The relationship between unexplained chronic fatigue and psychiatric disorders is still a controversial issue despite the great research interest

(2). Numerous studies have shown a strong association of unexplained chronic fatigue with general psychiatric morbidity and specific psychiatric disorders, mainly depression

(3). This finding has been reported in studies done in tertiary centers

(4), primary care settings

(5,

6), and the community

(7–

9), and thus it is not due to selection bias

(3). Several explanations have been suggested for this association

(10,

11): 1) it could be due to overlapping criteria for chronic fatigue and psychiatric disorders, especially depression, 2) the association could be causal, i.e., fatigue could be viewed as a neurotic symptom and patients with unexplained chronic fatigue could suffer from a “primary” psychiatric disorder, 3) the psychiatric symptoms could be viewed as a secondary reaction to a chronic physical illness (reverse causality), and 4) confounding could occur if common factors contributed to the etiology of both psychiatric disorders and chronic fatigue.

The majority of the studies that have tried to clarify the relationship between unexplained chronic fatigue and psychiatric disorders have been conducted in tertiary care and have looked for clinical or laboratory differences between patients with chronic fatigue and subjects with psychiatric diagnoses or healthy comparison subjects

(3). Although interesting results have been reported, what has become apparent is that the search for a single cause capable of explaining everything is bound to be unsuccessful

(12). A few studies have been conducted in primary care settings

(6,

10) in response to criticisms that the results of hospital-based studies suffer from serious methodological problems such as selection bias, referral bias, and unclear definitions of chronic fatigue

(13). The findings of these studies showed that although chronic fatigue and psychiatric disorders overlap, they cannot be equated and may have different causes

(3).

The goal of the study reported here is to extend the findings of this research by looking at the relationship between chronic fatigue and psychiatric morbidity in a community sample. This approach is free from the confounding effects of help-seeking behavior and differential access to health care, which are determined by cultural, social, and economic factors

(14). So far, studies in the community have been concerned mainly with estimating the prevalence of chronic fatigue and its basic sociodemographic and psychiatric associations but have not tried to specifically address the complex relationship between fatigue and psychiatric morbidity

(7–

9,

15,

16). For this purpose, we used the data from a 1993 survey of psychiatric morbidity conducted by the Office for Population Censuses and Surveys in Great Britain

