Previous research that compared psychiatrists with other physicians found that psychiatrists hold more empathic attitudes about depression and are more confident in their ability to treat it

(1) and are more likely to prescribe antidepressant medication

(2). However, there are still many unanswered questions about other differences between psychiatrists and other physicians such as differences within gender.

Women are becoming a notably greater part of the psychiatric workforce. Data from the National Survey of Psychiatric Practice indicate that the percentage of psychiatrists who are women rose sharply from 14.5% in 1982 to 25.0% in 1996

(3). Relative to their male peers, female psychiatrists are younger

(4,

5), work fewer hours

(4), spend a greater proportion of their time in public and private clinics and outpatient facilities

(5), and have lower mean annual incomes

(4). Research examining clinical practice characteristics has found that female psychiatrists are less likely than their male counterparts to be in practices in which medications are prescribed to a large proportion (>85%) of their patients

(6) and are also less likely to perform ECT

(7).

Physician characteristics are important predictors of patient outcomes

(8) and physician health. While previous research has suggested a higher prevalence of benzodiazepine use

(9), other substance use

(10), and suicide among psychiatrists

(11), there have been few studies of personal health choices or other characteristics of either female or male psychiatrists.

Moreover, as physicians, psychiatrists may have an important role in counseling patients regarding preventive health care, particularly since psychiatric patients commonly present with medical comorbidities

(12,

13) and may see their psychiatrists more frequently than other physicians. While previous research suggests that female physicians provide more preventive health care services than men

(14), that prior observation was restricted to a sample of primary care physicians that did not include psychiatrists. To better address these issues, we examined an array of demographic, clinical, personal health variables, and preventive health care counseling practices in psychiatrists and other physicians by using data taken from a large national sample of U.S. female physicians.

Method

The design and methods of the Women Physicians’ Health Study have been more fully described elsewhere, as have the basic characteristics of the population

(15–

17). In 1993–1994, the Women Physicians’ Health Study surveyed a stratified random sample of U.S. women M.D.’s; the sampling frame was based on the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterfile, a database intended to record all M.D.’s residing in the United States and its possessions. Using a sampling scheme stratified by decade of graduation from medical school, we randomly selected 2,500 women from each of the last four decades’ graduating classes (1950 through 1989). We oversampled older female physicians, a population that would otherwise have been sparsely represented by proportional allocation because of the increase in the number of female physicians in recent years. We included active, part-time, professionally inactive, and retired physicians, age 30–70 years, who were not in residency training programs in September 1993, when the sampling frame was constructed. In that month, the first of four mailings was sent out; each mailing contained a cover letter and a self-administered four-page questionnaire. Enrollment was closed in October 1994 (final number of respondents=4,501).

Of the potential respondents, an estimated 23% were ineligible to participate because their addresses were wrong, they were men, or they were deceased, living out of the country, or were interns or residents. Of female physicians eligible to participate, the response rate was 59%. We compared respondents and nonrespondents in three ways. We conducted a phone survey of 200 randomly selected nonrespondents and compared their telephone responses to the written responses of all who returned the survey. We also used the AMA Physician Masterfile to contrast respondents and nonrespondents. Last, we examined each of the four survey mailing waves to compare respondents and nonrespondents with regard to a large number of key variables. From these three investigations, we found that nonrespondents were less likely than respondents to be board-certified. However, respondents and nonrespondents did not consistently or substantively differ on other tested measures, including age, ethnicity, marital status, number of children, alcohol consumption, fat intake, exercise, smoking status, hours worked per week, frequency of being a primary care practitioner, personal income, or percentage actively practicing medicine.

On the basis of these findings, we weighted the data by decade of graduation (to adjust for our stratified sampling scheme) and by decade-specific response rate and board certification status (to adjust for our identified response bias). The analysis weights for board-certified and non-board-certified respondents, respectively, by decade were as follows: 3.4 and 5.5 (1950s), 9.3 and 17.7 (1960s), 17.9 and 36.5 (1970s), and 28.3 and 63.9 (1980s). Using these weights allowed us to make inference to the entire population of female physicians who graduated from medical school between 1950 and 1989.

