Over the past decade, a growing body of work has provided compelling support for nonmotor functions of the cerebellum. Evidence for this derives in part from elegant neuroanatomic studies demonstrating multiple parallel loops between the cerebellum and diverse regions of the cerebral cortex, including nonmotor limbic and frontal areas

(1,

2), similar to the loops linking the basal ganglia to different regions of the cerebral cortex

(3). Other pathways of potential relevance include reciprocal connections between the cerebellum and brainstem catecholaminergic (locus ceruleus)

(4) and serotoninergic (dorsal raphe) nuclei

(5), the hypothalamus

(6), the brainstem reticular formation

(7), and the ventral tegmental dopaminergic neurons projecting to the forebrain

(8). These connections are of functional significance; investigations of normal human and nonhuman primate cerebellar function suggest a modulating role for the cerebellum in a variety of cognitive and emotional domains

(9,

10).

Consistent with the existence of nonmotor cerebellar functions, preliminary evidence points to cognitive and psychiatric disturbances in patients with diseases affecting the cerebellum. For instance, most—but not all—investigations have found that subjects with moderate degenerative cerebellar diseases develop mild subcortical dementia

(11,

12). Numerous case reports have suggested the presence of psychiatric disease in patients with cerebellar damage, including mania

(13,

14), “psychosis”

(15), and schizophrenia

(16). Skre

(17), examining subjects with any type of hereditary ataxia and using largely undefined and now obsolete psychiatric diagnostic schemes, found psychiatric disorders in approximately 23% of subjects, 12% of their neurologically normal family members, and 3% of the neurologically normal individuals from families without neurological disease. Elevated rates of short-lived mild depression have been detected acutely after cerebellar or brainstem strokes

(18). Schmahmann and Sherman

(19) examined 20 consecutive patients, primarily with cerebellar stroke, and described a “cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome” that involved executive, visuospatial, and linguistic dysfunction, accompanied by personality change.

