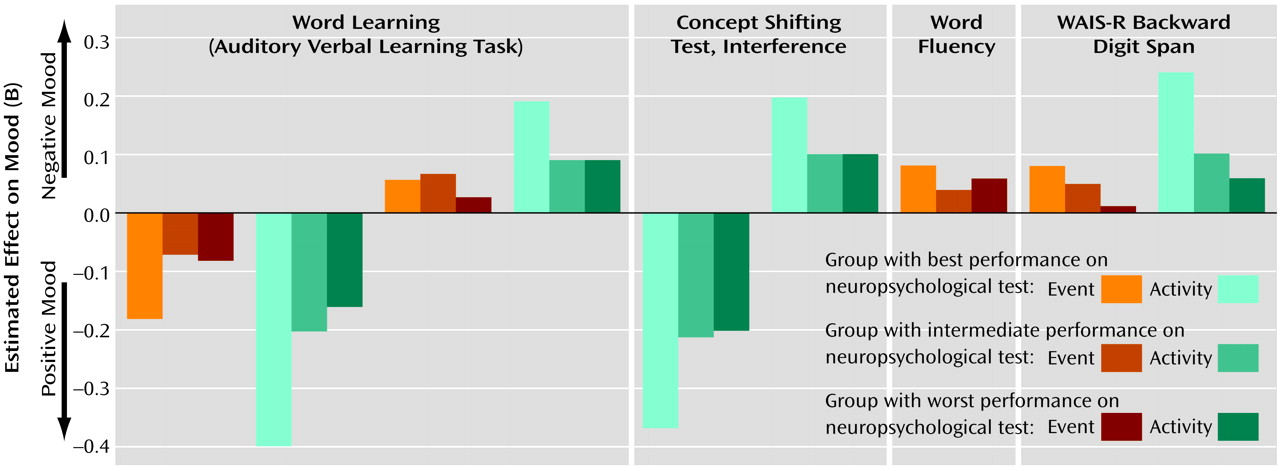

The present study showed that, in some instances, cognitive functioning did not alter the moment-to-moment emotional reaction to stress. In other instances, an inverse relationship was found, indicating that a better performance on the neuropsychological tests was related to more sensitivity to daily life stress. The present results therefore suggest that moment-to-moment sensitivity to stress may not be a consequence of cognitive impairments and that these mechanisms may act on different pathways that may even be mutually exclusive to a degree. There is evidence that both cognitive impairments and abnormal sensitivity to stress are also present in the first-degree relatives of patients, albeit to a lesser degree

(15,

34,

35). This, in combination with the current findings, may indicate that the two vulnerabilities are transmitted independently, and it is attractive to speculate that they represent the underlying mechanism of the extensive clinical heterogeneity in schizophrenia that many have suggested can be reduced to two main forms: an episodic, reactive, good-outcome form and a more chronic form characterized by high levels of negative symptoms and neurocognitive impairment

(18,

36–39). More research is necessary to clarify the association between these endophenotypes and symptom levels.