All analyses were performed using SUDAAN, a specialized software for analysis of complex sample survey data. SUDAAN not only performs weighted analyses but also accounts for the sampling design (i.e., stratification) when calculating standard errors and performing statistical tests. Thus, the proportions, medians, and means presented in the tables that follow are population estimates, and standard errors (SE) rather than standard deviations are included in the tables. For differences in characteristics between psychiatrists and the other female physicians, the level of significance was set at p<0.01 because of the multiple testing.

Results

Personal Characteristics

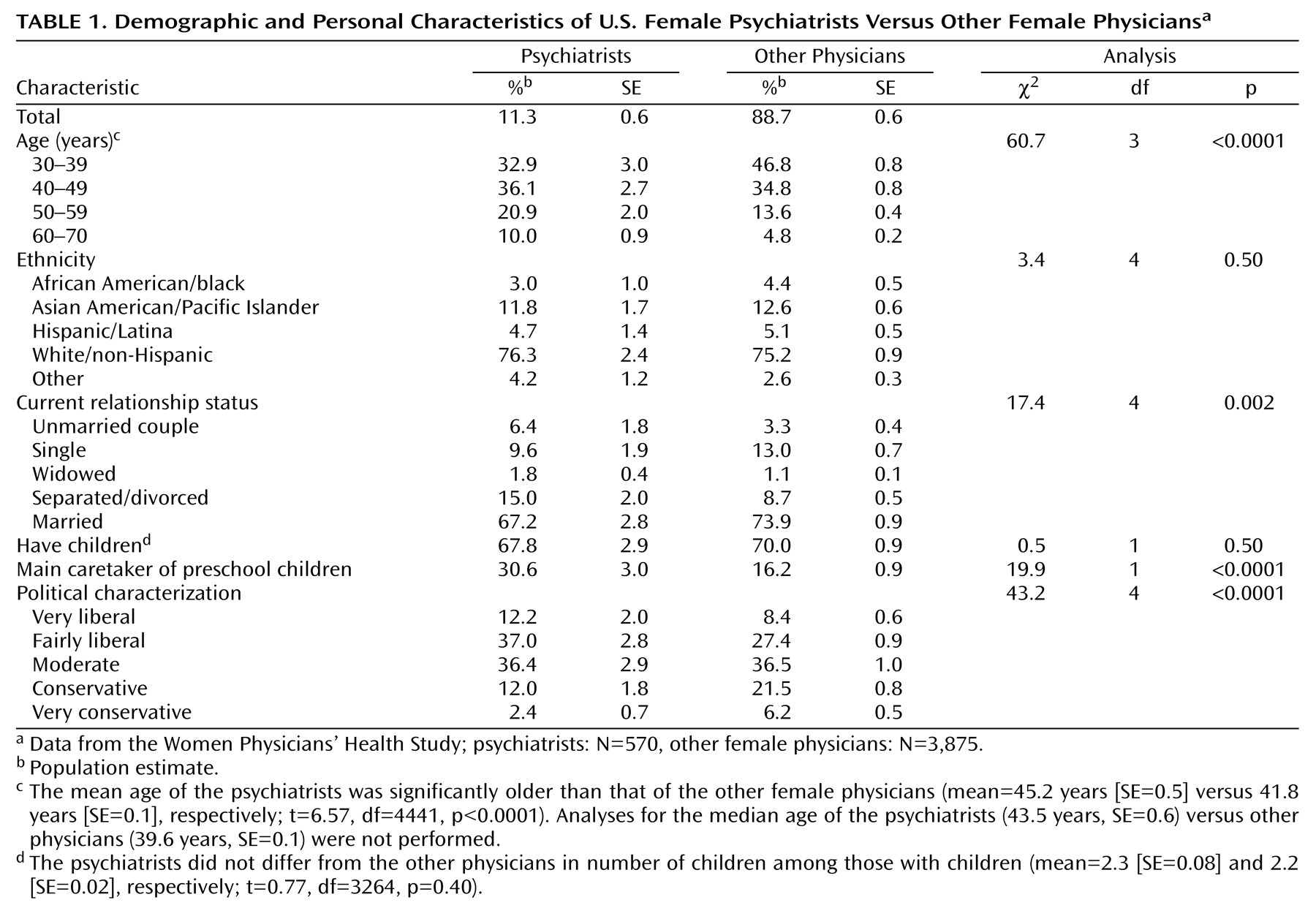

Psychiatrists were significantly older than the other female physicians and were also less likely to be married (

Table 1). Higher percentages of psychiatrists characterized themselves as politically liberal, and higher percentages reported being the primary caretaker of their preschool children. Their birthplace, ethnicity, partners’ educational levels, levels of stress at home, and the percentage with children were similar to those of the other female physicians (not all data shown).

