The problem of differentiating primary from secondary negative symptoms in schizophrenia has been a focus of considerable attention over the last few years. Well-known sources of secondary negative symptoms are drug-induced akinesia, depression, psychotic symptoms, social deprivation, and chronicity

(1). However, the problem of how to disentangle the relationships between primary (i.e., illness-related) and secondary sources of negative symptoms remains unresolved. According to Miller et al.

(2), two main strategies have been used to distinguish between primary and secondary negative symptoms. In one strategy, a rater makes a subjective judgment of whether negative symptoms are primary or secondary. The other strategy involves a statistical adjustment for putative secondary sources. Although the latter approach is very complex and hardly applicable to a clinical setting, it remains the best method for differentiating primary from secondary negative symptoms under research conditions

(3).

Disentangling the primary from the secondary sources of negative symptoms is important for a number of reasons, including implementing appropriate treatment strategies. Numerous studies have analyzed the covariation between negative symptoms and their putative secondary sources (i.e., psychoticism, neuroleptic side effects, or depression), but most of them have been conducted with neuroleptic-treated patients. The predominance of treated patients in these studies represents an important problem, because neuroleptics may produce akinesia that mimics negative symptoms and may also cause depression, which may mimic negative symptoms. The question is even more complex if one considers that neuroleptics may have different therapeutic effects on primary and secondary negative symptoms, thus rendering the differentiation process very difficult

(4).

In an attempt to overcome this problem, the neuroleptic withdrawal paradigm has been used to examine the extent to which negative symptoms change or covary over time with their potential secondary sources

(2,

5,

6). However, this paradigm is subject to numerous limitations, the main one being that the neuroleptic-free period is too short (typically 1 month or less) to rule out the long-lasting therapeutic effects and side effects of neuroleptics. Other limitations include the use of study groups of patients with high levels of chronicity or the use of depression rating scales that blur the distinction between the symptoms of depression and the negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

Perhaps the two most important questions in studying the relationship between drug-induced and primary negative symptoms are 1) how drug-induced parkinsonism is ascertained and 2) how it is related to negative symptoms. Regarding the first question, it is generally assumed that the presence of parkinsonism in treated patients is a direct effect of neuroleptics. This assumption overlooks the possibilities that parkinsonism may be an indigenous feature of schizophrenia

(7,

8) and that primary parkinsonism may improve under neuroleptic treatment

(9). If both suggestions are true, then parkinsonism in patients who are taking neuroleptics may not necessarily be drug-induced and the attribution of parkinsonism to a direct side effect of treatment may be misleading. The second question, a theoretical one, deals with phenomenological similarities between certain negative symptoms (particularly affective flattening and alogia) and certain parkinsonian symptoms (i.e., akinesia). Because of these similarities, a finding of an association between the ratings of negative symptoms and of parkinsonism does not necessarily mean that the former are a consequence of the latter. The same question applies to the differentiation of drug-induced akinesia from depression, thus complicating the distinction between primary and secondary negative symptoms even further.

To avoid these shortcomings, we undertook the study reported here using a paradigm in which possible sources of negative symptoms (psychosis, parkinsonism, and depression) were examined in neuroleptic-naive patients before and after they started neuroleptic treatment. The purpose of using this paradigm was to avoid the higher levels of chronicity in patients who had been previously treated with neuroleptics and to control for the effect of treatment on negative and parkinsonian symptoms. In addition, we used a measure of depressive symptoms specifically developed for patients with schizophrenia to avoid contamination of the measure with items that might reflect negative symptoms. The specific objectives that we pursued were 1) to identify the determinants of negative symptoms in neuroleptic-naive patients, 2) to identify the determinants of negative symptoms in these patients at discharge, when their psychopathology was in remission and the patients were taking neuroleptics, and 3) to determine whether change in negative symptoms over the treatment period covaried with change in secondary sources of negative symptoms.

