Summary of Findings

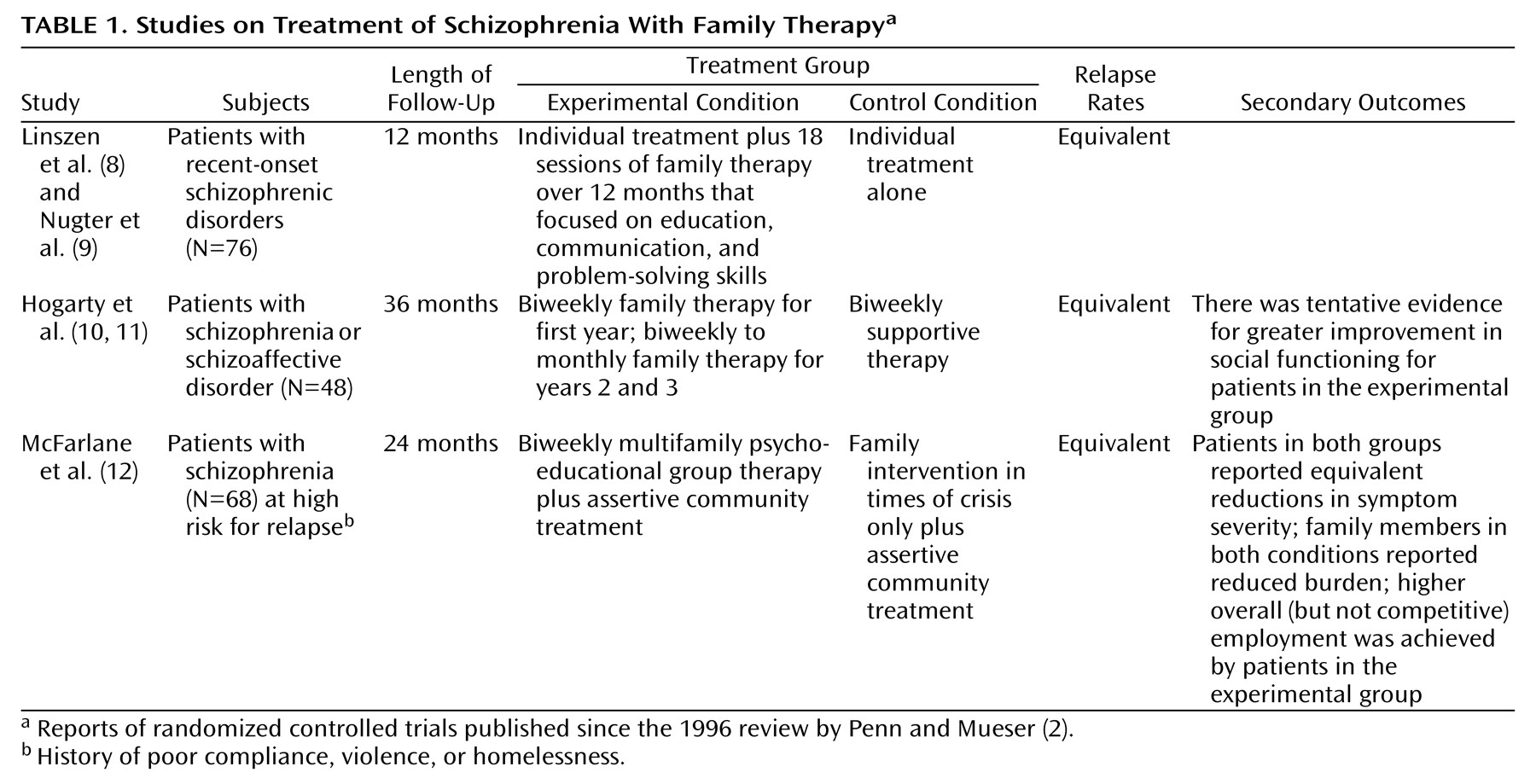

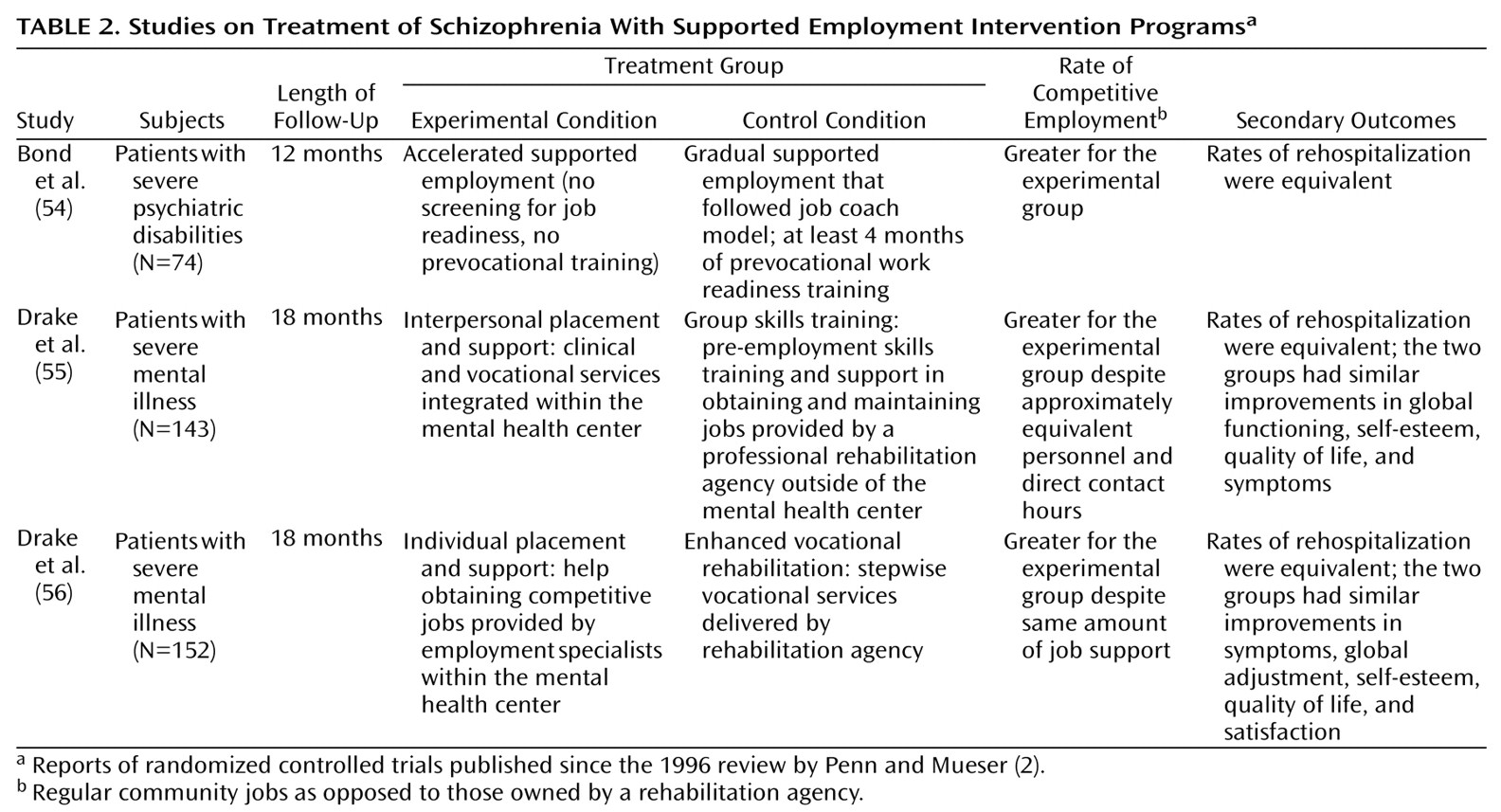

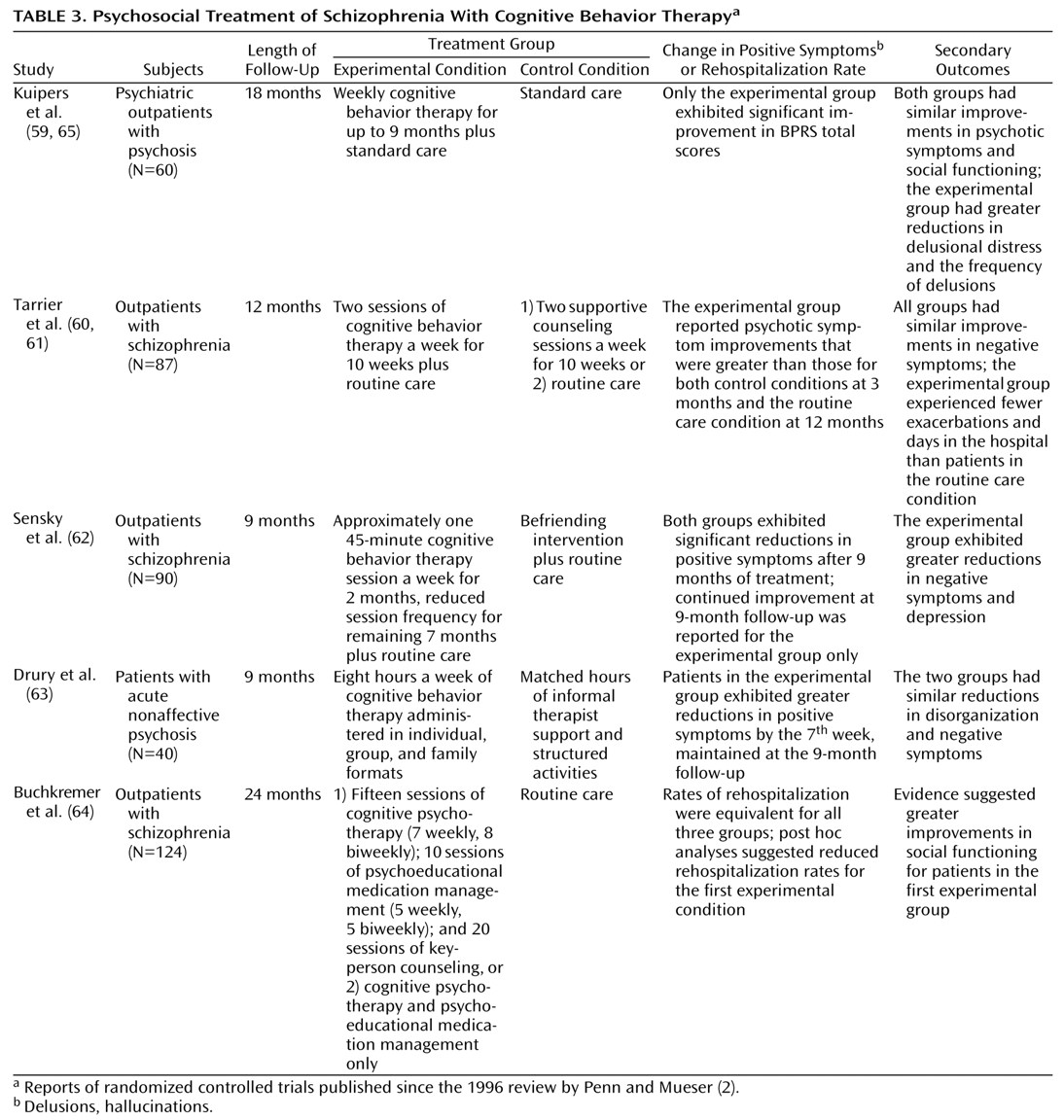

Over the last 4 years, research on psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia has continued to develop. We reviewed randomized controlled trials with a special emphasis on those published since the last update by Penn and Mueser

(2). For the more extensively studied interventions (family therapy and assertive community treatment), the recent studies have had largely negative findings

(8–

10,

12,

33,

34). In our view, this does not so much put in doubt the large body of research supporting the efficacy of these treatments but rather is consistent with the level of evolution of research into these modalities. These findings reflect more sophisticated studies of either special populations (e.g., patients very early in their illness [

8,

9]) or inclusion of enriched packages of care as control conditions

(10,

12,

33,

34). In contrast, studies of two relatively new modalities, supported employment programs

(54,

56) and cognitive behavior therapy

(59–

64), have shown mostly positive findings. Also, the few social skills training studies of interventions designed to increase generalization of skills (the social problem-solving [

45,

46] and cognitive remediation models

[50]) have reported promising results.