Personal Health and Health Habits

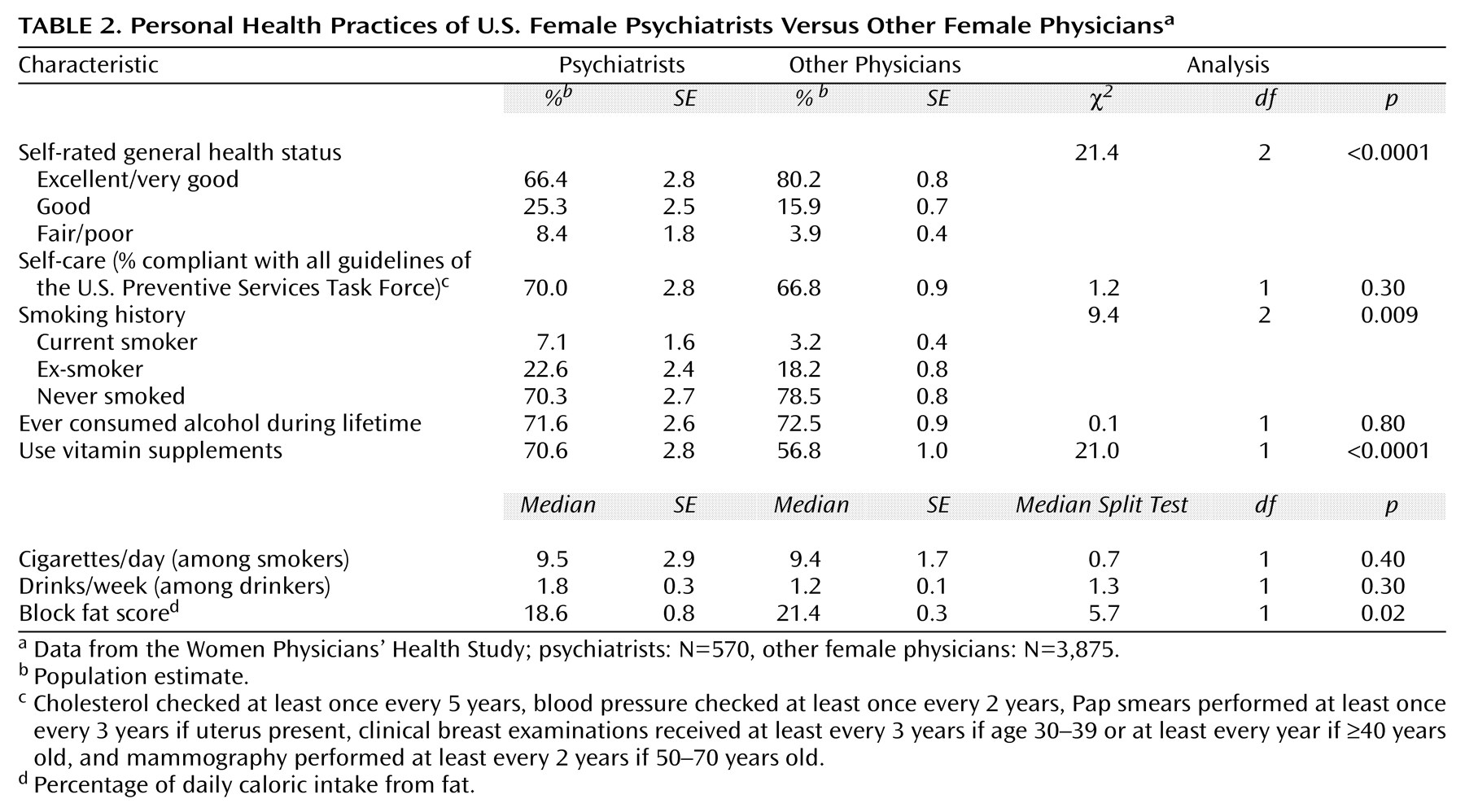

Psychiatrists were more likely to report poorer health than were the other female physicians (