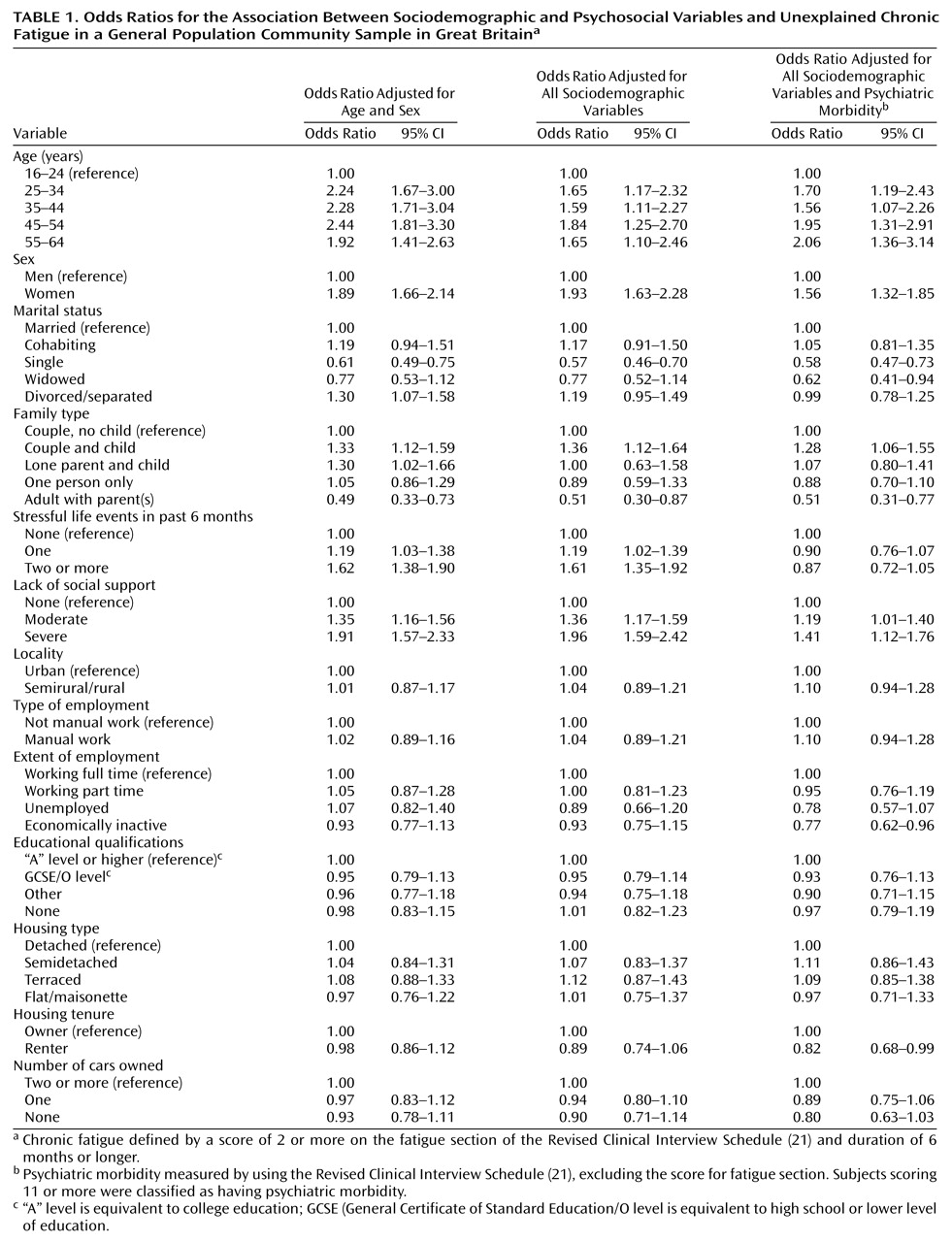

(17). This general population survey gathered data on a large number of sociodemographic and psychosocial variables and measured psychiatric morbidity by using a structured interview. Our main aim was to examine associations between sociodemographic and psychosocial variables and unexplained chronic fatigue before and after the analysis adjusted for psychiatric morbidity. We hypothesized that if chronic fatigue was solely a symptom of the “neurotic spectrum,” then the observed associations would be explained by the presence of psychiatric morbidity. Additional aims were to examine the extent of disability associated with unexplained chronic fatigue and to estimate the prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue in a nationally representative sample of the general population in Great Britain.

