With progression of HIV infection, there is a preferential decline among subsets of CD4 T cells; the naive CD4 T helper-inducer cell subset (CD4

+CD45RA

+) declines more than the memory subset (CD4

+CD29

+), resulting in disruptions in the cellular immune repertoire for novel antigens that underlie susceptibility to opportunistic pathogens

(1). Rising CD4

+ T cell counts following antiretroviral therapy are due primarily to the redistribution of memory CD4

+ T cells, with “reconstitution” of naive CD4

+ T cells being delayed for several months (2). Any increases in CD4

+CD45RA

+ cells may represent cells newly generated by the thymus (i.e., renewed thymopoiesis) or expansion of naive T cells from the periphery

(2). One can distinguish naive CD4

+ T cells that are newly differentiated from the thymus by enumerating “transitional” naive CD4 T cells—those that are actively converting from a CD45RA

+CD29–, or “virgin,” condition to a CD45RA–CD29

+ memory phenotype, since increases in CD45RA

+CD29

+ cells likely come from new naive cells

(3). HIV-positive persons may experience abnormal physiologic responses to stressors, which may contribute to immunologic deficits

(4). Stress management teaches people more efficient methods for coping with stressors and may affect components of the immune system

(5). This study tested the effects of stress management on CD4

+CD45RA

+CD29

+ cells over 6–12 months in HIV-positive gay men.

Method

HIV-infected gay or bisexual men between 18 and 55 years old with one or more non-AIDS-defining symptoms or a T-helper-inducer cell (CD3

+CD4

+) count of 200–700 cells/mm

3 who were fluent in English were recruited and signed an informed consent statement approved by our institutional review board. We excluded men with major psychiatric diagnoses (according to the nonpatient HIV version of the SCID

[6]), signs of gross neurocognitive dysfunction, or full-blown AIDS. For each man, 100 μl of heparinized whole blood was incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature with optimal concentrations of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies—CD45-FITC, CD14-RD1, CD8-FITC, CD4-RD1, CD56-RD1, CD4-ECD, CD29-FITC, CD45RA-RD1—and isotype control antibodies (Coulter, Hialeah, Fla.). After incubation, the samples were lysed and fixed with Q-Prep (Coulter) and analyzed on an Epics XL-MCL flow cytometer (Coulter) by collecting 2500 events in the lymphocyte region. All determinations were corrected for purity by dividing by the percentage of CD45

+CD14– events in the lymphocyte gate. The percentage of CD4

+CD45RA

+ CD29

+ cells was converted to an absolute count by multiplying by the lymphocyte count, which was measured before and after the 10-week intervention period and again 6–12 months later.

We collected spot urine samples at the physical examination to screen for (and exclude) any subjects testing positive for cocaine or morphine metabolites, according to On Track Test cups (Roche). Antiretroviral medication status was coded as 0 (none), 1 (antiretroviral monotherapy), or 2 (antiretroviral combination therapy). We determined HIV load in serum from blood samples drawn at study entry and after intervention by using the Quantiplex HIV-1 RNA 3.0 Assay (bDNA) (Chiron, Emeryville, Calif.), a signal amplification nucleic acid probe assay that uses a sandwich nucleic acid hybridization procedure (logarithm of viral copies per milliliter).

The participants randomly assigned to cognitive behavior stress management attended 10 weekly 135-minute sessions (45-minute relaxation component and 90-minute stress management component) and were instructed to practice relaxation exercises twice daily between sessions. The relaxation component included progressive muscle relaxation, autogenics, meditation, and breathing exercises

(7). The stress management component included cognitive restructuring, coping skills training, assertiveness training, anger management, and strategies for using social supports. The participants in the control condition completed a 10-week waiting period and underwent assessments identical to those received by the participants assigned to cognitive behavior stress management (and at equivalent time points). After the week 10 assessment, the control subjects were offered a 1-day stress management workshop summarizing the concepts presented in the cognitive behavior stress management sessions.

Results

Follow-up data on naive T cells were available for 25 men, 16 who received cognitive behavior stress management and nine control subjects. The men were randomly assigned to groups in a 2:1 ratio (two to cognitive behavior stress management for every one assigned to the control condition) to facilitate formation of the stress management groups at regular intervals. These men had a mean age of 36.64 years (SD=7.51) and were largely Caucasian (60%, N=15) or Hispanic (36%, N=9). The men had a mean CD3