Table 2); this was true even when data were age-adjusted. They were more likely to be current or ex-smokers but consumed somewhat less fat and were more likely to take vitamin supplements. The personal health behaviors of psychiatrists were not otherwise significantly different from the other female physicians. They were not significantly more likely to consume more fruits and vegetables or to exercise more (data not shown), to drink alcohol or to drink more alcohol if they were drinkers, or to comply with examined U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations

(18).

Training- and Practice-Related Characteristics

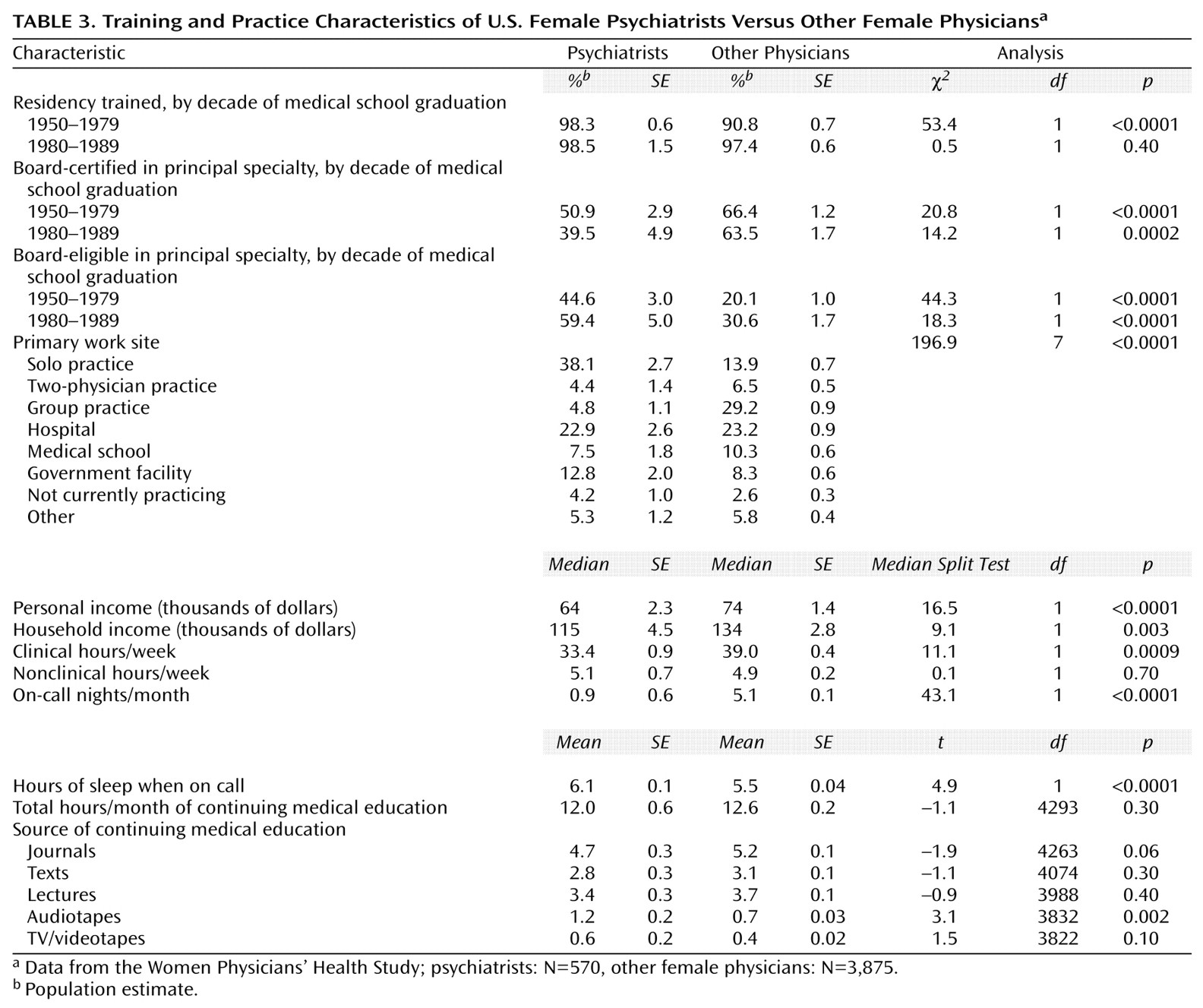

Psychiatrists who graduated from medical school in the 1950s–1970s and in the 1980s were less likely to be board-certified than were the other female physicians, although most of those who were not board-certified were board-eligible (