Method

Subjects

The study subjects consisted of 47 psychotic patients consecutively admitted to the Psychiatric Unit of the Virgen del Camino Hospital in Pamplona, Spain, who had never been treated with neuroleptics. The history of previous psychopharmacological treatment was carefully assessed by means of interviews with each patient, the patient’s relatives, and, if appropriate, the patient’s primary physician. Clinical symptoms and diagnosis were assessed by the first author by using the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History

(10). To be included in the study, patients had to meet DSM-IV criteria for a functional psychotic disorder that was not primarily affective. Final DSM-IV diagnoses were assigned by consensus between the first author and the patient’s attending clinician on the basis of the results of the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History and all other available information about the patient. The exclusion criteria were a history of drug abuse, evidence of organic brain disorder including mental retardation, somatic disease, or premature discharge before inpatient treatment was complete. The diagnoses of the study subjects were schizophrenia (N=25), schizophreniform disorder (N=15), schizoaffective disorder (N=2), and brief psychotic disorder (N=5). All subjects were experiencing their first admission. Written informed consent was obtained after the study procedure had been explained.

The mean age of the subjects was 26.9 years (SD=9.1), and they had a mean educational level of 10.3 years (SD=3.1). Thirty-three patients were male, and 39 were single. The mean length of illness, determined from the time the patients first exhibited illness-related behavioral symptoms, was 24.2 months (SD=46.1), and the mean time since the patients first exhibited formal psychotic symptoms was 12.8 months (SD=20.7).

Treatment Variables

At admission none of the patients was taking psychotropic drugs, but over the illness course four patients had been exposed to benzodiazepines and two patients to antidepressants.

After baseline assessment at admission, all patients were treated under open conditions by using monotherapy with an antipsychotic chosen by the patient’s treating clinician and administered on an individual dose regimen. Eight patients were treated with haloperidol, 28 with risperidone, and 11 with olanzapine. At discharge, 14 patients were taking biperiden because they had developed clinically meaningful parkinsonism over the treatment period. Other psychotropic drugs administered to the patients during the treatment period included hypnotics (N=12), anxiolytics (N=9), antidepressants (N=3), and mood stabilizers (N=1).

Given that the traditional chlorpromazine-equivalents approach for determining comparable doses of different medications does not entirely apply to atypical neuroleptics, we used the daily raw dose in milligrams and a 5-point scale for clinical dose levels to compare the doses of neuroleptics administered during treatment

(11). We calculated the average daily dose levels over the treatment episode and the dose levels at the day of discharge by using both measures. Because there was a high correlation between both determination methods (r>0.90), for the remainder of the article we will refer to the dose level in milligrams per day. The average dose of neuroleptics administered to patients over the hospitalization period was 9.66 mg/day (SD=5.4), and at discharge the average dose was 7.63 mg/day (SD=5.9).

Assessment

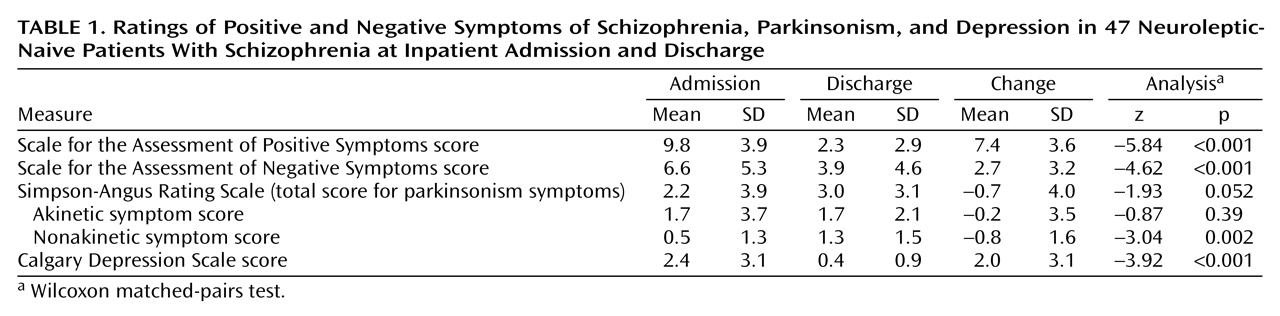

The patients’ psychopathology was evaluated by the first author within a few hours after admission, before the patient started neuroleptic treatment, and on the day of discharge an average 3.3 weeks (SD=1.6) after admission. Positive and negative symptoms were assessed by using the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS)

(12) and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)

(13), respectively; both scales are included in the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History. Given that inattentiveness is not a negative symptom, the SANS total score was determined by summing the global ratings for affective flattening, alogia, avolition/apathy, and anhedonia/asociality. Depression was assessed by using the Calgary Depression Scale

(14) and parkinsonism by using the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale

(15).

