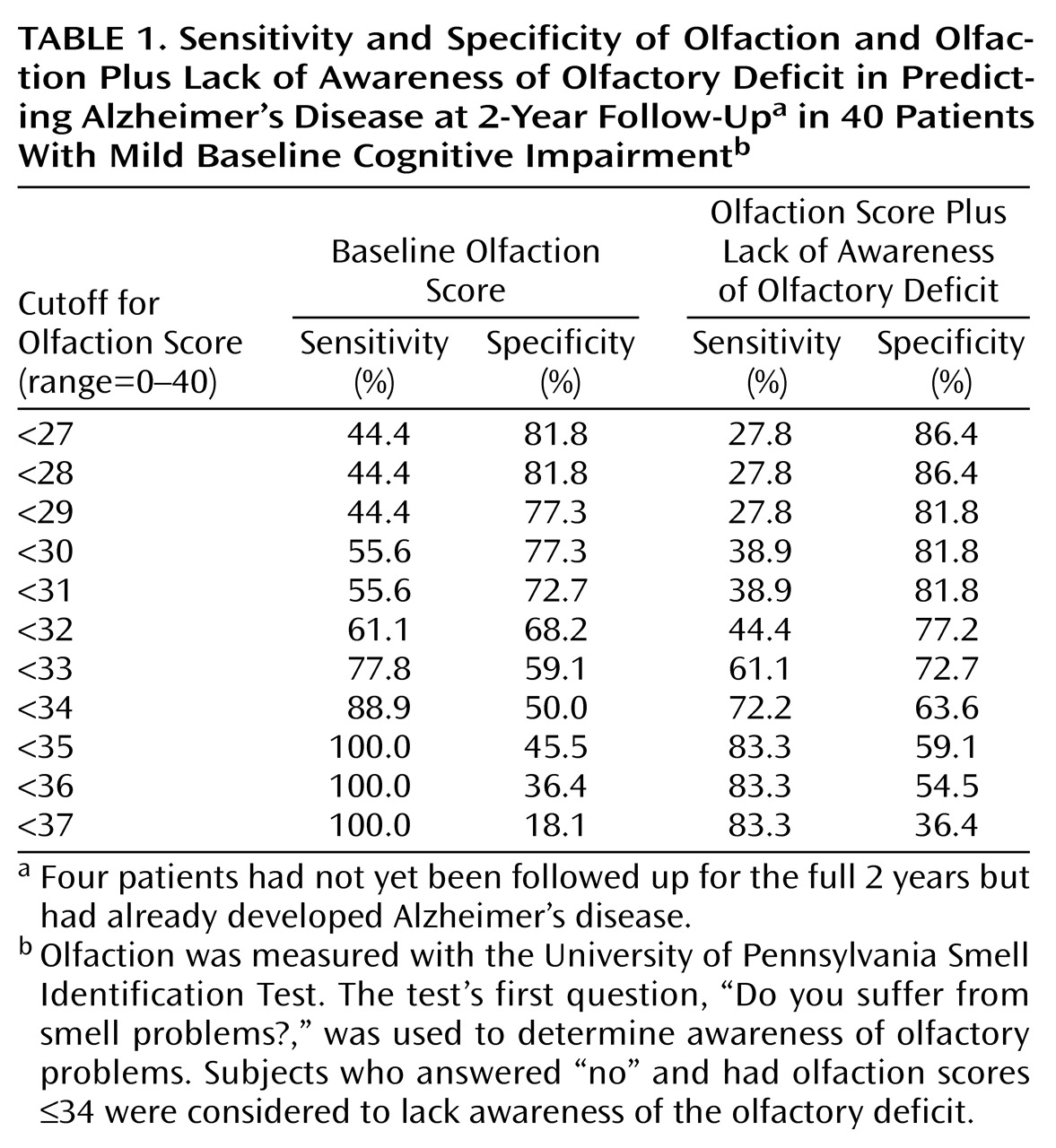

To evaluate clinically relevant prediction in the intermediate term, further analyses were conducted by restricting the clinical group with mild cognitive impairment to the patients who had completed 2 years of follow-up (N=36) or had already developed Alzheimer’s disease by 2 years (N=4). In this subsample of 40 patients with mild cognitive impairment (18 who had and 22 who had not developed Alzheimer’s disease), baseline olfaction scores were lower in those who had developed Alzheimer’s disease (mean=26.3, SD=7.7) than in those who had not (mean=31.5, SD=7.4) (t=2.1, df=38, p<0.05). Fifteen of 18 patients who met the criteria for Alzheimer’s disease at the 2-year follow-up had low olfaction plus lack of awareness at baseline compared to nine of 22 who had not met (or have not yet met) the criteria for Alzheimer’s disease (χ2=7.4, df=1, p<0.01). In survival analyses that evaluated the outcome of Alzheimer’s disease at the 2-year follow-up, low baseline olfaction scores (or olfaction scores dichotomized as ≤34 versus >34) did not predict Alzheimer’s disease when age, sex, modified Mini-Mental State score, and years of education were also included in the model. However, low olfaction plus lack of awareness at baseline was a significant predictor of Alzheimer’s disease (relative risk=6.4, 95% CI=1.5–26.8, p<0.01) when age, sex, modified Mini-Mental State score, and years of education were also included in the model. Similarly, for patients who had completed the 2-year follow-up, logistic regression analyses revealed that low olfaction plus lack of awareness at baseline was a significant predictor of Alzheimer’s disease (odds ratio=13.1, 95% CI=1.6–116.0, p<0.05) when age, sex, modified Mini-Mental State score, and years of education were also included in the model.

For this subgroup followed up at 2 years, baseline olfaction total scores of ≤34 led to 100% sensitivity and 45.5% specificity for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, including a progressive decrease in sensitivity and an increase in specificity with lower olfaction scores (

Table 1). Comparable figures were obtained for the low olfaction plus lack of awareness variable by using a wide range of cutoff points for “low olfaction score” (

Table 1). For both olfaction variables, the optimal tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity appeared to be in the 30–35 scoring range.

The apolipoprotein E genotype was evaluated in 77 patients with mild cognitive impairment. Only 11 (14.3%) of the 77 patients with mild cognitive impairment had the apolipoprotein E ε4 allele (hetero- or homozygous), and four of these 11 patients had developed Alzheimer’s disease. There was no association between the presence of the ε4 allele and either of the olfaction measures or the outcome of Alzheimer’s disease, but the small number of patients with the ε4 allele precluded meaningful statistical analyses.