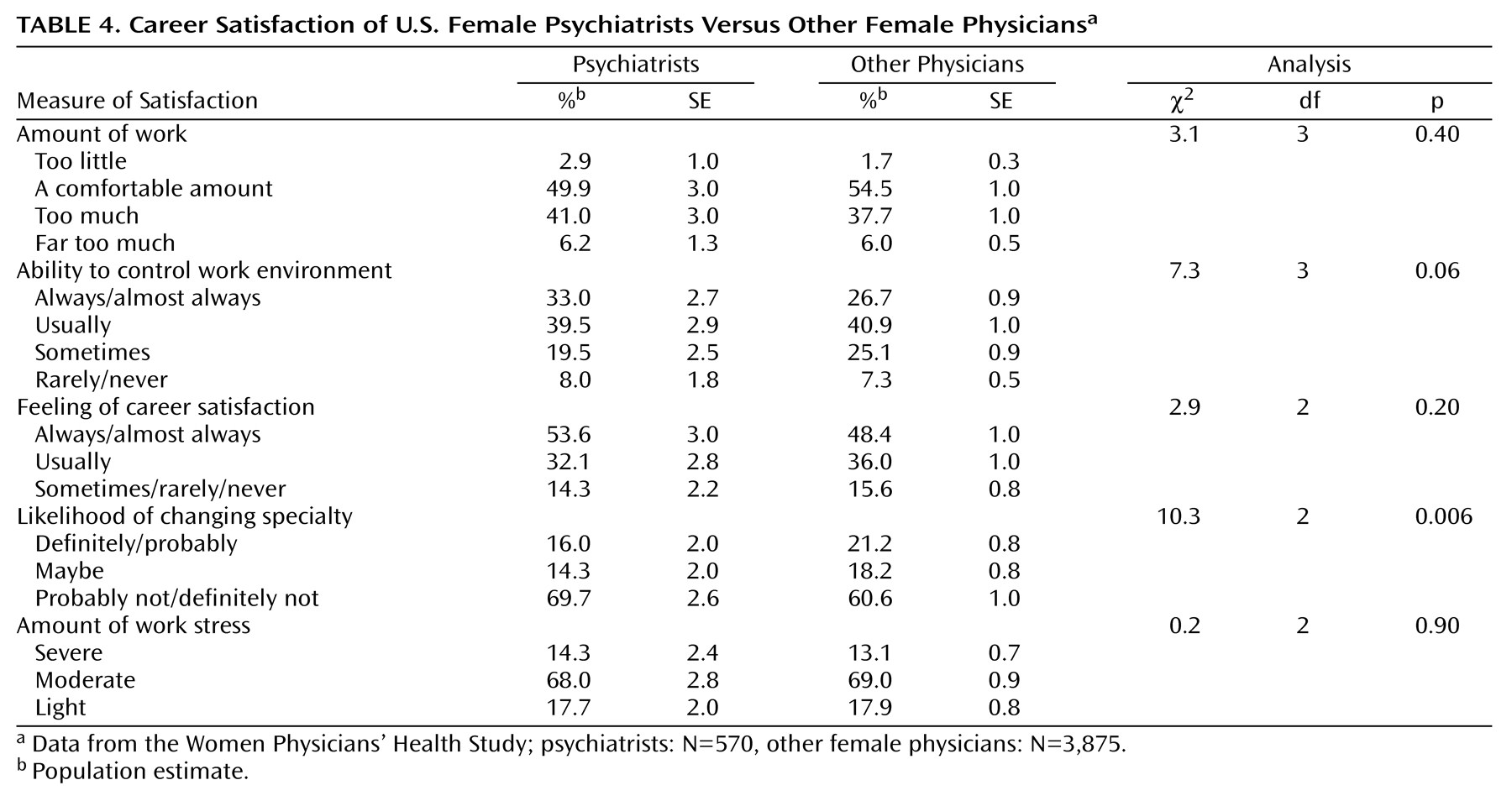

Table 3). Nearly all psychiatrists who were board-certified in another specialty were also board-certified in psychiatry (not shown). Psychiatrists were more likely to have a solo practice and less likely to be in a group practice than were the other female physicians. They were more likely to use audiotapes for continuing medical education. Psychiatrists reported lower personal and household incomes than did the other female physicians. However, they also worked fewer hours and had comparable hourly incomes (not shown). Psychiatrists also had fewer call nights than did the other female physicians, and they slept more when on call. Despite their fewer work hours and greater likelihood to be solo practitioners, psychiatrists did not differ from the other female physicians in perceived work amount, work stress, work control, or career satisfaction (

Table 4). Their satisfaction with their specialty was, however, greater than that of the other female physicians.