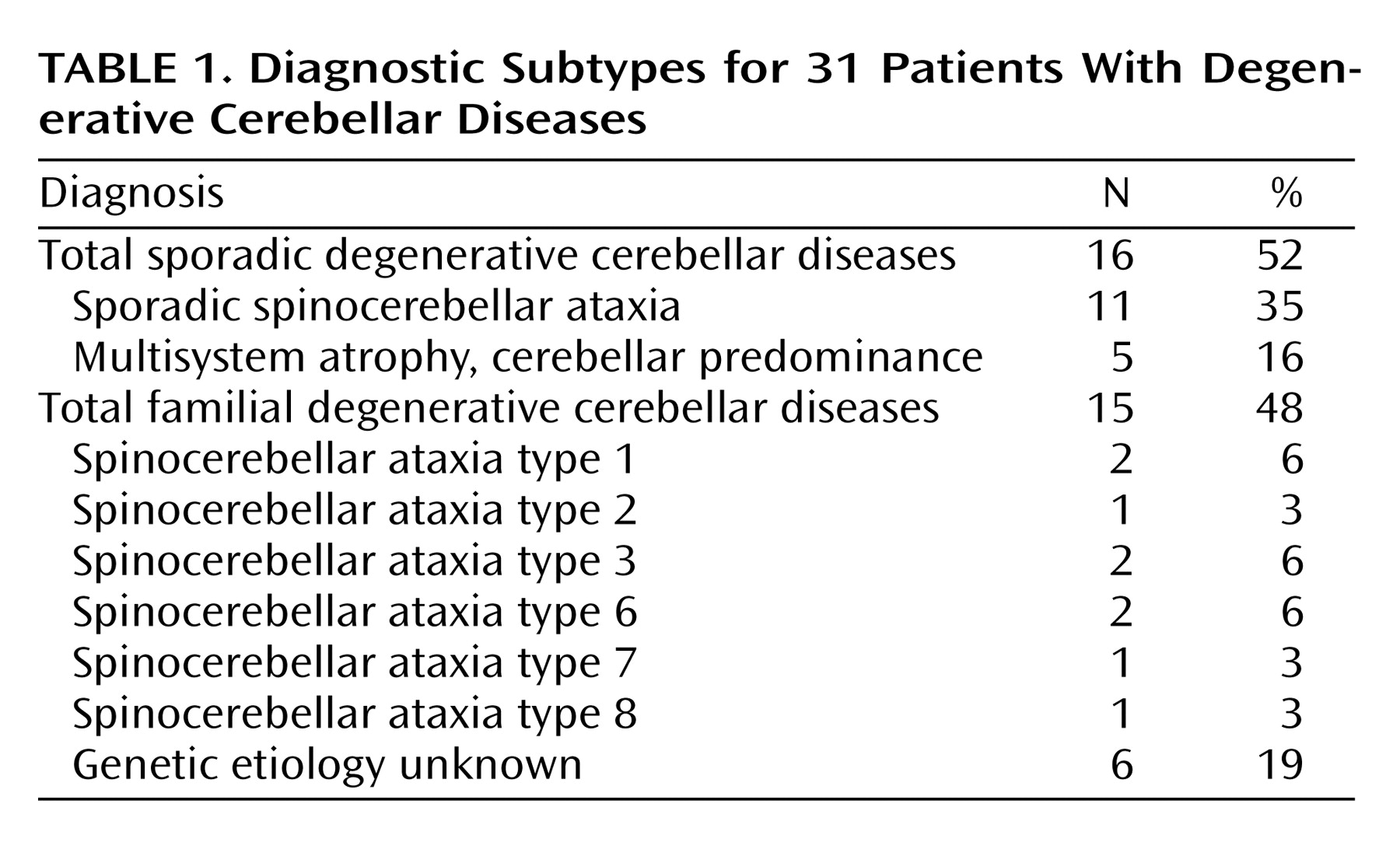

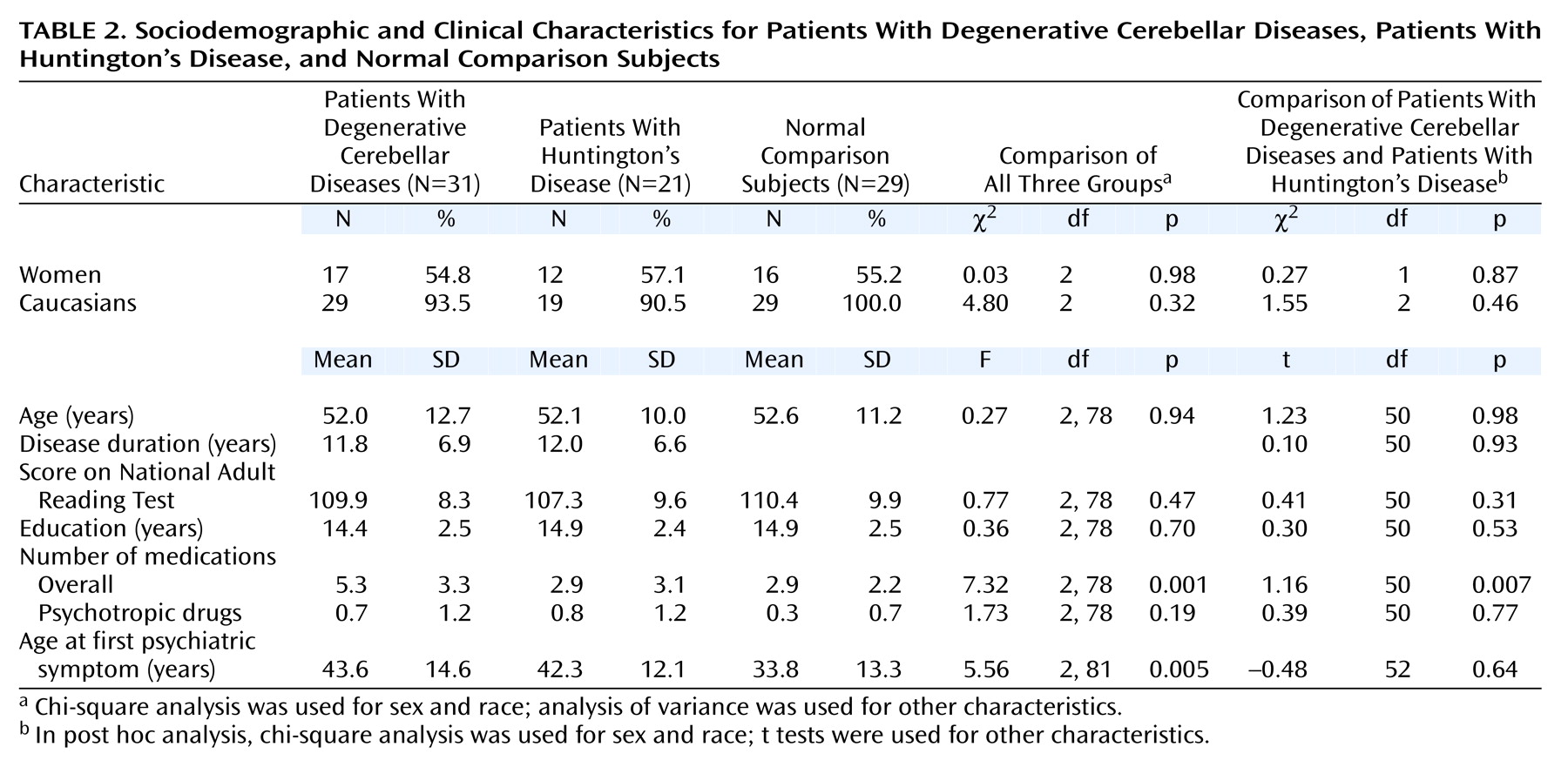

The present study was designed to address the issue of cognitive and noncognitive psychopathology in degenerative cerebellar diseases, using standardized methods of assessment and both neurologically impaired and neurologically healthy comparison groups. In an attempt to minimize diagnostic heterogeneity, we chose patients with degenerative cerebellar disease, either spinocerebellar ataxia or multisystem atrophy, adult-onset progressive disorders that affect the cerebellum

(21). Spinocerebellar ataxia is actually a large group of very similar hereditary and sporadic disorders (including so-called “pure cerebellar degeneration”) that are characterized by signs and symptoms of cerebellar dysfunction, frequently accompanied by evidence of involvement of other regions of the nervous system, and that are not secondary to other medical conditions such as stroke or cancer. The diagnosis of multisystem atrophy, usually considered a sporadic disorder, depends on evidence of combined involvement of the cerebellum, the basal ganglia, the pyramidal tracts, and the autonomic system—also unexplained by a medical condition. In practice, the phenotypes of spinocerebellar ataxia and multisystem atrophy overlap, and it is possible to select subjects with either diagnosis who have findings largely limited to the cerebellum.

