In previous studies of cancer patients, depression has been found to predict shorter survival

(1,

2) and active coping to predict longer survival

(3). However, other studies have not confirmed such associations. Thus, the evidence regarding this issue is still inconclusive

(4).

Method

The patients in this observational inception cohort study were recruited consecutively at the Thorax-Clinic Heidelberg-Rohrbach in Heidelberg, Germany, between June 1989 and December 1991. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Participants’ mean age was 59 years (SD=9; range=32–84), 83% were male, and 79% were married. In 84% the highest level of education was middle school.

Patients were selected to obtain equal numbers of patients with small-cell and non-small-cell tumors and to have sufficient power to control for cell type in the analyses. Histological classifications of the cases were as follows: small cell (N=48), squamous cell (N=30), adenocarcinoma (N=17), large cell (N=4), and mixed (N=4). One patient had stage I cancer, eight had stage II, 21 stage IIIa, 30 stage IIIb, and 43 stage IV. The patients later received chemotherapy (N=15), radiotherapy (N=14), a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy (N=44), or surgery (N=30). The patients’ mean score on the Karnofsky performance scale was 82 (SD=13, median=80). Physicians’ ratings of cancer severity on a 5-point Likert scale were also obtained.

Depressive coping and active coping were measured with the Freiburg Questionnaire on Coping With Illness by using both self-reports and interviewer ratings

(6). This questionnaire consists of 35 short statements about coping behaviors (such as “I am seeking information about illness and treatment”). Agreement with these items is rated on a 5-point Likert scale on which 1=not at all and 5=very much. The active coping scale consists of five items: seeking information about illness and treatment, undertaking problem-solving efforts, making plans of action and following them, intending to live more intensively, and deciding to fight against the illness (Cronbach’s alpha=0.64 for self-report, 0.74 for interviewer rating). Depressive coping is measured by five items: brooding, arguing with fate, pitying oneself, acting impatiently and taking it out on others, and withdrawing from other people (Cronbach’s alpha=0.68 for self-report, 0.69 for interviewer rating).

On the basis of patients’ answers in the interviews, the interviewers rated the same 35 items on a 5-point scale. The interviewer began the interview with the following request: “I would like you to tell me how your illness began.” After the patient had described the illness history, the issue of depressive coping was brought up in the following way: “Sometimes people feel depressed when they suffer from an illness like that. Do you know this sort of feeling yourself?” The interviewer sought further information for the interviewer ratings of coping with the following question: “What helps you to come to terms with your situation?” The interviews were tape-recorded. The interviewers were advanced medical and psychology students who had received extensive training and were supervised once a week. The interviewers were blind to the patients’ medical records. Interrater reliability was assessed with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) on the basis of 20 interviews that were rated by a second rater. The ICC was 0.76 for the depressive coping scale and 0.58 for the active coping scale. Disagreements between raters on this subset of 20 interviews were resolved by discussion.

The outcome variable was time from diagnosis to death. Follow-up assessments of survival times were performed in March 2001. By this time, 95 patients had died. Kaplan-Meier probabilities of survival were computed, with the continuous variables categorized at quartiles. Stage was split in the following manner: stages I, II, and IIIa versus stages IIIb and IV. Survival functions were compared by using the log-rank test for trend. In the multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model, all variables with p values <0.10 in the univariate analysis were included. The assumption of proportional hazards was checked by plotting the log-minus-log functions. Continuous prognostic factors were entered as continuous covariates into the Cox proportional hazards regression model

(7). The hazard ratio is the relative risk attributable to an increase by one unit in the level of a prognostic variable. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p<0.05 was considered significant. SPSS 10.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

