To the Editor:

As Michael Davidson, M.D., and colleagues

(1) pointed out, identifying individuals premorbidly who will later develop schizophrenia offers the prospect of early intervention, the hope of a reduced risk of dangerous behaviors and hospitalization, and the possibility of improved prognosis and better treatment response. The authors presented a potentially important set of factors that, when combined, yield high sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value for identifying individuals at high risk for schizophrenia from a general population.

A serious difficulty in the development of a screening tool for schizophrenia in the general population is posed by false positives. Incorrectly identifying an individual as “at risk” may have adverse consequences, including unwarranted stigmatization, a negative impact on eligibility to obtain health care insurance or to pursue other opportunities, unnecessary anxiety and worry for the individual and his or her family, and the avoidance of age-appropriate challenges

(2). Caution must thus be exercised in applying screening methods for a disorder with low incidence, because even with high specificity, more individuals identified by a screening test as “at risk” will be false positive than true positive.

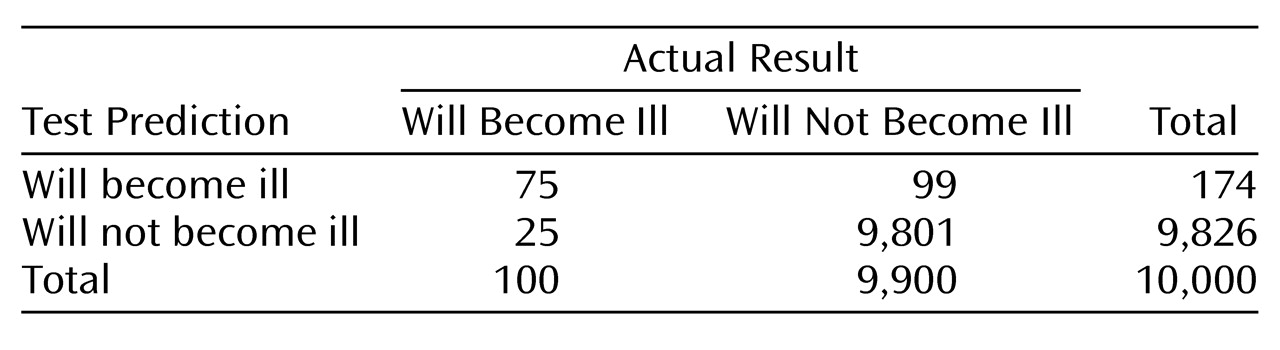

This two-by-two

table describes a hypothetical general population of 10,000 individuals. Assume that 1% will develop schizophrenia and that the screening test for schizophrenia has a specificity of 99% and a sensitivity of 75%.

In this example, the screening test identified 174 individuals as at risk for illness; 75 (43%) are correctly classified, and 99 (57%) are incorrectly classified. Thus, even with high specificity, more individuals identified by the screening test are false positive than true positive. Furthermore, as specificity decreases, the proportion that are false positive rapidly increases. For example, if the specificity were 90%, then the screening test would identify 1,065 individuals as at risk, 990 (93%) of whom would be false positive. Dr. Davidson and colleagues reported a “validated specificity” of 99.7% for their screening tool. Sensitivity and specificity are not absolute values but vary with cutoff scores. Measurement error and other factors make it unlikely that the screening tool would have perfect or near-perfect specificity when used to screen for schizophrenia in other populations. Even with near-perfect specificity (99.7%), the test predicted that 103 individuals would become ill, of whom 30 individuals (29%) were false positive.

The authors concluded that the screening tool can predict predisposition to schizophrenia and “identifies apparently healthy individuals who will manifest the disease later who are not prodromal to psychosis.” I suggest that care should be exercised in applying any screening strategy for schizophrenia to a general population, given the problem posed by false positives and the potential harm that could result from falsely identifying a healthy individual as at risk for the devastating consequences of schizophrenia. Instead, sequential screening strategies may be valuable, where initial screening identifies high-risk individuals who may then participate in more definitive diagnostic evaluation

(3).