On the whole, the literature is consistent in that the various interventions have been largely successful for the primary outcome measures they were designed to target (i.e., family therapy and assertive community treatment for prevention of psychotic relapse and rehospitalization, social skills training for learning specific social behaviors, supported employment programs for obtaining competitive employment, and cognitive behavior therapy for reducing delusions and hallucinations). However, these effects tend to be domain specific and do not result in improvements in other clinically important secondary outcomes. For some interventions, this lack of an effect on other measures is not a serious limitation. With supported employment programs, attainment of competitive employment is clearly worthwhile, regardless of a limited effect on social adjustment or psychopathology. Likewise, with cognitive behavior therapy, reduction in the distress associated with psychotic symptoms is a highly desirable outcome, especially when other available treatments have failed. However, for the social skills training modalities, even if learning of skills is robust in most patients and can be maintained over time with relatively few resources, demonstrating some degree of generalizability and improved community functioning is crucial. Direct demonstration of use of learned skills in the community is a daunting methodological challenge yet to be accomplished.

The identification of “active ingredients” for different interventions has had very limited success. Beyond the general advantage of sustained over brief interventions in terms of primary outcomes, little is known regarding the specificity of the various treatments. Even for family interventions, the construct of “expressed emotion” has not been clearly shown to underlie the efficacy for relapse prevention. Also, when two forms of family interventions are compared, the literature is consistent that no advantages are evident. Similarly, recent studies of assertive community treatment suggest that “more is not necessarily better” and that for many patients, even those with high relapse rates, high-quality clinical case management with adequate service availability is equally effective. Because the effects of these interventions are mainly on relapse prevention, in populations of patients in which the base rate of relapse is already low (such as medication compliant persons early in their illness), there may be no advantage of adding family therapy, as the most recent studies suggest. With novel antipsychotic medications becoming the standard of care, compliance will hopefully improve, and relapse rates may be lowered; this could result in the amelioration of the effects of family treatment and assertive community treatment programs on relapse.