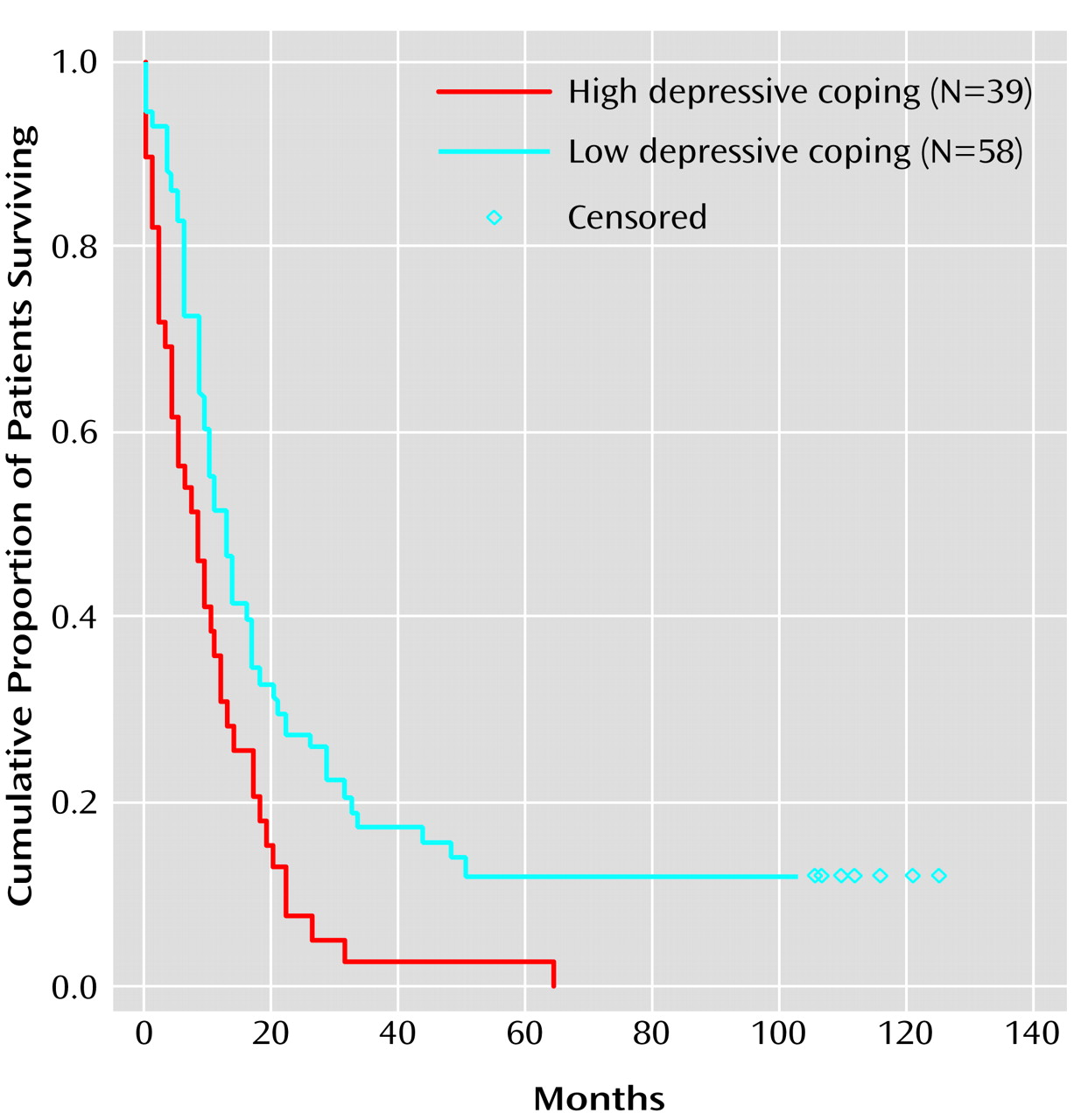

In the univariate analyses, both the self-report (χ2=4.86, df=1, p<0.03, log-rank test) and the interviewer ratings (χ2=6.87, df=1, p<0.02, log-rank test) of depressive coping were predictive of survival. The interviewer rating of active coping was not a significant predictor of survival, but it met the criterion for inclusion in the multivariate analysis (χ2=2.81, df=1, p=0.09, log-rank test). However, active coping showed no effect when assessed by self-reports (χ2=0.27, df=1, p=0.60, log-rank test). There were significant effects of tumor stage (χ2=8.57, df=1, p=0.003, log-rank test), Karnofsky performance scale score (χ2=22.59, df=1, p<0.001, log-rank test), and histological cell type, i.e., small-cell versus non-small-cell tumors (χ2=4.84, df=1, p<0.03, log-rank test). In addition, physicians’ ratings of the severity of the disease were predictive of shorter survival (χ2=5.87, df=1, p<0.02, log-rank test).

Since the self-report and the interviewer ratings of depressive coping were correlated (r=0.41, df=95, p<0.05), only the self-report was entered in the Cox regression analysis. However, active coping and depressive coping were not correlated and consequently were examined in the same equation. In the multivariate model (N=93, owing to missing values), both the self-report of depressive coping (Wald χ2=11.92, df=1, p=0.001, relative risk=1.91, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.32–2.77) and the interviewer rating of active coping (Wald χ2=4.46, df=1, p<0.04, relative risk=0.72, 95% CI=0.54–0.98) were independent predictors of survival time. In addition, tumor stage (stages IIIb and IV versus stages I, II, IIIa) (Wald χ2=6.00, df=1, p<0.02, relative risk=1.92, 95% CI=1.14–3.22) and Karnofsky performance scale score (Wald χ2=16.60, df=1, p<0.001, relative risk=0.96, 95% CI=0.95–0.98) were predictors of survival time. Cancer cell type (small-cell versus non-small-cell) was not a predictor of survival time (Wald χ2=1.49, df=1, p=0.22, relative risk=0.75, 95% CI=0.47–1.19).

The physicians’ rating of the severity of the disease was not entered into the Cox regression model during the first step because doing so would have unduly restricted the model’s statistical power (N=78). However, when included in the model, the physicians’ rating had no independent effect on survival, while the coping variables as well as the tumor stage and the Karnofsky performance status remained predictive. To examine the possibility that patients with a depressive coping style might receive a smaller amount of chemotherapy

(8), the number of chemotherapy cycles received by a subgroup of patients was included in the Cox regression model; yet again, the findings did not change substantially.

Figure 1 shows Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with low and high levels of depressive coping. The groups were selected on the basis of a median split of mean self-reported scores on the depressive coping items of the Freiburg Questionnaire on Coping With Illness. Median survival time was 14 months for patients with a low depressive coping score and 9 months for patients with a high depressive coping score.