Discussion

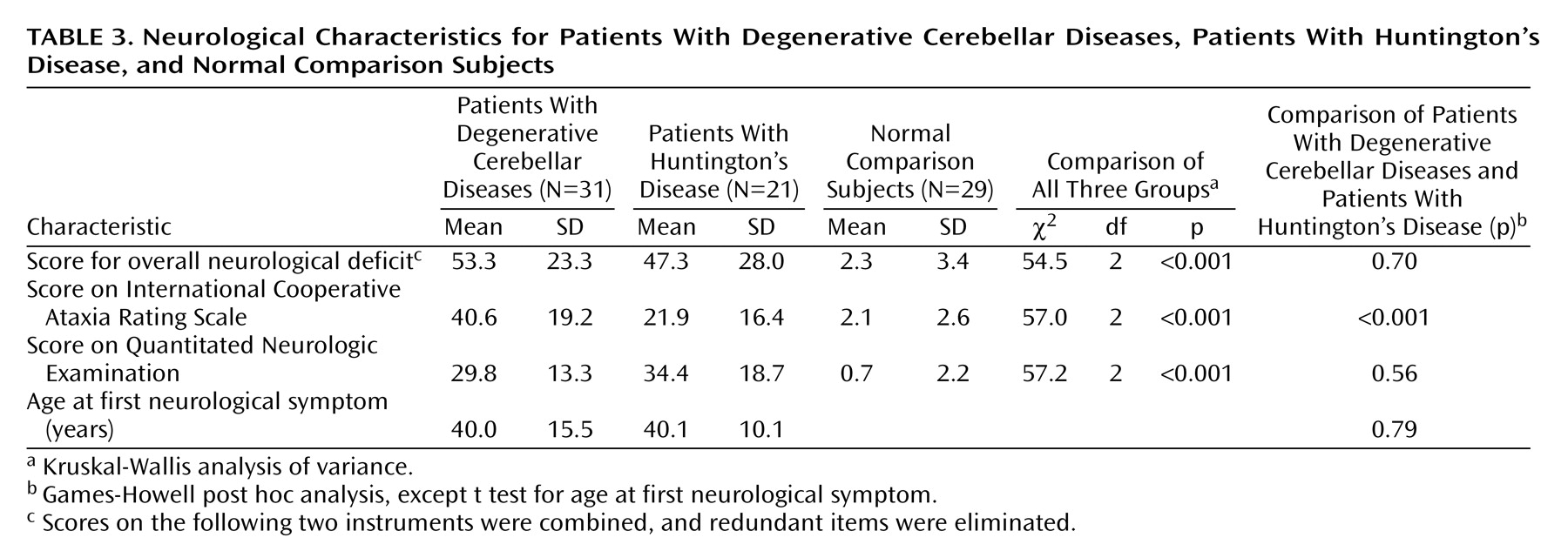

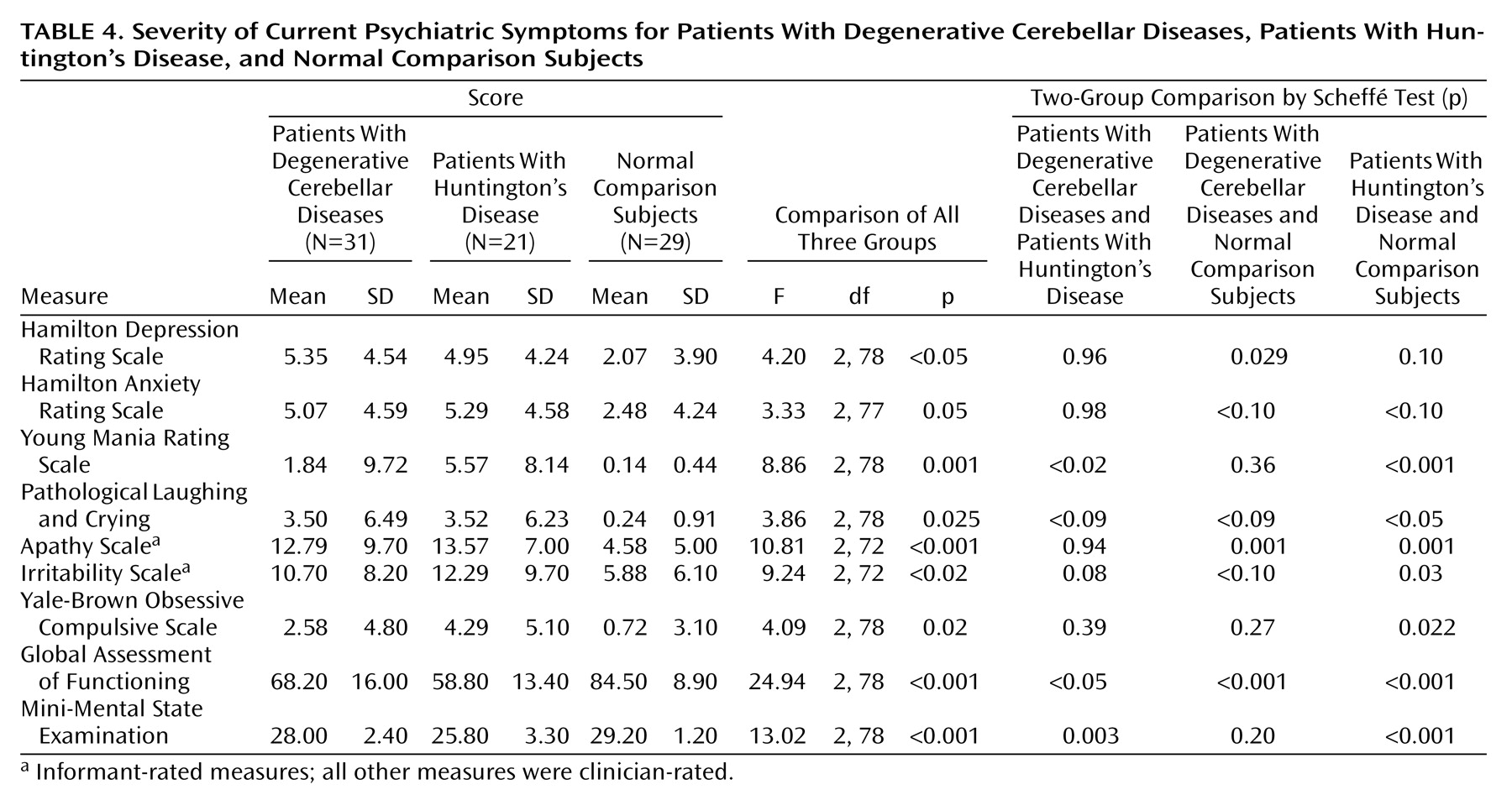

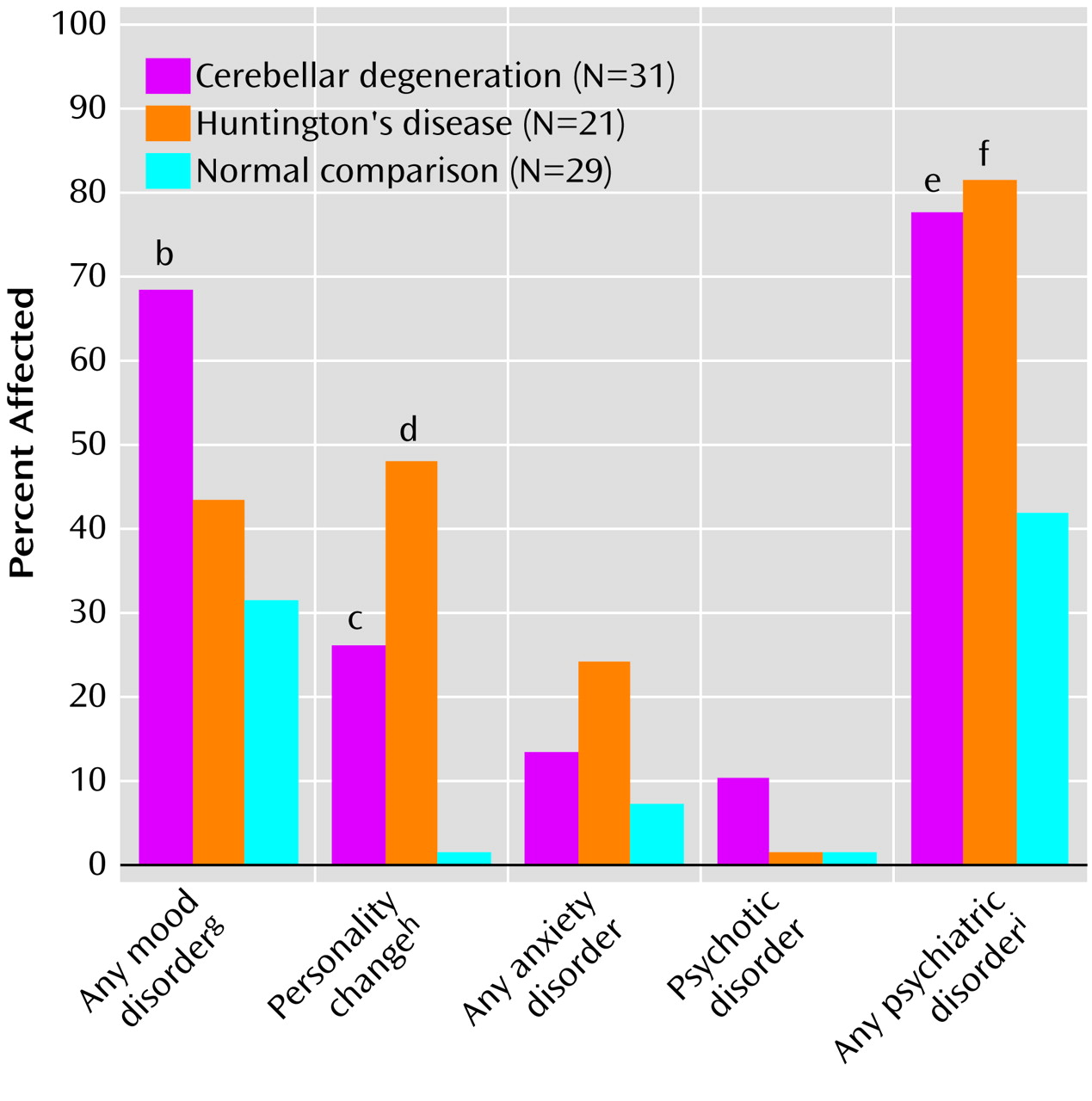

The primary result of this study was that psychiatric manifestations of degenerative cerebellar diseases were detectable in 77% of the subjects, similar to the rate observed in Huntington’s disease and significantly higher than the rate of psychiatric disorders seen in neurologically normal comparison subjects. The most common diagnoses in the patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases were depressive disorders, personality changes, and cognitive impairment. The rate of noncognitive psychopathology was higher than in our chart review study, while the rate of clinically important cognitive impairment was lower. The former difference is an expected consequence of the nature of the assessments in each study. The latter was somewhat surprising and may indicate that the criteria employed in the present analysis were more conservative than those applied during routine neurological examinations or showed a difference in subject ascertainment between the two studies. The comparable overall rates of noncognitive psychopathology in the patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases and the patients with Huntington’s disease were also somewhat surprising. However, the overall rates did not provide a complete picture, since the Huntington’s disease patients tended to have more severe manifestations of the disorders and the rate of cognitive impairment was substantially higher in the patients with Huntington’s disease.

Although a history of mood disorders was common in the patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases, our cross-sectional evaluation indicated that few patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases were depressed at the time of the evaluation, similar to the findings of Kish et al.