Transferability of efficacious treatments to more usual clinical settings has been documented for only a minority of interventions (like assertive community treatment and perhaps the social skills training problem-solving model). Cost-effectiveness has been documented for assertive community treatment when compared to usual community care but not when compared to another high-resource model of clinical case management.

Future Research

For the newer interventions such as supported employment programs, cognitive behavior therapy, cognitive remediation, and personal therapy, replication of the initial positive findings is necessary in large samples, in different settings, and by investigators not directly involved in the development of these treatment modalities. For family interventions and assertive community treatment, future research should concentrate on 1) identifying the minimal intensity of services that will maintain the relapse-preventing effects and 2) examining whether some subgroups of patients may benefit in particular. In the services research arena, it is necessary to demonstrate whether assertive community treatment programs effective in the community result in cost savings. Likewise, studies are needed of the cost-effectiveness of sustained psychoeducational family interventions added to adequate standard care.

Since effective interventions tend to be domain specific, it is important to investigate when to apply particular treatments. Because the majority of patients will relapse, sustain deficits in social competence, and fail to attain competitive employment (and many will experience persistent psychosis), research is needed to guide the optimum sequencing and combination of specific services to be delivered. For example, should social skills training precede, follow, or be implemented concurrently with cognitive behavior therapy in patients with persistent psychosis and limited social skills? And for what subgroups of patients and at what stage of the illness should a particular intervention be implemented?

For the supported employment approach, future studies should address the issue of the extent of ongoing support required to maintain efficacy and changes in the social security disability system such as retention of benefits despite competitive employment that might foster these vocational gains.

Finally, because of the continued development of newer and hopefully better antipsychotic agents, the interactions between different psychosocial and pharmacological modalities should be investigated. We are aware of only two

(20,

45) randomized trials that controlled the psychosocial as well as the pharmacological intervention (neither involved novel antipsychotic agents). One study

(45) found an interaction between psychosocial and pharmacological treatments, which suggested that the problem-solving social skills training approach may provide protection against relapse among patients suboptimally medicated. The other study

(20) found no interaction between two forms of family treatment and three antipsychotic medication dose regimens.

Clinical Recommendations

What implications can be drawn for the use of the psychosocial interventions described in this review, for the standard of care for persons suffering from schizophrenia? For frequent relapsers who reside with family, a relatively simple but sustained psychoeducational family approach should be offered (for example, monthly visits in a single or multifamily group setting). Additionally, for the majority of patients, the family should be viewed as a natural ally that can provide crucial early information regarding relapse, substance abuse, community functioning, and compliance. For patients with high service utilization rates, assertive community treatment programs should be considered, especially if family involvement is not available. With the large majority of schizophrenia patients living in the community and hospital stays becoming progressively shorter as a result of managed care, a comprehensive system of delivery of services based on assertive community treatment principles will continue to be necessary for a large proportion of patients.

Once stable community living is achieved, a systematic rehabilitation effort for the majority of persons with schizophrenia is necessary. Beyond allowing patients to make use of previously learned social skills once the psychotic process is sufficiently controlled, there is no compelling evidence that medications (even the novel drugs) offer additional benefits in terms of social competence

(1). Specific strategies to teach social skills are available. Of these, the social problem-solving model not only has resulted in the acquisition of skills but also is the approach with some evidence that suggests generalization of skills to community functioning and of effectiveness in more routine clinical settings. The requirement of social skills training for clinicians specifically trained in these techniques presently limits their use, but the availability of printed manuals with well-defined modules targeting different areas of social functioning is a fundamental step towards disseminating these interventions.

Patients who wish to work should be referred to a vocational rehabilitation agency with resources for supported employment. No other psychosocial or pharmacological treatment has been shown to promote competitive employment. However, for many patients a traditional sheltered form of employment or no employment will remain the best option. Because presently there is no evidence to identify these patients in advance, the majority of persons suffering from schizophrenia should be offered the supported employment approach when available.

A large number of patients will continue to experience disturbing delusions and hallucinations despite the best available medications. Persistent symptoms after an adequate trial with one antipsychotic agent generally predict little response to other medications. Superiority for previously resistant psychotic symptoms has been demonstrated only for clozapine

(1), but a recent meta-analysis of efficacy for this agent suggests that the effects, although important, are smaller than originally found

(70). Therefore, the results from cognitive behavior therapy interventions are particularly encouraging. Currently, these strategies are in their infancy, there are few clinicians with the expertise to implement them, and it is not clear that even in the best hands these strategies will result in clinically meaningful sustained effects. Nevertheless, cognitive behavior therapy has become established for the treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders and may prove to be a valuable resource for clinicians helping persons with chronic psychotic disorders as well.