The total score on the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale was divided into a score for akinesia (items reflecting akinesia and rigidity) and a score for nonakinetic parkinsonism (glabella tap, salivation, and tremor), because akinesia phenomena represent the aspect of drug-induced parkinsonism most likely to be confused with negative symptoms

(16). In a previous study, we have shown the usefulness of separating the two kinds of ratings for assessing drug-induced parkinsonism that mimics negative symptoms and for examining the differential effects of neuroleptics on the two kinds of symptoms

(4). In the study group, a factor analysis of the mean change in the 10 parkinsonian items over the treatment period (data not shown) revealed a clear-cut two-factor solution, with akinetic and nonakinetic items loading on separate factors, thus suggesting that both ratings evolved independently during treatment.

Statistical Procedures

Scores for the SAPS, SANS, Calgary Depression Scale, and the two parkinsonian ratings were examined by using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to determine whether they were normally distributed. The scores for parkinsonism and depression at admission and discharge and the scores for positive symptoms at discharge were not normally distributed. After rescaling the raw scores to avoid null values, these variables were log transformed and tested for normality. Again, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests showed that the log-transformed variables were not normally distributed. Given that it was not possible to normalize these scores, the raw scores were used in the multivariate analysis.

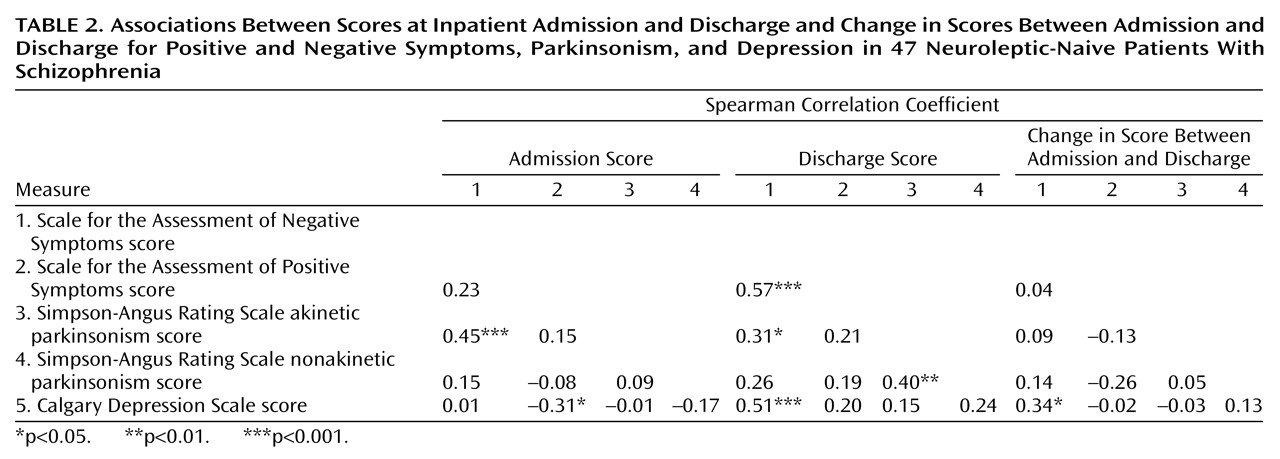

Within-group differences in symptom scores at admission and discharge were examined by using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs test. Spearman rank correlation coefficients were used to examine the association among variables at admission and at discharge and the mean change in their scores between the two assessment points. Finally, stepwise linear regression analysis was used to determine the relative contribution of each putative secondary source of negative symptoms in explaining the SANS total score. The coefficient of determination (R2) added at each step, multiplied by 100, was used to designate the proportion of variance in negative symptoms accounted for by the secondary sources. We acknowledge that measurement error could contribute to variability in the negative symptoms that was not accounted for by the secondary sources we examined. Despite this possibility, that variance was considered to represent “primary” or illness-related negative symptoms.