Discussion

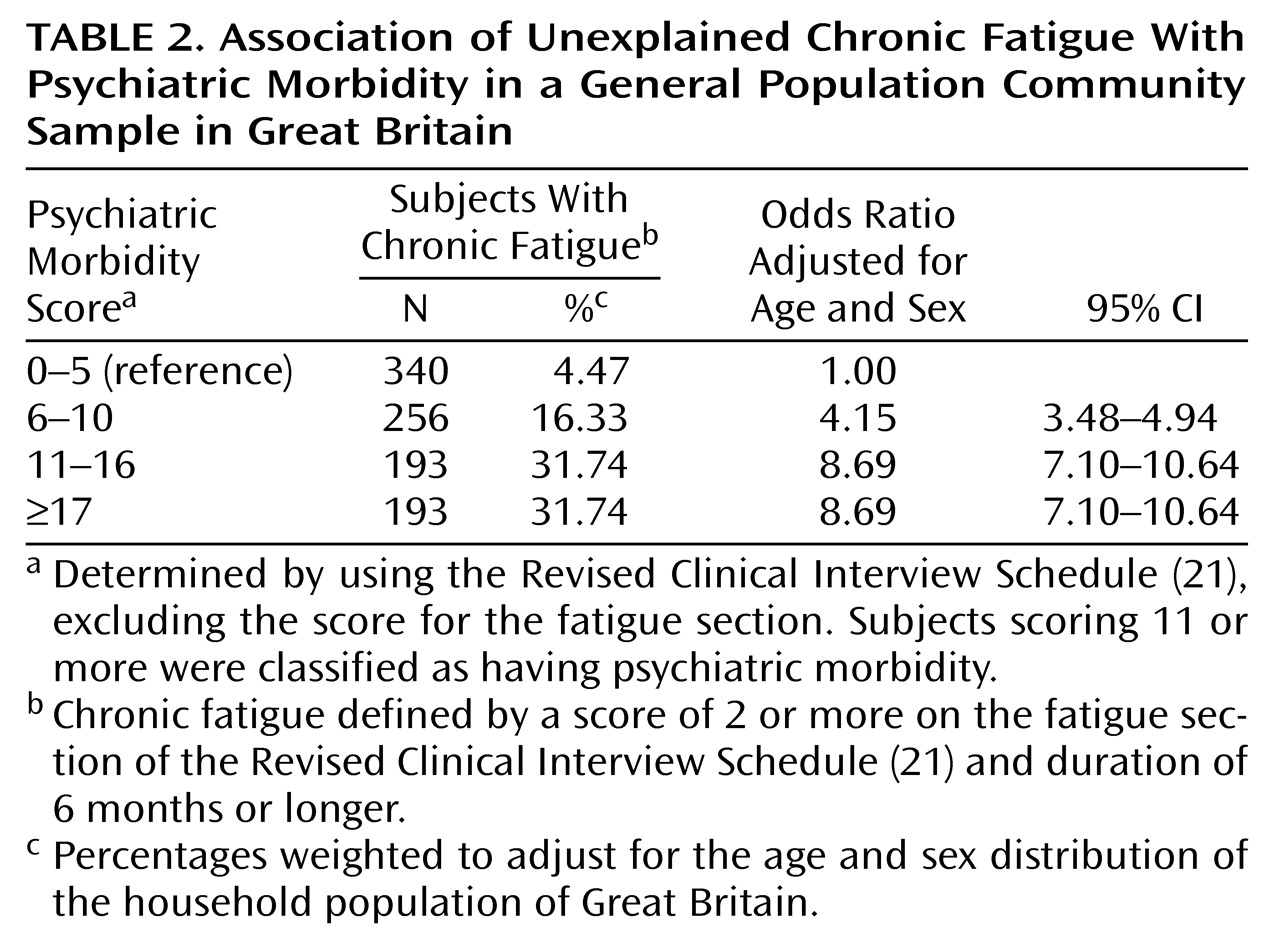

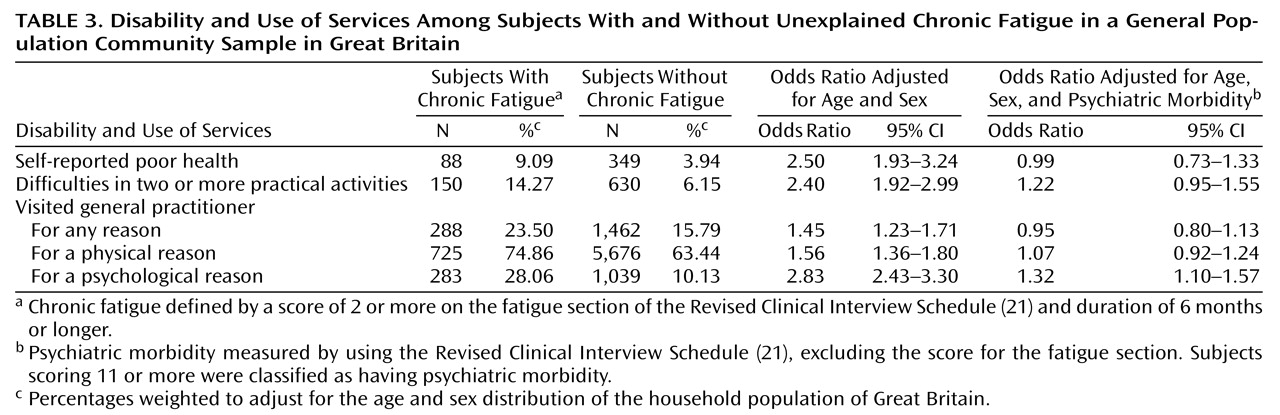

In a general population sample in Great Britain, we found that unexplained chronic fatigue had a point prevalence of 9%. Of primary interest was the finding that the associations between unexplained chronic fatigue and a number of sociodemographic and psychosocial factors were independent of its association with psychiatric morbidity. In addition, although unexplained chronic fatigue was associated with considerable disability and increased health care seeking, this pattern appeared to be due to the association between unexplained chronic fatigue and psychiatric disorder.

The findings should be considered in the context of some limitations. First, the study was a secondary analysis of a data set collected for other purposes. We measured fatigue by using the questions about this symptom included in the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule. This set of questions was not developed to be used as an independent scale for measuring fatigue, although the questions have been used by other researchers for comparison purposes in their development of a fatigue scale

(23). Second, our approximation of the prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue relied on excluding subjects with self-reports of long-standing illness that can cause fatigue, and the reports may be inaccurate. We may have overestimated the prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue because we may have classified subjects with short-term illnesses that can cause fatigue as having unexplained chronic fatigue. Alternatively, we may have excluded subjects with unexplained chronic fatigue who are permanently sick because of their longstanding fatiguing illness. These misclassifications, if they were random, would not threaten the validity of our results; in the case of overascertainment, the misclassification would tend to reduce the measure of the association between fatigue and other factors, and in the case of underascertainment, it would leave the measure of the association unaffected

(24). However, a systematic bias could also have been introduced.