Psychiatric Histories as Predictors of Specialty

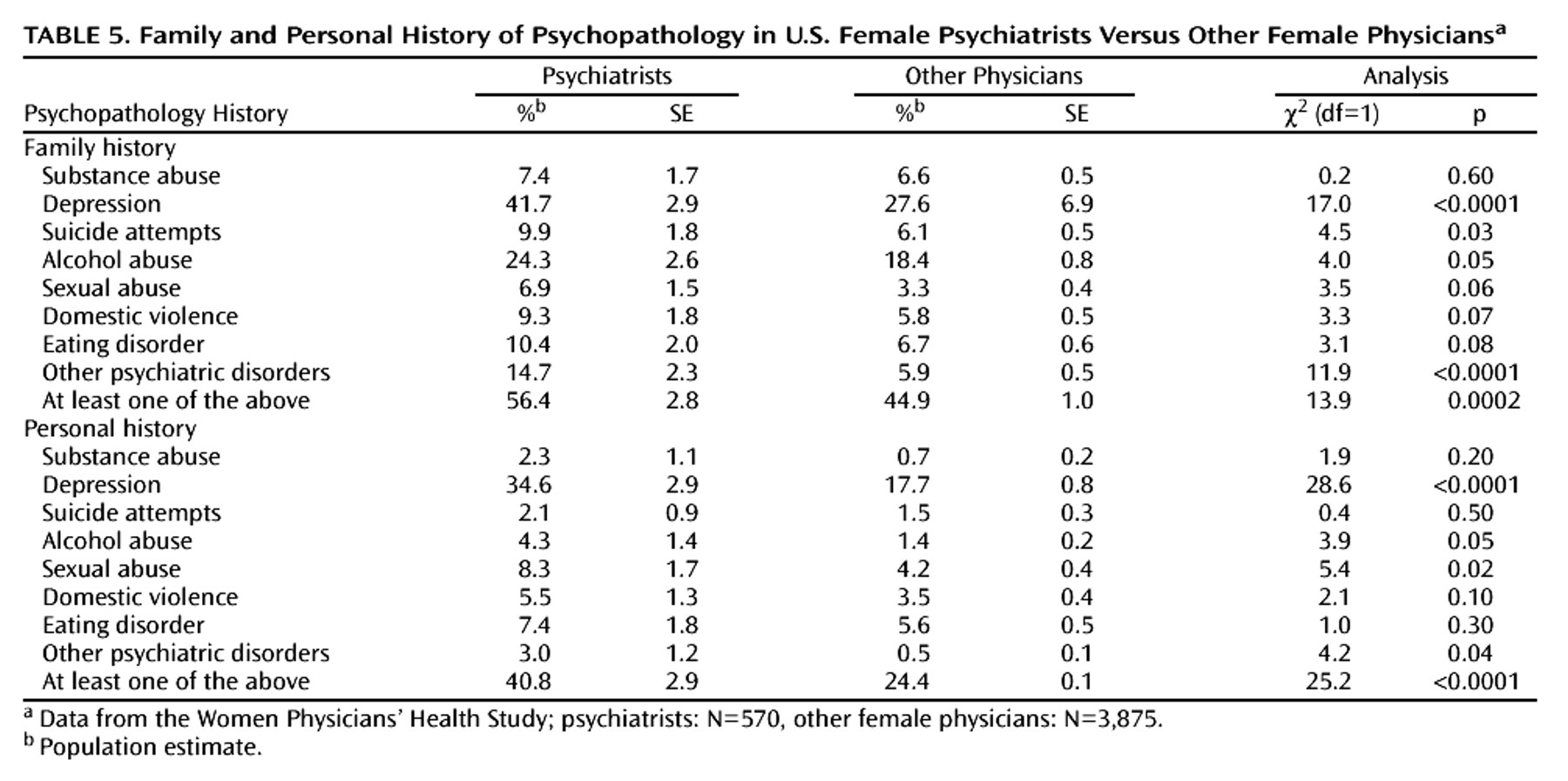

We wished to determine if personal or family histories of psychiatric disorders predicted choosing a psychiatric specialty. Psychiatrists were somewhat more likely than the other female physicians to report a personal history of depression, alcohol abuse, sexual abuse, or another psychiatric disorder (

Table 5). Psychiatrists were also somewhat more likely to report a family history of depression, suicide attempts, alcohol abuse, or another psychiatric disorder and were marginally more likely to report family histories of sexual abuse, domestic violence, or eating disorders. They were more likely than the other female physicians to have a personal and family history of at least one of the listed