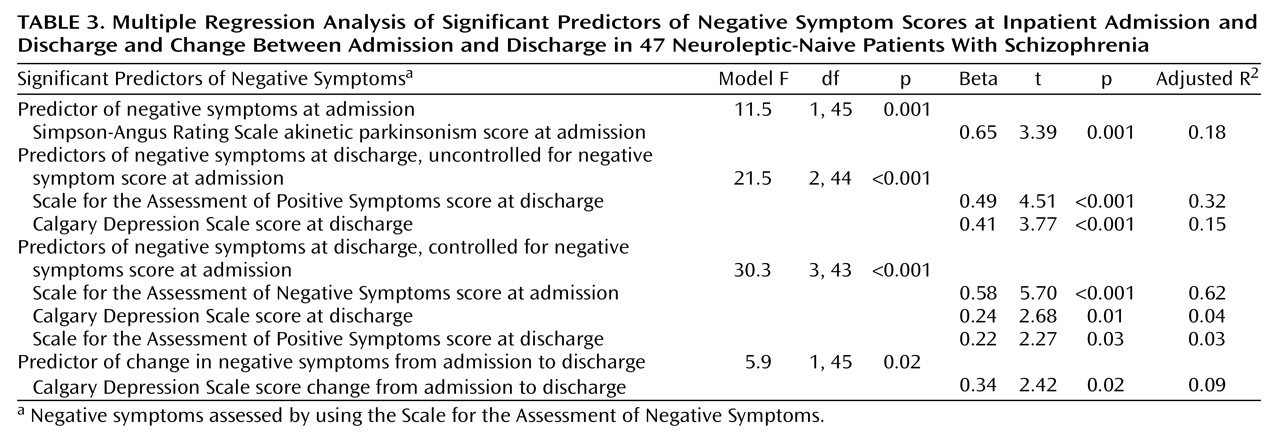

Three separate regression models were constructed for predicting negative symptoms at admission and at discharge and the change in negative symptom scores over the treatment period. Change scores were computed as scores at admission minus scores at discharge. The values for p to enter and to be removed from the regression models were 0.05 and 0.1, respectively. The independent variables included in the models were the two Simpson-Angus Rating Scale ratings, the SAPS total score, and the Calgary Depression Scale total score. We included the two Simpson-Angus Rating Scale scores as negative symptom predictors at admission to examine the overlap between ratings of negative symptoms and the two parkinsonism ratings and to keep the same independent variables across the three separate regression analyses.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine potential secondary sources of negative symptoms such as psychosis, depression, and parkinsonism in a group of neuroleptic-naive psychotic patients before and after neuroleptic treatment. The study design provided us with an unique opportunity to analyze the primary versus secondary nature of negative symptoms by ruling out the effects of chronicity and controlling for the side effects of antipsychotic treatment. The latter case is particularly important, because antipsychotic drugs appear to play a central role in the interrelationships among negative, psychotic, depressive, and extrapyramidal symptoms.

At admission, negative symptoms seemed to be essentially primary in nature, as their variability was not accounted for by ratings of depression or psychosis. The association between negative symptoms and akinesia at this stage is interesting and might reflect either overlapping definitions among constructs or shared pathological mechanisms. The prevalence rate for parkinsonism in this study (19%) is in the range of rates for neuroleptic-naive patients reported by other authors (7–9), providing further support that parkinsonism may be an indigenous feature of schizophrenia. Particularly striking is the similarity between our findings and those of Chatterjee et al.

(8), who used the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale to assess parkinsonism and the SANS to assess negative symptoms. They reported a rate of parkinsonism of 17% and a statistically significant association between parkinsonism and negative symptoms for patients in the neuroleptic-free state.

Change in negative symptoms over the treatment episode did not covary with changes in ratings of psychosis or parkinsonism, but it did covary with ratings of depression, although in a marginally significant way. These findings do not support the proposition of a partial overlap between negative secondary symptoms and positive symptoms during periods of acute psychosis

(17). These findings are also at odds with the findings of some previous studies in which changes in positive and negative symptoms tended to covary in patients receiving antipsychotic treatment

(18,

19); however, other studies have not found this overlap

(5,

20).