(12). The low rate of cross-sectional depression confirms the importance of a longitudinal psychiatric history in assessing psychopathology in patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases and implies that degenerative cerebellar diseases predispose to intermittent rather than chronic mood disorders. Bipolar disorder or mania was not seen in our degenerative cerebellar diseases group, in contrast to the “incidental observations” of Kish et al.

(12) that 14% of the patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases were “mildly euphoric” and 12% were “impulsive,” and the report of Lauterbach

(13) that 20% of subjects with focal cerebellar circuit lesions developed bipolar disorders. These differences likely derive from variability in patient populations and diagnostic protocols and the relatively small size of all samples.

Personality change was a frequent diagnosis in both patients with Huntington’s disease and patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases. These changes were difficult to detect with rating scales but did emerge on careful clinical evaluation. A total of 50% of the patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases and 20% of the patients with Huntington’s disease with personality change did not meet the criteria for cognitive impairment or dementia, suggesting that personality changes may be an independent manifestation of neurodegeneration rather than a nonspecific aspect of a dementing process. The personality changes in our subjects were similar to the affective component of the cognitive affective syndrome described by Schmahmann and Sherman

(19). However, the design of our study enabled us to demonstrate that degenerative cerebellar diseases predispose patients to a variety of psychiatric disorders rather than a single affective syndrome. The extent to which these disorders are also present in patients with focal cerebellar lesions, such as strokes, remains to be determined.