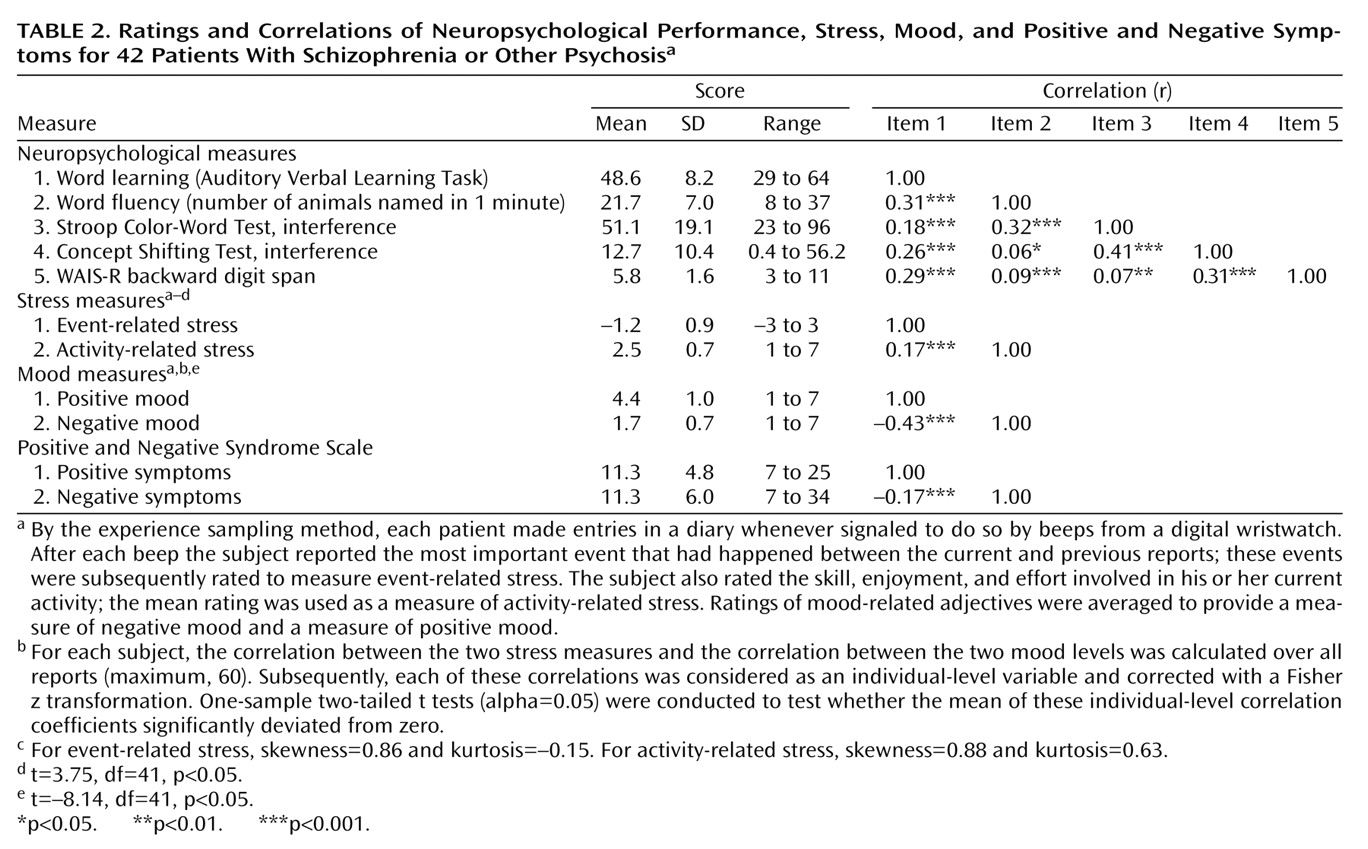

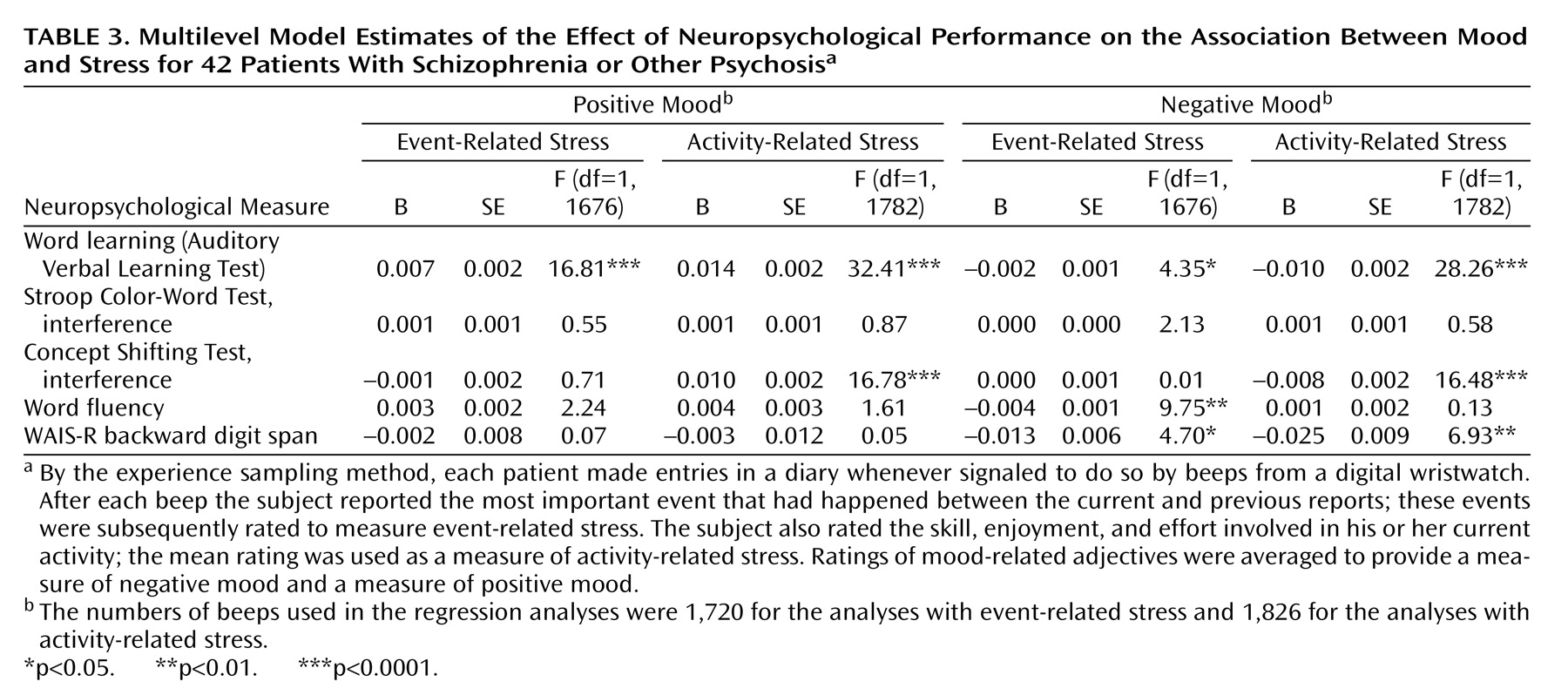

The differences in the statistical associations of the different stress measures and neurocognitive tests with mood (some associations did not reach significance while others did) are in all likelihood related to the fact that a variety of different variables are used to map neuropsychological functioning, which are all correlated with each other to a degree but also represent independent domains, with different sources of variability. Thus, some neurocognitive tests were more sensitive to differences in mood reactivity to certain stressful situations.

Alternative explanations for the reported results can be postulated. Sensitivity to stress is measured by means of self-report and, therefore, requires the capacity of introspection. First, neuropsychological deficits might impair the capacity to reflect on one’s own inner mood states. However, this seems unlikely given that no main effects on mood were found for neuropsychological functioning. It has also been reported that cognitive impairments are related to negative symptoms such as flat affect, which might reduce emotional responsiveness

(40). However, there is evidence that flat affect is more a dysfunction in

expression of emotions than in

experience of emotions

(30,

41). Previous research with the experience sampling method

(30) showed that patients who were blunted affectively reported the same intensity and fluctuation in positive and negative emotions as did patients without blunting. Second, a certain level of cognitive functioning might be necessary in order to experience the environment, for example stress, and report it. This hypothesis, however, again seems unlikely as subjective appraisals of stress were not associated with the neuropsychological test results. In comparisons of the cognitively best-performing group with the two other groups (intermediate and worst performance), no differences were found in mean, standard deviation, variance, and