Studies in many settings have found a strong association between psychiatric morbidity and chronic fatigue. The odds ratio of 4.9 (95% CI=4.2–5.7) that we found for this association is comparable with odds ratios found in other studies both in the community and in primary care settings

(6,

7). Although the association of chronic fatigue with psychiatric morbidity appears very strong, we also found that various other factors are independently associated with chronic fatigue in the community. We studied a number of sociodemographic and psychosocial variables, and we found a higher prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue in older age groups, women, couples with children, and those with severe lack of social support. In contrast, the prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue was lower in single subjects, widowed subjects, adults living with their parents, and economically inactive subjects. Although the possibility of type I errors has to be considered, the pattern of results is not consistent with random error.

The prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue has not been systematically investigated in other community studies in the United Kingdom, although a few studies have reported that the point prevalence of chronic fatigue of any cause ranges from 14% to 18%

(7,

8). In the United States, Walker et al.

(9), using data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, reported that the 1-month prevalence of unexplained fatigue lasting longer than 2 weeks was 6%. Buchwald et al.

(16), in a study of members of a single health maintenance organization, found a point prevalence of unexplained chronic fatigue of 6.6%. These figures are quite similar to ours, given the different criteria and instruments used and the different populations studied.

Women were more likely to report unexplained chronic fatigue, even after the analysis adjusted for psychiatric morbidity. This finding is in line with findings in other community or primary care studies

(8,

25), although the odds ratios we found are slightly higher. We also found that having no children, living with parents, and not working are associated with reduced rates of fatigue. These findings offer a perspective on the social circumstances that may influence the onset or maintenance of fatigue. Fewer responsibilities in everyday life may protect from chronic fatigue, and working harder and having more responsibilities may increase the risk for fatigue.

Unexplained chronic fatigue was associated with considerable disability. Subjects with fatigue had a worse perception of their health and were more likely to restrict their daily activities, compared with those without chronic fatigue. They also tended to visit a general practitioner more frequently. These findings confirm those of other studies in primary care settings

(5,

25). However, our analysis suggested that the excess of disability was largely explained by psychiatric morbidity, because the association became nonsignificant after the analysis adjusted for psychiatric morbidity. These findings extend similar findings reported both in primary and tertiary care. Wessely et al.

(25) reported a close association between functional impairment and psychiatric morbidity in subjects with chronic fatigue in a primary care setting. In a study in a tertiary care setting, Russo et al.

(26) showed that improvement in psychological symptoms was associated with improvement in the functioning of chronic fatigue patients. This link between functional impairment and psychiatric morbidity was also noted in a World Health Organization study of psychological problems in primary care settings

(27); that study used the ICD-10 diagnosis of neurasthenia, which is very similar to unexplained chronic fatigue. In contrast, Komaroff et al.

(28), in their tertiary care study, reported that chronic fatigue syndrome patients with depression and those without depression had similar profiles of functional impairment, perhaps reflecting the highly selected study population. It is interesting to note that the association of psychological morbidity with disability and health care seeking is not specific to fatigue but has also been shown in other common conditions of functional origin, such as irritable bowel syndrome

(29), headache (association with a history of panic disorder)

(30), and tinnitus (association with affective disorder)

(31).

How can one interpret these findings? Our analysis of a cross-sectional study is certainly limited in attempting to draw specific conclusions about etiology or the presence of specific risk factors. However, the purpose of our study was to compare the pattern of associations for unexplained chronic fatigue and psychiatric morbidity. Our results suggest that fatigue does have a different pattern of associations, once the association between fatigue and psychiatric morbidity has been taken into account. Thus, even if there is a causal relationship between psychiatric morbidity and fatigue, there are also other factors that are likely to be important.

Certain practical implications arise from our study. First, our findings support the view expressed by other researchers that a multifactorial model of fatigue states, which takes into account biological, psychological, and social factors, offers a better understanding of these complaints

(32,

33). In practice, the assessment of fatigued patients should include not only symptoms, either physical or mental, but also beliefs, coping behaviors, and interpersonal and occupational problems, as has been proposed by Sharpe and his colleagues

(34). Second, since disability is largely explained by the presence of psychiatric morbidity, the careful assessment and management of the latter could reduce the functional impairment of individual patients

(35).

In conclusion, unexplained chronic fatigue is a common disabling condition in the general population and is strongly associated with psychiatric morbidity. However, the close relationship between fatigue and psychiatric morbidity should not obscure the possibility that there may be differences as well as similarities in their etiologies.