conditions. However, differences in personal and family psychopathology were statistically significant only where the sample size was large, e.g., in the case of depression.

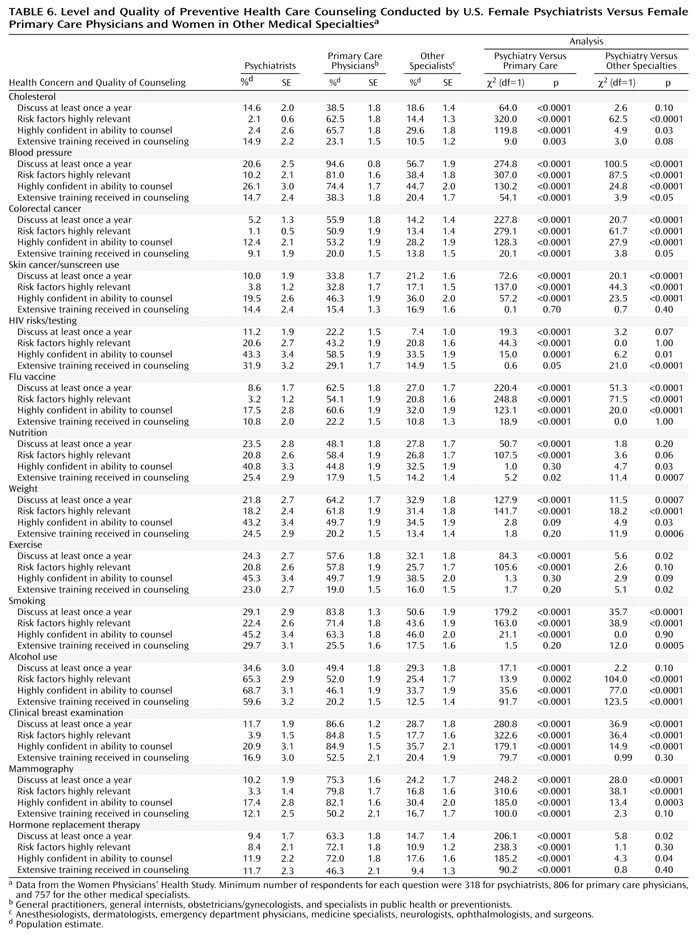

Patient Counseling Practices

For nearly all the 14 prevention-related counseling practices examined, the amount of counseling psychiatrists reported performing, the clinical relevance they ascribed to those practices, their self-confidence in performing the practices, and the amount of training they reported receiving was significantly lower than that of primary care practitioners and lower than or comparable to that of other specialists (

Table 6). Of these four outcomes, psychiatrists differed least often from the other female physicians in the amount of training received.