range of the subjective appraisal of both stress related to activities and stress related to events. Of course, the subjective appraisals of stress may be related to qualitatively different objective situations. For example, the patients with the best cognitive performance spent about 25% of their time in work-related activities, compared to only 6% in the two other groups. The latter, on the other hand, spent more time doing nothing (12% compared to 6% in the group with the best cognitive performance) and doing leisure activities (30% versus 22%). For the present analyses, however, the differences in objective situation do not matter, as the subjective appraisals of stress were used as the primary independent variable. Even if it were argued that work-related stress is different in nature from stress related to other activities, a post hoc exclusion of all work moments showed that this did not change the pattern of results. (In the reports made for all beeps, the estimated effects [Β] of activity-related stress were 0.16 [SE=0.02] for negative affect and –0.28 [SE=0.02] for positive affect. When work moments were excluded, the estimated effects were 0.17 [SE=0.02] for negative affect and –0.29 [SE=0.02] for positive affect.) Finally, the results could be explained by differences in coping. Lukoff and colleagues

(17) put forward the hypothesis that cognitive impairments play an intermediate role between environmental stress and genetic vulnerability, possibly by impairing the coping skills of a patient. The present results do not agree with that hypothesis, at least not as far as coping with events in the flow of daily life is concerned. Patients who are impaired neuropsychologically may display poorer cognitive coping strategies, but poorer coping strategies per se may not lead to increased emotional reaction and therefore greater sensitivity to stress. The advantage of the experience sampling method is that it confers ecological validity to measures of environmental stress.