Our method for determining personality change was based on a DSM-IV-based interview, an informant history of personality change, and cross-sectional informant rating scales of irritability and apathy. Other investigators have applied standardized quantitative rating scales of personality dimensions, such as the Neuroticism-Extroversion-Openness Personality Inventory, to Alzheimer’s disease and other neuropsychiatric disorders

(35–

37), with informants providing separate ratings of premorbid and current personality. The reliability of the Neuroticism-Extroversion-Openness Personality Inventory to detect personality change in Alzheimer’s disease has been preliminarily established

(38,

39). However, the extent to which the personality dimensions assessed in the Neuroticism-Extroversion-Openness Personality Inventory correlate with syndromes typically associated with neuropsychiatric disorders (e.g., apathy, irritability, and agitation) remains to be fully established. Other standardized assessments have attempted to directly approach personality variables in neuropsychiatric patients from a categorical (syndromic) perspective

(40–

42); the reliability of these instruments in detecting personality change, particularly in patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases, is not known. It is possible that use of one or more of these more fully operationalized diagnostic procedures in our study, whether dimensional or categorical, may have yielded different findings concerning personality change in patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases and Huntington’s disease. More generally, however, the analysis and validation of personality change in neuropsychiatric conditions are clearly in a nascent stage. The vagueness of the DSM-IV personality change diagnosis (“personality change due to a general medical condition,” 310.1), the unclear relationship between personality change and cognitive impairment, and, most significant, conceptual uncertainty regarding classification and description of personality change

(36) create limitations in interpreting the current data.