Discussion

Although there have been some investigations into the incidence of psychiatric disorders among female physicians

(19,

20), this study is the first to our knowledge to compare female psychiatrists to other female physicians with respect to their personal characteristics, personal health habits, and practice-related issues. Despite great interest in the psychiatrically impaired psychiatrist

(21), there has been little prior systematic research on the incidence of psychiatric illness or other characteristics of this population versus that of other physicians.

Psychiatrists in this study were more politically liberal and were older than the other female physicians. Both these phenomena may be related to an earlier acceptance of women into psychiatry versus some other medical specialties.

Historically, it has been proposed that many practitioners enter psychiatry to address their own problems and conflicts

(22). Our study indicates that psychiatrists are more likely than other female physicians to have a personal or family history of psychiatric illness, which suggests that such histories might contribute to choosing a psychiatric specialty. Alternatively, higher levels of reported personal or family history of psychiatric illness among female psychiatrists may result because psychiatrists are better able to identify these conditions or are more open to psychiatric diagnoses than other physicians. Moreover, a personal or family history of psychiatric illness may heighten psychiatrists’ awareness of the impact of psychiatric disorders and facilitate empathy with patients. However, these interspecialty mental health differences were only statistically significant for depression.

We found that major opportunities remain for psychiatrists to address preventive health measures with their patients. Psychiatrists are particularly well-suited to discuss anxieties

(23) and misperceptions that may limit patient adherence to preventive health care practices. Integration of appropriate preventive health care counseling with the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders embodies the biopsychosocial perspective

(24,

25) of contemporary psychiatry.

Psychiatrists were less likely to counsel patients about alcohol abuse than were primary care physicians and less likely to counsel on smoking cessation than were either other specialists or primary care physicians despite having received equivalent or more training in these areas. This is an important missed opportunity for psychiatrists, since both depressive disorders

(26) and schizophrenia

(27) are associated with high rates of cigarette smoking. Moreover, one report found that 75% of patients admitted for nonnicotine drug treatment were current cigarette smokers and that the underlying cause of death was tobacco-related or alcohol-related for 50.9% and 34.5% of the patients, respectively

(28). Additionally, psychiatrists are especially well-equipped to incorporate behavioral techniques, education, and prevention strategies to address tobacco addiction, which is the most common addiction and the addiction most likely to contribute to the deaths of their patients

(29). We found that psychiatrists were also less likely than other physicians to address preventive health measures such as poor nutrition, weight, and exercise habits.

Others have found that preventive practices are poorly established in office-based psychiatric practice

(30) and are often ignored

(31). The psychiatrists in this study were older than the other female physicians, and older age has been correlated with a lower likelihood of preventive health care counseling practices

(8). Psychiatrists in this study were more likely to be current or ex-smokers than nonpsychiatrist physicians; these personal habits may be correlated with psychiatrists’ lesser smoking counseling rates despite training equivalent to that of other physicians

(8). Historically, psychiatrists have held differing views on the seriousness of certain drug addictions such as marijuana abuse

(32) and on the philosophy of addiction as disease versus behavior

(33). This difference in viewpoints may be reflected in the overall lack of counseling about tobacco and alcohol abuse.

Despite their fewer work hours and greater likelihood to be solo practitioners, psychiatrists did not differ from the other female physicians in perceived work amount, work stress, work control, or career satisfaction. Psychiatrists may be less accepting than other doctors of occupational burdens. Alternatively, the practice of psychiatry can be isolating and has unique stressors involving great emotional and empathic requirements from the psychiatrist

(21). The majority of the emotional burden of psychiatric practice is faced alone in solo practice, and this may add to the perceived work stress.

Our findings are limited by the subject group studied (i.e., exclusively women), the self-reported nature of the data, and a 59% response rate. However, the few other large (N>500) studies of U.S. physicians (primarily or exclusively male) conducted in the past 20 years have used similar methods for determining eligibility and have reported similar response rates

(17).