+CD4

+ cell count of 489.36 cells/mm

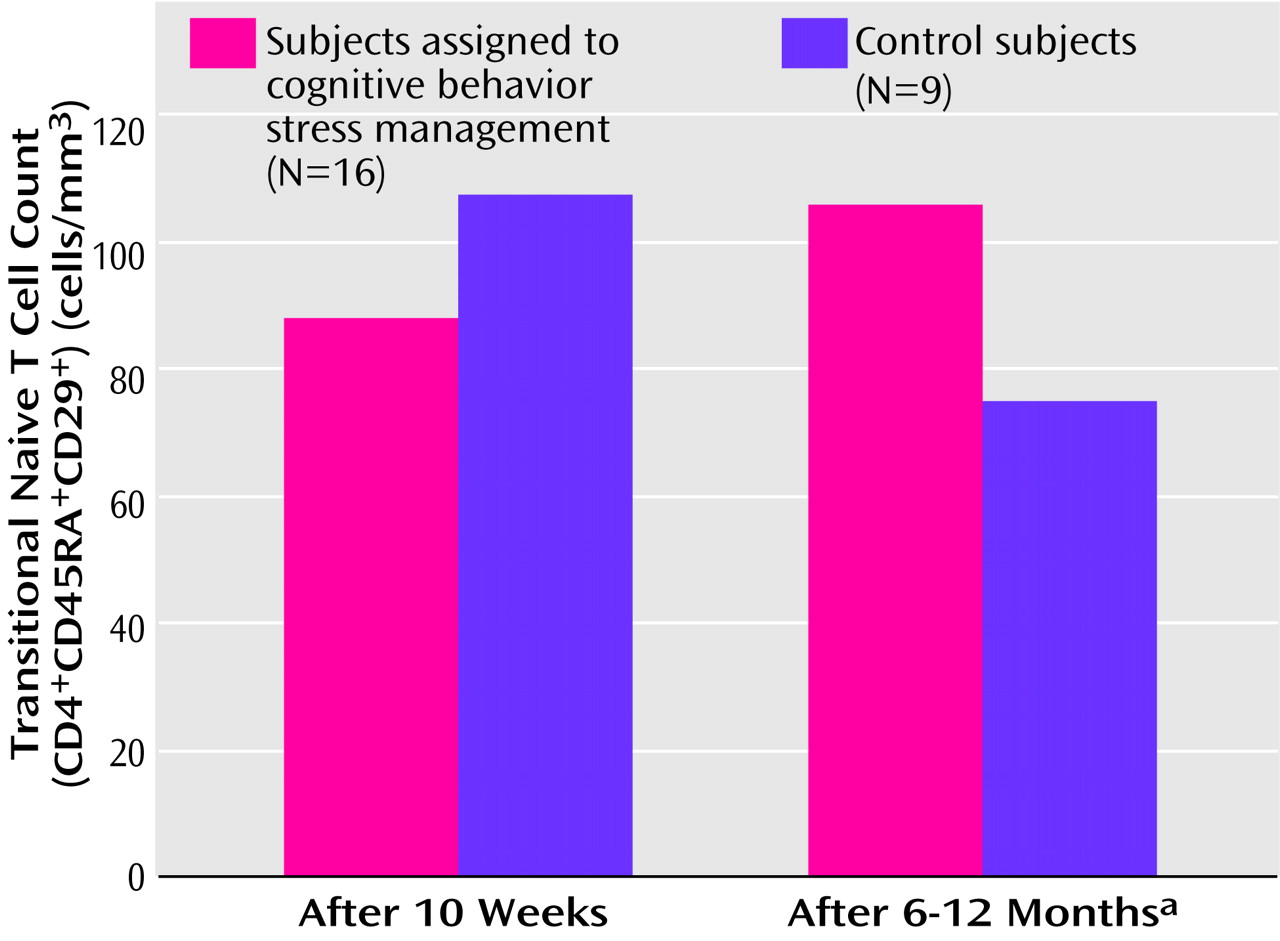

3 (SD=242.43) and averaged 2.08 (SD=1.45) HIV-related symptoms at study entry. There were no significant differences between the stress management and control groups on any medical, demographic, or biobehavioral variable at baseline or after the intervention, nor were there significant differences at baseline or postintervention between those who did and did not provide follow-up data on naive T cells. An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) controlling for postintervention levels of naive T cells revealed a significantly greater number of naive T cells at follow-up among the subjects who participated in cognitive behavior stress management than in those assigned to the control condition (

Figure 1). While the participants receiving stress management showed a small increase over this period, the control subjects showed more than a 25% decline (

Figure 1). At study entry there was no difference in HIV viral load between the stress management group (log mean=2.77, SD=0.70) and the control group (log mean=2.92, SD=0.89) (t=–1.14, df=18, p>0.25) and no difference in naive T cell count between the stress management group (mean=98.06, SD=109.00) and the control group (mean=88.44, SD=68.84) (t=0.24, df=23, p>0.80).

Discussion

HIV-positive men participating in a 10-week cognitive behavior stress management intervention showed greater signs of immune system reconstitution over a 6–12-month follow-up than did control subjects. These groups did not differ in HIV viral load or antiviral medications either before or after the intervention, suggesting that changes in immune system reconstitution over the subsequent year began from an even playing field of viral burden. Since HIV-infected persons are at heightened risk for significant pathophysiologic consequences from chronic stress and depressed mood, cognitive behavior stress management might influence immune status by reducing tension and by altering maladaptive appraisals of stressful events. Stress reduction appears related to the ability of the immune system to reconstitute naive T cells over time, possibly affecting cell-mediated immune responses to novel antigens and protecting against opportunistic infections. It remains premature, however, to conclude that cognitive behavior stress management offers clinical health benefits for HIV-infected persons. These findings may not apply to other HIV-infected groups (e.g., women), and since most of the men were not receiving combination therapy, it is unclear whether these results would generalize to HIV-positive persons currently on these regimens.