At discharge, a substantial proportion of the variance in negative symptoms was explained by positive symptoms and a lesser proportion by depression. This association between positive and negative symptoms can be partly explained by the close association between the disorganization symptoms measured by the SAPS and the negative symptoms, which together formed a single factor (unpublished data of Peralta et al.). If instead of the SAPS total score, a rating of psychosis that included only delusions and hallucinations was introduced in the regression model, it would account for only 8% of the variability in residual negative symptoms (data not shown). The association of depression with negative symptoms at discharge but not at admission is in agreement with previous studies that have suggested that this relationship may be phase-dependent

(4,

21). That residual negative symptoms were mainly primary in nature was corroborated by the finding that negative symptoms at admission (which are supposed to be primary) explained most of the variability in negative symptoms at discharge.

Both in the whole study group and in the subgroup that did not receive biperiden, nonakinetic parkinsonism significantly worsened after neuroleptic treatment, but akinesia did not worsen. These findings suggest that nonakinetic parkinsonism rather than akinetic parkinsonism represents the true side effect of neuroleptic treatment. It is of interest that neither of the two ratings of parkinsonism were meaningful predictors of negative symptoms after treatment was started. This finding could be explained in three ways: 1) most of the patients (39 of 47) were treated with atypical antipsychotics, which produce fewer and less severe extrapyramidal symptoms compared with typical antipsychotics

(22), 2) some patients were administered biperiden because they developed clinically meaningful parkinsonism, and 3) the observation period after starting antipsychotics was too short to detect drug-induced extrapyramidal symptoms, which may not appear for several weeks or even months after starting antipsychotic treatment

(23). In any case, our findings are at odds with the widely accepted view that the presence of akinesia in neuroleptic-treated patients always represents a side effect of medication and a cause of negative symptoms. In addition, the data presented here indicate that antipsychotic treatment during a first psychotic episode does not represent a meaningful source of negative symptoms and furthermore is effective against primary negative symptoms.

The study results must be interpreted in light of a number of limitations. First, one of the major assumptions in regression analysis is the normality of the variables included in the model. This assumption, however, proved not to be realistic for our data, because we could not normalize variables by log transformation. Therefore, these results must be considered with caution. Notwithstanding this limitation, the results of the regression analysis appear to have some validity, because they were consistent with the nonparametric univariate correlational analysis. Second, the assessment period after starting neuroleptic treatment was short; therefore, the findings presented here are limited to patients who were experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia and may not extend to patients who are beyond their initial phase of treatment. Third, we assumed that because the variability in negative symptoms was not explained by drug-induced parkinsonism, depression, or positive symptoms, the negative symptoms were primary in nature. It is possible, however, that the unexplained variance might be due both to error variance associated with unreliability of the symptom ratings and to other sources of negative symptoms that were not controlled for in the analysis. Although the latter possibility cannot be completely disregarded, it seems unlikely because other well-known sources of negative symptoms, namely prolonged institutionalization and chronicity, do not apply to the patients in our study. Fourth, the group size was relatively small and diagnostically heterogeneous. Fifth, patients were assessed by a single rater, and, as a consequence, cross-scale contamination was possible. Last, it has been shown that different groupings of negative symptoms may be differently related to secondary sources

(6). We did not explore the putative predictors of individual negative symptoms because of the small group size, which would have considerably increased the type I statistical error.

In summary, and considering the study’s limitations, the data support the view that negative symptoms, as assessed by using the SANS during a first psychotic episode, represent mainly a primary manifestation of the disorder and thus are closely linked to its basic neurobiological mechanisms. Given that, at this stage of the patients’ illness, negative symptoms improved significantly after neuroleptic treatment, the nature of their neural mechanism is likely to be neurochemical rather than structural

(24), even though the two types of mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. In addition, both the neuroleptic responsiveness of positive and negative symptoms and their lack of covariation over the treatment period suggest the possibility that unrelated neurochemical mechanisms may underlie the two clusters of symptoms.