One case of schizophrenia and two cases of psychotic disorder not otherwise specified were detected in the group with degenerative cerebellar diseases but none in either of the two other groups. The presence of these syndromes in 10% of our subjects is high enough to suggest that cerebellar degeneration may increase the risk for psychotic phenomena, consistent with the concept of “cognitive dysmetria” proposed by Schmahmann

(43) and applied to schizophrenia by Andreasen and colleagues

(44). The essence of this hypothesis is that the fluidity and synchrony of thought, like movement, are normally modulated by the cerebellum. Hence, if circuits between the cerebellum and cerebral cortex develop abnormally or suffer damage, the result may be misperception and cognitive dysfunction. In support of this hypothesis, anatomical and functional neuroimaging studies have suggested cerebellar involvement in idiopathic schizophrenia and affective disorder, although the evidence remains controversial

(44–

46).

Almost 20% of the patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases and over 70% of the patients with Huntington’s disease had functionally significant cognitive disorders. It is unlikely that the cognitive impairment that we observed can be completely explained by high rates of depression, since cross-sectional ratings of depression in our subjects were relatively low at the time of the assessment. These clinical results are consistent with our preliminary analysis of a detailed neuropsychological evaluation of the same subjects (unpublished data of Brandt et al.). Subjects with degenerative cerebellar diseases appear most impaired in executive function and least impaired in memory, whereas the greatest impairments in the subjects with Huntington’s disease were in measures of spatial ability and memory. Our preliminary chart review suggestion of a 30% rate of cognitive impairment in subjects with degenerative cerebellar diseases was higher than the results of the current study or of previous reports, reflecting a difference in the study methods or subject population.

The extent to which the psychopathology of degenerative cerebellar diseases reflects a primary manifestation of neuropathology, as opposed to a secondary and nonspecific manifestation of the demoralization of chronic illness, is a critical issue. The lower rates of psychopathology in the group of neurologically normal comparison subjects, chosen because of their exposure to the psychological stress of chronic illness in their role as caregivers and family members, provide evidence that the psychopathology of degenerative cerebellar diseases is directly linked to brain pathology. This link is also supported by the syndromic nature of the psychiatric disorders detected in patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases and particularly the presence of personality changes and psychotic disorders. In addition, although Huntington’s disease and degenerative cerebellar diseases groups both exhibited the features typical of subcortical dementia, the cognitive and psychopathological manifestations of the two diseases were not identical. Since the illness duration and motor impairment in each group were similar, this phenomenological difference appears to reflect the underlying neuropathology of each disease. Recent work has established that the regions of the cerebral cortex in direct communication with the cerebellum only partially overlap with these regions communicating with the basal ganglia. For instance, projections to prefrontal area 12, roughly corresponding to the orbital cortex, have been detected from the basal ganglia but not from the cerebellothalamic system

(3). Alternatively, differences in psychopathology may be a consequence of the different modes of information processing in the basal ganglia and cerebellum, an attractive hypothesis given the unique modular nature of cerebellar microcircuitry

(47).

Aside from concerns regarding the diagnosis and interpretation of personality change, other important limitations of this study include the modest group size, the cross-sectional design, the inherent subjectivity of psychiatric diagnoses, and the heterogeneity of the group with degenerative cerebellar diseases. The etiology of the degenerative cerebellar diseases was variable, and in many subjects, neuropathology may have extended beyond the confines of the cerebellum, although predominant cerebellar findings were the basis for subject selection. While noncerebellar neuropathology increases the difficulty of interpreting the specific role of the cerebellum in our findings, a strength of the study group was that it more closely resembled the population of patients with degenerative cerebellar disease that are seen for clinical care than a group with disease limited to the cerebellum.

In summary, we reported high rates of psychiatric disorders and clinically detectable cognitive impairment in 31 subjects with degenerative cerebellar diseases. Within the limitations of the study design, the results support a role for the cerebellum in the modulation of cognition and emotion. From a clinical perspective, our findings suggest that patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases should be carefully evaluated for the presence of psychiatric disorders and cognitive impairments. Although the underlying neurodegeneration in degenerative cerebellar diseases may not yet be treatable, management of the accompanying psychiatric disorders and cognitive impairment with a combination of education, pharmacotherapy, and supportive psychotherapy may have a major impact on quality of life for patients and their families.